[From Unsplash]

My dear Viren,

August 15 this year is the 75th anniversary of India’s independence. It is also my 79th birthday and I know you will wish me well as you always do.

I am writing to you about India (which is also called Bharat in our Constitution). India is an incredibly diverse nation that dared to be a constitutional democracy, amidst doubts in the last century about whether democratic governance was a good idea for a poor country. Some people continue to speculate whether India should have been ruled more autocratically until it became rich, like China, our large and competing Asian neighbour.

Seventy-five years after Independence we are far from our “tryst with destiny”, which Jawaharlal Nehru, our first Prime Minister, had declared when he unfurled new India’s tricolour flag on August 15, 1947. Celebrating India’s many achievements since then—in the IT industry, in space technology, in movies and cricket too, and with the numbers of Indian unicorns and billionaires increasing fast, we often forget that India is still a poor country where millions of Indians are still struggling to earn decent livelihoods.

It takes a young child to tell an emperor dressed in his finery that he is not wearing any clothes. You woke me up to how “people like us” in India were no longer noticing the poor people living right around us.

You were five years old. You were visiting us with your parents from the US where you were born. Your grandmother and I moved to the US in 1989 to keep the family together when your father went to college in the US, and also your aunt—his sister. My employer in India, the Tata group, with whom I had worked for 25 years, graciously gave me a long sabbatical. They felt it would be good for me to be with my family, as well as to hone my knowledge of business management. Until the 1990s, India was a “closed” economy, and business interactions between India and the rest were limited. I worked in the US with an international consulting company on assignments with its clients in the US, Europe, and South and North America. I returned to India in 2000 as chairman (India) of the Boston Consulting Group which had recently set up in India to bring Western management practices to Indian companies.

I was proudly driving you, my first grandchild, around New Delhi to show you the sights of our capital city. We drove up to the Rashtrapati Bhavan, the imposing residence of our President which used to be the British Viceroy’s palace. We drove along the open central vista stretching from it with the Indian ‘arch of triumph’ in its middle. Viren, I am sending you a photo to remind you of the good times we had together.

India had changed a lot since your father was a five-year-old child in India in the 1970s. Then we drove around either in a clunky Ambassador or a tiny Fiat, the only two models of cars available in India. Those cars were not airconditioned and we had to drive with their windows down. Wherever we had to stop in traffic, beggars would put their hands through the open windows beseeching us for alms. Now there were more cars on the roads and modern ones. I was driving you in a large, airconditioned Toyota sedan amidst Hondas, Suzukis, Mercedes, and BMWs, all airconditioned with windows up. I strained to show you any Ambassadors or Fiats to explain to you what India was like when your father was your age.

We stopped at a traffic light not far from Rashtrapati Bhavan. When we drove on you asked why no one in our car had answered the knocking on the window. Busy talking amongst ourselves, we had not heard any. You said a lady, with a child in her arms, had been knocking on our car window and we had not answered. You wanted to know why families were cooking and eating on the roadside. Had we not noticed, you asked? Your mother explained that many Indians are very poor, they hardly earn, and cannot afford decent shelters.

Seeing is believing: don’t trust just numbers

Two years later, on your next visit, when you were seven, I had been appointed a member of India’s Planning Commission. We were driving through the same area. Looking out of the car window, you exploded in indignation. “What’s the government doing? Counting daisies?” you asked. Startled, I asked, what you meant. “Look at how many poor people there are,” you said, pointing to families huddled unsheltered on the roadside amidst their pithy possessions.

At that time, unknown to you of course, the Planning Commission was explaining the reduction of poverty in India with charts of the numbers of people who, since India’s independence, had crossed a mathematical poverty line defined by an economist. With your child-like innocence you saw things as they are. It was a lesson for policymakers. Economists’ numbers can never represent reality fully or accurately. One must go to the “real place”, look at “real things”, and talk to “real people” to understand what life is really like for them.

Compassion

The lesson you gave, Viren, was compassion for those who have much less than we have. This was the talisman Mahatma Gandhi had given to all leaders. Whenever you make a policy or take a decision, think of how it will improve the life of the poorest person you know, he said.

