[Image by Gerd Altmann under Creative Commons]

India ranks No. 45 (out of 50 countries) on the Bloomberg Innovation Index announced last month. India figures worse than Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and a host of other countries. Should we be worried about this?

Let’s begin by understanding why we are placed so low.

Measuring innovation is a tricky business and depends, to start with, on how you define innovation.

The Bloomberg Index adopts a broad definition—“the creation of the products and services that make life better”—but then goes on to take an R&D and technology-centric view of innovation rather than a market-centric or contextual view. The seven equally-weighted metrics in the Bloomberg Index include R&D intensity, high-tech company density and patent activity, all of which favour countries with a strong, high-technology-based manufacturing industry. Other metrics such as manufacturing value-added (MVA), productivity and research staff concentration are all on a per capita basis and therefore loaded against a country such as ours with a large population. The last metric, tertiary efficiency, measures enrolment in tertiary education and is linked to the Gross Enrolment Ratio, a metric on which we again perform poorly though this has been improving gradually in recent years.

Overall, given the structure of the Indian economy, particularly the relatively small proportion of manufacturing in GDP, and the fact that we have a fledgling presence in high-technology manufacturing (electronics), it is not surprising that India does not figure high on the Bloomberg Index.

And, India’s position on this index may not change dramatically any time soon. The current government’s flagship programmes such as Make in India and Start Up India are likely to have a positive impact on only two of the components of the Bloomberg index—MVA and high-tech density. Progress on the former will be intricately linked to what kind of manufacturing we pursue. If we concentrate on labour-intensive manufacturing, which tends to be at the low end of MVA, our rank will not improve substantially on this parameter.

This naturally prompts a bigger question: if this is not the right index, how should we measure innovation in India?

Many of the countries in the Bloomberg Innovation Index solved the problems of meeting basic needs decades ago. In these countries, innovation is all about meeting needs that users have not even imagined, a la Steve Jobs and Apple. But in a country with the largest number of poor and under-nourished people on the planet, what kind of innovation matters, and how should we measure it?

There is an urgent need to measure and track whether we are harnessing our creative potential to solve the important problems in education, health and agriculture that confront the country. We need to ensure that our ability to use knowledge to solve the core challenges of our country is being continuously enhanced. Even if we don’t compare ourselves with others, it would help if we could track our own innovation efforts in this direction, year on year.

Aravind Eye Hospitals improved the efficiency of doctors in doing cataract surgeries by a factor of 4 or 5. Narayana Health does bypass surgeries at 40% the cost of large hospitals in India and one-tenth the cost of a bypass surgery in the US. India’s Jaipur Foot offers prosthetic limbs customised to the individual and the Indian environment for one-hundredth the cost of prosthetics abroad. But the Bloomberg Innovation Index does not really capture important success stories such as these which have the potential to transform Indian healthcare.

In short, the driving force for innovation in India is improving accessibility and affordability. But, both the WIPO-Insead Global Innovation Index and Bloomberg don’t capture these dimensions well.

There are two other dimensions that need to be captured when we measure innovation in India. One is inclusivity, and the other is sustainability.

Inclusivity is important because an individual who faces a problem would be the most motivated to find a solution. A higher degree of inclusivity also leads to a larger number of innovators across the country, thereby leading to a more creative society. The grass root innovation movement in India has done much to involve hundreds if not thousands of people in the innovation process.

Some of the most challenging needs for innovation arise out of sustainability concerns. While high-tech solutions to environmental challenges come from the West, local knowledge offers sustainable solutions which are much less energy intensive. Currently used indices don’t capture these contributions either.

Amid all the excitement about startups, the types of startups being launched and what problems they solve is important. It is debatable whether yet another startup to order food is an important addition to our country, let alone to India’s innovation capacity.

Innovations benefit the country only when they are commercialised and widely used. In fact, it’s worth remembering that commercialisation and adoption are what differentiates innovation from invention. While the development of new high-yield varieties of wheat and rice was important, the success of India’s Green Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s lay in the adoption of these varieties across important agricultural states of our country. Organisational changes that enhanced extension work were critical to this process.

