My holiday decisions follow the ‘roads less travelled by’. With a long weekend looming in April, I sign up for a short trip to Central Asia, to visit Tashkent and Samarkand.

I know very little about Central Asia except that the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 gave birth to five new republics—Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. I assume that these countries would have had to grapple with deep-rooted memory of the repressive Soviet regime; Muslim majorities and ancient histories; centuries of nomadic life lived on the edge; and the vagaries of being on the silk route. I have learnt that the region is endowed with natural beauty and natural resources, and is self-sufficient in food, with surplus production of cotton, oil, gas and electricity.

To Tashkent!

We get the first glimpse of Uzbekistan even as the four-hour direct flight from Mumbai to Tashkent prepares for take-off. A video delivers the statutory in-flight safety instructions, juxtaposed with the country’s exotic ancient culture. My anticipation builds.

Our hotel, near the Kosmonavtlar metro station, is in the centre of the town. I love meandering, unhurriedly soaking in the sights and the atmosphere. The next morning, the crisp fresh air and the clean roads inspire a walk around the hotel to feel the neighbourhood and get acclimatized. We are near a beautiful public garden, and spring is in full bloom.

Our morning walk through a garden

We come across a bus terminus, and on a sudden impulse, hop on to a bus to catch a bus eye-view of Tashkent. We pass monuments, statues, malls, gardens, universities… We discern three distinct areas of Tashkent:

- The old city with its rich Islamic heritage

- The verdant Russian quarters, with remnants of Russian colonisation

- The new age capital with posh office buildings and government institutions like any metropolitan town.

The Old City

We decide to cover the old city first; it is home to the top three places to see in Tashkent. Our English-speaking guide, Kamola, brings her car to ferry us around and tells us interesting anecdotes about the city and the monuments.

1. Khast Imam Square and Chorsu Bozar

The Khast Imam is a World Heritage site—clean and serene, with a manicured lawn, gravelled pathways and a large brick-paved courtyard that houses three monuments.

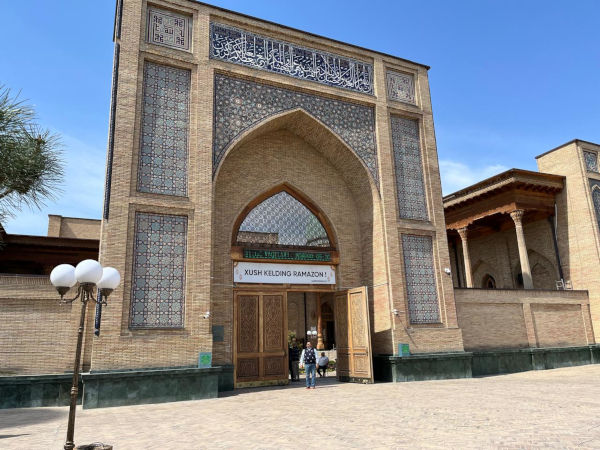

Hazrati Imam Jami (Friday) Mosque

The Hazrati Imam Jami Mosque is the main attraction. It is used for Friday prayers but since this is the holy month of Ramadan, there are groups of visitors. The mosque is so named as it is located near the grave of Hazrati Imam, the first Imam-Khatib of Tashkent—a scientist, an erudite scholar of the Quran who translated the Old Testament (Torah) into Arabic, a poet, and a craftsman adept in the art of making locks and keys. The construction started in the 16th century, but it took a few more centuries to build this beautiful structure. It is now the religious centre of the Muslim Board of Uzbekistan, revered like the Papacy in Rome.

Two 53-meter minarets and two glistening blue domes enhance the majestic beauty of the mosque. It is designed to catch the natural light inside the mosque throughout the day. The imposing sandalwood gates are carved with intricate Uzbek designs of yore and a banner at the entrance announces ‘Xush Kelding, Ramazon!’ signifying special Eid rituals of the Holy Month of Ramadan. It feels good to be inside the prayer hall during the Holy Month and be enveloped by serenity.

We walk on the rich wall-to-wall Persian carpet and admire the grand ceiling adorned with chandeliers and ornate motifs in gold leaf. At a rough guess, about a thousand people can pray at a time. The guide informs us that the mosque has a divine grace—the entire area was miraculously spared during the great earthquake of 1966 that destroyed 80% of Tashkent.

The Hazrati Imam Jami Mosque

The prayer hall at the Hazrati Imam Jami Mosque

Barak Khan Madrasah

Behind the mosque is the 16th century Barak Khan Madrasah, a school with several small classrooms for religious teachings. In olden days, these classrooms were used for small group interactions. I marvel at this centuries old pedagogic practice, which is now considered a “new method” for group discussions in break-out rooms.

The madrasah is now defunct and houses souvenir shops selling Uzbek wooden handicrafts, ceramics and the famous ikat chapans, the long silk or cotton wrap that I see most women wear over Western clothes. Tashkent is known for ikat weave—the dyed thread woven in geometric triangular patters, mostly in a single colour. Instinctively, I find myself comparing it with the ikat from Odisha and its colourful and intricate floral and geometric patterns. Today, designer Uzbek ikat chapans are hitting the international fashion market. I pick up some ikat pouches and a ceramic wall-plate as souvenirs.

The Barak Khan Madrasah. Photo by Ymblanter - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia

An ikat chapan, and a souvenir shop

Moyie Mubarek Library Museum

Kamola is upbeat about taking us to the third monument—a library museum. I have seen libraries but never been to a library museum! We have to pass through high security checks (Kamola negotiates that) before entering the Moyie Mubarek Library Museum—the famous 7th century Quran of Caliph Uthman Ibn Affan is kept here within a glass case, right at the front of the room. We are awestruck by the size of the Holy Book—3 to 4 feet when open. We are told that the 354 parchment sheets (of leather) of the Quran, in Kufic script, were first stored within the Treasury of the Caliph of Baghdad. Centuries later, Sultan Timur (about whom we would learn more at Samarkand) brought them to Samarkand as loot. During the Russian occupation, Russian scientists took it to St Petersburg to test its authenticity but after the October Revolution, Lenin returned it to Tashkent as a goodwill gesture. Since 1924, it has been at the library as a prized possession.

The library is also a treasure house of rare oriental Islamic manuscripts and an array of Qurans in different shapes, sizes, and languages.

If one has just one day in Tashkent, I would recommend a visit to the library and the Hazrati Imam mosque.

Clockwise from top: The ancient Quran, the smallest Quran, and other exhibits

Kamola takes us to another monument, the Minor Mosque—aka the White Mosque because it’s made of white marble—about 2-3 km away. It was opened as recently as 2014. Prayer halls are typically rectangular, but the one at the Minor Mosque is circular with the beautiful mihrab (a niche in the wall that indicates the qibla—the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca) and Islamic carvings.

The Minor Mosque

2. Chorsu Bazaar

From the solemn atmosphere of the mosques, we come to the mundane world of trade and commerce at the Chorsu Bazaar. It is said to be the largest and oldest market in Uzbekistan and one can spot the bright turquoise dome from afar. Inside the double storey market, it is as congested as Crawford market in Mumbai, with shops selling spices, clothes, handicrafts, fresh fruit and vegetables, meat, nuts, saffron…

3. The Farmers’ Market

It’s a little stuffy as there is no cooling, so Kamola drives us to a farmer’s market a little distance away—the Mirobod Dehqon Bozori. It is much smaller, but it’s sunny, clean and better organised. We spend an hour enjoying the market—it has everything that a visitor would want in Tashkent. And, compared to India, the prices are much lower. I bought Iranian saffron at approximately Rs 1,200 for 10 gm.

From left: Chorsu Bazaar; The Mirobod farmer’s market

The Russian Imprint

The next day, on the way to the Russian area, Kamola fills us in on the 150 years of Russian occupation from 1865 to 1991. By and large, the Soviet era is a saga of exploitation. After the Soviet embarrassment in World War II, there were attempts at improvement through investments in heavy industries, but it is seen as communist propaganda for the consumption of the world. Then, the Tashkent earthquake of 1966, which destroyed 80% of the city, provided them another opportunity to manipulate public opinion.

The Monument of Courage

We stop at the intersection of Sharaf Rashidov Street and Abdulla Kadiri street, the epicentre of the earthquake, to see the Monument of Courage dedicated to the resilient spirit of reconstruction. It is a larger-than-life sculpture of an Uzbek man shielding a woman, who in turn is shielding her child from the cracks opening up in the ground. There is a black granite cube at one corner, split by a zigzag crack, one side showing the date (26 April 1966) and the other, a clock frozen at 5:24, the time of the earthquake. Behind the figures is a long metal panel showing cutouts of Russian men and women helping in the reconstruction—the propaganda obvious.

The Monument of Courage

Kamola shares more details about how the Uzbek look and character of the city was wiped out as Tashkent was rebuilt in the image of Soviet architecture, leaving a lasting Russian footprint. Ironically, 20% of the new homes were allotted to the Soviets who stayed back in Tashkent. This changed the demographics the city. There was another consequence of this manipulation: it brought about the intellectual revival of Islam and return to Islamic practices that were undermined during communist rule.

We drive around town locating typical Russian architecture: nine-storey box-like buildings; the Stalinist design of large ornate homes with arched gates; sprawling parks and leafy side roads. We stop to see the iconic Hotel Uzbekistan (1974) on Makhtumkuli Street, the first 5-star hotel in Tashkent that looks like an open book. The style is Modernist Soviet-Uzbek design.

The Hotel Uzbekistan

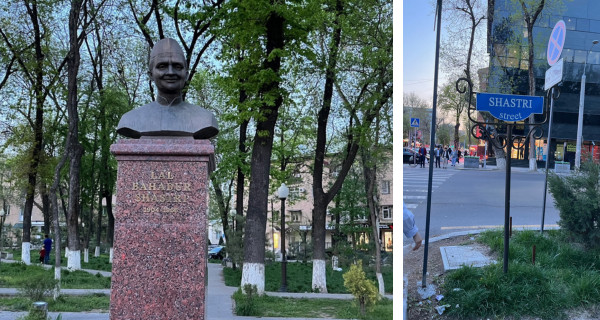

We have a historical memory of Tashkent—the ill-fated Tashkent Agreement between India and Pakistan mediated by the Soviets after the 1965 war, and the sudden death of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri the same night. The monument to Shastri is located on a street named after him: the ‘Shastri Street’. The bust is mounted on a pink pillar. We pay homage to the great leader who gave us the slogan ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ when India needed to focus on agriculture.

Lal Bahadur Shastri’s bust; on Shastri Street

Modern Tashkent

This is the area around Amir Timur Square in Central Tashkent. It houses impressive government buildings and institutions like the Palace of International Forum, Dom Forum, Independence Square, Art Galleries and TV Towers. Almost all buildings carry political narratives connected with the first president of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov. He was elected after the country gained independence in 1991 and stayed in office till his death in 2016.

Karimov is said to have run a repressive authoritarian regime. So, effectively, the Soviet era practices continued. Karimov even ordered the felling of thick rows of Chinar trees around Timur Square so that he could keep an eye on the people in adjacent administrative establishments. Today, most of the buildings can only be viewed from outside. The traffic is regulated, there’s a hush and heavy security, and no casual walkers in the parks and streets.

However, the architecture can still be admired: The imposing columns of the white Palace of International Forum, the glazed facade and Persian motifs, and the sculpture of two pelicans on the dome draw my attention. It is the most representative building of the capital, used for hosting state events. Kamola describes its classy interiors for which no expenses were spared ($1 billion). It is devoid of human movement.

The International Forum Palace

We drive past other important structures: the Dom Forum, a venue for receiving foreign guests; and the Independence Square, a 12-hectare area that houses the Independence Monument, as a symbol of Uzbek sovereignty. A huge globe with an exaggerated map of Uzbekistan is mounted on a pedestal. People gather here to watch the Independence Day parade. Surrounding the Independence Square are the Senate building, Romanov Palace (again closed to the public) and The Crying Mother Monument (1999) where an eternal flame honours the 400,000 Uzbek soldiers killed in WW II. We also drive past the 375-metre-tall TV Tower from where one can get an aerial view of the city.

Back at the hotel, Kamola stays for coffee and I ask her about the absence of people, even youth, from public places. She says most students keep busy with evening classes and the adults need to work two jobs to earn a livelihood. She also mentions a language barrier—the Soviet era had made Russian compulsory but now that they are gone, the four local languages of Central Asia have no common linguistic channel. She hints at a gap between the rulers and the common people leading to a kind of alienation in general. I probe no further.

To the Mountains

After two days in Tashkent, we are excited at the prospect of seeing the beauty of Chimgan Mountains and the Charvak Lake, about 90 km away. It’s a cloudy day and our guide Umaid advises us to bring snacks and a fleece as it is going to be colder on the mountains. I request him for a detour through the countryside so we can see life in a village. As we reach the Suqoq village, I am amazed and delighted to see gas pipeline to all mud houses.

Every village house has piped gas

We stop by to see clusters of small cabins by the gurgling river. This is a resort one can book for family meals, and is much in demand during Ramadan. It is closed during the day as people are on the fast. But we peek inside the cabins to see the Tapchans, the low seating unique to Central Asia, around a table. It can seat 4-8 people and plastic curtains assure some privacy. One can even enjoy a siesta on the large cushions. I am told that a meal can cost between $10 and 20. I wonder if local villagers can afford this place.

From left: A cluster of Tapchan cabins; inside a cabin

We resume the journey and pass vineyards. I notice girls going to school in small groups, without a male escort. We stop at a roadside stall selling fresh ‘samsas’ baked in a gas-fired clay oven—this humble snack must have reached India as samosas.

Samsa being baked in a clay oven

After another hour’s drive we finally reach the Charvak Lake and the Chimgan Mountains. I can only say that the natural beauty of the area is to be seen to be believed. Just breathing in the air laden with the fragrance of peach blossoms is an elixir.

Clockwise from left: Charvak Lake, peach blossoms, and the snow on the mountains

As we go a little higher on the mountains, we see 4-5 inches of snow. This place is popular for skiing during hard winters. Just now, it is off season. As we keep driving, I spot a signage that says ‘Tibet’ and I guess Babur must have known how close India was.

After an invigorating day, we return to Tashkent. Umaid suggests an early dinner at Raaj Kapur, an Indian restaurant at Le Grande Plaza Hotel on Ovozi street. We ask Umaid to join us, and only then come to know that he is on roza, the Ramdan fast!

At the restaurant, the Rajasthani chef offers personalized service. More than the food, what delights us is the wall of celebrities—charcoal drawings of Adi Godrej, S.M. Krishna, Rajnath Sigh, Annu Kapoor, Gulshan Grover and others.

Raaj Kapur restaurant and the Indian Hall of Fame

We finally retire to the hotel to pack and rest. Tomorrow, we take an early morning train to Samarkand.

Train to Samarkand

I must mention that the trains in Uzbekistan are punctual; the train carriages are modern with reclining upholstered seats; the platforms are not crowded as only those with reservations come; and the watchful eyes of the security personnel check the tickets and allow the boarding.

The train journey is part of the ‘things-to-do’ in Uzbekistan. The three-hour ride is yet another chance to watch the countryside as the urban landscape changes to open fields and mud houses connected with yellow gas pipes. I see cotton fields and recall Kamola’s words about how cotton is a sour point for Uzbeks. The Soviet policy pushed for cotton monoculture during the 1960s. It was enforced even at the cost of growing food. By 1988, Uzbekistan had become the world’s largest cotton exporter that fed the Soviet textile mills, but the drop in the water table was irreversible.

I start reading up on Samarkand. The 14th century is said to be the glorious age of Timurid Renaissance under Timur, the founder of Timur dynasty. The nomadic conqueror set the stage for a structured empire. Indians know of Timur who invaded India in 1398, but we are more familiar with his great-great-great grandson Babur who founded the Mughal empire. Timur, primarily regarded as a great and brutal military leader and strategist, was also a patron of art and architecture. I also know of Timur through Christopher Marlowe’s play Tamburlaine the Great. Our Samarkand visit will be a chance to see the footprints of Timur’s legacy in contemporary Samarkand.

Registan Square

We check into the hotel and head out to visit the principal attraction: The Registan Square. We find hordes of people and long queues at the entrance. We need to buy an entry ticket; at an adjacent cubicle, we bargain for an English-speaking guide.

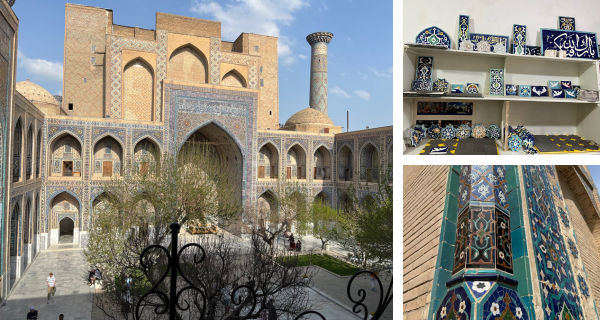

We enter a huge courtyard, and the magnificent monuments take our breath away—pillars and arches covered with glazed bricks and ceramic tiles in bright shades of royal blue, turquoise, white and green with Islamic inscriptions. Built by Timur and his grandson Ulugh Beg, its grandeur is comparable with Rome and Athens. It is said that Timur brought architects, masons and artists from India, Afghanistan, Persia and Arabia to create this masterpiece in the Timurid style.

The complex is home to three madrasahs: the Ulugh Beg Madrasah, the Tilla-Kori Madrasah, and the Sher-Dor Madrasah. The large courtyard in the centre must have been used as a public square.

Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417-1420)

This is a three-storey structure with a rectangular courtyard. The peach trees are in full bloom. There are rows of hujras (cubicles) around the courtyard, meant for small groups learning from the masters. There are no windows in the cubicles! The guide tells us lectures were held by famous scientists and scholars, including Ulugh Beg who encouraged scholarship in astronomy, Theology, philosophy, logic and physics.

Today, the cubicles on the first floor are used as souvenir shops and showrooms for tile making. We watch the fascinating process of cutting intricate geometric patterns on the tiles.

Clockwise from left: The Ulugh Beg Madrasah courtyard, the tiles showroom, and tiles on a pillar

Sher-Dor Madrasah (1619-1636)

Functionally, this madrasah resembles the Ulugh Beg Madrasah, built 200 years earlier, except for the controversial arch gate—it depicts two lions (sher means lion) chasing deer with the human face of sun bearing Mongol features. It depicts the power of the conqueror (lion) and the enlightenment of the mind (the sun). It is controversial because usually, animal and human figures are not allowed in Islamic art.

As we enter, we find a documentary is being filmed with a group of students in period costumes.

The Sher-Dor Madrasah

Tilla-Kori Madrasah and Mosque (1646-1660)

This madrasah has a magnificent gate with intricate patterns in blue and decorative highlights of gold leaf—the art of gilding or tilla-kari. There are classrooms around the large prayer hall; the picture gallery has prints of paintings of old Samarkand.

Registan Square makes me understand two things:

- During the medieval period, education was taken seriously but it was only for the elite.

- I grasp the basic tenets of Islamic design. I noticed them in Tashkent too but it is more evident in Registan Square:

- The concept of light, the noor that illuminates—the mosques capture the sunlight all day long

- The concept of space, symbolizing the void—which can be seen in the large gardens and paved courtyards

- The concept of geometry, signifying latency or the need to manifest that which is invisible. This can be observed in the calligraphy and the abstract floral patterns on the arches, doors, pillars and the ceilings—Islamic designs are devoid of human and animal forms.

We come out of Registan Square with images of splendour and magnificence, and head to the bespoke restaurant Platan for dinner; one needs a reservation but I think our pleading eyes do the trick and we find a table. I can’t recall a meal as sumptuous as this. The plate of grilled chicken has a herby flavour; the salad and soup taste heavenly; and the bread is soft and flavourful. Maybe the fact that we are famished makes the food more appetizing.

Platan restaurant

Our last day in Samarkand happens to be the day of Eid. But unlike India, there is no visible sign of festivities. Several theories cross my mind and I park them till I can cross-check.

Gur-i-Amir

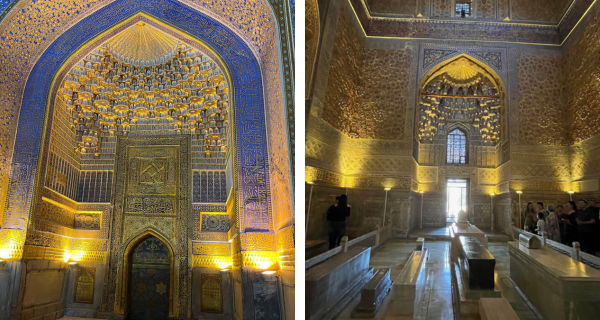

Our plan for the day is to visit the Amir Timur Mausoleum. Samarkand is a small place and everything is close by. We join the hordes of visitors. It is believed that the place has divine benediction and all sincere prayers are answered. We walk around the courtyard, admire the onion-shaped blue dome, and finally enter the family sepulchre of Timur, his two sons, his grandson Ulugh Beg and five others. The actual graves are in the underground crypt. The tombstone on Timur’s grave is the largest piece of dark green nephrite, with supposed magical powers. The inscription in Arabic reads: “When I rise from the dead, the whole world will tremble.” Legend has it that anybody who dares to open Timur’s grave will incur catastrophe. Much against the advice of Elders, a Soviet archaeologist opened the grave on June 19, 1941 and found a second inscription: “Whosoever disturbs my tomb will unleash an invader more terrible than I.” A few days later, Germany attacked USSR.