I brought you to the Planning Commission’s offices in my government car with the red beacon atop and a flag-post in front to fly the national flag. I wanted to impress you. You enjoyed the ride and saluted all the guards who saluted you when we passed. You liked my large office, where the staff spoiled the member’s grandson with more sodas and biscuits than were good for you.

Listening

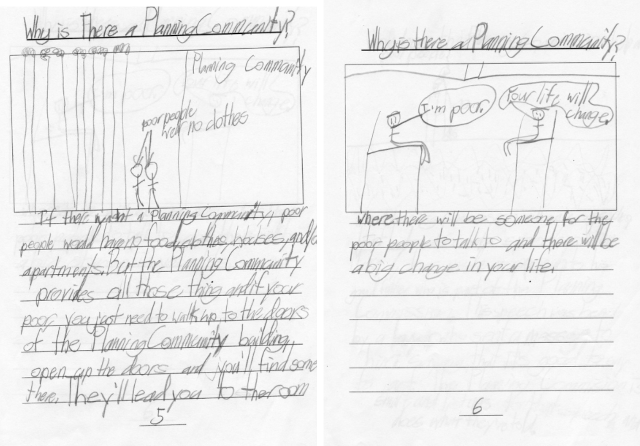

You revealed your literary talents soon after. Your class in school back in the US was asked to write an essay on what they had learned in their holidays. You produced an illustrated book on the Planning Commission of India. You may have forgotten what you wrote. I am reproducing a page from it in which, referring to the Planning Commission, you say that the “Planning Community is a place where all the poor people of India can come, and there will be someone to listen to them, and then they will not be poor anymore.” I was struck by your transformation of the “Commission” into a “Community”!

(From Viren's "book")

People are not numbers; they are human beings. Your advice to policymakers was that “people like us” must listen to “people not like us”, not only to hear their knocking on the windows of our privileged lives, but also to understand their perspectives, and, above all, by listening to them giving them the dignity they deserve as equal human beings.

What sort of world are we leaving for our grandchildren?

The world is in bad shape. Poverty persists everywhere, even in the US. Inequality between the few who have a lot and the rest who do not have enough is widening. During the Covid pandemic, while billions around the world struggled to keep their lives together, stock markets boomed, and the wealthiest people became even wealthier. The footprint of unbridled human progress on the planet has become unbearable. Nature is reacting. People in poorer countries have been suffering for decades from depletion of their water sources and degradation of their soils and forests. Enormous fires and floods have ravaged even the rich United States in the West and Australia in the East.

It has become a cliche to ask grandparents what sort of world we are leaving for our grandchildren. Many older persons are realising that we do not have the solutions required. In fact, it is our ways of thinking and doing that have created the problems that now need to be solved with new thinking and much faster too. As Albert Einstein said, it is madness to try to solve intractable problems with the same thinking that has caused them. Therefore, we must leave it to our grandchildren to create the world they want to live in. It is essential, of course, that they apply fundamentally new ways of thinking and working, and not just apply, with their more youthful energy, the ways they have learned from us. Because then we will all fall off the cliff even faster!

Life-long learning

All over the world, even in poorer countries like India, people are living longer than they used to. Increasing longevity is a benefit of technological and economic progress. Already the number of older persons, over 65 years, in the world exceeds the number of children below 5 years, and soon will exceed the number of children below 10. While power must shift towards younger generations, older persons (like myself!) must not be considered as burdens to be cast aside. Older persons could be humanity’s fastest growing though least used resource. Generations are stages in a larger process of human evolution. All generations must work together. Inter-generational dialogue is imperative. All must listen to others’ aspirations and build on others’ knowledge.

You are interested in the biological sciences, and you may be exploring them with other subjects when you begin in the University of Chicago this year. You may encounter the concept of “neoteny” which the biologist Stuart Kaufmann introduced to the evolutionary sciences. Neoteny—a Greek word—means holding onto youthfulness. Kaufmann shows how those species in which young people stay in the learning mode longer become smarter than other species. Within human societies too, more young people go into higher education in “developed” countries, while in poorer countries they must begin to work and earn much sooner, sometimes even as children.

