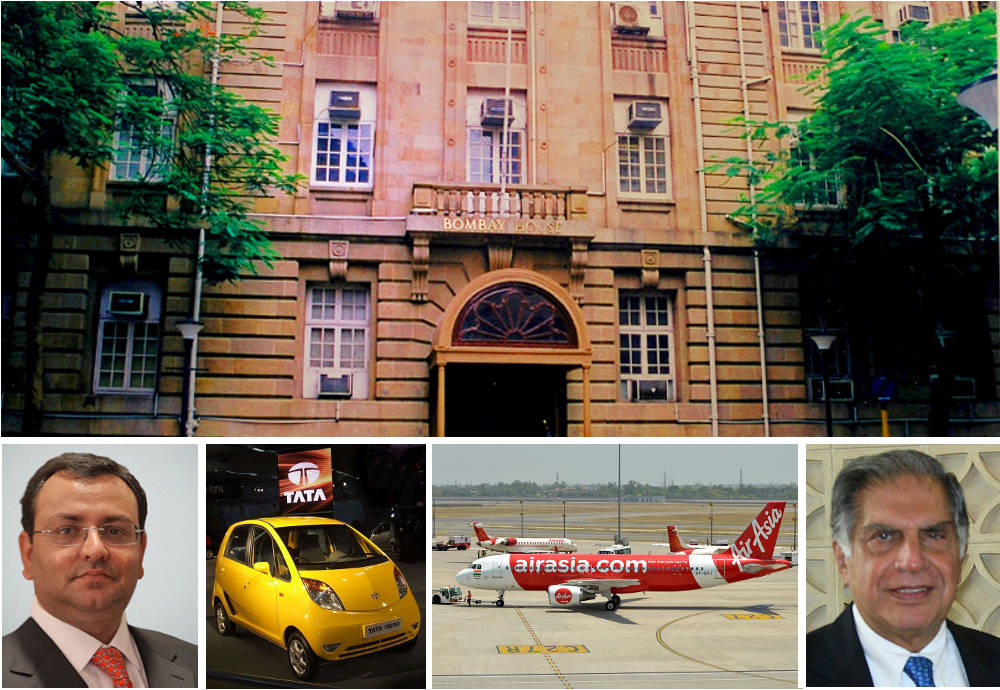

[Cyrus Mistry's unceremonious dismissal as Tata group chairman raises several questions. And the Tatas will have to answer them. Clockwise from top: Bombay House, the headquarters of the Tata group; Ratan Tata; Air Asia and Nano—two high-profile projects that Mistry has raised questions about; Cyrus Mistry. Bombay House's photograph by Arunthomasvtt via Wikimedia Commons. Tata Nano by Arulnathan under CC. Air Asia VT-APJ by Arjun Sarup under CC ]

Cyrus Mistry’s recent letter to the Tata Sons board and the trustees of the Tata Trusts is devastating for any corporate watcher.

If the assumption was that Mistry would quietly resign and move on, that has completely boomeranged. And how. The entire cast of characters: the directors at Tata Sons, the trustees at Tata Trusts, the boards of some of the publicly listed Tata companies, and Ratan Tata himself, will have a lot of questions to answer for from shareholders, employees, analysts and regulators.

Till date, not a single credible reason has been put up by the august Tata Sons board for dismissing Mistry as chairman. Except for some rumblings on television about unnecessary divestments from a battery of celebrity lawyers, a particular lobbyist of dubious reputation and some ham-handed attempts to plant stories in media.

Instead, Mistry’s riposte is direct, clinical and seems factual, for most part. And thanks to social media, it has been more widely read than any legal route would have managed to achieve. Within no time, the Tatas have responded to the letter being leaked to the world. But their response lacks substance and does little to shed light on the reasons behind the coup. It is clear that we haven’t heard the end of this saga. Whichever way this goes, be rest assured that the institutional damage to the Tata group will be incalculable.

There are a number of pertinent questions that this sordid Tata-Mistry saga raises.

