[Clockwise from top left: A miniature umbrella-making workshop, where the master craftsman guided us; Kiyomizu Temple, Kyoto; Arashiyama bamboo forest; a wagasa umbrella]

My first impression, as I arrived in Japan, was a negative one. I had landed at 8 am Tokyo time into Narita airport, and as I queued up for immigration there were barely two counters that were manned. Both were working at a glacial pace taking minutes to process passports that should have taken seconds. I reflected then on the pleasant experience I had on my way out at the Mumbai airport immigration counters. Numerous manned counters, barely any lines and a breeze through. Did I need to fill an immigration form, I had asked the attendant manning the queue. He had given me a quizzical look as if to suggest: had I arrived recently from a mofussil town?

And here I was in Tokyo of all places waiting for close to an hour to get processed. Eventually, after a wait of almost 45 minutes, more immigration officers started arriving, the line split up, my passport was processed and I was sent on my way in.

That, as it happens, was the only negative experience of my eight days stay in Japan.

Japan was on my bucket list for long, and I was thrilled to be there. I studied Toyota in college, worked for Sony, fell in love with Japanese food, but never really had the opportunity to go to Japan. Now that I was there, I didn’t realise how deeply I would be affected by the country’s culture and its social contracts.

I was visiting with a group of my students of the Family Managed Business program at S P Jain Institute of Management and Research at Mumbai, where I teach retail. A foreign visit to study retail was a part of the course work. Previous batches had visited mostly European countries. I felt that European retail is too process oriented and structured along the lines of American retailers, a framework that the entire management education system in India is largely based on. Being an Asian country, Japan would be an interesting counterpoint. They had a few retailers that were established internationally, 7Eleven, Uniqlo and Takashimaya amongst them. But they also had a large number of traditional multi-generational family managed businesses that were quite unique, and their management had evolved in interesting ways. It would be interesting for my students to meet with them and study their methods.

Did I have a personal motive? Perhaps. I have been an admirer from afar of Japanese products, I drive a Japanese car and cannot think of switching to another brand, and Japanese is my go to cuisine, and I had long been drooling, thinking of trying out the authentic stuff. Good thing then that as I sold the idea to my students, they quickly bought in. So here we were for a 6 days trip to Tokyo and Kyoto, meeting with owners of small and large family owned businesses, along with a few cultural experiences thrown in. And I planned to stay back for a couple of days in Kyoto, to soak in the country a bit more.

Back at Narita airport, as I stepped out to grab my bag, I was awestruck by what I saw. Each bag on the carousel was neatly stacked on its side as if in a bookcase, with its handle facing outwards, making it effortless to lift the bag off the tray, however heavy the bag may be. I had never seen anything like this anywhere. In most cases, bags drop onto the carousels from the inner belt landing any which way, as passengers scramble to retrieve them. Was I imagining that the sideways stacking seemed to make the waiting passengers more disciplined? There was surely a lot less pushing around to retrieve the bags. I had to go and check how this was done. As the bags dropped off from the inner belt on to the carousel, a uniformed attendant was waiting and turning the bags on to their sides. Simple really!

[The Luggage Belt at Narita. Photo credit: loperthehoper/reddit]

Most airports around the world have attendants around baggage carousels, many have implemented complicated technology for baggage management. Very few however, have thought of such simple solutions to deliver efficiency and customer convenience.

Japanese efficiency has been much written about and discussed. Even then, it hit me like a flood. But as I saw more examples of it, I began to feel that for the Japanese, efficiency is not an end by itself. It is an outcome of a cultural ethos that is as considerate towards others and the world at large, as the rest of the world is at tearing itself apart.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

Before I left, a friend who is the CEO of the India business of 7Eleven, told me about what a stickler for time the Japanese are. They start to panic if the other person is minutes late, moreover it is viewed as disrespectful to be late for meetings. And the traffic excuse does not work. Everything runs on time. This I knew was going to be my biggest challenge. I was shepherding early twenty-somethings who were in a group and were used to partying late, especially when they were in an exotic country that they were visiting for the first time. Needless to say, my team and I had a hard time of it. It did not help that our Japanese contact inevitably arrived at the hotel an hour before the scheduled departure, and the bus was at the hotel parking lot at least 20 minutes prior to departure. Much cajoling, WhatsApp group messaging and threats of disciplining later, we all settled into a somewhat uneasy truce, and managed to reach most meetings without putting off the hosts. On the other side, the hosts were inevitably ready and waiting when we arrived. I realised that this is more than just a norm, it is part of a social contract, a mark of respect for the other person that is endemic to that culture. It is only fair then that a reciprocation is expected.

