[When attention, not authority, becomes the centre of the classroom.]

Late one evening, in an extravagant mood, I signed up for the Harvard Bok Higher Education Teaching Certificate Program and paid the fee before I could change my mind. Years of teaching had given me confidence in my subject, but they had also, almost imperceptibly, dulled my curiosity about how students were actually learning. Predictably, doubts followed. Why commit to an eight-week programme now that I had already “hung my sandals”? What could I possibly learn at this stage of my academic life?

Yet I have always believed that it is never too late to learn. More importantly, I was increasingly curious about what it means to be an effective teacher today—when authority, information, and attention have shifted, and experience alone no longer feels sufficient.

Eight weeks later, I found myself changed in ways I did not expect.

The course did not offer quick techniques or fashionable prescriptions. Instead, it quietly but insistently forced me to re-examine who I thought I was as a teacher, and what I believed actually helps students learn. It challenged long-held assumptions about rigour, authority, and design, and replaced them with something more demanding: intentionality.

This essay is a reckoning of sorts—of shifts in mindset, methods, and approach that have reshaped how I now think about teaching.

I came to academia later than most, and by conventional measures was seen as an effective teacher. And yet, the Harvard Bok program forced an uncomfortable clarity: I realised I may have been reaching only the most engaged quarter of the classroom, not the class as a whole.

One of the first assumptions the program unsettled was my understanding of rigour. At Bok, rigour did not come from covering everything. It came from slowing down, choosing a few foundational ideas, and returning to them until understanding deepened. By contrast, much of our academic culture in India equates rigour with range—with cramming every possible topic into a course. The unintended consequence is cognitive overload: students under pressure, resorting to memorisation rather than building the habits of critical thinking that rigour is meant to cultivate.

In hindsight, these were not separate problems at all, but symptoms of the same drift—from teaching as engagement to teaching as delivery.

The program also made me confront something more mundane—and more uncomfortable. Over time, the PowerPoint slide had quietly taken centre stage in the classroom. Glued to the screen, it became easy to teach through the deck rather than to the students. Eye contact thinned. Rapport weakened. Sensitivity to who was following—and who was lost—diminished. What was gained in structure was often lost in presence.

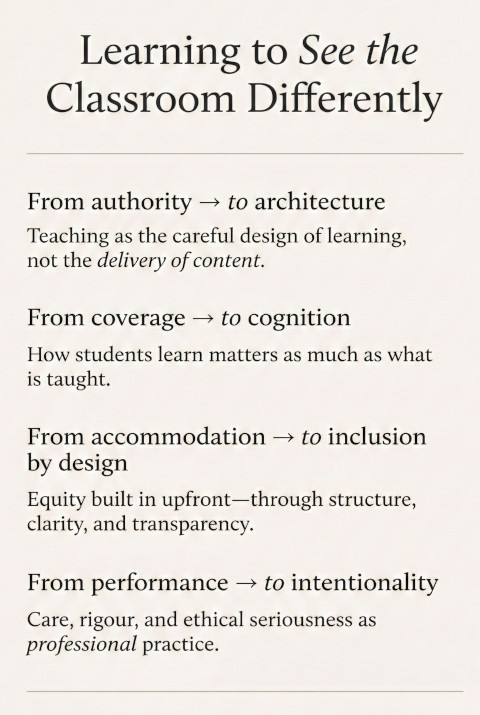

What followed was not a set of new techniques, but a more fundamental shift in how I understood my role in the classroom.

From Authority to Architect

The most significant shift occurred while writing my personal philosophy of education in the final module. Until then, my beliefs about teaching existed as fragments—intuition shaped by years in the classroom, refined through practice, but never articulated as a coherent stance. Putting those beliefs into words forced a reckoning. It required me to examine not just what I did instinctively, but why I did it—and to recognise how rarely I had paused to examine the assumptions beneath my practice.

Writing that philosophy was both empowering and unsettling. It made me recognise the agency I have always had as a teacher, even within institutional constraints—and the responsibility that comes with it. The question that stayed with me was an uncomfortable one: had I used that agency deliberately enough to transform learning within my reach, or had I too often relied on habit, goodwill, and experience to do the work for me?

