For those among you, who have been attentive in the last eight years, you may have known that I am apt to write a blog predicting the Oscars. All those years ago, I started writing for an online magazine. This year the kind folk at Founding Fuel have invited me to write on their platform. With humility, it feels like an octagonally perfect circumambulation. I would like to thank my producers and my director, without whose support I wouldn’t be here today.

This year has been a fantastic year for movies, and an even more fantastic year for the action spectacle. Northman, Avatar, Wakanda Forever, The Batman, Top Gun and RRR have all pushed the boundaries of cinematic craft. Nope and All Quiet on the Western Front, though not of the genre, also have their huge action set pieces. And then there was the genre defying Everything, Everywhere All at Once. Unexpectedly a huge chunk of these movies have been given deserved recognition at the Oscars, despite being a style not usually celebrated by the fraternity. For any aspiring action director, who wonders what links these films, and elevates them above the usual (I’m looking at you Antman and the Wasp), it is pathos and consequences.

Unlike other years where there have been some disappointing movies that have snuck into the best picture race, this year’s is a strong debut. Personally, I may have had The Whale and Decision to Leave kick out one or two on this list. She Says is a film worth your time, but I understand why it’s not featured. Northman might be too out there, but so are some of the other films in here. Overall, I am ebulliently happy with several of the films on the list (I have been despondently disappointed in others). Anyway, you’re here to hear me vociferate (though there’ll be more pontification and less denunciation than most years), so let’s roll up our sleeves and get to it.

Best Film

I honestly don’t think Elvis should be nominated. It greatly simplifies a complex narrative by giving the film a villain whose degree of villainy we did not need (also proving that Tom Hanks is too lovable to be a convincing villain of any sort).

[Elvis]

Director Baz Luhrmann who as a young man took risks into maximalism (more on that later), could have had an auteuristic hand, but lazily decided not to. I would like to imagine a younger Luhrmann lathering the film with artifice and wrecking us when human reality joists its way through the cracks. Here we strive towards reality but never get there, and strangely enough it is not because the lovely (I never felt Elvis was attractive until I saw this actor) Austin Butler is doing a bad Elvis impersonation, but because Tom Hanks is doing a bad impersonation of heaven knows what.

Though technically very strong, Avatar: The Way of Water, because of an absolutely lackluster screenplay, is second last from the top. The chief villain has no reason to exist, and the extent that he goes to, given his motive, sparks incredulity. In fact, this makes the movie feel “movie like”, and pulls us out from what could otherwise have been immersive and real world building. The main duo, played by Sam Worthington and Zoe Saldana, does not take time for us to be rooting for them in this film. So, unless you’re still invested from 10 years ago, you’re not immensely worried on their behalf. Shout out to excellent work from both Kate Winslet who plays an unrecognizable queen figure and Sigourney Weaver who at 73 years old is playing a 14-year-old with arresting persuasiveness. I wish James Cameron was less of a dictator director, and surrounded himself by people who would challenge him. There is no doubting his absolutely massive talent, but filmmaking is a team sport, and if you carry the entire weight of it on your shoulders you’ll take a long time, and the weaknesses will show (in Cameron’s case, dialogue and working with actors).

I did not expect Top Gun: Maverick to be as good as it was. But it simply isn’t a standalone film. Much of its pathos derives from the original, and my earlier mentioned consequences wouldn’t have any impact without the back story. It’s a clever film, both circumventing the problems of the old film (but also heavy-handedly recasting the female love interest) as well as embracing what made it work (just a dash of volleyball induced homo-eroticism). Much of what makes it good, is because one comes in supposing it to be standard blockbuster fare, but it is more than that. It is almost certainly a deserved must watch for any cinemagoer, and the ‘making of’ is almost as interesting as the film, but it is super unlikely to win top prize.