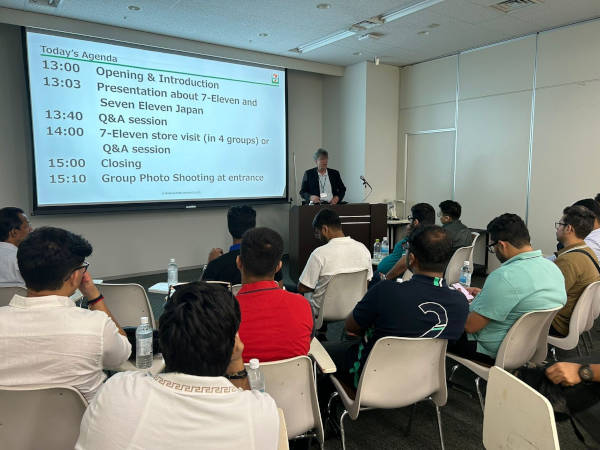

But it does not end there. At a visit with 7Eleven Japan, one of their senior most leaders made a presentation to us, starting bang on schedule. The first slide laid out the agenda, two presentations, followed by a Q&A session, followed by store visits. Each item had a time slot against it. As the two presentations followed, I was looking for signs that I inevitably feel when I make a presentation to a time slot. Am I overshooting? Did I spend too much time on the last slide, do I hurry through the next one to stick to the time limit? Maybe it’s ok to overshoot by a few minutes? I saw none of that here. The first presentation switched over to the second one right on cue, and seamlessly without any sense that the speaker was in a hurry to wrap up, as did the next one. This can work either of two ways. One, it requires terrific practice. Two, it is so much a part of their culture that it flows naturally to the presenter.

[Sticking to schedule at 7Eleven Japan]

Japan has one of the most complex train networks in any country. Not just the cross country Shinkansens. Each major city has a complex metro network. Even a relatively small city like Kyoto (population 1.5 million) has a network that seemed to me more extensive than Delhi metro, India’s largest with a population that is 20 times larger. I used this network extensively in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka at all times of the day, including during peak hours. And I could set my watch by its timeliness. Inevitably. Every time. Hell, even the buses run on schedule!

Timeliness is one expression of a culture that is endemic to Japanese society. It is never an end in itself. It is an expression of respect, if I value your time, I value you. And timeliness is only one aspect of this sense of respect.

In the extensive metro train networks across Japanese cities, no one pushes or is impatient to get off or on to the trains even at peak hours. Everyone is waiting to board in neat lines, waiting calmly as the doors open and the passengers deboard, just as calmly. With a lifetime habit of jumping on and off Mumbai suburban trains (and now pushing on and off metros) this was a bit of a shock to me and I found myself getting fidgety with my ingrained habits. Once on the train, no one is speaking on their phones, this is considered to be disrespectful, and getting into the spaces of people standing or sitting close to you. People are on their messaging apps, but rarely did I see loud conversations on the phones, not just on trains but also in public spaces.

This sense of respect extends to kindness in some unexpectedly surprising ways. On one occasion, as I was scrambling to pull out some change from my overcrowded pocket at a metro station to buy a ticket, the coins spilled through my fingers and clattered onto the floor. As I kneeled to pick them up, a stranger, perhaps in her sixties, joined me on her knees, helping me to gather the coins. As I awkwardly thanked her, she responded with humility, as if this wasn’t really an uncommon thing.

This respectfulness as a part of a national value system moved me deeply, coming as I was from an environment that is deeply divided, and shrilly demanding of personal rights to the total exclusion of a sense of corresponding responsibility. I was on the lookout for signs of fraying—were people feeling pressured to conform? At least some youngsters waiting to jump the queue and break a few rules? I didn’t see any. I admit that eight days is too short a visit to notice some of these, and perhaps some of these rebelliousness would become visible if I stayed longer. But when a value is deeply entrenched in a society, that brings in a sense of flow, a naturalness, that was clearly visible to me.

Technology is everywhere, but with a human touch. All tickets are machined, with slots for cash, coins or cards. All machines work in English, you punch in the destination station on a touchscreen keypad and it will show the ticket denomination. Really intuitive to use. And most stations have a manual counter as well if you so wish, and they speak in workable English. On one occasion I somehow meandered from one metro line to another for a multi-line journey without having to cross the intervening gates where they process the ticket. As I boarded the next train I realised that I had bought a ticket only for the first leg of the journey and was now travelling ticketless. I panicked a bit, but then intuitively sensed that it was going to be fine. As I reached my destination, I walked to the gate counter and told the officer what happened and that I had boarded from such and such station. He didn’t question the truth of my story or even raise a doubt that I may have been travelling in from further away. No fine was charged either. I just paid the ticket amount from the boarding station and walked out. If a society is basically honest, trust is also inherent.

If respect and trust is endemic to a society, it can only emerge from a strong sense of self- worth. This became quickly evident as we met leaders of businesses and understood their approach.

We met several family managed retailers, some small, some very large. Amongst the small ones were a kitchen knife maker, and an umbrella and lantern maker, both traditional crafts of Japan, both businesses were multi-generational. Kamata was a maker and retailer of exquisite kitchen knives in Tokyo. Kitchen knife makers have a reputation for high quality, and have an interesting history. They were originally sword makers for samurais. As the samurai culture waned in the mid-1860s, these sword makers evolved to crafting knives. And knife work is very important in Japanese cuisine, including, but not limited to making the best sushi.

The present owner was Seiichi Kamata, whose grandfather started the business in 1923, his son has now joined the business. In spite of his age—he is now 80—and the fact that he runs a large business which in rupee terms has a revenue of around 500 crore, he still made the best knives by hand himself. The knives were pieces of art, as much visually alluring as they were superbly functional. But the key to Kamata’s success was not just the product, but also the ability to personalise the service. As the salesperson packed the knife I bought, he asked me if I would like my name engraved on the knife. Of course I said yes, and Kamata-san personally hand-crafted my name on the blade!

[Kamata-San engraving my name on my knife]

[Outside the Kamata Store]

The other visit that was truly memorable was with Hiyoshiya, a maker of traditional handcrafted Japanese umbrellas and lanterns, made primarily of bamboo and paper. As a guest you can participate in an umbrella making workshop where they teach you to make miniature umbrellas. My students and I participated in this workshop, and then the owner took us through his store and showed us the various works-in-progress.

The umbrella making workshop was an amazing experience. The master craftsman taking us through the workshop did not just show us how to make the umbrellas and leave us to our devices. He came to each of us and helped perfect the shapes and folds. The last bit, a precisely folded paper cap atop the umbrella, tied in a perfect double stringed knot was well beyond any of us to get right. The gentleman personally did the fold and the knot for us. All twenty of us. Patiently and perfectly. Even the production output of a workshop of first timers, was a reflection of his craft, he could not let it be imperfect. On the other hand, from our point of view, think of the little joy each of us carried back, with a perfectly crafted umbrella that we largely made, even if we required a little help to finish.

[Miniature umbrella making at Hiyoshiya]

Later as we were taken through the store, we witnessed exquisite lanterns made of bamboo and washi paper that were works-in-process. They were called wagasa, a 1000 year old traditional craft which was dying out, before Hiyoshiya rediscovered and contemporised it. One particular piece stood out. Apparently, a similar piece was the centre-piece of the lobby at Ritz Carlton Kyoto. A guest was so impressed by the piece that he wanted to buy one for his home. Price: a cool Rs 60 lakh.

[The expensive Wagasa Lantern]

A few things stood out from these visits. First, they had a great sense of pride in their work. When a new generation entered the business, they ensured that they spent years mastering the craft before getting involved in the business aspects. They were master craftsmen first before becoming businessmen. This allowed them to completely own the process and innovate where required from a space of knowing. Two, they were disinterested in top line growth for the sake of growth. But their craft was so value-added that customers across the world (and all of them had customers around the world) were willing to pay a significant premium for that value addition. They saw themselves as artists and their artistry allowed them to charge a premium well in excess of what they would have been able to charge if they saw themselves merely as businessmen or even craftsmen. The Kamata knives were visually exquisite as they were functionally outstanding. Hiyoshiya had reconfigured the 1000-year-old art of wagasa lanterns and had contemporised it; they were simple and exquisite. Both had small stores with attached workshops, both had revenues in excess of 500 crore in rupee terms. So if one applies conventional sales per square feet metric the number would be mind boggling. But the point is that to understand these businesses we have to shift our own framework; conventional frameworks will not work. And their pride in their work is humbling to see.

