[Photo from Unsplash]

I’ve spent part of my career building maps, yet, when asked for directions, I still instinctively think like my grandmother did: “Turn left at the temple, then look for a shop with blue shutters.”

That contrast—between the maps in my hands and the mental maps I actually used—drew me into mapping as a career.

In 2007, GPS in India wasn’t just new—it felt like science fiction to most people. Few had ever seen live maps outside of international news or Hollywood films. At Motorola, I helped launch one of India’s first navigation-enabled phones, years before Google Maps became common. Selling navigation then wasn’t about competing with paper maps. It was about asking people to abandon something older and more trusted: collective memory. Why rely on a blinking dot when the local paanwala could say, “Go past the old neem tree, then ask for Mohan’s house”?

The phones stayed on shelves, their screens dark under shop counters. India wasn’t yet ready to trade a human guide for a digital one. It was my first lesson in adoption: the fiercest competition for new technology is rarely another product. It’s the habit people already trust.

That lesson followed me when I joined MapmyIndia, one of India’s first digital mapping companies. Mapping the country wasn’t a desk job. I ran field surveys, charted bus stops, and even had to pull data collectors out of police stations when company guards mistook them for trespassers.

Even after the data was gathered, selling navigation meant reading each city differently. Car owners in Delhi wanted to avoid rolling down their windows in the blazing heat just to ask for directions. In Mumbai, drivers loved a feature that could predict an Estimated Time of Arrival in their cars—something they’d long relied on instinctively during train travel. In Bangalore, the pitch was simple: avoid the narrow streets where cars could get stuck for hours. The same product had to become three different solutions before anyone would even consider using it.

When we sold navigation devices, the first thing customers did was not to explore new places—they tested the directions for their daily commute, office to home and back. It was their way of asking: Can I trust this machine? Only when the route matched what they already knew would they risk using it for unfamiliar journeys. It taught me something about how to sell technology: even novel products need familiar anchors, or they remain curiosities rather than essentials.

I also learned that mapping is a constant work-in-progress. Building maps in India meant constantly chasing change—roads blocked overnight, slums turning to suburbs, landmarks fading into memory. The maps we built were outdated almost as soon as they were drawn. Highways could be mapped using satellite images, but towns demanded old-school legwork, with surveyors knocking on establishment doors and collecting data points by hand.

[An old map of Madras, now Chennai. Of interest only from history's point of view. Via Wikimedia]

Even now, with LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) helping map cities, remote areas still demand human persistence. You’ve probably seen those cars with odd rigs on their roofs, bristling with cameras pointing in every direction. Those setups use LiDAR—laser-based scanning that builds detailed 3D models of streets and buildings. It’s the same technology helping power future self-driving cars, and it makes urban maps far more accurate. But outside cities, where roads shift and landmarks are unmarked, it still comes down to locals—the dhaba owner, the trucker network, and sometimes, even secret brotherhoods—to point the way where GPS can’t.

Looking back, I couldn’t have imagined that one day, AI would soon let us stitch these maps into living histories—layering not just streets and landmarks, but memory, culture, and power.

By 2010, I was at Nokia, building global-scale location services for first-time users across the countries of the Global South. Western countries had already moved to in-dash navigation and smartphones, but in much of the Global South, location services were still transitional. They weren’t yet about turn-by-turn directions as many of our target users didn’t own cars; they were about helping people find places and orient themselves with landmarks, echoing the offline habit of asking, “Where’s the nearest hospital?” or “How do I get to that temple?” For many, especially women who rarely ventured beyond familiar neighbourhoods, maps became a quiet enabler—opening up new parts of their cities without the discomfort of asking strangers for help.

[For many, especially women who rarely ventured beyond familiar neighbourhoods, maps became a quiet enabler. Image: Pixabay]

Working on maps showed me how they opened doors in the present—and made me curious about how they had shaped the past. By day I helped people navigate their cities; by night I followed the Silk Road from Persia to Samarkand to Xi’an, tracing the paths of merchants, armies, and ideas. That curiosity led me to see maps differently: not just as tools for exploration, but as quiet records of power, each line revealing who controlled what—and who was erased. And once you see maps that way, history itself starts to read differently.

From terrain to trade: how geography wrote our past

Seen through that lens, maps stop being static references and become narratives. Wars, trade, and migrations don’t just happen on them—they follow the contours of land, turning rivers, valleys, and passes into the real drivers of history. Economies thrived when someone recognized the value of a mountain pass or port. The Khyber Pass, a thin line on a map, has funneled Macedonian armies, Mughal caravans, and NATO supply trucks alike, showing how geography scripts history’s repeating patterns.

And yet history is usually taught as a series of dates, stripped of the geographic forces behind it. We memorize the Battle of Plassey’s date but forget how Clive’s cannons, sheltered from the monsoon, dominated the sodden battlefield against an army that didn’t account for the rains. We analyze treaties without seeing how rivers shaped their clauses. We are astonished at Genghis Khan’s conquests but overlook how the steppe’s grasslands turbocharged his cavalry. We recount Rajendra Chola’s conquests but miss their logic. His eastern campaigns weren’t just battles; they were supply chains. Fertile deltas fed armies; ports launched ships toward the Srivijaya empire.

This flattening of history—where terrain becomes backdrop rather than protagonist—is why most children end up hating history.

Maps restore what textbooks flatten, turning abstract timelines into vivid stories of human ambition and terrain's unyielding grip. And just as maps can animate history, new tools now let us do it at scale—turning static timelines into powerful, interactive stories.

When I began exploring LLMs, I realized they could finally merge maps with historical narrative in ways I'd long imagined. I planned to build a tool I had envisioned for years: a layered tapestry of maps and timelines showing how civilizations and events intersect. But I did my research first, and projects like these already exist.

Enter AI: tools that restore layered memory

I found Chronas, an open-source project that shows how empires grew and contracted, and which powers coexisted at any given time. Chronas feels like watching empires play 4D chess across continents—you can track the Ottomans rising as the Golden Hordes of the Mongol empire retreated, see the Ming dynasty thriving as European powers slowly spread, and trace how the kingdom of Vijayanagar overlapped with these global shifts. Watching these changes challenges the idea that our moment is exceptional. Every century, people believed they were central, yet maps show how quickly borders and influence shift.

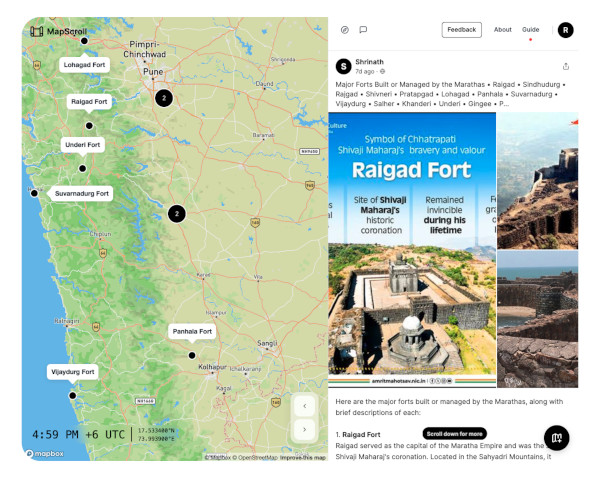

I also came across Mapscroll, which solves another problem: how to plot key locations tied to a theme quickly. Mapscroll is Google Maps meets a history professor—type ‘Chola temples’ and watch history geotag itself—dots blooming with stories and images. It uses LLMs to let you search for elements like “major stepwells of Gujarat and Rajasthan” and maps them with context. It isn’t perfect—at one point it misattributed the Kailasa Temple at Ellora to the Chalukyas, though it was built by the Rashtrakutas in Chalukyan style—but it’s effective for exploration.

Using tools like these, I recently plotted 15 forts associated with the Marathas, including Raigadh, Singhgadh, Shivneri, and Gingee. Seeing their spread revealed patterns in strategic choices and influence that lists don’t convey. Layered with trade routes, rivers, or borders of the era, the map becomes a narrative.

[Screen shot of 15 forts mapped on Mapscroll]

Maps once helped armies and empires. Today, they keep entire cities humming. They do far more than get us from point A to point B. They’re the invisible scaffolding for how cities function and how businesses make decisions. Food delivery apps rely on them to time orders down to the minute, predicting which roads will bottleneck at lunch hour. Retailers use them to study where their device stores should open, overlaying foot traffic with income data. Advertisers sift through geotagged data to decide which neighbourhoods justify the next billboard or hyperlocal campaign. Even city planners lean on maps to spot gaps in public transport, manage waste collection, and plan where to extend power lines. The modern map isn’t just a guide; it’s a quiet operating system beneath urban life—unnoticed when it works, impossible to ignore when it doesn’t.

What maps could become: from static to living histories

The next generation of maps will go far beyond tracing empires and battles. They’ll help us experience the full texture of how humans have lived, built, and imagined their worlds.

Maps might surface stories and cultural memory tied to the places we stand. At Lonar Lake in Maharashtra, a map might reveal a 6th-century temple submerged by rising lake waters, British-era geological surveys debating whether its origins are volcanic or meteoric, and a folk song about the lake’s supposed healing powers—tracing how myth, science, and local memory shape a single landscape.

[Technology promises to map new terrains such as the ocean]

A grandmother in Mumbai might show her grandkids the bustling markets of her youth, now replaced by skyscrapers, using an AR app on her tablet. She might overlay old photos and memories onto the modern cityscape, bringing her stories to life for the next generation.

History buffs might trace the movement of ideas and people: the routes of Sufi saints and Buddhist monks, the travels of reformers and rulers, the spread of crops and cuisines. They might follow how potatoes and chillies arrived with Portuguese traders, how rice cultivation spread along river deltas, or how spice routes rewired global economies and tastes.

An urban planner in Bengaluru might overlay colonial lake maps with today’s stormwater drains to see why some neighbourhoods flood every monsoon. A tourist might see vanished markets and fortifications appear on their phone during their walking tours, and receive information about ancient delicacies (and maybe directions to places still serving them). Communities could add their own migration stories and local legends, creating a more complete record of how cities were actually lived in—not just ruled.

New project! We mapped Bangalore's natural drains to show how water flows and collects, and some identified locations which flood often. Find your area, or just pan around to see how water ends up in the nearest lakes and reservoirs. w/ @Vonterinon

— Aman Bhargava (@thedivtagguy) November 19, 2024

https://t.co/W9sYZxbHS7 pic.twitter.com/NgpUyzGS5P

Through augmented and virtual reality, these maps might bring ruins and lost worlds back to life. A child standing in Hampi might see the city as it once stood: grand temples, bustling bazaars, busy forges, and colourful festivals. Modern highways could dissolve into the ancient roads where Chandragupta Maurya’s armies once marched, giving us a layered sense of continuity.

These maps might also acknowledge that history itself is contested space. Layers could present alternative versions of events and borders, letting people explore how interpretations differ across time and cultures. Rather than fixing a single narrative, maps might become tools for recognizing complexity in our narratives, and realizing that history is not a universally shared story of the past.

For decision-makers, maps layered with cultural memory offer value beyond archival curiosity. Conventional data layers can pinpoint where congestion builds or growth accelerates, but they don’t explain the patterns. These maps might. They would reveal wetlands buried under housing—explaining why certain neighbourhoods flood despite modern drainage—migration routes that evolved into trade corridors, and cultural anchors like shrines, markets, or old roads that still influence how communities move and gather.

This deeper context changes outcomes. A highway or tech corridor designed only on present-day snapshots might appear efficient on paper yet slice through a long-standing community hub or rest on a drained lakebed, creating friction or future disaster. When maps reflect these layers, they also build trust. People are more likely to back projects when they see their histories and landmarks acknowledged, rather than erased.

By layering historical and cultural insight onto AI-driven models, leaders can move from reacting to today’s trends to anticipating tomorrow’s risks and opportunities. These maps turn planning from a narrow technical exercise into a more complete understanding of how places and people evolve. They help decisions endure.

The maps of tomorrow will chart every highway and hum with intelligence, but they’ll also need to hold space for our past. They must remember the temple and the shop with blue shutters—the human layers we once navigated by. The best maps will always hold two truths: the monuments we build, and the stories we can’t bear to lose.