1. What was the evidence of wrong-doing and poor performance that was placed before the board to demand Mistry’s ouster? Was it tabled, discussed and minuted, as part of due process? Especially, when the nomination and remuneration committee at the board is said to have lauded his contribution a few weeks ago. (And it is pertinent to note that Ishaat Hussain, a stalwart in the group and group CFO for many years, chose to abstain from voting on the resolution to remove Mistry.)

2. Even if there was clear evidence to suggest that he resign, why was this additional item sneaked into the agenda and not shared in advance with Mistry, given that he was to chair the meeting? Such subterfuge merely raises suspicion and does little to inspire confidence that the spirit of the governance process was followed, especially at the highest echelons of the Tata group.

3. Mistry has raised some serious ethical questions about two high-profile projects, where he was given no option but to fall in line: the aviation JVs with Air Asia and Singapore Airlines and the Nano small car project. And he has suggested that Tata had his own personal business interests tied to the continuance of the Nano project. If this is true, has this potential conflict of interest ever been clearly disclosed to shareholders? And was there enough of a business plan, beyond mere hubris, to open up a new frontier in the aviation business? If the chairman himself wasn’t convinced about the feasibility of the plan—but forced to accept it as a fait accompli—does it not amount to a clear subversion of the governance process?

4. In the same aviation transactions, there have been questions of impropriety raised about certain fraudulent transactions conducted between non-existent persons in India and Singapore worth nearly Rs 22 crore. What is the current status of the investigation following the first information report on those transactions? Why was the managing trustee Mr Venkatraman trying to paper over them?

5. Equally, there are some very serious allegations of dodgy accounting practices at Tata Motors Finance and off-balance sheet transactions at Indian Hotels, which need closer examination. How were such practices allowed to go through by the boards of publicly listed companies? What safeguards are now in place to ensure that these kind of practices don’t impair the financial health of these publicly listed firms?

6. Most of all, Mistry’s core argument that his restructuring plans were thwarted at every opportunity is pretty disturbing. If the majority shareholder, in this case the Tata Trusts, ended up cramping the functioning of the group chairman, how will the interests of minority shareholders be protected in such a case?

7. None of these issues ought to have flared out of control in this manner, if the two key protagonists, namely Tata and Mistry, had maintained a clear line of communication between them. Why were things allowed to deteriorate to such an extent thereby causing great damage to the institution? Why was the chairman not allowed the operating freedom to pursue his agenda?

There will be more prickly questions that will invariably pop up. It will be a messy boardroom battle, the likes of which we have perhaps never seen before. A lot more dirty linen could get aired in the days and weeks to come, before any kind of cleansing process can begin.

In the middle of this brouhaha, a seasoned business leader raised a valid question in a conversation over SMS: couldn’t Mistry have walked out with a handshake, a smile and silence? His point: when have such fights has ever served a purpose anywhere? Never overstay the welcome. After all, it only makes for entertainment for onlookers and damages the enterprise you called your nation, your cause, your purpose, until the last press meet or the town hall.

I respect that sentiment, except that I have a different point of view. Therefore, my response was simple: at least we now know what was really going on inside. Or else, none of this would have ever come out. After all, isn’t sunshine the best disinfectant? At least, this way we wouldn’t continue to live in our mythical world, where we treat our revered business leaders as royalty. Because all that ignoring it does is push the real truth under the carpet for a wee bit longer.

Let’s face it: Mistry fought back because he could. He perhaps had the courage of conviction that most CEOs, who are muscled out on the back of trumped up charges, lack. So let’s treat him as a whistle-blower and an activist. And an insider, to boot. And that is a rare combination.

Now, if there is one larger point that is worth mulling over, it is this: we as Indians, seem to place more trust on individuals, rather than commit ourselves to building stronger institutions. Be it in business, sport or politics, we raise our leaders to the level of a superhero and end up deifying them, instead of strengthening the governance of our institutions and the rules by which they ought to be managed. And time and again, when these very same leaders appear to have feet of clay, we cry foul, almost as if we have been deeply let down. It is about time that we wake up—and smell the Tata coffee.

(A shorter version of this column first appeared in Business Standard)