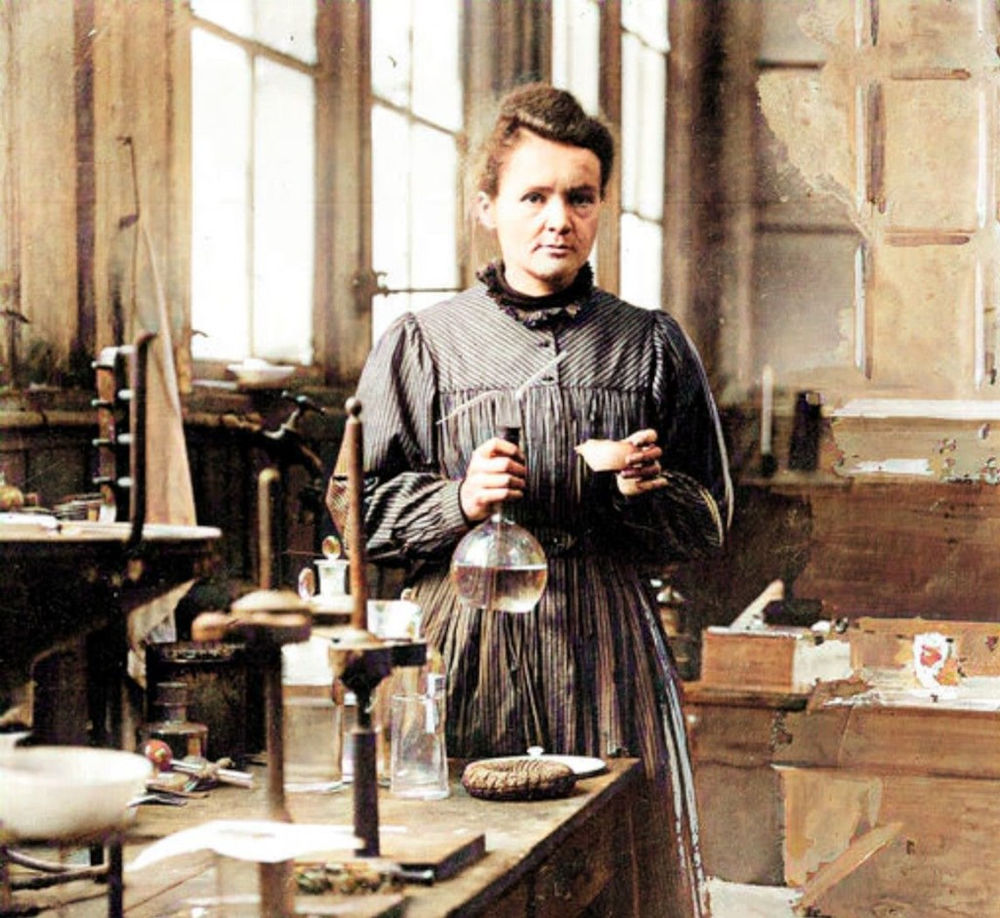

[Marie Curie. By unknown author, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Good morning,

Since the time the pandemic started, most people’s lives have been upturned. And we are now familiar with narratives of people whose careers are in a flux; or who are rethinking their current roles. But just how do you do that? Some pointers emerge in How to Find Fulfilling Work by Australian philosopher Roman Krznaric. We thought this extract, where he draws from the life and times of the scientist Marie Curie who pioneered research on radioactivity, is compelling.

“What everyone in the career doldrums really wants to know is: ‘How can I find a vocation?’ And the answer that emerges from Marie Curie’s experience is that vocations are grown, and grown into, rather than found.

“There is a widespread—and mistaken—assumption that a vocation usually comes to people in a flash of enlightenment or moment of epiphany. We’re lying in bed and suddenly we know exactly what we’re supposed to do with our life. It’s as if the voice of God has called to us: ‘Go forth and write Chinese-cookery books!’ Alternatively we put ourselves through a process of intense self-reflection which, at some point, is supposed to give us a blinding insight into our future: ‘My task in life is to set up an otter sanctuary!’ It’s an enticing thought, which, in effect, takes the responsibility away from us: someone or something will tell us what to do with our lives.

