(Photo from Pixabay)

It’s been a shaky start to 2025 for the Indian markets. After two years of soaring highs, the markets have finally hit a rough patch. Tariffs, geopolitical tensions, and a dose of uncertainty have sent stocks sliding into bearish territory. So far, the correction hasn’t been too deep, but every investor knows that when it comes to markets, there’s always room for more surprises.

Bear markets are never fun. Portfolios shrink, optimism disappears, and regret takes over. “Why didn’t I sell at the top?” is the question haunting many investors right now. But let’s be honest—could anyone really have predicted the peak?

As the market wobbles once again, the same questions arise: Should we sell our losing positions and move to cash? Should we buy stocks at lower prices? Or should we simply hold on and wait for the storm to pass?

Investing has always felt like a rollercoaster. Every twist and turn feels critical, every event seems like it could change the game. But if you zoom out, you realize that most of us will be investing for the long haul—decades, or even a lifetime. Along the way, there will be numerous bull markets and corrections.

If that’s the case, it’s surprising how little time we spend preparing for these inevitable ups and downs. Instead, we react with shock every time the markets turn, as if it’s the first time prices have fallen.

This is the idea explored in this investor guide on reconciling with market fluctuations. It attempts to provide a mental model for long-term investors to navigate market declines with greater clarity and calm. While the impact of falling prices cannot be avoided, it is indeed possible to prepare for and manage the inevitable fluctuations of the investment journey more effectively.

A Mental Model

The stock market alternates between peace and turbulence, with stocks biased to rise or fall. During a bull run, the market keeps making new highs before reaching a peak. Then, some adverse event happens, leading the market to fall and prices continue to decrease. After a while the decline stops and the trend reverses upward.

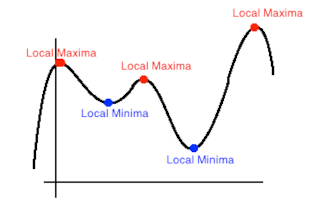

This pattern of alternating highs and lows reminds me of high school calculus and the concept of maxima and minima. The maxima is the maximum value at a given interval and the minima is the minimum value in that interval.

Look at the curve below. It has multiple maximas and minimas in each interval.

What is interesting is that a curve will have only one absolute maximum and minimum value, but it can have many maximas and minimas.

Returning to markets, as the stock price fluctuates, the resulting curve meanders and slopes, forming peaks and valleys—the maximas and minimas.

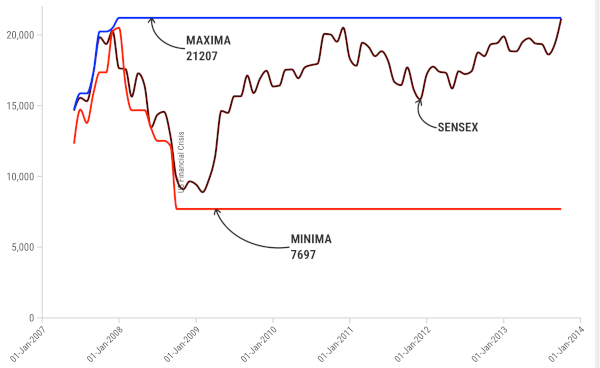

The figure below depicts the Great Financial Crisis.

(Sensex maxima, minima during the Great Financial Crisis)

Before the crisis, the Sensex had peaked in early 2008. The fall lasted 14 months. Looking back, we observe that the market fell from a maxima of 21000 and achieved a minima of 7000 (a 63% drop—the largest fall in the Indian markets).

Viewing stock prices as a series of episodes with their own high and low points is very useful. It becomes evident that a significant increase in stock prices (like the current markets) will be followed by a decline. At the same time, the current market high will be followed by an even higher peak in the future, but not before a trough in between.

However, in hindsight, we know that the market eventually went on to surpass even the pre-crisis peak.

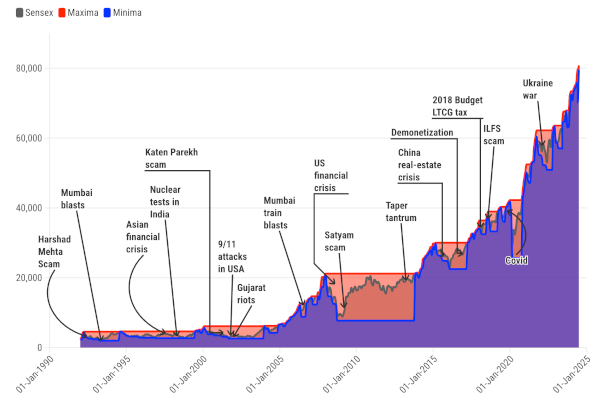

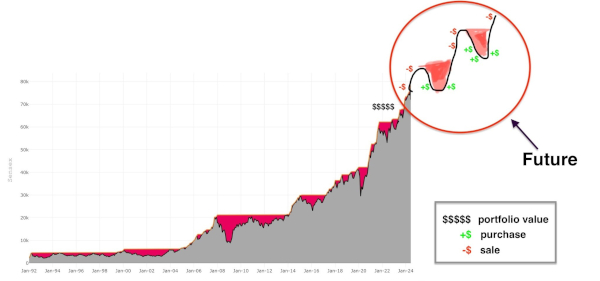

The below chart plots the Sensex over the past 30 years, including its maxima, minima, and the major crises.

(Thirty years of the Sensex, 1992-2024)

It is clear that the markets go up in the long term, but not constantly. The long-term upwards movement is the sum of many many episodes, each with its own local maxima and minima and accompanying drama.

In summary, as markets rise, they reach a peak, the local maxima, before prices fall. The market then meanders down to reach its lowest point, the local minima, before rising again to surpass the previous maxima.

The Psychological Impact on Investors

Ups and downs severely affect human psychology. The suspense of real-time price fluctuations weighs on investors. There is no way that they can know if markets are near the peak (in bull markets) or the bottom (in bear markets), since the maxima and minima can only be known in retrospect, not in real-time.

Let’s consider the markets’ fresh upwards move after a bear episode. Investors don’t know in real-time how far the market will rise, or if it’s a false start and prices will crash again. Affected by the previous downturn, many will naturally sell their holdings at the first sign of appreciation.

Even experienced investors can be baffled by the continuous price increases in a bull market (like the current one).

As the market keeps rising, every small fall presents a dilemma: is it a normal pullback, or the first step of a prolonged downturn? If there were a bell to announce the peak, everyone could sell and avoid significant corrections. But since the future is unknown, investors are forced to deal with the uncertainty and discomfort as they hold on to their stocks.

Being an investor isn’t easy. If you sell and the markets go up, it leads to resentment. If you hold and they crash, you regret not selling at higher prices.

The markets will eventually fall in response to an adverse event. As the decline happens, it’s again unclear where the lowest point lies. For investors holding stocks, the losses accumulate. 20-30% wealth erosion is normal. But these losses seem greater due to loss aversion bias (loss feels ~3x worse than a similar gain).

As investors endure price drops for months, their survival instinct activates, tempting many to sell and cut their losses. This holds true for even the most experienced investors, since the market’s potential decline remains uncertain.

Accepting the Inevitability of Market Fluctuations

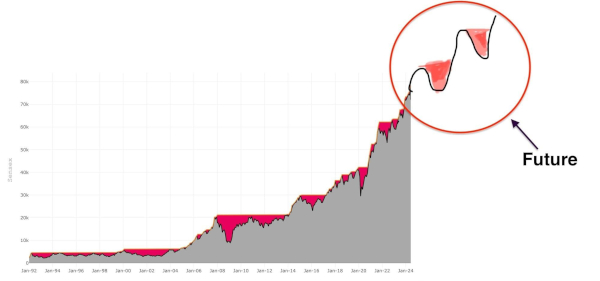

Viewing stock prices through the lens of maxima and minima has many advantages. Doing so, we explicitly acknowledge that the current drama is representative of the current interval. In the short and medium-term, the market will fluctuate, but the long-term trajectory will generally be upwards.

(The future market movement is very much known!)

Also, it is clear that one cannot jump to a future maxima bypassing the interim minimas. This mental model promotes the long-term mindset and discipline required to remain invested and grow wealth over time.

Drawdowns and Corrections

As markets rise, the investor’s portfolio keeps growing, peaking near the maxima.

A very interesting thing happens here. At the peak, the highest value reached by the portfolio becomes the baseline in the investor’s mind. Say, the investor started with Rs 20 lakh and their highest portfolio value stands at Rs 60 lakh. The investor’s mind is now anchored to this number. So much so, that if the portfolio were to drop to Rs 40 lakh, it feels like a real loss. The reality is that the investor is making returns of 100% (20 lakh –> 40 lakh), but that is not how our minds operate.

Even a paper loss feels significant. (This quirk of the human mind is called the anchoring bias).

As the market falls from its peak maxima, investors incur losses called drawdown losses, or simply drawdowns. The more the market falls from its maxima, the more severe the drawdown. Drawdowns reach their maximum at the point of minima.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the peak drawdown was 63%, meaning the average investor lost ~63% of their wealth compared to the previous maxima. The losses of the Harshad Mehta scam of 1992 and the Dotcom crash of 2001 were in their 50s, while the recent Covid crash was 40%. History shows that markets can fall, and fall significantly.

Selling in Anticipation of Market Decline

Why can’t smart investors sell at the peak of the bull market and avoid losses? This would save them much distress and, furthermore, they can buy back their holdings at the market’s bottom.

There’s a small problem. As the bull market proceeds, the investor can’t predict the peak maxima. The peak is only known in hindsight.

If an investor were to sell their holdings, and the market kept rising, it would invoke the worst kind of regret. It’s very tough to watch the stocks you sold keep rising. Most investors who end up in this position throw in the towel at some point and end up re-purchasing the same stocks at higher prices to alleviate their regret.

Ben Graham relates the story of Isaac Newton in The Intelligent Investor,

And back in the spring of 1720, Sir Issac Newton owned shares in the South Sea Company, the hottest stock in England. Sensing that the market was getting out of hand, Newton dumped his South Sea shares, pocketing a 100% profit of 7,000 [pounds].

But just months later, swept up in the wild enthusiasm of the market, Newton jumped back in at a much higher price and lost 20,000 [pounds] (or more than $3 million in today’s money).

Assume that there were men more resolute than Newton, who could sell all their holdings and resisted buying at higher prices. Eventually, the market will fall and stock prices will drop below our investor’s sale price. The problem now is: when does the investor buy? Since the bottom of the correction is unknown, there’s no point at which one can purchase without facing immediate losses.

Also, buying entire positions while the market news is bad and stocks are falling is extremely complicated.

The investor is caught like a deer in the headlights, with no idea what to do. In the process, he has permanently traded his long-term holdings. Bill Ackman nicely summed it up in a recent letter to his investors,

We do not typically sell our core portfolio holdings even if we believe it is highly probable that they will decline in price in the short term, as long as our view of their long-term potential remains largely unchanged.

A short-term trading program might enable us to avoid a small loss at the much larger cost of missing substantial stock price increases thereafter. As a result, we do not trade around our long-term holdings…

One may not always agree with Ackman's actions, but he is spot on here.

Living Through a Drawdown

When faced with drawdowns, the best course of action for an investor is to do nothing. The least that an investor must do is not sell their holdings during a correction, no matter how deep.

From a maxima and minima standpoint, a down period is simply the time before the next higher move that investors have to endure. (It is true that some stocks may never recover, but we’re discussing the market.)

In this light, drawdowns are a feature of markets, not a bug. Long-term investors are not expected to nullify these losses, but rather expected to take them on their chin.

Imagine that markets had no volatility, crashes, and drawdowns. Then all investors would readily invest in equities, as they invest in fixed deposits and bonds, without the fear of any loss. Evidently, the returns on equities would mirror those of safer instruments.

High returns do not come free. Investors seeking them have to bear some risk. Drawdown losses are the price paid by long-term investors for earning large returns. This is just how the process of risk works.

Charlie Munger had this to say to investors,

If you're not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century, you're not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you're going to get.

Market Bottoms Are Great Opportunities

As the market keeps falling, every piece of bad news is accounted for. Most investors who needed to sell have already done so. At this point, it takes only a small amount of positive news for a new upward trend to begin. Justin Mamis writes in The Nature of Risk,

The single best time to buy a stock—you can put this in your will for your grandchildren to rely on—is when given bad news, the stock refuses to go down any more.

Take the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, for example. The Sensex had a drawdown of over 60%. However, investors who bought at the bottom would have seen their investments appreciate by 100% to 175% as the market recovered and reached new heights. Bear markets offer long-term investors opportunities for significant gains at low risks. When fear peaks and the market absorbs negative sentiment, a powerful rebound is likely.