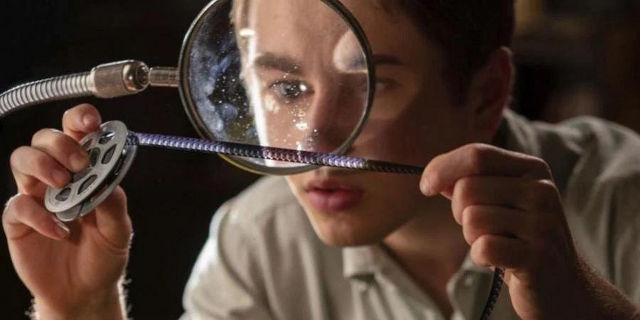

Next up is Spielberg on Spielberg, The Fabelmans. Though not as vividly astounding on a technical level as West Side Story, you definitely see what a visual master and excellent camera choreographer Steven Spielberg is. Though somehow the film doesn’t have the heart of, let’s say, Licorice Pizza; it never manages to capture that slice of time. The biggest problem I have about it is how the lead is written, as mostly a blank slate. This may well be how Steven saw himself when he was young. But unless you’re in World War I, a film where things mostly happen to you is not exceedingly interesting.

[The Fablemans]

The second aspect I didn’t like — in fact more immensely the more I think about it — is that Steven paints Sammy as a natural born film making genius. There simply isn’t any struggle whatsoever. Gosh, that is dull dull dull. So, we inject the drama externally. I won’t spoil the picture for you, and the external drama is well injected no doubt, but in the long ranking of Spielberg’s masterpieces, this shouldn’t make the top ten. (And you have to admit, it’s a bit arrogant to remember to give Lincoln character flaws, but forget to give yourself any.)

Surprisingly low on the list is the terrific Women Talking. I am glad that Sarah Polley tried her hand at directing, and I think she brims with potential, but her inexperience does show, and this is the only factor that doesn’t thrust this film forward in the rankings. In weaker years, with stronger direction this film would have stolen away best picture — that just goes to show how compelling the contenders this year are.

[Women Talking]

Polley gets several things right. The women are distinct in their personalities and immediately recognisable in any frame (which is by the way surprisingly difficult to do with hair-style-less women all of the same skin colour — for instance, Claire Foy, Rooney Mara and Jessie Buckley are all around the same age and build). Each of the (more than 6) women have a collective identity as well as distinct and consistent points of view. The film also uses humour very cleverly, elevating both the struggle of the decision as well as cementing these people as everyday women. The film is almost entirely just conversation, with a universality of space, time and action. There’s also a very clever insertion that re-contextualises everything you have heard before with just one scene. A better film than the haunting She Says. I like (if like is the right word), that both films do not suddenly turn their lamb protagonists into raging firebrands. Consideration in the face of injustice is heroism.

Once again, surprisingly low on the list is All Quiet on the Western Front. Unlike Women Talking, this film wouldn’t have won in some of the previous years, because it’s outdone by similar films like 1917 or Dunkirk, though it deals with consequentialism better than either of the other two.

[All Quiet on the Western Front]

The source material, one of the most widely read books in all of German literature, sorely needed a German adaptation. (The title translates to “There’s nothing new to report on the Western Front” and is even more haunting in the original language). Eighty percent of it is brilliant, finely tuned, grievous and surprising. The full film is relentlessly and stubbornly forlorn. The scant but memorable score is instantly haunting and arresting. But, like Joyeux Noel, it suffers from a swatch of predictability. I’m surprised that Felix Kammerer isn’t nominated for best actor. Scenes that move from brutality to empathy could have been contrived in the hands of a lesser actor, but he reaches into a deep core of believability. Naive yet broken is hard to do, and Felix, and many of the supporting cast handle it beautifully.

It’s quite tricky to pick which of three films should come in at fourth place, but I’m going to choose Triangle of Sadness. This is an odd film both because it’s a lot of people’s favourite film and no one expected it to be nominated for best film. It is a carefully constructed, yet callously erratic film. In a sense it’s not one film at all, but three, each having a separate beginning, middle and end. It manages to be both repugnant and alluring, and has a staying power beyond the norm. I personally think the end of the second act, which is icky beyond cause, will be its undoing. Though director Ruben Ostlund is doubtless a masterful artist, his mind is that of a film student, drawing inspiration indiscriminately from several great filmmakers and stories. There’s nothing wrong with that if it aided in telling a more compelling story, but in his case it was more drawing on these sources to say where the film is going to go next. It is nonetheless a brilliant, oft times confusing, always lush film.

Third from the top is Tar. Given how short and unassuming Todd Field’s directorial filmography is, this is a remarkable achievement. As a writer, he has a bit left to be desired, throwing in references that are too steeped in those who know, and giving very heavy-handed exposition. But as a director, he’s deft. Cuts are bold. Sound is well used.

[Tar]

The language is hard, and kudos to a strong cast making the dialogue feel as if their character has just thought it. He can stay in a scene a tad too long, which can try attention spans, but these are the Oscars, and challenging films is what we’re all about.

Dialogue is on masterful display with Martin McDonagh’s Banshees of Inisherin. McDonagh is a mischievous scriptwriter (not so much in his staggeringly fantastic Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri, but otherwise). Banshees of Inisherin does show his roots, it would have been a more powerful play, where much is imagined, than an abstract movie. Still, the beautiful landscapes counterpoint the dark themes.

[Banshees of Inisherin]

One character’s existentialism is absolutely irreconcilable with another character’s exasperation. Hollywood is all about escapism and fantasy, but it mislikes a diversion from logical consequentialism, which makes this absolutely refreshing. I’m not sure how to explain this. But English cinema likes to put characters in a situation, and say something along the lines of ‘in this kind of situation, this is how you might react too’. McDonagh will have none of that. This may also explain why Waiting for Godot is always a successful play, but has never been a successful movie.

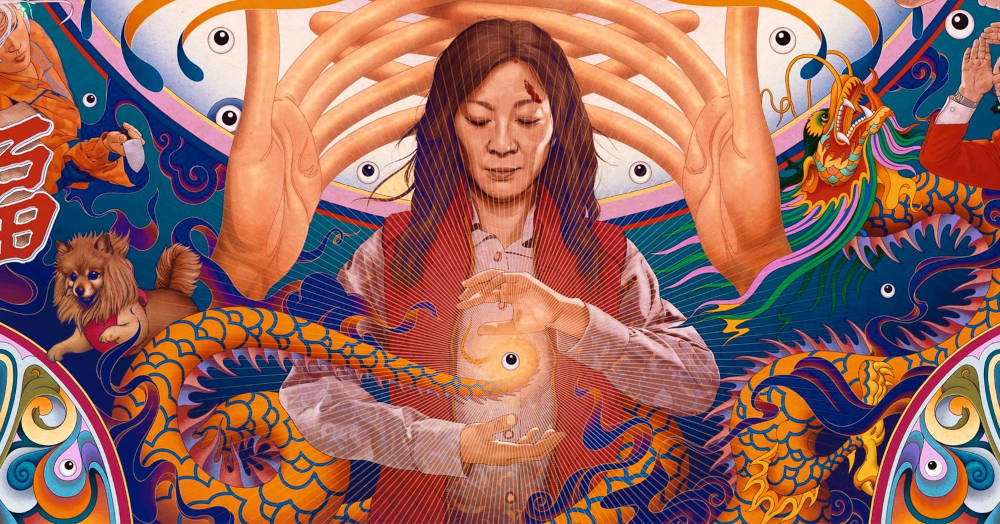

I think it’s going to come as no surprise to absolutely anyone when Everything, Everywhere All at Once comes away with the top prize. The directors, Daniel and Daniel (and this is true), decided that if they were going to waste people’s time, they’d better attempt to change their lives. It is not a hyperbole to say that they very well might have done that. Out-maximalising Baz Luhrmann, out choreographing Steven Spielberg, and out-multiversing the verses out of the Marvel cinematic hedonistic heroism, Everything, Everywhere All at Once is exactly what it says on the tin. It’s the first truly post-internet film, with attention grabbing Tik-Tok sensibilities put on glorious display. It is rare in a generation where there is a marker in cinema. I’m reasonably sure that admirers and imitators will follow up, and Everything, Everywhere All at Once is going to displace much that has come before, after, or even itself during its own runtime.

[Everything, Everywhere All at Once]

What makes the film is its magnificently gigantic heart. It shows you Everything and asks you ‘What about this one thing?’ It says there’s so much grabbing at your attention, between the Queen’s death and the war in Ukraine, and says should you care equally about everything? And it says, well, let’s start with the first thing. It takes the difficult-to-explain trauma of an inundated teenager and says, ah, I might have a solution for you. Your fractured attention span requires our attention and Everything, Everywhere All at Once tells you that the enemy of love is inattention and the enemy of hate is understanding. It can only deliver this trite rainbow painted care-bears moralism by fuelling it with the full force of unadulterated conviction in its cause. It was the wisdom for our time, that we never knew we desperately needed.

Just as an aside, isn’t it fantastic that in the same list we got the monochromatic Women Talking and the meta-chromatic Everything, Everywhere All at Once? What a time to be alive and be a fan of cinema.

Best Director

Let it be known, hereby and forever more, that James Cameron is a master director. Plot the blockbustiest blockbusters of all time, and realise that all the peakiest peaks that soar above the remainder are James Cameron films. He is inventive, he is technically sound, he’s visionary. He’s quite literally a man without limits.

And the best director nominations are so chock full with more talent, that there wasn’t room for him this year.

Last from the top is (can you believe this is real), Steven Spielberg. It’s not that he’s lost any of his natural chops, it’s that he isn’t really an actor’s director. In fact, he’s so studied by directors, that his template (ahead of his time in his prime) was the high-water mark for editing timing and camera movements. Having not changed his instincts, many of the directors on this list come across as more daring than him. Master he is, Auteur he is not (not in The Fabelmans anyway). In fact, Robert Eggers should have made the cut instead of him, even if The Northman didn’t get nominated for best film.

Todd Field, through no fault of his own, comes in second last (For Tar). His craft is impeccable, and he’s very allowing of his actors, of this there is no doubt. He makes daring moves on the edit table, and has a first-class eye for lighting and chroma. His work is best viewed in the micro though, and when you zoom out, to the macro, you can see his weakness. Someone should allow him to direct the ninth episode in Game of Thrones (all masterclasses in balancing the micro and macro, but only the 9th episode), and he’ll come away as a talent unstoppable.

In the middle of the pack is the always nuanced and always manic Ruben Ostlund for Triangle of Sadness. He manages to spot or make stars out of all his unknown actors.

[Triangle of Sadness]

He brings humour in grief and beauty in the unkempt. His script is a little random, but after having settled on it, he’s totally in control, extremely certain of every frame, timing and movement. If he wishes to disconcert, or attract, he has the ability to do it through craft alone. In many ways he’s a kid running rampant, but in symbolism, leitmotifs, and the inconsequential leading to gravitas he has a finely tuned maturity.

Second from the top is the powerhouse of Martin McDonagh for Banshees of Inisherin. While James Cameron or Steven Spielberg might be experts of the syntax of film, McDonagh has an ear for poetry. Every scene is beautiful, many parts add to the whole. Consistent, measured and contributing to the major arc of the whole film. While other directors on this list may be saying “look at me and admire my craft”, Martin is saying “Why don’t you think about what I’m doing”. While James Cameron might be artificially constructing each element to look perfect and have ideal timing, Martin’s landscape decides to be perfect and have perfect timing, just because they feel he’s worthwhile doing that for. (There’s a small scene, where Kerry Condon’s character is reading a letter at a window. For some reason, birds, reflected in the window decide to fly at just that time, motivating her character to look up. In that glance, you get to see what she was thinking. How on earth do you orchestrate something like that?) It’s for that reason it may just be Martin that wins top prize but for our prime contenders.

If all these directors were given an exam and a tight brief, I think the Daniels (Kwan and Scheinert) would probably get the least marks. Give everyone a shoe string budget and ask them to make a music video, and the Daniels will make it viral.

[The Daniels]

The Daniels aren’t strong in many spheres of directing, but they are resplendently creative. They make ingenuity a competition, adding layers beyond the point of limitation (a process called putting a hat on top of a hat. A single goofy looking hat is goofy, but layer several goofy hats on top of each other, it becomes masterful). They aren’t so much daring as they are a muddly mess. Yet within the realms of the Oscars their sensibilities are radical, of the times and revolutionary. And just when you think they’re all flashbang and no substance, they whip out the emotional sledgehammer that was hidden up their sleeve all along. I’m hoping the Daniels take away the prize. It might not happen, but I really hope they do.

Best Actress

Best Actress is an intriguing two horse race. It’s actually much closer down to the line than anything else on Oscar night. On the one hand you’ve got the only actress who can give Meryl Streep a run for her money.

[Cate Blanchet]

Cate Blanchett is cerebral, emotive with an incredible vocal range. In fact, the only aspect where I haven’t seen her totally exceptional is her ability to act with a range of physicality.

In the meantime, Michelle Yeoh acting in English is already at a disadvantage. She doesn't have a great deal of vocal range, and will naturally struggle with accents or inflexions. But her physical acting, which extends to a quickness of facial expressions is unmatched by anyone in the industry.

[Michelle Yeoh]

In Everything, Everywhere All At Once there’s a point where she enters into a white room, and her face is disoriented, is taken aback by her surroundings, focuses on the other actor and resolves itself to a difficult task in a matter of seconds (possibly less than 2). There’s another scene where she’s meant to re-realise that she loves her husband. And the lights on her face change rapidly and radically. Her facial emotions change, and are absolutely heart wrenching. But she’s acting essentially against multicoloured LED strobe lights staring at her.

Yet, although Michelle is skilful, mesmerising and perfectly cast, in every universe, she’s definitely Michelle Yeoh. One can’t but wonder if Cate was in a similar situation if she would manage to get lost in every role that she places herself into.

This one is too close to call, but I think it’s ultimately going to go to Michelle Yeoh. Tar is craftedly Oscar bait. Cate has the difficult acting challenge of sounding contrived (because the character is full of herself), and emoting on her face, which is difficult to stream genuineness from. In 10 years, the role will be largely forgotten, while Michelle Yeoh’s will be acutely remembered. Michelle’s role is not without shortcomings, but where she needs to bring it, during the periods of heightened emotion, Michelle doesn’t miss a step.

Best Actor

Usually, actresses have comebacks. They get older, roles shrink and disappear, and suddenly they get cast in something perfect, and the world marvels at their rediscovered talent. In an odd reversal of gender, this has happened to two of our men, Brendan Fraser in the Best Actor category and Ke Huy Quan in the Best Supporting Actor category (though I really think he is the male lead, so should by all metrics be “Best Actor” — for instance Michelle Williams is nominated for Best Actress, not Best Supporting Actress, and I think they have roughly the same screen time and bearing on the film).

I haven’t seen Living or Aftersun. Put it down to callousness on the job.

Austin Butler is alright. He’s a competent, but not an exceptional Elvis. The trouble is not him passing for Elvis, the trouble is bringing depth, nuance and heartbreak with his acting ability.

Colin Farrell is a far better actor than we give him credit for. Just compare him as the Penguin from The Batman and the guileless clod in Banshees of Inisherin. Quick talking, personable yet incapable of putting another first, and with permanent confusion on his quizzical eyebrows, he’s a perfect foil to Brendon Gleeson’s bitter tired character. They’re a bit like an extreme Laurel and Hardy duo between them.

[Banshees of Inisherin]

But Brendan Fraser is going to take away this award for his morbidly obese home-bound professor in The Whale. In truth, he’s always been a good actor. He moved from comedy hero to action star. Here he plays intelligence (he normally plays idiot). I’ll tell you how I know that Brendan is a good actor. He is always, and I mean even in terrible roles, listening to his co-star. You can always see him registering and understanding what his co-star is saying. That’s a great level of attentiveness, and is a constant Brendan trait throughout his career.

[The Whale]

In this movie he steals it away. And there’s plenty of available pathos and struggle in the movie to help him. It’s not easy acting under prosthetics, and Brendan manages to convey so much through his bright eyes. His hand movements are absolutely on point every time. He is completely believable, and his every decision is precluded by a tonne of facial expression setting it up. He also manages to lure the audience on his side entirely with one facet, finding joy in small things. It would be so easy to dislike this character, or simply pity him, and distance ourselves from feeling his pain, but Brendan, through his stunning ability makes us very much side with him and find the Whales inside of us. The film wasn’t nominated enough, and is certainly worth your time, and both the price of admission, and the cost of the tissues you’re going to go through while watching it.

Best Supporting Actress

This is an unusual race, and not a very strong line up. The win will probably be Angela Bassett — strong, commanding, who focuses her sadness into rage. While most actors in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) spend their energies minimising their breadth of expression to try to act cool, Angela is cool. So instead, she spends her energies extracting every inch out of terrible dialogue. I urge you to read the dialogue before you watch this scene, and you’ll understand what I mean. The words on the page are like those in every other Marvel film. Without poetry. Stating facts and getting where it needs to as quickly as possible. Yet she extracts everything from them. And in this scene, deciding not to start angry is a genius move.

I don’t think Hong Chau (from The Whale) is strong. There are times when you can see her acting. I like Stephanie Hsu, but she takes a long time to get going, and I spend my time wondering how the actress she replaced (Awkwafina) would have handled the role in Everything, Everything All a Once. Jamie Lee Curtis is transformative, but gets no redemption in the script. Kerry Condon is great in Banshees of Inisherin bringing both depth and empathy, but she gets utterly outclassed by Angela Bassett (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever).

Best Supporting Actor

No one stands out exceptionally in the Best Supporting Actor category. The win will probably go to Brendan Gleeson (The Banshees of Inisherin), who is good, but wins because he has disproportionately more time than three others on the list. The real win should go to Barry Keoghan also from Banshees of Inisherin who plays an utterly convincing dolt with great comic timing. Ke Huy Quan (Everything, Everywhere All at Once) is the leading man, and shouldn’t be relegated to “supporting”. He’s adorable, and he worked very hard for the role, especially in his physical acting, but has so many identifiable idiosyncrasies as a human being, that it is difficult to see past that into what makes his character different. His shortcomings are particularly on display when he is made to play a suave man in a particular universe. Judd Hirsch was charming but bombastic as an uncle in The Fabelmans. Unfortunately, I have not seen Causeway, but Brian Tyree Henry is definitely an actor to watch out for.

Every other category all at once

I have a few more films to watch before weighing in on some of the other categories. With my incomplete research, but just to put a ribbon on it, I’ll quickly wrap the other categories.

I’m going to propose that best score goes to the scarce but haunting cracker of a soundscape from All Quiet on the Western Front.

Best sound design is likely going to The Batman because of choosing many times to be non-diegetic about when to fade out rain, or when to zone into a person’s perspective, rather than sticking to reality.

Best Visual Effects is clearly going to the 10 years in the making Avatar: The Way of Water.

Costume is likely Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, Animated Feature is likely Pinocchio.

I’m not sure why Wakanda Forever does not get nominated for Production Design, so that’s going to Avatar (All Quiet on the Western Front is a strong contender, but because of its thoroughness and veracity, which does not win over bold creativity).

I haven’t seen Living so lacking that Women Talking will probably win Best Adapted Screenplay though it should have gone to The Whale. Everything Everywhere All at Once should rightfully take away Best Original Screenplay.

I’m not sure how much of The Whale is make-up and how much is CG. But if it’s all makeup, they’re going to win Make-up and Hairstyling, even though both All Quiet on the Western Front and Wakanda Forever had to put a great deal more effort into their films.

I haven’t seen two of the films in there for best Cinematography, so I’m going to go with All Quiet on the Western Front because it has a trifle more beauty in it than Tar. Tar’s cinematography is good, but small budget. It’s about as good as the cinematography of a good serial, like let’s say Mr. Robot. Good, but given the context (we live in a time of an extremely high bar of Cinematography), perhaps not good enough.

And lastly, I don’t think anyone will contend if I say Best Editing really has to go to Everything Everywhere All at Once.