[U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Erica Bechard, via Flickr. CC By 2.0 Deed]

The answers to the two questions are: no and no. The US is not in strategic retreat and a rising China does not have the capability to dominate this space for the foreseeable future. The region from Djibouti to the Solomon Islands is a huge space, and the US has commitments right across the world. It will sustain these in the face of growing Chinese power. On the other side, China has significant weaknesses and limitations. The rise of China is real and cannot be discounted, but US power is not in retreat.

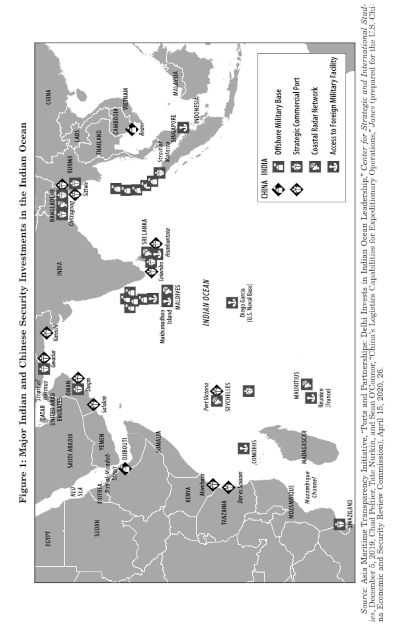

China’s strategic presence in the region includes a naval base in Djibouti, possible access to Pakistan’s Gwadar port (which is operated by a Chinese company), the lease of Hambantota port in Sri Lanka and Kyaukpyu port in Myanmar, and use of Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base. In addition, China’s role in Afghanistan has increased since the US’ departure. This role is primarily economic and relates to the extraction of various metals and hydrocarbons. In the Solomon Islands, China is attempting to increase its influence and presence by building infrastructure, improving the island’s police force, and providing financial aid. Some fear that the islands could eventually give China basing rights.

[Source: uscc.gov]

Chinese military moves in the Indian Ocean and larger Indo-Pacific coupled with US involvement in several conflicts—in Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia, above all—and its relative economic decline has suggested that the US is in strategic retreat and that China will be rampant. This is questionable for at least three reasons: the vulnerability of China’s overseas naval presence; geography; and overall US power, economic and military.

First, China’s naval capabilities and assets overseas are growing impressively, but a combination of American and Indian naval and air power would be devastating to Chinese ships and aircraft in Djibouti, Gwadar (if Pakistan allows use of Gwadar as a military facility—which is not a given), Hambantota, and Kyaukpyu. The US’ Central Command and India’s navy and air force operating from its west coast as well as the US’ Indo-Pacific Command and India’s naval-plus-air power from its east coast would mount fearsome attacks against Chinese assets from Djibouti to the Bay of Bengal. So also Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base would be extremely vulnerable to the US’s Indo-Pacific Command (with the Japanese and Australian navies able to provide support). In short, China’s actual and potential naval bases are highly vulnerable.

Second, geography works against the Chinese navy. The sailing distances for the PLA Navy (PLAN), from home base to the overseas facilities, are enormous. To get to the Gulf and eastern Africa will require PLAN to cross the Malacca and other straits in Southeast Asia, transit the Bay of Bengal and past the Indian peninsula, and navigate the Arabian Sea and Gulfs of Oman and Aden. From Hainan, it would take Chinese aircraft carriers about ten days to get to Djibouti, allowing plenty of time for Indian interdiction from naval bases in Vizag, Kochi, or Mumbai and the air bases of Southern Air Command. Getting to Kyaukpyu would be about three days sailing from Hainan, and PLAN would once again be vulnerable to the Indian navy and air force. From Hainan to the Solomon Islands is five days sailing, and PLAN once again would be open to interdiction by regional navies including the US and its allies.