“But Marie Curie never had such a miraculous moment of insight, when she knew that she must dedicate her working life to researching the properties of radioactive materials. What really occurred was that this goal quietly crept up on her during years of sustained scientific research. After an initial desire to become a doctor like her elder sister, she did research on the magnetization of tempered steel. Only at the age of 30 did she begin studying uranium rays for her doctoral thesis, building on recent work done by Henri Becquerel. Following her discovery of radium, several more years of experiments were required to prove its existence to an incredulous scientific establishment. Her obsession grew in stages, without any Tannoy announcement from the heavens that issued her a calling. That’s the way it typically happens: although people occasionally have those explosive epiphanies, more commonly a vocation crystallizes slowly, almost without us realizing it.”

Have a good week!

In this issue

- China in decline?

- A post-iPhone world

- Social media hacks

China in decline?

All the conversations we tune in to and the literature we look up have it that China’s rise is inevitable. And that it has very good reason to view itself as a nation whose time has come to displace the US as the world’s dominant superpower. Which is why China is now showing its muscle across the world. This is why an essay in Foreign Policy that argues to the contrary got our attention. The authors draw from ancient and contemporary history to argue that when any nation begins flexing muscle, it is a sign of insecurity and an early pointer to a nation in decline.

“[I]f China’s geopolitical window of opportunity is real, its future is already starting to look quite grim because it is quickly losing the advantages that propelled its rapid growth.

“From the 1970s to the 2000s, China was nearly self-sufficient in food, water, and energy resources. It enjoyed the greatest demographic dividend in history, with 10 working-age adults for every senior citizen aged 65 or older. (For most major economies, the average is closer to 5 working-age adults for every senior citizen.) China had a secure geopolitical environment and easy access to foreign markets and technology, all underpinned by friendly relations with the United States. And China’s government skillfully harnessed these advantages by carrying out a process of economic reform and opening while also moving the regime from stifling totalitarianism under former Chinese leader Mao Zedong to a smarter—if still deeply repressive—form of authoritarianism under his successors. China had it all from the 1970s to the early 2010s—just the mix of endowments, environment, people, and policies needed to thrive.

“Since the late 2000s, however, the drivers of China’s rise have either stalled or turned around entirely. For example, China is running out of resources: Water has become scarce, and the country is importing more energy and food than any other nation, having ravaged its own natural resources….

“China is also approaching a demographic precipice: From 2020 to 2050, it will lose an astounding 200 million working-age adults—a population the size of Nigeria…

“State zombie firms are being propped up while private firms are starved of capital. Objective economic analysis is being replaced by government propaganda. Innovation is becoming more difficult in a climate of stultifying ideological conformity.”

We’d love to hear what you think.

Dig deeper

A post-iPhone world

After the much-anticipated launch of the iPhone 13 earlier this month, technology enthusiasts and gadget reviewers have been poring over the device in microscopic detail. On one side of the fence are Apple-buffs and on the other side are Apple-baiters. That is why when slugfests between these camps break out, we like to listen in to what analysts such as Benedict Evans may have to say. He doesn’t disappoint as he attempts to imagine what Apple may be at work on.

“The iPhones keep coming, with an unassailable lock on their part of the market, and Apple has spent a decade building cross-leveraged accessories and services that drive revenue and retention. And sure, AirPods are cool. But where’s the next Jesusphone?

“One answer is that Apple now has two very big projects—glasses and cars. A pair of glasses that become a display, and add things to the world that look real, seems worth trying—it might be the next universal device after smartphones, and Apple’s skills should put it at the forefront. But people have been trying for a long time: there are basic, unsolved optics problems, and we don’t know if Apple has the answer, or when it might. Apple Glasses might launch next week, or next summer, or never. Cars are a puzzle as well. Apple might design a better Tesla (and build one, with its $207bn of cash), but what problem would that solve? The iPhone wasn’t a better BlackBerry. Autonomous driving is a big problem, but is it an Apple kind of problem? Why would Apple solve a primary machine learning problem when Alphabet can’t?

“Maybe these are the wrong questions. Maybe Apple can find and solve another huge problem (or fail to solve it, as happened with TV and a few other things). But meanwhile it will carry on making a certain kind of product for a certain kind of customer. That’s been the plan ever since the original Macintosh, and in some ways all that’s changed is how many more of those customers there are.”

Dig deeper

Social media hacks

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)