[From Unpslash]

Good morning,

Mention terms such as web3, crypto or non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and most people sit up. Because, these are in the news and most of it appears confounding. On the one hand, there was a decision by the government to tax cryptocurrencies at 30%. Then on the other hand, the RBI doesn’t think of it as legal.

Then there are investors’ attitudes towards cryptocurrencies and NFTs. Some of the biggest investors such as Mark Mobius and Jamie Dimon think it is best ignored. Others such as Elon Musk and Paul Graham, founder of Y-Combinator, are convinced it is where the future lies.

It is not surprising that some have chosen to stay away; and yet others want a piece of the pie. Be that as it may, there is no ignoring the debate. On scrutinizing the landscape, we believe the underlying technology is where the future lies. But just how do we begin to understand it all?

To wrap our heads around it and cut past the clutter, we asked Tanuj Bhojwani, co-author of The Art of Bitfulness, to begin by putting this explainer in place. This isn’t investment advice. Think of it as first principles. It is the first in a series and over the next few weeks, we’ll dive deeper into the theme and host conversations on Twitter Spaces with him and other guests who understand the domain.

Stay tuned. And write in with your questions, thoughts, and comments.

An Intelligent person’s guide to crypto

Imagine this: Asif has to send a large amount of money from Delhi to his friend in a distant place, like Baghdad. There are problems with whatever methods he chooses. He could carry a bag of money himself to Baghdad, but it would be time consuming, and the thought of carrying that much cash scares him. He could send the money with someone he knows, but what if they don’t deliver it?

So Asif's younger, hipper friend tells him about this cool new thing. It allows you to send money across borders and all Asif and his friend need is a simple password. You’re probably thinking of cryptocurrencies, but there’s one minor problem. Asif lives in the 8th century. This cool new thing is not crypto, but Hawala—the decentralised Western Union of the Silk Road.

Everyone thinks crypto is some newfangled, complex mathematical technology. It is, but going down that route leads to missing the forest for the trees. A much more helpful paradigm is to see how much of it is actually just really the same old solutions but with new tools. Like a pan, but made with teflon. It may be non-stick, but at the end of the day, it's still a pan.

So today, I promise you a crypto explainer that will not try to tell you what a blockchain is. Instead of trying to understand cryptocurrencies by breaking them into their components, the aim of this article is to distil its essence by looking at other financial systems. We will refer to all these related and slightly different technologies under the broad umbrella term web3. There’s debate even over that term, but we’ll just brush past it for now. Like I said, forest not trees.

This exercise will necessarily mean foregoing some nuance, ignoring edge cases and making generalisations. Hence, none of this is financial advice, nor is this intended to be precise. It is still, hopefully, accurate. The purpose of this article is to look beyond the hype and ask the bigger question:

What is the case for cryptocurrencies or web3 in twenty years?

To answer that, we’re going to have to deal with three important ideas: Trust, Composability and Permissionless Innovation. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves, and start from the very basics.

The time machine

At its most basic, finance is the art of moving money through time.

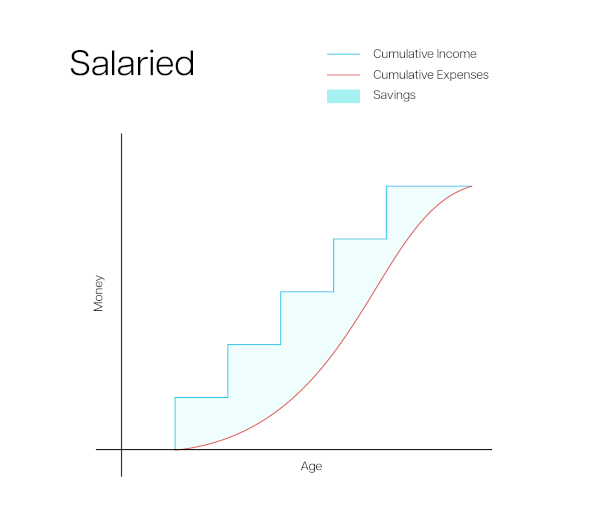

If you’re a salaried professional, your income stream is a steady drip. Every month you get paid a fixed amount. You can plan your expenses and hopefully, you even have some left over each month. Over a year, your finances look something like this:

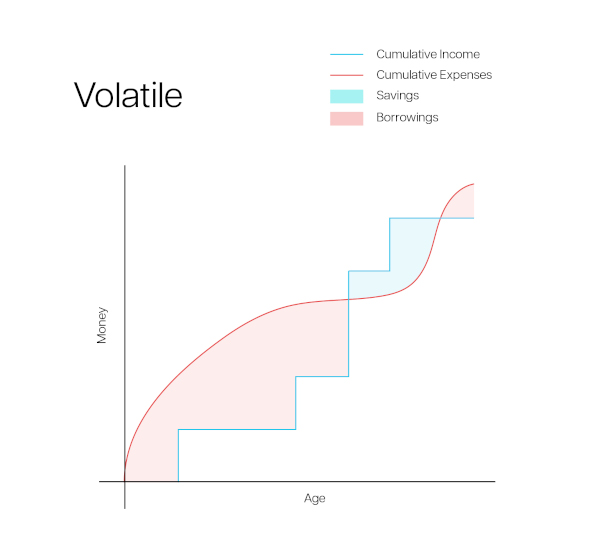

But for a majority of people in the world who aren’t in white collar jobs, money is more of a wild ride. If you’re a farmer or a wedding photographer in India, your income is seasonal. There will be periods when you need money and periods when you have more than enough of it. Or maybe you’re a businessperson. You need money today to start your business, and in a few years you’ll be able to pay it all back and then some, with your profits. Their financial lives look more like this:

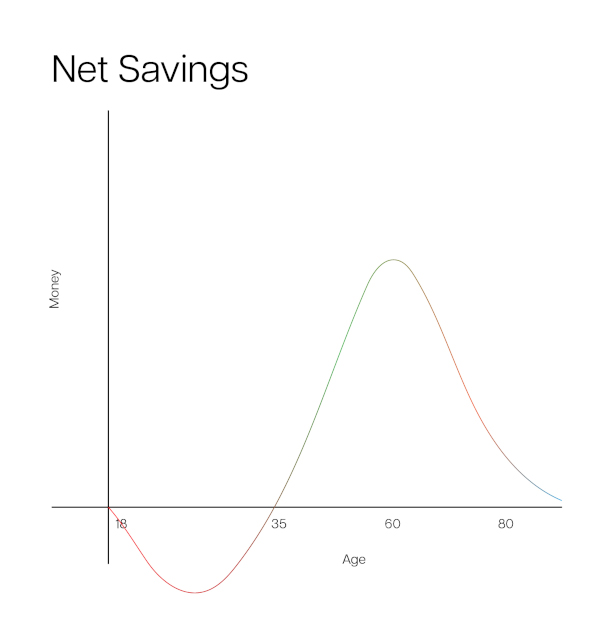

When you have income more than your expenses, you save. When you have more expenses than income, you borrow. This sounds like two simple and separate activities, but both these sets of people need each other. If everyone had enough money, your savings would mean nothing. If everyone needed to borrow money at the same time, who would lend?

Thankfully we live in a diverse world with people of all sorts of professions, ambitions, risk appetites, and ages. If you zoom out far away enough, the financial lives for most of us look like this:

So if you find someone whose monetary needs are complementary to yours, the two of you can exchange money for time. The person with excess money gives you funds today, in the expectation that you give them back more money than you took at a future date.

In theory, this sounds simple and great. In practice, this is a nightmare.

Why finance was always local

There is a supply of money, and a demand for money, but matching this supply and demand is hard. Based on the chart above, someone at age 25 can borrow from someone at age 50.

However, in real life, you don’t ask your father’s friends for money or lend to your relatives with interest. It is difficult to find the exact person whose financial needs are the perfect complement to your own. Our ability to finance our lives is bottlenecked by our ability to coordinate.

Unlike any other barter where two parties exchange something of equal value, in any “financial” transaction, usually one party is giving money now, against a promise of future payment. Thus, all financial transactions have a supercritical component—trust.