At the same time, a long-standing assumption ruptured. For much of my career, I had understood authority in the classroom to flow from mastery over content—knowing more, knowing it better, and being able to explain it clearly. That assumption had served me well for years. But in a world where information is abundant and easily accessible, it began to feel insufficient. Authority, I realised, can no longer rest on knowing more. It must come from helping students think better.

I began to see the teacher less as a fountain of knowledge and more as an architect of learning. An architect attends carefully to foundations, designs structures that can bear weight, and builds layer by layer with intention and precision. In teaching, this meant shifting my attention from what I wanted to cover to what students needed in order to build understanding over time—what had to be made explicit, what could be scaffolded, and where support was essential. Teaching, I realised, demands the same discipline: designing learning so that understanding is embedded in every micro-process, not left to chance.

Until then, preparation had meant mastering content and anticipating questions. This time, planning felt unfamiliar. I found myself lingering over different questions: where might students stumble without even realising it? What assumptions was I making simply because they felt obvious to me? What was I leaving unsaid because years of familiarity had rendered it invisible? Preparing to teach now felt less like organising material and more like uncovering blind spots. Design, I realised, required a different kind of attention—slower, more deliberate, and far less comfortable.

This shift changed how I viewed even familiar practices. In one group discussion, we explored how a course might be contextualised before content is introduced—what counts as knowledge in a discipline, how it is created, who creates it, and how it is used. As the conversation unfolded, I realised how rarely I had paused to make these assumptions visible to students. I began to see that such framing is not neutral. It quietly shapes how students later distinguish between thinkers and practitioners, and, more subtly, the kinds of futures they allow themselves to imagine—and which ones they rule out early.

Another discussion focused on how students read and annotate academic texts. As we shared our annotations, I was struck by how differently students had engaged with the very same article. Passages I skimmed had been carefully underlined; ideas I assumed were obvious had been missed entirely. It was a quiet but unsettling reminder that cognition is not uniform. In that moment, I realised how often I had been designing courses from the centre of my own expertise, rather than from the varied vantage points of my students.

Designing for How Learning Actually Happens

One of the course’s most sobering reminders was that students do not learn the way teachers do. This seems obvious when stated plainly, yet it is easy to forget in practice. Experience, I realised, can quietly blind us to how steep the learning curve remains for novices, and to how quickly cognitive overload can set in.

Paying closer attention to how learning actually happens—how memory works, how attention falters, how meaning is constructed—became unavoidable. These processes are not discipline-specific. Whether one is teaching sociology, mathematics, management, or computer science, the basic architecture of learning matters, and it places limits on what students can absorb, no matter how well intentioned the teaching.

An assignment that brought this home involved designing learning materials for a single mother juggling study with childcare and work. As I worked through the brief, I became acutely aware of how narrow my default assumptions had been—about time, attention, and uninterrupted focus. Her challenges—fragmented time, competing demands, cognitive overload—were not incidental; they were structural. Confronting them forced me to reckon with how easily “rigour” becomes a shorthand for uniform expectations.

That reassessment stayed with me. In a more personal way, I found myself returning to a simple image: a student trying to follow a recorded lecture late at night, pausing frequently as a young child called out from the next room. It made visible how casually we design courses around uninterrupted attention, and how exclusionary that assumption can be. Rigour, I realised, cannot depend on ideal circumstances that many students simply do not have.

From there, my attention began to shift—slowly and somewhat uneasily—to design choices I had long treated as secondary. Prompts, sequencing, and reinforcement—elements I once dismissed as technical or logistical—started to feel consequential in ways I had not fully appreciated before. I found myself lingering over small decisions: what was made explicit, what was left implicit, what kinds of support were assumed rather than deliberately designed for. Over time, a simple but unsettling realisation took hold. Design is never an afterthought. It is where equity and effectiveness are either quietly built in—or quietly lost.

Another idea that reshaped my practice was backward design. Instead of organising courses around textbook chapters or inherited syllabi, the process begins with a simple but demanding question: where should students be by the end of the course? Evidence of learning, evaluation criteria, and classroom activities are then aligned deliberately to that end.

I tested this approach on an existing syllabus taught by a colleague—resisting the temptation to add or subtract content. The exercise was deliberately modest: to work only with what was already there. As I began to resequence the material around clear learning goals, relationships between concepts became more visible. Ideas that once felt dense became more legible; discussions gained momentum because students could see where they were headed. The effect was quietly revelatory. Teaching, I learned, is indeed a means to an end—not an end in itself.

Active learning techniques reinforced this insight, but not in the way I expected. I had used many of them over the years—group discussions, concept maps, short exercises—often with the sense that I was doing the right thing. Yet, revisiting them through the lens of design, I could see how easily they slip into pedagogic flourish, adopted more out of habit than intention. What changed was not the activities themselves, but how deliberately they were planned and positioned within the learning journey. When used with care, activities such as concept mapping do more than enliven a class; they help students synthesise ideas, see relationships, and move from recall and understanding to synthesis and creation. The difference, I realised, lies not in novelty, but in intention.

Teaching as a Caring Relationship

One of the course’s quietly radical propositions was this: inclusive teaching is good teaching.

Inclusion was presented not as accommodation or charity, but as design. A case study involving a mid-career student returning to education after two decades forced me to confront how easily academic norms assume continuity—recent schooling, familiarity with classroom conventions, ease with academic language, comfort with speaking up from the very first class. None of these were deficits; they were mismatches. What struck me was how quickly such assumptions become invisible to teachers, and how costly that invisibility can be for students. I began to see how equity could be built into courses upfront—through structure, clarity of expectations, and transparency—rather than addressed later through ad hoc exceptions.

This reframed my understanding of inclusion. I began to see that it was not about slogans or special cases, nor about responding to difference after it appears, but about recognising power, privilege, and difference as central to the learning environment from the outset. When inclusion is approached this way—as a matter of design rather than accommodation—it does more than widen access. It improves learning for everyone.

Equally transformative was the emphasis on teaching as a relationship. Building rapport, I learned, is not “softness” or personality-driven performance; it is foundational to learning. Trust enables attention, motivation, and persistence—but it is rarely instantaneous. It is built, quietly and unevenly, over time.

In one exercise, I recorded short teaching simulations focused on rapport-building—using students’ names, sharing parts of my own journey, and showing interest without intrusion. Watching those recordings back, I became aware of how deliberate such relational work needs to be to remain professional rather than performative. When done well, it becomes a form of capital. As one academic put it, rapport is like saving money: earned gradually, stored carefully, and drawn upon when needed—for motivation, classroom management, or moments of difficulty.

This relational lens also sharpened my awareness of expert blindness—the gap between what teachers assume and what students actually know. I recalled a student describing her first finance class, overwhelmed by unexplained jargon and ready to opt out within days.

She told me she spent the rest of that first lecture frantically copying down unfamiliar terms, afraid to ask questions and already wondering if she belonged in the course at all. The concepts themselves became clearer weeks later, but her confidence took much longer to recover. What the teacher likely read as attentiveness was, in fact, silent struggle. That gap—between what the teacher assumes and what the student experiences—can quietly determine who stays and who slips away.

Meeting students where they are, slowing down when needed, and using analogies to bridge gaps are not signs of dilution. They are acts of respect. They acknowledge the asymmetry of power and knowledge in the classroom—and the responsibility that comes with it. To teach well, I began to realise, is not simply to transmit understanding, but to remain mindful of where authority lies, and how carefully it must be exercised.

Feedback, too, took on new meaning. I had long seen it as administrative—for appraisals, grades, and evaluations. The course reframed it as developmental. Formative feedback, offered early and specifically, allows students to act, revise, and improve while there is still time to do so. It keeps the teacher engaged in the learning journey, not merely its assessment. In that sense, feedback is not a judgement delivered at the end, but a form of accompaniment—one that asks the teacher to stay present, attentive, and accountable.

In this sense, feedback changes teachers as much as students. It cultivates reflective practice.

What I Will Teach Differently Now

Redesigning even a single class forced me to confront habits I had normalised and assumptions I had stopped questioning over years of teaching. Practices that once felt settled—yet earned—had quietly hardened into default settings. Sitting with that realisation was uncomfortable. It asked me to acknowledge how easily experience can turn into routine, and how rarely we pause to examine what routine obscures.

Learning again, at this stage of my career, was therefore not an act of renewal so much as a reckoning. It felt like a liberating purge: unsettling, corrective, and long overdue.

Teaching, I now see, is not charisma or performance. It is a discipline—one that demands design, care, and ethical seriousness. What sustains it is not authority alone, but intentionality, exercised thoughtfully and over time.

My sandals are back on the rack.

But my commitment to learning, reflecting, redesigning—and being reviewed—continues.