Commercialisation has been the Achilles’ heel of Indian innovation for decades. All attempts to measure innovation progress in India must capture whether we are getting better at commercialisation.

Such adoption and diffusion has played a critical role in other success stories. Software services is a case in point. Improved software development, project management and quality assurance processes diffused widely across the industry, and got reflected in the large number of CMM (Capability Maturity Model) level 5 companies, the largest in the world.

The quality of Intellectual Property (IP) protection and enforceability is usually considered to be critical to create a positive climate for innovation. After all, why would anyone innovate if someone else who has not made any effort could just copy the former and prevail in the market? Another recent report— the Global IP Index launched by the US Chamber of Commerce's Global Intellectual Property Centre—suggests that India offers the least supportive environment for IP protection among 30 countries. But this flies in the face of strong evidence that we have strengthened our IP laws and made them more consistent with laws elsewhere in the world. Even enforcement has improved, though obviously we could do much better on this score.

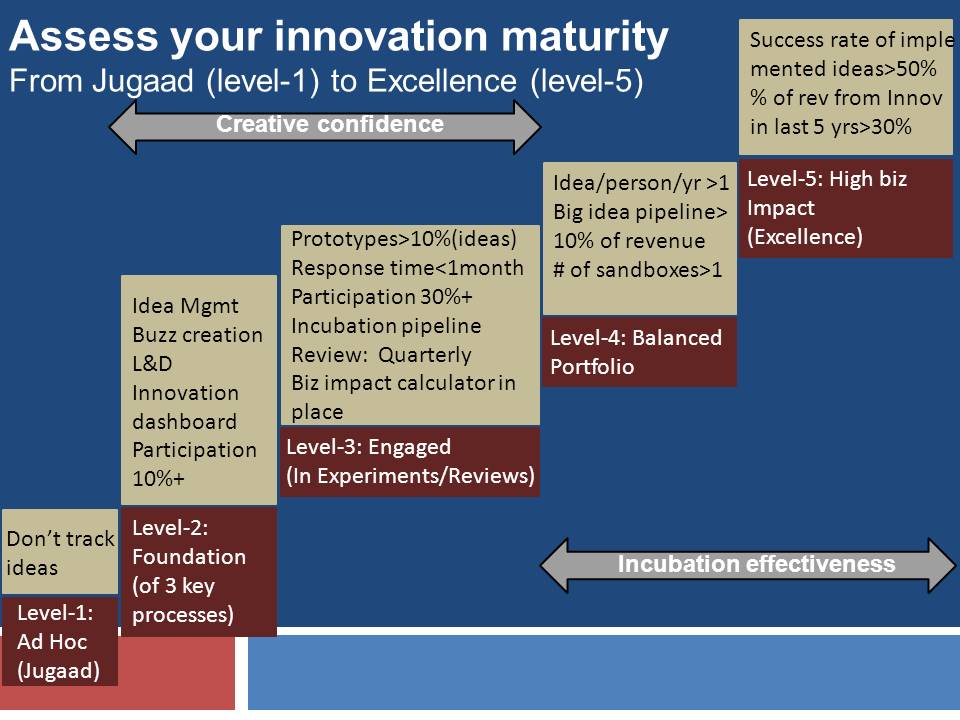

The quantum of innovation from a country or region depends on the capacity of firms to innovate—do they have the structures and processes, and the leadership required to innovate on a continuing basis? As a follow-up to our book 8 Steps to Innovation: Going from Jugaad to Excellence, Vinay Dabholkar and I developed a 5-level innovation maturity index (see graphic below). We found that most Indian organisations are stuck at level 2 or level 3 of this index. Tracking the progression of Indian firms in putting in place the right innovation processes would be helpful to know how India is progressing.

[ 5-level innovation maturity index ]

[ 5-level innovation maturity index ]

In short, we need to change the way we measure the innovation performance of countries or regions if we want to figure out how India is progressing on innovation. Our poor performance on existing indices may not be a cause for concern in itself, but should act as a trigger for us to develop the right metrics and monitor them on a continuing basis.