My mother, your great-grandmother, who died three years ago, lived until she was 97. After she turned 90, she said she no longer wanted to add years to her life: she wanted to add life to her years. She said living is a process of learning. When one stops learning, life is no longer fun. She remained curious until the end of her life. I hope you will retain your compassion for others, and your curiosity, all your life; and that you will keep asking why the world works the way it does, and you will keep looking for new insights and fresh solutions.

However, like you had urged me to, you must soon “do” something to make the world better for less fortunate people. Therefore, you must become a life-longer learner in action as Gandhiji was. His own life story, as you know, is called “The Story of My Experiments with Truth”.

I don’t need to tell you about Gandhiji. In fact, you had discovered him yourself. When you were learning how to write poetry in school, you were asked to read the biography of a great person you admire and then write poems about this person in different poetry forms. We are living in the STEM age: the age of science, technology, engineering, and math. Unsurprisingly, you wanted to write about Albert Einstein, the greatest scientist of the last century. However, when you went to Barnes and Noble to buy a biography of Einstein, you showed up at the check-out counter, where your father was waiting to pay, with a biography of Mahatma Gandhi instead. You explained to your father that you admired Gandhi also, and since the biography of Einstein in the bookshop was very fat, whereas Gandhi’s was slimmer, you had decided to save yourself time in your assignment and your father some money!

Turning towards the path not taken

While you continued your education in school after writing your book about India’s Planning Commission, I began to think harder about why India was not reaching its “Poorna Swaraj”—full freedom that is, when all Indians will have political freedom, social freedom, and economic freedom—which was Gandhiji’s goal.

A goal without a path to reach it, is like a castle in the air. Gandhiji had a vision of the journey to reach the goal. Genuine democracy is government of the people, for the people, and by the people too. In Gandhiji’s vision, citizens would govern their communities in their villages and cities. Plans for improving their own local commons would be cooperatively developed by the people themselves, not imposed on them by planners afar from them.

Gandhiji’s vision of local democratic governance was ahead of its times. It was dismissed as romantic. In the middle of the last century, when India became independent, central planning was the fashion everywhere. Central planners repaired war-torn European economies; they built the Soviet Union into a mighty industrial machine; and in Japan, MITI (ministry of international trade and industry) planned the rebuilding and growth of Japanese industries.

India had a larger gap of modernity to bridge with less resources, and therefore Nehru adopted the same model for India. Local self-governance remained a dream in the Constitution, while the country marched ahead building large dams and large factories, and it adopted large-scale farming with industrial inputs. Parts of India marched ahead. Bharat—the India that lives in its villages—was neglected. Poor people from rural India kept flowing into cities seeking some livelihoods—like the people you heard knocking on the window of our car. Sadly, the cities were not able to provide them adequate livelihoods and decent living conditions and overcrowded Indian cities became sprawling slums. Overwhelmed planners and experts at the Centre floundered amidst their spreadsheets of numbers—"counting daisies” as you said. They were not listening to the people on the ground.

Like the rest of the world, we adopted mass production methods. Gandhi said that, rather than “production for the masses”, he preferred “production by the masses”. His model would generate more incomes in small enterprises that produce for each other. Whereas mass production enterprises concentrate wealth and power in a few people. With more mechanisation of production in the large factories, jobs become fewer. With fewer jobs and people not earning enough, demand for products reduces, and capitalists become reluctant to invest any more. Thus, economic growth slows, as India’s seems to have. India needs to create many more jobs for its large youthful population. Therefore, India urgently needs a new solution.

When I had returned to India in 2000, I had heard “the knocking on the window” in Mumbai, which you heard when you were driving through New Delhi eight years later. The beggars swarmed around cars at traffic lights and tried to attract the attention of the people inside who, in airconditioned comfort, listened to music and conversed with their friends on cellphones which were becoming ubiquitous—another sign of India’s progress.

Other citizens were also concerned about the persistence of inequality and poverty in Bharat (that is India) amidst signs of “India shining” for the well-off. Therefore, diverse Indians from many walks of life—business leaders, academics, schoolteachers, farmers, social workers, etc.—put their heads and hearts together in a structured process of “generative scenario thinking” to understand what was preventing faster all-round progress of the country. I had learned this process while consulting in the US and was asked to facilitate it.

The questions we asked ourselves were:

- What must change in our approach to transformation of the economy?