The best large retailers also largely underscore the same set of values. We saw this with a large jewellery retailer and a multi-product cosmetics retailer. They don’t overtly drive the topline, they are focussed on owning product creation or designing the process to make it consistently innovative and value added. They are not in a hurry, they don’t have a valuation goal to meet, so the growth is natural, organic.

7Eleven has 28,000 stores in Japan. Many stores are across the road from each other, yet its innovation levels are such that not only do these stores survive, they thrive. Food to go is their primary product line and in order to maintain newness, they introduce a hundred combinations of food every week and replace 70% of their assortment yearly. Thus they can well maintain enough of a variation in assortment in stores even across the street to maintain their newness.

Given this complex network of stores, conventional wisdom would suggest that 7Eleven restock the stores by a method known as auto-replenishment, where the retailer simply looks at data of what is selling and auto-creates an order to send the goods that have sold out back into the respective stores. Hence auto-replenishment, simple and effective. But not for 7Eleven. Almost all the stores are run by franchisees, who operate as independent business owners. 7Eleven understands that giving control to the franchisee is the key to success. So while it provides all the sales and merchandise data to the franchisee, it expects the franchisee to take the initiative to place orders. It ships orders to stores two-three times daily in order to maintain freshness, and has a process to discount unsold food items where the discount is shared between the franchisee and 7Eleven. A true sense of partnership underlines the relationship, 7Eleven’s willingness to give control of the front end of the business to its franchisee is quite unique, to my understanding, in franchised retailing. It is perhaps even unique to Japan, 7Eleven follows a country specific master franchisee model in its international business, where the decision on whether to sub-franchise or to operate stores on their own is left largely to the master franchisee.

[With the 7Eleven Team]

Again and again we would ask questions regarding marketing strategy or customer profiles, and would find the answers inadequate or uninformed. Then we realised that if you make insanely great products, then that acquires its own customers, again and again, and the products sort of sell themselves, at a premium. Different lens, different framework. This idea takes a bit of getting used to. Indian family managed businesses approach their businesses with a trading mindset. Since they primarily buy and sell, they do not have control over their source of production, therefore the concept of innovation and value addition is contrary to their approach. This was a crucial counterpoint for my students. We discussed this at length, as the key learning outcomes of our meetings. They agreed that this was truly something to absorb.

Given how uniform the concept of value addition and innovation is, I saw this as an expression of self-worth. It expresses itself quietly, unlike most countries across the world where self-inadequacy is translating into a constant shrill announcement of personal achievement, enabled through a pliant social media.

The combination of consideration for others and a deep sense of self translates into a liquid humility that is awe inspiring to see, simply because I haven’t experienced this as a uniform feature of a culture anywhere else, and acts as a counterpoint to what is happening in the rest of the world. The Japanese seem to be deeply aware and respectful of their place in the universe. The efficiency that is so noticeable everywhere in the country is perhaps an outcome of this awareness. Else it would be too difficult to hold on to it so uniformly and deliver it so consistently.

This sense of awareness is perhaps most holistically captured in the Japanese tea ceremony, which I experienced with my students. On its face it seems highly ritualistic, but the ritual is deeply meaningful. The quiet deliberateness of the process of mixing the matcha tea with a bamboo brush brings the tea maker to a state of mindful awareness, yet some of the actions, the way the cup is held and turned for example, shows a deep sense of respect for the person to whom the tea is being served. Respect for self, consideration for others. Yin and yang.

[The Tea Ceremony in progress]

Are there frays along the edges of this culture? Perhaps. During breakfast at my Kyoto hotel, a next table was occupied by a group of youngsters, perhaps late teens or early twenties, who were wilfully raucous, laughing loudly and making a lot of noise. They were unlikely to be drunk given the time of the morning, so they were clearly aware of what they were doing. I had no idea what they were saying or if they were being offensive in any way. But no one complained or said anything to them, everyone including the hotel staff pretended that things were normal.

