[Image by Tumisu from Pixabay]

Good morning,

In his 2016 TED Talk, Adam Grant, author of Originals, shared some counterintuitive observations about creative people. They are not always first movers, for example. And they procrastinate, that is, they start early, and finish late. The time in between gives them original ideas. He quotes Aaron Sorkin: "You call it procrastinating. I call it thinking."

Grant shares two examples from history.

- Leonardo da Vinci toiled on and off for 16 years on the Mona Lisa. He felt like a failure. But some of the diversions he took in optics transformed the way that he modeled light and made him into a much better painter.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. was up past 3 am the night before the biggest speech of his life, rewriting it. He hadn’t finished even as he was waiting for his turn to go onstage. In fact, the four most famous words in the speech—“I have a dream”—was not even in his original script.

“By delaying the task of finalizing the speech until the very last minute, he left himself open to the widest range of possible ideas. And because the text wasn't set in stone, he had freedom to improvise. Procrastinating is a vice when it comes to productivity, but it can be a virtue for creativity,” Grant says.

In this issue

- What went wrong at The New York Times (and how to avoid a similar mistake)

- How to use a what question to figure out why

- How to spice up daily life with adventure and mystery

Have a great day!

What went wrong at The New York Times (and how to avoid a similar mistake)

In her powerful resignation letter to The New York Times, published on her personal website, Bari Weiss, who was a senior editor at the paper, shared what she felt was wrong with the newspaper. It failed to anticipate the victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential elections, in part because it was not listening.

In her resignation letter, Weiss wrote: “But the lessons that ought to have followed the election—lessons about the importance of understanding other Americans, the necessity of resisting tribalism, and the centrality of the free exchange of ideas to a democratic society—have not been learned. Instead, a new consensus has emerged in the press, but perhaps especially at this paper: that truth isn’t a process of collective discovery, but an orthodoxy already known to an enlightened few whose job is to inform everyone else.”

In an essay published by Founding Fuel in 2016, Arun Maira made a case for deep listening, as against debating. He submitted there were three levels of listening.

- The first level of listening is to pay attention to ‘what’ the other person is saying, even if one does not agree. The instinct of a debater is to get ready with a riposte to prove the other wrong. Therefore, a debater stops listening even while the other is speaking.

- At the second level, she wonders ‘why’ the other thinks the way he does. And, rather than debate the other, she asks the other, with genuine interest, ‘why do you believe what you do?’

- At the third level, the listener begins to notice the difference between her own way of seeing the world and the other’s. Thus she may begin to see her own lens.

Maira writes: “Our lenses are our ways of seeing and thinking. They are buried within the backs of our heads. We cannot see them with our own eyes. However, we may see them reflected in the eyes of another. Deep listening makes one aware of ‘who’ another is. Deep listening also brings self-awareness, of who I am.”

Dig deeper

How to use ‘why not’ questions to strengthen your ‘why’

In his famous TED Talk, which was viewed over 7 million times, Simon Sinek said great leaders inspire action by Starting With Why.

But, it’s no easy task. Writing in Harvard Business Review, Nancy Duarte, a leading communications specialist, says that most of her clients tend to focus on what and how, rather than on why.

Duarte offers three simple ways to get to why.

- Ask good what questions: For example, ask “what is at stake if we do or do not do this?” Or get someone to ask “so what” until you can’t answer it anymore. That will lead you to why.

- Fill in the blanks: “We need to <do X>, because _______ .”

- Articulate why you didn’t choose the alternatives: “By sharing the ideas that you considered, explored, tested, and then abandoned, you’ll demonstrate that you’ve thought through all the possibilities.”

Dig deeper

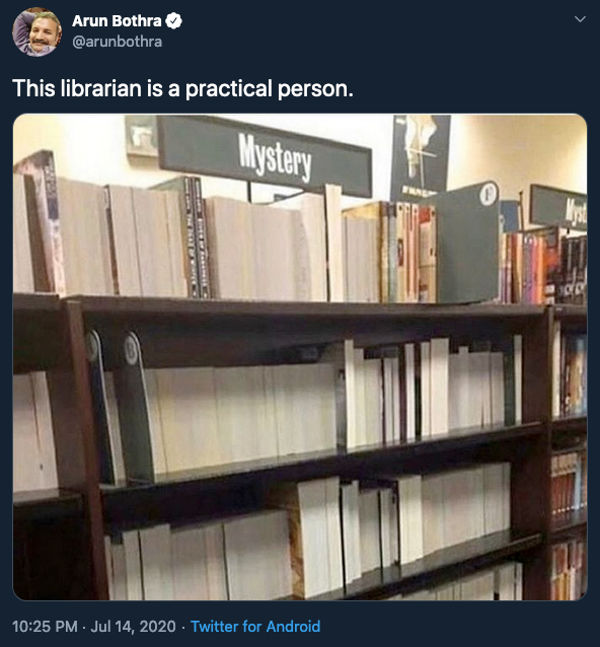

How to spice up daily life with adventure and mystery

(Via Twitter)

What are your favourite mystery books? Send us some hint, or share it on Twitter, tagging @foundingf. Or head to our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel