[Image by Mabel Amber from Pixabay]

Good morning,

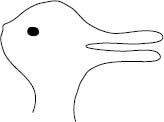

Early in his book Redirect, Timothy Wilson, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia, explains ambiguity in the real world using two simple images.

He writes: “How do our minds know how to interpret something? One way is by relying on past experience. If you have a pet rabbit, you probably saw a bunny in the picture (below). Another way is by using the context in which we experience something. When people were shown a picture similar to the one [below] on Easter Sunday, 82% of them identified it as a bunny. When people were shown the same picture on a Sunday in October, 90% identified it as a duck or a similar bird.”

By way of another example, look at the two words printed below in large type.

“Did you have any trouble reading them? ‘Duh,’ you think, ‘the first word is obviously THE and the second word is obviously MAT.’ But look closely at the second letter in each word. That letter is actually a drawing of something that looks like a football goal post with the tops bent inward. When you saw this drawing between the letters T and E, your mind instantly interpreted it as the letter H. But when you saw that same drawing flanked by the letters M and T, your mind instantly interpreted it as the letter A.”

The bunny/duck example is quite famous, while The Mat example is less so. The examples are important because they are visual, and often involve an ‘Aha’ moment. These can be timely reminders that there could be another way of looking at the world. It’s not too different from the warning given by Novelist Chimamanda Adichie about the dangers of a single story in her famous TED Talk.

What’s your favourite way to remind yourself that there could be another way to look at the world? Let us know!

In this issue

- Embrace the context

- The way to your team members’ heart

- Generation gap

Have a good day and week ahead.

Embrace the context

In their essay on Systems Change, in Stanford Social Innovation Review, authors Christian Seelos, Sara Farley and Amanda L. Rose refer to a deep question posed by US Senator Gaylord Nelson back in 1966. He asked, “Mr. President, why cannot the same [scientists and engineers] who can figure out a way to put a man in space figure out a way to keep him out of jail? Why cannot the engineers who can move a rocket to Mars figure out a way to move people through our cities and across the country without the honors of modern traffic and the concrete desert of our highway systems? Why cannot the scientists who can cleanse instruments to spend germ free years in space devise a method to end the present pollution of air and water here on earth?”

Among the many interesting ideas they explore in the essay, they also present the set of principles underlying systems approach to solving problems.

- Broad: Diffuse, messy, and ambiguous, entailing multiple pathways.

- Hidden: Validates the existence of the “things in-between” and acknowledges subjective realities, hidden power relations, and complex historical trajectories.

- Creates possibilities: Adapting to socio-political context, locally-smart approaches, and expectation of learning and identifying and building on local knowledge.

- Adaptive explorations: Evolving interventions that recognize change manifests in myriad cultural / cognitive / behavioral shifts, that will mostly defy any single institution’s control.

- Vision-oriented: No defined timeline nor pre-defined end-states, with shared visions guiding ongoing learning, and adapting co-owned by local “beneficiaries” and sponsors of change.

- Managing risk by making smaller bets: Shaping probabilities by discovering what is locally possible, desirable, and how it can be scaled. Preventing failure and/or enable healing to continue.

- Monitoring, Evaluation, Research, and Learning (MERL): Providing input to improve local decisions, sustain meaningful progress, and refine donor assumptions about social context.

We thank Arun Maira for pointing us to this essay.

Dig deeper

The way to your team members’ heart

In Fortune, S. Mitra Kalita, journalist and media executive (most recently Senior Vice President at CNN Digital) offers some effective ways to be better at mentoring.

Here’s one.

She writes: “My grandfather was a farmer and a contractor in a village in India. He was known for his honesty, and my grandmother worried "nice guys finish last" and that this trait would lead them into poverty or being swindled. She devised a system of feeding workers before they went into the fields or onto jobs. That bred loyalty and personal connection, and in her words, “They care less when I yell at them.” Nearly a century later, I borrowed the approach in the pandemic by sending colleagues meals, plants and candles to show support even as work demands intensified. Once a staffer tweeted that she was missing her mom at Easter so I sent a basket of plastic eggs and candy. Gifts need not be expensive as much as meaningful, and food literally nurtures. My grandmother was onto something: Well-fed people who feel connected to you might actually heed your vision.”

Dig deeper

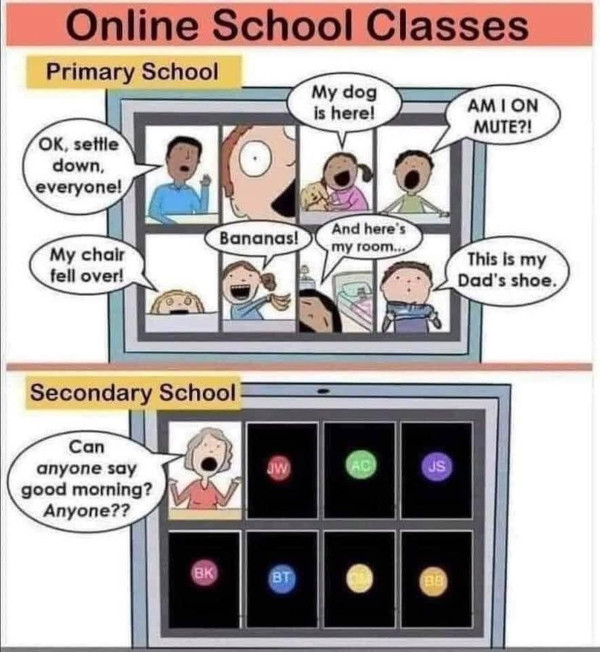

Generation gap

(Via, (still) Whatsapp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy. Head over to our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)