Elsewhere, I came across a business executive in a suit, perhaps in his fifties, emerging from a taxi outside a metro station in Tokyo totteringly drunk. He struggled to pull out his mobile and then his glasses, and then peered at the screen closely which indicated that he was clearly unfocussed. On inquiring, I was told that drinking excessively under social pressure with office buddies has become a major cause for concern and such drunkenness was not uncommon.

One surprising aspect is what seems like an unequal place for women. We pressed this point with one of the business owners, what would happen if the next generation had a daughter instead of a son. Initially he sidestepped the question suggesting that it didn’t bear an answer since it is a hypothetical situation. Eventually he admitted that he would not be too keen to have a woman run the business. Once this hit home, I noticed that most businesses, certainly the family managed ones, were run by men; women tended to take on secondary roles.

The other thing I noticed was a strange disregard for an excessive use of plastic, especially for a country that is otherwise so self-aware. Dispensing machines are everywhere and they dispense everything edible, from drinks of all sorts, to chocolates and snacks to instant noodles. And everything is made of plastic. All foods and drinks available in convenience stores are packed in plastic. Plastic bags are used to pack pretty much anything you buy, except perhaps apparels in department stores. I did not ask if they have a recycling programme. Perhaps they do, but a significant amount of the plastic packaging seemed to be a single use variety.

And there is an eerie near total absence of trash bins in public spaces. I was told by my Japanese contact that their withdrawal was triggered by the Sarin gas attack in a Tokyo metro station in 1995 by a religious cult; the gas was hidden in a trash can. She softened this by adding that this has now become a norm, and people are expected to properly dispose of their trash at home which is then incinerated. Still it did seem to me to be highly inconvenient to not have trash cans at all in a country like Japan. The Japanese are equipped to carry their trash home for disposal, but for tourists it is a major inconvenience.

And yet it all comes together in a flow. The source of it is surprising though. For hundreds of years prior to the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s, Japan was a highly feudal society with a rigid hierarchy. Though the country was largely peaceful during the Edo period (early 17th century to about 1860s) it was entirely closed to outsiders, and people considered to be at the lower end of the social hierarchy faced severe discrimination. Some of this class system was dismantled after 1868, but perhaps the real trigger for change was the end of World War II when Japan had to rebuild its nation from scratch. So to have travelled such a long distance in a short period of about 80 years is something of a miracle.

No country has moved me in quite the way that Japan has. Its social maturity has a spiritual quality to it. In a time of deeply divided societies, entrenched positions and shrill nationalism, Japan seems to have gone through it all and emerged victorious through a period of post-war pain and rebuilding. Here is a view that the success of a society is measured not by the size and growth rate of its GDP, but in the maturity and peacefulness of its people. That should give us pause for hope, though the lesson might be that perhaps the way to emerge victorious is to go through a period of pain and messy fractiousness. And have faith in the light at the end of the tunnel.

I will be back for more.

Travel Facts

I didn’t find Japan quite as expensive as I had expected, perhaps because Yen has fallen against the dollar. Return airfares for direct flights were in the ballpark of Rs 40,000. It is possible to find centrally located 4-star hotels in Kyoto for Rs 5,000-7,500 a night. Tokyo is a bit more expensive, especially for downtown locations.

I had excellent meals for Rs 500 per person on average. This could be lower if you buy your food from 7Eleven or Lawson, and convenience store food is excellent on the whole. This will shoot up significantly if you visit the high-end restaurants. On the whole though, I didn’t find food too much more expensive than average restaurant food in India.

Travel is a bit expensive though. The lowest fare for the metro is Rs 100. Travelling by Shinkansen is expensive (our tickets from Tokyo to Kyoto was about Rs 12,000), taxis are exorbitant. All said though, travelling by metro within cities is easy, relatively cheap and the most convenient option. And there is a metro station close to pretty much anywhere you are likely to go.

Food Recommendations

Sushi. Assuming you don’t want to try Michelin starred options, the best bet is to head to Tsukiji market in Tokyo. It used to be the world’s largest fish market surrounded by restaurants. The main market has moved but the restaurants remain.

[Conveyor belt sushi]

I had excellent meals at Sushi Zanmai, which is a chain with many branches including Tsukiji, as well as at Tsukiji Kagura Sushi. The default here is Nigiri sushi, (rice topped with a slice of seafood). If you want maki rolls (wrapped in seaweed) you will have to ask. Remember that sushi here is unembellished with mayos and condiments, just rice, freshest seafood with a bit of Japanese light soy sauce and wasabi.