Before the modern banking system, communities got around this by building their own financial products within a community of trusted participants. For example, the 8th Century Hawala system. Which transferred money without physical movement of money. Interestingly, the word Hawala in Arabic means both “transact” and “trust”.

Or take the example of an “innovative” old-school financial product like the chit fund. Communities pooled resources into one fund, and allowed whoever needed the money most urgently to bid for it.

The lowest bid won, and the difference between the pooled amount and the bid amount was the “profit” for the community. However, so were the losses. There are perverse incentives to not pay back, or worse, run the scheme as a ponzi. Which is why these schemes were restricted to be local. Back in the day, you could only trust those whom you knew.

Obviously, this system had its limitations, and could not grow beyond a certain size. This is where the financial industry comes in.

Finance and the art of unbundling

The finance industry is a middleman built to match this demand and supply of money.

Thankfully, unlike other things we need like cars or sofas, where we may have particular tastes, money is fungible (we will cover all things non-fungible in the next article in this series). Which means that except for matters of convenience, you don’t really care if you get your Rs 10,000 loan from person A or B, as long as it is Rs 10,000.

The financial industry takes advantage of the fact that money is fungible, and creates financial products to match different financial needs of money and time. They accept money from suppliers wherever possible—your banks will happily accept deposits, most fund managers would gladly accept more Assets Under Management. Then they try to give that money to people who want it, like borrowers or businesses, who are willing to promise to return more money in the future than they took today. By bundling and unbundling the money in various layers of abstractions, the finance industry thus clears as much of the market as it can. It’s like a coconut tree—you can grow one tree and sell different parts: the husk, the shell, the water, the leaves, etc. to different buyers.

That metaphor is not entirely superfluous. A lot of the finance industry does have its route in commodities. Much in the vein of Hamilton, there’s a popular musical running in London’s West End called the Lehman Trilogy. It tells the story of the three original Lehman brothers, and how they started as running a dry goods store, and diversifying into cotton. Eventually instead of selling cotton, they started selling the option to get cotton. Eventually leaving the trading of commodities behind entirely to get into the business of trading money.

Over the last two centuries, our modern financial system has grown in this manner, matching supply and demand of money by creating new financial products. Alongside, through a series of scandals, we’ve also grown the modern system of regulating the finance industry. We think of the modern financial system as “safe” or “trustworthy” because of these regulations and force of law that prevents fly-by-night operators from running scams.

In theory, this is a beautiful system of checks and balances that auto-magically works. In practice, things can get messy. We all remember the 2008 crisis when the banks accepted money from investors by selling them collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and then tried to create demand to match that supply by giving subprime mortgages to people who shouldn’t have gotten the loans in the first place. When the bubble burst, it really burst. But it is from these events that new rules are born, which add more safety in the first place.

So far, I’ve not said a word about cryptocurrencies. What’s all of this got to do with the future of cryptocurrencies? That’s where the third idea comes in—permissionless innovation.

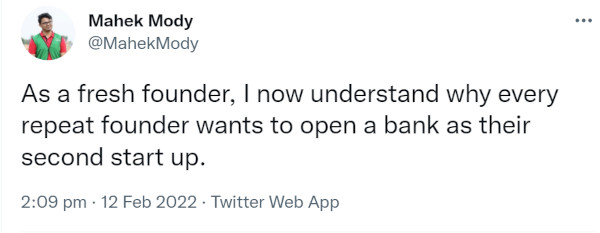

How software is eating your bank

Recently, there’s been a boom in fintech funding, both in India and globally. The driving force in the thesis for fintech is the same—banks are too rigid to innovate as rapidly as outsiders can. The finance industry has become so tightly regulated, one could theoretically argue they leave not much room for innovation. This tweet probably best captures the sentiment:

With the internet enabling multiple revenue streams, multiple new fintech product offerings on both credit and investments, entirely new asset classes—our own financial lives are also getting increasingly complex.

To solve this, on one hand, you have startups like Plaid or Setu, which are trying to abstract away the difficulty of working with a bank, and trying to make available basic financial products as APIs for other fintechs to build on. They’re trying to offer composability as a service.