The other, even more challenging geographical problem for PLAN is that it has only one coastline, and US bases are located nearby in Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. China already has more major ships than the US, but these ships must be able to exit safely from their bases onto the high seas. The US and its regional allies—especially Japan and possibly Australia (less likely Korea)—will be arrayed against PLAN’s egress. They will use not just regular naval and air firepower but also barrages of cruise and other missiles to attack Chinese bases and support infrastructure. Add to all this the fact that the Chinese navy is untested. Its last great era was under Admiral Zheng He who died in the early 15th century. Its current force can intimidate the Philippines and Vietnamese navy; it is quite another thing for PLAN to fight the US and Japanese navies. This is a key reason that Beijing is unlikely to mount an invasion of Taiwan any time soon (unless Taipei declares independence, in which case, win or lose, it will have to attack).

Thirdly, the US still has enormous capabilities, both economic and military. Its nominal GDP is $25 trillion, one quarter of global GDP (the same proportion as in 1980). The US, EU, Japan, Canada, and Australia have a combined GDP of about $50 trillion (China’s GDP is $19 trillion). At the same time, American military power in the Indo-Pacific is formidable: the US Congressional Research Service report of 2023 notes that the US has 66 “defence entities” in the region and nearly 400,000 defence personnel. Its military budget is three times China’s, 40 percent of world military spending, and equal to the outlays of the next ten big spenders including China. There is no sign that the budget will be radically cut.

Finally, China’s role in the two “bookends” of the region, namely, Afghanistan and the Solomon Islands are modest and have been largely overstated by media reports and strategic commentators in the West. Chinese mining and hydrocarbon interests in Afghanistan are quite modest. The biggest problem is prospecting in a country that faces huge governance challenges including corruption. More importantly, as the Chinese have discovered in Pakistan, Islamic extremists (especially Islamic State Khorasan Province) undermine political stability and do not necessarily take kindly to China given Beijing’s treatment of Uighurs and other Muslim minorities. Chinese influence in Afghanistan is therefore limited, and if anything, its economic role is defensive—Beijing’s main worry is ensuring that Islamic extremism in Afghanistan does not spread to Xinjiang and Central Asia, and in this sense its goals run parallel to those of the US and its allies as well as India. In any case, it is likely to have its hands full if it does get more involved in Afghan affairs.

At the other end of the region, China’s investments and role in the Solomon Islands are quite modest and are restricted to building infrastructure, giving some financial aid, and providing military and other support to the island’s police force. As part of military support, Chinese ships and personnel can reportedly be deployed in the islands. While China may have larger strategic goals (disrupting Australian and US influence), it is worth remembering that the Solomon Islands have been wracked by anti-China protests, including rioting against the Chinese community in 2006 and 2021. In 2006, the riots were related to rumours of Taiwanese or mainland Chinese involvement in the island’s electoral politics. In 2021, the violence was sparked by the government’s decision to switch its diplomatic ties from Taiwan to the mainland. China’s interests are therefore also related to the safety of the overseas Chinese. In the midst of political instability and the divide in the islands over relations with China—plus the opposition of Australia, New Zealand, and the US to a larger Chinese role—it is hard to imagine that Beijing can go much further than it has already. As for building a base there, the facility would be highly vulnerable to Australian and US military power.

In sum, a rising China is far from being rampant in this super region, and US power and deployments (as well as the power and deployments of countries such as India and Australia) seriously complicate Chinese efforts at increasing its strategic footprint. The only thing that can change the current pattern of US deployments is if its domestic politics, say, under a second Trump administration, causes America to turn inwards and reduce its commitments from the Gulf to Japan. That would arise from a much larger internal political shift in the US, one that is sociological and political in nature and not a function of economic or strategic exhaustion.

Dig Deeper

1. The U.S.-China Strategic Competition in the Pacific: Something ASEAN Needs to Watch | Fulcrum

2. Is a stable Afghanistan where China, Russia and the US cooperate? | The Interpreter

3. Report on U.S.-China Competition in East, South China Sea | USNI News

4. Geostrategic Competition for Military Basing in the Indian Ocean Region | Brookings (PDF)

The next question in this series:

A string of coups, a tsunami of economic devastation, spurred on by an insatiable appetite for rare earth metals, is changing the political and economic calculus across Africa. Is Africa swapping out Europe for China?

On Wednesday, December 20, we will publish Vivek Y Kelkar’s take. He is a Co-founder of The Cosmopolitan Globalist, an international current affairs online magazine.