Noodles and Ramen. We discovered a hidden gem called Yumemiya at the corner of a narrow lane opposite Kyoto station. It’s a Teppanyaki restaurant run by a brother-sister duo (the sister is the chef, the brother looks after the front of the house). It’s a small 15 seater with four seats on the kitchen counter. I had Seafood Yakisoba noodles to die for and went back for more, even if I had to sit at the kitchen counter, elbow to elbow with other customers.

[The Seafood Yakisoba at Yumemiya]

I did try ramen, but I don’t eat beef or pork that most of the best broths are made from, so don’t go by my word on it. I had a veg version and found it bland.

Spiritual & Cultural Experiences

Tea Ceremony. We experienced the tea ceremony with Maikoya Tokyo. The experience was exhilarating as it was insightful. If twenty-somethings with short attention spans enjoy it, so will you.

[The essentials for the Tea Ceremony]

Kiyomizu Temple, Kyoto. Founded in 780, it is one of the oldest Japanese Buddhist temples in Japan, situated on a hill and built entirely of wood. Even if there isn’t a spiritual bone in your body, go for the architecture and the beauty.

[The Kiyomizu Temple in the background]

[Entrance to the Kiyomizu temple]

Fushimi Inari, Kyoto. This one is a Shinto shrine famous for its torii gates, each of which is dedicated to a departed soul and donated by the bereaved family. Located about a 20-minute train ride from Kyoto, it’s a couple hours walk to the top, especially because the initial bit is crowded with tourists. Take the trouble to keep going because the crowd thins and spreads out as you climb on and the experience of the peace and quiet makes it worth your while.

[The Torii Gates at the Fushimi Inari Temple]

Arashiyama Bamboo Forest. The bamboo forest is worth a visit by itself, but what I enjoyed even more is the Tenryuji Zen Temple built inside the forest area. Built in 1339, it is exquisite and very peaceful. It was a joy to just sit in for a while. What makes the experience even better is that it is surrounded by the most exquisite Japanese garden.

[At the Arashiyama Bamboo Forest]

[View From the Tenryuji Zen Temple, with a Japanese Garden outside]

Fu Fu No Yu Onsen. I had to try an onsen (hot spring) experience and I found this quite close to Arashiyama and clubbed it with my visit to the Bamboo forest. The water can get very hot though and the trick is to alternate between the hot and cold pools, I came out feeling thoroughly refreshed. Warning: no clothes allowed in the pool. And of course no photos either.

Nara. About an hour’s train ride from Kyoto, Nara is a picturesque town known for the deer that abound the town and have the right of way over traffic. They inevitably nuzzle you for food, but are mostly non-aggressive. Nara also has the exquisite Todaiji temple. The original building was constructed in 752 and reconstructed in 1692. It houses one of the largest bronze images of the Buddha, at 15 metres tall.

[Deer at Nara]

[The bronze images of the Buddha at Todaiji temple]

Capsule hotel. I almost missed out on this experience but found one located at the Osaka airport. I had about three hours to kill before the check-in for my flight opened, so I paid Rs 2,500 to spend that time inside one of the capsules. Although the space is compressed, it is comfortable enough for a short stay. It has top class shower facilities and food and drinks available off a dispensing machine.

[Capsule hotel]

Dig Deeper

Watch | 7Eleven is Reinventing its $17B Food Business To Be More Japanese | WSJ | Play Time: 7:22 mins

Read | A senior Indian executive in a Japanese bank reminisces about business culture | Outpost | Forbes India | Read time: 2 mins

Watch | The Reluctant Traveller Eugene Levy makes his way to Tokyo | Apple TV+ (needs subscription) | Play time: 38 mins

VIVEK PATWARDHAN on Oct 09, 2024 8:01 a.m. said

Superb story. Informative and insightful. Looking forward to more stories like this one about other countries. This story reminds me of an article I read (Marathi) where the author who married a Japanese girl and settled in Japan wrote about the differences and similarities of culture and traditions. I appreciate that the visit was a study tour, but no visit to Japan is complete without a visit to Hiroshima. It shakes one to the core. One abhors violence and understands the worth of peace and these feelings have lasting impact on our mind. Congratulations to the author of this article and to FoundingFuel, - Vivek S Patwardhan