Stock market folks have a saying that “a stock that declines 50% must increase 100% to return to its original amount”. Conversely, buying at the bottoms, when a stock is already down 50%, is the safest way to make 100% returns.

One important point to note is that investors who are buying in a bear market don’t have to time the market’s absolute bottom. Purchases made at any level will make returns after the crisis is over and the market starts moving upwards. Obviously, buying when the pain is highest will be more profitable than buying very early. (If it is gut-wrenching, it is a signal to buy.)

However, buying during crises is easier said than done. With the investor’s psychology and survival instincts urging them to sell, it takes courage to step in and buy. One market guru commented that buying in crises “feels almost like death” while another said,

The very best stock purchases make you feel like throwing up.

Planning for Future Drawdowns

Drawdowns are the price of admission to equity markets. Trying to avoid these losses can lead to sub-optimal returns.

But is there really nothing that the smart investor can do to prepare themselves for the impending correction? Is it at least possible to soften the impact and ensure that we do not capitulate at the bottom of the market? And where does one get the cash to buy at the juicy valuations at the bottoms?

A Framework for Positioning for the Next Market Phase

Through our explorations into maxima, minima, and drawdowns, we have made some key observations:

1. Markets can keep rising, and no one knows their limits. The peak of the market cannot be known in advance.

2. Selling in bull markets feels foolish as stock prices continue to climb after the sale.

3. Corrections cause markets to plummet to extreme lows. The bottom of the market is unknown in advance.

4. Market declines are stressful and can easily lead to forced selling.

5. The easiest profits come from buying in the bleakest market conditions. But, it is very challenging to buy at market lows.

6. The markets will move from maxima to minima, and an even higher maxima.

Using these insights we deduce an action matrix for long-term individual investors.

In Bull Markets

Key Action: Sell

When: Avoid selling until optimism is high and memories of the previous bear market have faded.

What: Sell a small % of the portfolio. Selling some stocks entirely can create unhealthy psychology if they increase further.

How much: Sell a small portion (e.g. 5%) of the portfolio every 6-12 months.

Aftermath: After selling, the market will continue to rise.

Mindset: The market rise after selling will lead to regret, which is the desired psychological state.

In Bear Markets

Key Action: Buy

When: Strong corrections generally lead to 20-25% drawdowns. It’s wise to wait before buying, as cash is limited. A good rule is to buy only when it is gut-wrenching.

What: Buying in a crisis is difficult. One can only aim to buy more of what they already have or understand thoroughly.

How much: Consider purchasing in 2-3 installments. Timing the bottom isn’t essential

Aftermath: The market will continue to decline after buying, leading to losses.

Mindset: The immediate losses upon buying will lead to regret and introspection. However, this discomfort is an essential part of the investment process during bear markets.

In this framework, the investor is expected to act only in the late stages of both bull and bear markets. The recommended actions counter prevailing market behaviours and are designed to induce regret, positioning the investor as a (minor) contrarian, which is the goal.

Selling during bull markets can be emotionally taxing, but it’s a valuable strategy. As the market continues to rise post-selling, the investor will experience regret, leading to resentment towards further gains. This mental state prepares them for the next cycle. Some may even privately wish for a pullback to invest their cash at more favourable valuations!

Looking foolish at market extremes is necessary for making money in the longer term.

It's important to note that the amount of selling isn't as critical as the act itself. Even selling a small portion can generate the necessary regret and emotional conditioning to navigate the next market downturn. For instance, selling just 5% and retaining 90% may still cause significant regret as the market continues to rise.

I recently spoke to a prominent HNI investor who was regretting selling a multi-bagger stock (that he had held for years), because it had sharply appreciated after his sale. Later, I gathered that he had sold only 20% of his holdings and continues to hold the rest!

An investor who has already sold is both mentally and financially prepared to buy.

This forced-contrarian mindset allows long-term investors to anticipate sentiment shifts in advance. This is why successful investors hold more cash during bull markets, preparing for the next downturn. By embracing the emotional challenge of selling during bull markets, investors develop the mental strength to stay through the down cycle without capitulating, and also have some cash available to take advantage of juicy valuations.