The Amir Timur Mausoleum: The sepulchre decorations and the grave chamber

One is supposed to sit for some time and offer prayers. There are benches for this purpose. As I too sit down, I admire the opulence and craftsmanship of the grand chamber. The lower portion of the walls is covered with slabs of onyx and the upper part is adorned with murals and decorations. There are alcoves with unique honeycomb shapes (corbels) like the stalactite work, made of papier-mache and decorated with intricate floral designs in blue and gold. Thousands of such pieces are glued together to make an alcove. It is difficult for me to describe the mesmerizing effect of the small corbels clustered geometrically to create the arch.

Outside the grave chamber is an art gallery displaying paintings of Timur seated on a throne. There is a larger-than-life statue of Timur, seated in the same pose, in an island on the intersection.

The Amir Timur Mausoleum: Alcove with papier-mache corbels

We meet a teacher from Pakistan who teaches in a school in Bukhara and a software engineer from Sweden and wish them ‘Eid Mubarak’. A casual chat leads to sharing of observations: I learn that not everyone goes to offer namaz at the Central Mosques; they prefer going to the small neighbourhood mosques that are maintained by the people and not the state.

We decide to try fusion cuisine at the Jumanji restaurant. The ambience is elegant; we settle for a garden table and ask for Khachapuri (a cheese-filled bread), tomato salad with feta cheese and pine nuts, spicy sauteed cucumber salad, soup and a double helping of tiramisu. Everything tastes delicious and we finish off with Georgian coffee. The meal is a fitting finale to the Samarkand trip. We leave for Tashkent next morning.

At jumanji restaurant

We have learnt so many things during this visit, cleared several preconceived notions about the region. I learnt that the nomadic warriors loved art, architecture and gardens in equal measure.

I sign off with a quote from Ahmed Rashid in Resurgence of Central Asia:

“This enormous landscape, these courageous people who have suffered such extraordinary calamities in the past century need time and space to rediscover their own soul.” Amen.

Travel Tips for Uzbekistan

Planning: Research on the following sites: TripAdvisor

- Visa: The process is uncomplicated. Apply for an e-visa and keep a margin of one to two weeks. No visa interview required.

- Book train e-tickets

- Book flight: Google Flight Price Tracker (Uzbek Airways has direct flights to Tashkent from Mumbai)

- Hotel booking: Prefer a good hotel near the metro station or town centre. (Expedia or Hotels.com)

- Daily registration slip from the hotel: even though Lonely Planet mentioned this as a requirement, it is no longer required.

- Walking Tours: In Tashkent, a free walking tour was not reliable. The guide never turned up. You can book a tour on Viator or Guruwalk.

Read: I found Ahmed Rashid’s book, The Resurgence of Central Asia, quite informative. The Baburnama gives Babur’s account of life in Central Asia during 14th century. There is a 30-minute documentary by CNN, ‘The Spirit of Samarkand’.

What to pack: It is a Sunni Muslim country. It is better to be respectful of local culture and blend with the crowd. Carry full trousers and decent tops. Most local women wore the Chapan over trousers and tops.

If you plan a trip to mountains, pack woollens as per temperature. Chimgan Mountains required a fleece and a warm wrap in April.

Invest in a good guide: An English-speaking guide makes all the difference. They are not expensive; Our Tashkent to Chimgan Mountain full day trip including the car and gas cost just $100.

Safety: Contrary to what I had heard, Uzbekistan turned out to be quite safe. However, the usual caution is recommended.

Getting around: Both Tashkent and Samarkand are small towns. One can criss-cross locations several times. Uber is a safe form of transport.

Train travel within Uzbekistan: Uz Rail App for iPhone; Uz Railway app for Android

Shopping: Iranian saffron, pine nuts, dates, ikat Chapan

Recommended restaurants:

- Samarkand: Jumanji, Platan

- Tashkent: The Host, Raaj Kapur, National Food, Shalimar restaurant, Afsona