- What sort of leaders are required?

We uncovered the underlying “theory-in-use” that was driving change. Which was top-down management. But we did notice another, bottom-up theory-of change emerging.

Hopes of change

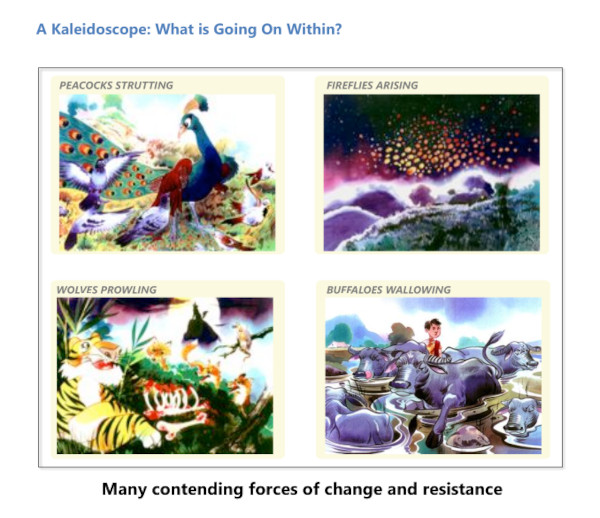

Many young people participated in the process. A young woman, an artist, described what we learned in pictures. A picture can reveal more than a thousand words can and much more than tables of numbers.

Four pictures of the theory of change and leadership emerged. One was a picture of top-down management of change by government planners. In this picture, the big leaders on top were depicted as buffaloes wallowing in a pond, unable to coordinate with each other, while children waited outside to be able to get access to clean water and more nutrition and a better education.

In the second picture, the leaders were depicted as peacocks strutting around in their finery while little birds scrambled to get access to the grain scattered around the peacocks. This was a depiction of the free-market, capitalist process in action. While the peacocks flourish, the little birds wait for the “trickle down” of opportunities for them.

The third picture showed a tiger growling in the forest with little squirrels and rabbits running for cover. It depicted a strong, authoritarian leader—the king of the forest. In this theory of change, strong leaders are required to impose order into chaotic systems, even with brutal force if necessary.

In all three models of change and leadership we saw operating simultaneously around us, leaders are those on top—of governments, political parties, armed forces, and large corporations. In all three models, the little people are either ignored or squashed. Not a pretty picture, which gave little hope for faster inclusion in the benefits of growth for most Indian citizens.

However, there was a fourth picture. This was a picture of fireflies arising in the darkness. Fireflies are tiny creatures who carry their own light and inspire others. We had found in our search of India many examples of young and older people in different parts of the country who were catalysts of change in their communities. They were improving the management of local water resources, improving the local school, working in cooperative enterprises and self-help groups. They were inspiring their communities to marshal whatever resources were available to them for their collective benefit. Thus, they were bringing about change in what mattered to the people.

This vision has inspired me. Whenever young people ask me now for advice on how they can make a difference to the world until they become the CEO of a corporation or a senior functionary in government, I say they do not have to wait. They can begin leading change right now. They must look around, listen to people around them, and understand what matters to them. Their leadership lies in their will to take steps, even tiny ones, here and now, to make a difference to the lives of others.

The models of change and leadership that the generative scenario thinking process revealed in 2000 have stayed with me. When the Planning Commission, of which I was a member, was preparing the 12th Five Year Plan, we continued using our old methods of top-down, number-driven planning. It is difficult to change the course of a big ship: it has too much inertia.

The Planning Commission decided to experiment with a new approach to planning alongside the conventional approach. In governments and large companies too, plans are generally made in functional silos; whether they are plans to improve marketing, or operations, or financial management in companies; or plans to improve cities, rural areas, education systems, trade systems, etc. in governments. They are made by specialists in their functions and integrated at the top. Alongside the main plan, we also applied a different approach of systems thinking-based scenario planning. In this method one can foresee effects that changes in parts of systems have on each other. Thus, one can nudge all parts to coordinate with each other and progress together. One can anticipate the risks of fixes that will backfire, with their unintended consequences for the whole economy.

Diverse perspectives must be combined, and many “people not like us” listened to, to understand the shape of the whole system. Therefore, we invited diverse civil society organisations, associations of industries, and experts, to participate in the building of scenarios of India’s future. We asked ourselves, “What If” we adopted another, more Gandhian, path than the one we were on? What would be the outcomes in terms of economic inclusion, environmental sustainability, and overall economic growth? A national economics’ think-tank put numbers to our scenarios.

The results were revealing. We found that if we changed the prevalent “theories-in-use” of economic progress, which were top-down, and expert-driven, and which favoured large-scale enterprises, to a more people-centred, community-driven approach, in which small enterprises flourish, not only is inclusion in growth much quicker, but it is environmentally more sustainable, and overall growth is faster too. If we adopt this approach, people in Bharat’s villages will be better off and you will also hear less knocking on the windows of cars in India’s cities in a few years!

The Planning Commission produced a small booklet which explained the scenarios of India’s future if we would take the Gandhian Road less travelled by so far. It has pictures too, like your evocative little book about the Planning Community of India had. The Planning Commission’s fresh scenarios sadly got buried beneath a massive, conventional, plan document filled with statistics. I am reproducing just the cover of the booklet for you here, with pictures of the three alternative scenarios. The document is included in my book, A Billion Fireflies: Critical Conversations to Shape a New Post-pandemic World. Your father may have a copy of it on his bookshelf. I will be happy to send you a copy of your own if you like. Let me know.

(The Planning Commission's booklet explaining the scenarios of India’s future. Click on the image to access it.)

Leaders of change

In the best scenario for India, the nation’s leaders are everywhere. They are not only those sitting on top of governments and large enterprises. They are also many young people in urban and rural areas, who live by Gandhiji’s motto: “Be the change you want to see in the world”. Like Gandhi, they take the first steps towards something they deeply care about and in ways that others around them wish to follow.

After retiring from the Planning Commission in 2014, I have been following bottom-up change-makers in India and around the world too. They are not waiting for their elders to teach them new ways to improve the world. They are learning themselves how to make change in new ways.

Many young Indians are becoming successful business entrepreneurs. Some have even emerged quickly as “unicorns” whose ventures are valued at over a billion dollars by the stock markets. However, I will give you two examples of fireflies who are having social impact and who are teaching young Indians how to become leaders of social change.

My young friends, Prakhar Bhartiya and Hemakshi Meghani, have patiently got an Indian School for Democracy going on a shoe-string budget. Prakhar and Hemakshi are both graduates of public policy programmes at Columbia and Harvard, who had worked as teachers in schools in poor neighbourhoods with the Teach for India programme. Working through the pandemic, they have built an “action-learning” school for young Indians to become better leaders of social and political change in their communities.

Priya Krishnamurthy and her volunteer teachers in CMCA (Children’s Movement for Civic Awareness)—mothers and some grandmothers themselves—have been working for many years in schools in South India, providing modules for students to learn how to be leaders of change. Their programme has deepened over the years. Now, their young alumni, only recently out of school themselves, are becoming teachers to younger students in schools. Thus, the impact is multiplying without need for large infusions of money in the programme.

Such leaders of change—old ones and young ones—are like fireflies, each carrying their own inner light. Leading in small circles of change, they bring hope amidst darkness. They are nurturing swarms of fireflies of young people who, working together and learning together, are sparking movements for change in the wider world.

I know you will become a leader of change in the world in whatever field you work in, and wherever you are. You have the spark in you. Let me remind you of the poem you had written in your school assignment, when you were 12.

Gandhi’s Path to Greatness

By Viren Maira

Date 2/27/16

Don’t let wrong overtake you

Always put up a fight

Never stray away from what you believe is true

Never lose faith no matter what you do

Always battle with all your might

Don’t let wrong overtake you

Let everyone join no matter who

Fight, fight, fight through the night

Never stray away from what you believe is true

The battle must be won with more people than two

You must climb the mountain no matter what the height

Don’t let wrong overtake you

Your mission is completed so take in the view

Because once you scale the mountain and fight the fight, you will see a beautiful sight

Never stray away from what you believe is true

You will see the world as if it’s new

Stand up for what’s right

Don’t let wrong overtake you

Never stray away from what you believe is true

Lots of love for you,

Dadaji