On the other hand, you have decentralised finance. This is why I believe that the twenty year case for cryptocurrencies is very strong. I said earlier that the ability to create suitable financial products is bottlenecked by our ability to coordinate. The internet has lowered that barrier tremendously. We can now exchange information, across the globe, in real-time.

But our money still sits in banks.

(There’s an interesting aside here about the idea of the “original sin”. In our recently launched book, The Art of Bitfulness, my co-author Nandan Nilekani and I talk about how the inability to send money online led us into the problems of web2.)

In decentralised finance, your “account” is now a free agent. It is an entry in a global ledger that everyone is maintaining and watching. What a lot of regulations tried to prevent by threatening the force of law, is now assured by the power of mathematics and game theory. You don’t need a regulated bank or an intermediary to maintain your account or assets with trust. A lot of blockchains claim anonymity as a feature, but in practice, the blockchain is radically transparent. Take the recent example of Melania Trump and her NFT collection “Head of State”. Chain analysis found that the transactions seem to have been funded by herself.

When your account is your own “free agent”, your bank can now be a piece of software. Web3 allows near limitless composability. You can create and set up as complicated a financial transaction as you want.

The most important feature that gets unlocked with this high trust and high composability future is the ability to have permissionless innovation. Take emails for example. Once the fundamental SMTP protocol to send and receive emails was established, we could have rapid innovation on the front end. Even though email is now a 50-year-old technology, we still see apps like Superhuman come in and improve the email experience when the incumbents no longer do so. The most important part is that, unlike the financial sector, they did not have to take permission from anyone to innovate.

When you combine the trustless financial transactions with these other innovations happening in web3 such as decentralised autonomous organisations (essentially a board where the votes are transparent), you can get cool, new things that never existed before. One such example is KlimaDAO.

KlimaDAO describes itself as “a black hole for carbon at the centre of a new green economy”. In their own words they do this by “increasing access and demand for carbon offsets, we make pro-climate projects more profitable, while forcing companies to adapt more quickly to the realities of climate change.”

Basically, a bunch of anonymous people got together to finance a radical idea. The carbon offset market has become like any other financial market. Companies that can easily recycle some carbon, sell their offsets to companies that heavily pollute. In theory, the polluters are offsetting their carbon, but there’s complaints that these offset markets divert funds away from true investments in R&D of green technologies that will reduce our dependence on carbon altogether. KlimaDAO accepts money from anyone on web3. The people who invest in KlimaDAO earn interest on the bonds that KlimaDAO issues. It uses the money raised to earn carbon credits and lock them up, driving up the price of carbon offsets. Think of the shortsqueeze from early 2021 that Redditors unleashed on GameStop stocks by refusing to sell, but for carbon offsets. In just six months between October 2021 and February 2022, KlimaDAO claims to have absorbed nearly 16 million tons of carbon, the equivalent of saving nearly 80,000 hectares of forest.

What Jaspal Bhatti can teach us about history

Of course, the lack of regulations is still a big source of concern in web3. While you can trust the transactions on a blockchain, web3 makes it even harder to trust the people behind it because of anonymity, and lack of consequences/accountability. There have been many “rug pulls”, projects that seemed legitimate, but eventually ran away with people’s money. There’s a lot of growing pains, and a lot of bad actors on web3 currently. In fact, it is statistically more likely the new coin you hear about is a scam than legitimate.

But this is true of a lot of early financial systems like this Jaspal Bhatti video shows us. Replace “Public Limited” with “Cryptocurrency” and “IPO” with “ICO” in this video and you’re basically looking at the same problems. These are not crypto-native problems, but human problems. Or more recently, you may have been as shocked as me to find out that a faceless yogi was allegedly driving decisions at the country’s leading stock exchange. But then again, these are anecdotes, not data.

In twenty years, web3 (or web6 by then?) is more likely to look like the financial system does now—much tamer, much more accountability, some regulations but wildly more possibilities than the current financial system allows. The possibility of permissionless innovation opens up a future that we don’t understand yet. We don’t know what we don’t know. All I am willing to bet on is that this new financial infrastructure cannot be ignored.