[Cadaverexquisito, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Good morning,

Earlier this week, we sat down to read the transcript of a talk delivered earlier this year by Daniel C Dennett, one of our favourite thinkers. He was speaking at the American Philosophical Association. His talk was fascinating and we latched on to every word.

“Consider a boulder dislodged by an earthquake rolling down a mountain. Bump, bump, bump. Its path is determined by the laws of physics, but it is not under the control of anything. It is out of control. Its trajectory is determined, but not controlled. Compare the boulder to an expert skier, hurtling down the mountain. The skier’s trajectory is also determined by the laws of physics, but the skier is in control, her trajectory determined by her decisions, mediated by her skill and strength, and the existing conditions of the snow, the wind, the conditions of her skis, and so forth. The skier might lose control and then become more like the boulder, still determined but now out of control. And if she then somehow managed to regain control, she would then be profoundly different from the boulder, being self-controlled again. All of these paths are determined, let’s agree; what happens is always the effect of the many causes at play…”

“Causation and control are not the same thing. Not all things that are caused are controlled. Things that are controlled are caused, like everything else, but control requires a controller, an agent of sorts designed to control a process, and that requires feedback: information about the trajectory and conditions that can be used by the controller to modulate the action. This is a fundamental point of control theory.

“Think about firing a rifle bullet. You’re controlling the direction of the gun barrel and, with the trigger, the time of the bullet emerging from the gun barrel. Are you controlling the course of the bullet after that? No. Where it goes after it leaves the muzzle is out of your control. Now, if you’re a really good shot, you may be able to calculate in advance the windage and so forth and you may be able to get it in the bull’s eye almost every time. But you are unable to affect the trajectory of the bullet after it leaves the gun. So it is not a controlled trajectory, it is a ballistic trajectory. It goes where it goes and, if your eyes were good enough to watch it and see that it was going ‘off course,’ you’d have feedback, but you wouldn’t be able to do anything about it… You fired the gun. You caused that bullet to go where it went, but you did not control the bullet after it left the gun.”

Dennett then goes on to compare the gun to a guided missile that can be controlled remotely and makes the point that “Remote control is real, and readily distinguished from out of control.” Having said that, he embeds a thought. “Autonomy is non-remote control, local or internal control, and it is just as real, and even more important.”

This provocative talk is worth every minute of time invested in. And the link is here.

In this issue

- Maradona and monetary policy

- Free speech with boundaries

- Brace yourself for 2021

Have a great day!

Maradona and monetary policy

Of all the tributes we read about Diego Maradona, we found this one in FT most interesting. It comes from Mervyn King, British economist and former governor of the Bank of England, who in 2005 drew parallels between Maradona’s goal against England in the 1986 football World Cup quarter-final and how monetary policy works.

“Maradona ran 60 yards from inside his own half beating five players before placing the ball in the English goal. The truly remarkable thing, however, is that Maradona ran virtually in a straight line. How can you beat five players by running in a straight line? The answer is that the English defenders reacted to what they expected Maradona to do. Because they expected Maradona to move either left or right, he was able to go straight on.

“Monetary policy works in a similar way. Market interest rates react to what the central bank is expected to do. In recent years the Bank of England and other central banks have experienced periods in which they have been able to influence the path of the economy without making large moves in official interest rates. They headed in a straight line for their goals. How was that possible? Because financial markets did not expect interest rates to remain constant. They expected that rates would move either up or down. Those expectations were sufficient—at times—to stabilise private spending while official interest rates in fact moved very little.”

(Here’s a shorter version by Niranjan Rajadhyaksha, research director and senior fellow at IDFC Institute, in his 2014 column: “King pointed out that the extraordinary element in this goal was that Maradona ran in a straight line while the defenders expected him to swing to the right or the left. He confounded their expectations. That is often what central bankers do to take the markets by surprise.”)

FT had also helpfully provided a link to a video of the goal.

Dig Deeper

- Maradona’s contribution to monetary theory - FT

- What economists can learn from sportsmen - Niranjan Rajadhyaksha in Mint

Free speech with boundaries

Recently, the Tata Literature Festival in Mumbai came under intense criticism after it cancelled a conversation between Noam Chomsky and Vijay Prashad, after the writers revealed their intent to read out a statement against Tata group (this again was in response to pushback from activists who criticized them for participating at a corporate-sponsored festival.)

In Mint, columnist Salil Tripathi explains why activists don’t have a case for pushing writers to boycott corporate-sponsored litfests, and why corporates should be wary of putting boundaries to free speech at these festivals.

“Once loosely-defined conditions place boundaries around free speech, commitment to the principle weakens.”

Tripathi writes: “... running a festival isn't cheap… Most Indian festivals are free. If companies should not pick up the tab, then who should? The state, given its shoddy record of protecting freedoms? In essence, the boycott issue is a navel-gazing exercise about who is purer—the writer, the activist who wants to make a point, or the company that ‘permits’ debate.

“What about readers and listeners? Aren't literature festivals about them? Keep companies out, and festivals become expensive; boycott festivals, and audiences lose again…

“Writers have a duty to speak out. They should have platforms to say what they wish, including what others won't or can't say; what others want to or need to hear. Truth achieves resonance when it is spoken to those who wield power, not when it is spoken only in narrow alleys, where the only ones listening are those who agree. Boycotting the Tata festival would have been wrong. But by not letting Chomsky and Prashad speak, the festival may have only increased the public scrutiny of its sponsors.”

Bangalore Lit Fest and Hyderabad Lit Fest have been valiantly treading a different path—depending on funding from rich private individuals, rather than from corporates. As our colleagues found out from interacting with V Ravichandar (Bangalore Lit Fest) and Ajay Gandhi (Hyderabad Lit Fest), doing it is no easy task.

Dig Deeper

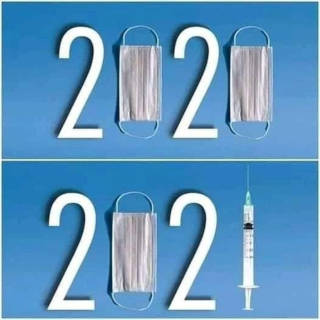

Brace yourself for 2021

(Via WhatsApp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy. Head over to our our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel