[From Pixabay]

Good morning,

In Safe Haven: Investing for Financial Storms, investor and hedge fund manager Mark Spitznagel offers a number of ideas that go against the popular consensus but are rooted in strong principles. If that description reminds you of Nassim Nicholas Taleb, it’s because Taleb was his professor at NYU, and wrote the foreword for the book. You can read it here.

We are still in the process of reading the book, but already found several ideas worth sharing. Here’s one from the very first chapter.

“Investing is a process that happens sequentially through time. Investing is not static. It does not occur in just one interval of time, nor in many intervals of time aggregated together as one. (Albert Einstein purportedly noted that ‘the only reason for time is so that everything doesn’t happen at once.’) Time is the medium through which life takes place, and so it is the medium through which investing takes place. We are stretched across time. Investing and risk are a multi-period problem; and returns are an iterative, multiplicative process. They compound: In each period, we generally invest what we are left with from the last period. Like the geometric growth of offspring across generations, we parlay our capital. This principle fundamentally determines the nature of investing and the way we need to think about and interpret returns.

“But as obvious as it is, just try telling that to a hedge fund manager whose incentive fee is based on annual performance: investing happens through time. Or, deliver that message to the pension fund that is harshly judged on its ability to meet an annual benchmark over the short term rather than over a timeline consistent with its beneficiaries. And try telling that to the economics and behavioural finance communities who label behaviour ‘irrational’ when it doesn’t appear optimal within their single-period, timeless framework. Do so and you should expect funny looks. But they criticise what they can’t understand; they’re no Einsteins.”

Have a great week ahead!

The Awards Economy

It appears anyone who is someone now has an award to show-off. But just what does it mean? It feeds into people’s need for validation and oils a well-run, parallel economy, argues Santosh Desai, CEO of FutureBrands. His essay on LinkedIn got our attention right away.

“Entirely new categories of awards have sprung up all over us making sure that none of us feel left out. If earlier winning an award meant that you had to be the very best at something, today such exacting requirements feel dated. Awards are no longer given for doing anything remarkable, but merely for being wonderful,” Desai writes.

“Many companies have figured out that awarding people who are important to their business is the most efficient sales promotion tool at their disposal—after all, large customers might baulk at being given an open bribe, but who can resist the charms of being anointed the ‘Pharma Supply Chain Inspiring Leader of the Year’? To receive such an award in an audience of peers at a glittering (never gleaming or shining or iridescent) ceremony is one of those innocent joys of corporate life that it would be cruel to deny. For employers too, awards are a good motivational tool that keeps their people feel recognised on the cheap.

“A new breed of awards has sprung up that have monetised our hunger for recognition. Media houses now are ready to confer grand sounding trophies on all those willing to pay the price. We can now buy awards or more accurately, contribute to the advertising effort of the media title question in return for the recognition that they have determined that we were worthy of.”

Worth thinking about, isn’t it?

Dig deeper

Hybrid and remote is the future

When the lockdown compelled us to work remotely, that was when we started to think about what the future may look like. This theme continues to be debated and was under intense scrutiny at Davos 2022 that concluded last week. While leaders are keen to get their people back to work, research from every part of the world has it that people don’t want to return full time. They would much rather work in hybrid mode or remote. This is a theme we have been following very closely at Founding Fuel. In fact, why leaders must prepare for hybrid workplaces is a theme we had done a deep dive on with Tsedal Neeley of Harvard Business School and Bhargav Dasgupta, MD and CEO of ICICI Lombard.

This is why a report in Business Insider on the theme had our attention. Their conversations have it that people who have experienced remote work and are transitioning to hybrid are unwilling to go back to the way things were before.

“The majority of firms that have adopted a hybrid-work model since the pandemic began operate what Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford professor and remote-work expert, refers to as the 3:2: or ‘Vanilla’ model, where staffers split their time two days at home and three days in the office. His and other studies suggest that the majority of workers who can, want to split their time between work and home.

“Apple CEO Tim Cook’s ongoing battle with staff over mandates that workers should be at their desks on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays is indicative of the challenges companies can face. It has already seen one Apple director quit.

“Flexibility often means different things for different generations, staffing giant ManpowerGroup’s regional president for Northern Europe, Riccardo Barberis, told Insider of the firm’s in-house employee survey.”

We’re keeping a hawk eyed watch on how this narrative evolves.

Dig deeper

- Forcing staff to return to work full time is unrealistic (Business Insider)

- Reimagining work in the post-pandemic world (Founding Fuel Masterclass)

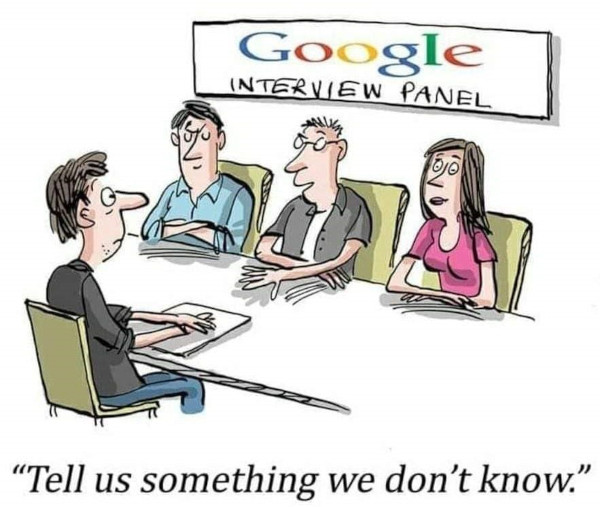

A tough question

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel