[Image from atherenergy.com]

Editor’s Note: Join our AMA with Hormazd Sorabjee, editor Autocar India, and Pranav Srivilasan on Saturday, October 12, 2024, 11 AM to 12 noon. Register here

Today, it might feel like an electric vehicle (EV) mania has gripped the world. Headlines about rising and falling sales, some brands declaring an electric future is imminent, social media grandstanding by electric vehicle enthusiasts and detractors alike.

The initial wave of early adopters—the environmentally conscious and tech enthusiasts—is being joined by a new cohort. Normal drivers who don’t think too hard about the technology or the environment but are intrigued enough by the promises of comfort, convenience and cost savings to dip their toe in.

In fact, EVs have already gone mainstream in the form of electric scooters. In the first eight months of this year, nearly one in five scooters sold has been electric.

Electric cars, however, have lagged well behind scooters, accounting for only about one in fifty cars sold today.

“I was one of the first five people to buy the Hyundai Kona. Then I lost it. My daughter took it and gave me a Honda City in return,” says B.V.R. Subbu, former president of Hyundai India, former board member at Ola Electric and former chairman of Ampere Vehicles. “Bad bargain for me,” he says with a chuckle.

While Subbu is far from an EV sceptic, he does voice a little caution.

“The noise about EVs is not all misplaced. Yes, there are lots of good things. I would give an unreserved yes for two-wheelers and three-wheelers. For four-wheelers in the commercial segment, yes,” he says. But for passenger cars? For primarily city use and some customer segments, yes, but it’s still a mixed bag for the mass market, in his opinion.

Still, the Indian car buyer today has more electric choices open to them than ever before, with on-road prices starting from about Rs 7.5 lakh for the diminutive MG Comet and ranging up to more than Rs 1 crore for luxury cars. And next year should see many more EVs come to market.

Hyundai is expected to roll out an electric version of its highly popular Creta SUV, while Maruti Suzuki is set to make its EV debut, also with a premium SUV. Mahindra has announced it will launch the first of its “Born Electric” range of cars, market leader Tata Motors is out to expand its lineup with bigger EVs, and MG Motor is in the process of launching multiple EVs.

At this point, you might ask, “Should I consider buying an electric then?”

To answer that, we explore the realities of the whole EV ownership experience, through stories from people on the ground. From ease of use to running costs to lawsuits over basement charging to safety and reliability.

Experience vs cost

Vehicles, at the end of the day, are an experience.

The one thing every EV owner I speak with returns to is just how different the experience is compared to a petrol or diesel machine. Smooth, quiet, relaxed and comfortable. The constant vibration that can be felt from your wrists to your chest while standing with the scooter engine running at a signal? Gone. The rumble and shake of a car starting up? Just a blink and a beep now.

Ashwin Sinha, a former startup founder and now an investor, pitched an EV when his retired parents needed a new vehicle. After a few discussions and trials, they were in, and he bought them the ZS EV from MG Motor at their Noida home.

“My parents were sold on smoothness, how little noise there is. Even on long rides—we go to Dehradun, Alwar, Jim Corbett—it’s very smooth and comfortable, without any shaking,” Ashwin says.

Yamini Madigeri and her husband Anoop decided to replace their old scooter a few months ago and decided to take a shot with an electric one from Ola. They have a car for longer drives, and the two-wheeler is for short runs in their South Bengaluru neighbourhood. “Nothing more than 2 km. Gym, badminton, sabzi, salon and timepass, basically,” Yamini says.

[Yamini Madigeri, a sales executive at a global research firm, with her Ola S1 scooter in JP Nagar, Bengaluru]

She doesn’t care much about the technical details and the specifications, but the difference between her old scooter and the electric one is night and day. It’s smooth and zippy, and some software features like maps are genuinely useful, she says. It also lets her do things she couldn’t before: “The road conditions are not great, so near this shop where I parked the road slopes down. Getting it out was a pain, you have to pull it out. Now, I have reverse mode.”

“Never going back to petrol,” she says.

The ease of driving and the comfort of an electric ride come at a higher upfront cost over petrol vehicles. But for buyers like Ashwin and Yamini, they can afford the premium and are more than happy to pay.

But does it make sense for you financially? That depends.

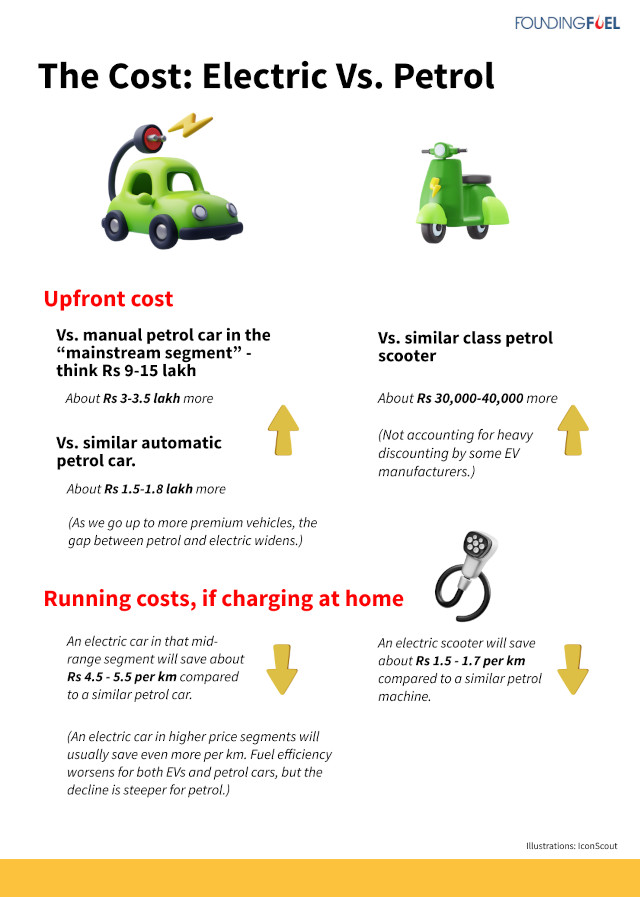

The relatively small price gap between electric and petrol scooters makes the former an easy choice, so long as one can manage cheap charging at home (we’ll come to that in the next section).

For cars, EVs feel significantly expensive compared to manual petrol cars, unless you run up a lot of kilometres on a regular basis and save a lot on fuel costs. However, the upfront price gap narrows when compared to an automatic car. And given that most EVs in India right now are still best as city cars, that might be a viable option for those of you who dislike the hassle of changing gears.

“An electric is the best automatic. It’s smoother and easier to drive than anything else,” says Hormazd Sorabjee, editor of Autocar India. With a handful of electric cars always waiting for reviews, from the diminutive MG Comet to the plush Hyundai IONIQ 5, he rarely finds himself driving a petrol or diesel vehicle these days. “For city use, if you can charge at home, an EV is almost a no-brainer decision.”

Charging and driving in the city

The big savings on fuel costs EVs tout, depends on being able to charge cheaply at home, using residential electricity rates. And there lies the challenge.

Unlike in markets such as North America or even much of Europe, many of us in Indian cities can’t easily wire up an electrical socket where we park our vehicles.

In some places, either there is no dedicated parking (true in much of Delhi proper), there is no economical or feasible way to wire a parking spot (sprawling gated societies with outdoor parking or high rises with multi-level lots), or the residents’ association doesn’t allow wiring out of (not unreasonable) fear and uncertainty.

Some buildings, usually smaller ones, freely allow installations as long as safety norms are followed. Some others allow network operators to set up points in common parking areas for all residents to use and pay for.

For Nikhil George, who lives in Mumbai and bought a Tata Tiago EV a year-and-a-half ago, setting up charging in his own parking space is not feasible. Like many in the city, he lives in a high-rise apartment. But his building has charging points set up by a couple of different private operators, placed in common areas.

“In my previous building, they had four common charging points and you could book slots through an app,” he says. With just a few EV owners, he used to find it easy to get a slot. In any case, he only needed to charge his car about once a week.

When he moved to a new complex this year, things got harder, even though it has five-six charging points. A couple—run by Tata Power—were out of operation for six months, and with many more EV owners in the new place and no slot booking system, he always has to keep an eye out for a free charger.

As a result, he often turns to public charging.

“Right next to my office, there’s a Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) parking lot with installed chargers. It was actually set up by Audi, so there’s Audi branding everywhere,” Nikhil says. That’s his alternative for weekly top-ups if he can’t do it at home, even though it costs more; public fast chargers cost about Rs 20-25 per unit, versus Rs 7-10 at home. Or if he’s going shopping or to a movie, he now prefers to go to a mall with charging points in the basement.

“I don’t regret buying the car. It’s been a great experience,” he says. “But charging infra is a problem.”

[Nikhil George, a finance professional, with his Tata Tiago EV in Wadala, Mumbai]

Yamini in Bengaluru, on the other hand, isn’t even interested in putting a plug point in her parking space, even though the building allows it. There are a handful of charging stations for two-wheelers and four-wheelers outside in the visitor parking. “It’s just so convenient. We pay something like Rs 60-65 for a full charge,” she says. “Maybe if we had an electric car, we might consider charging in our parking.”

But many housing societies across India’s metro cities have halted any addition of electrical outlets in parking areas. Occasionally, this sparks conflict.

Anand Vedula in Bengaluru has spent the past three to four years in a legal battle with his housing society. When he moved to Bengaluru in 2018 and bought a flat with a parking slot, he was allowed to put up a plug point for his Mahindra e2o. In late 2020 though, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, after an altercation with the president of the housing society on an unrelated issue, Anand found his line cut.

The association told him that his parking space was common property and he was not allowed to modify it. Anand went first to the discom and then to the municipal corporation, both of which said he was free to do as he saw fit (as long as electrical standards were met). In 2021, he went to court, and what followed was a series of court rulings in his favour, constant stonewalling by his opponent the president, allegations of bribery and more.

Anand looks set for a legal victory in the coming months. How has he been running his electric car the past few years though? “My brother bought a flat nearby, half a kilometre from my building. He doesn’t have a car so he let me charge in his parking,” he explains. “But I have to park it there, walk home and then walk back after a few hours when the charging is done.”

Not really a solution for everyone.

So, if you don’t live in an independent house where you can freely install whatever wiring you choose, before buying an EV, you may want to approach the housing society first. If they’re fine with it, and you can reach your parking spot from your electricity meter easily, then great. Which was what happened to me in Bengaluru when we bought our electric scooter, and three or four residents have followed suit in the years since.

But if there is opposition, it might be worth engaging in constructive dialogue.

“There are problems on both sides. Sometimes housing societies are against the idea and resistant to change. But some EV owners are also too high-handed,” says Raphae Halim. Quintessential early adopters, Raphae and his wife, Farah, have owned electric cars for 11 years now, having reviewed EVs and run the PluginIndia community for most of that time.

[Raphae and Farah Halim, EV reviewers and formerly part of the core team at PluginIndia, with their first electric car—a Mahindra e2o—in 2015 in Santa Cruz, Mumbai.]

The government, Raphae says, has made it clear that charging at home is a right. He emphasises though that electrical safety should be a priority. In his 28-apartment building in Santa Cruz, Mumbai, he’s the secretary of the housing society and encourages wiring up plug points in the basement. So long as proper earthing is in place, along with quality cabling of thick gauge, with cable trays to manage routing, he says one should have no concern.

When a manufacturer such as Tata Motors or MG Motor instals plugs at a customer’s home, they tend to follow electrical standards and safety norms to a tee. But the danger, Raphae warns, is if someone tries to hire an electrician on the cheap, who might cut corners.

Apart from that, he says, the only other consideration is the electrical load, which is something to manage with your discom. Your electricity bill will mention a “sanctioned load”, which is the maximum power you’re allowed to draw in one go. While a scooter charger will only draw as much power as a toaster or microwave, home chargers for cars can need as much power as two to four air conditioners.

In that case, you might need to fill out a form to get the discom to increase your sanctioned load. Here, again, if the installation is being done by a company like Tata Power, they will usually first look at your sanctioned load and only proceed if it is appropriate.

Read: Six Questions to Ask About In-Home EV Charging

At the end of the day, your access to regular charging—and at what prices—can be make-or-break for your EV buying decision.

Charging and driving on the highway

The value proposition of an EV is strongest as a city vehicle, as I mentioned earlier. But that’s not to say they aren’t usable for outstation travel—it all depends on the vehicle, how far you need to go and the availability of charging.

First, we need to talk about range. “Range anxiety” is a term that frequently comes up, but many now point out that the main concern is charging speed and access to fast chargers on the road. You don’t worry about the “range” of a petrol or diesel vehicle because you can fill up in a matter of minutes and fuel stations are widespread.

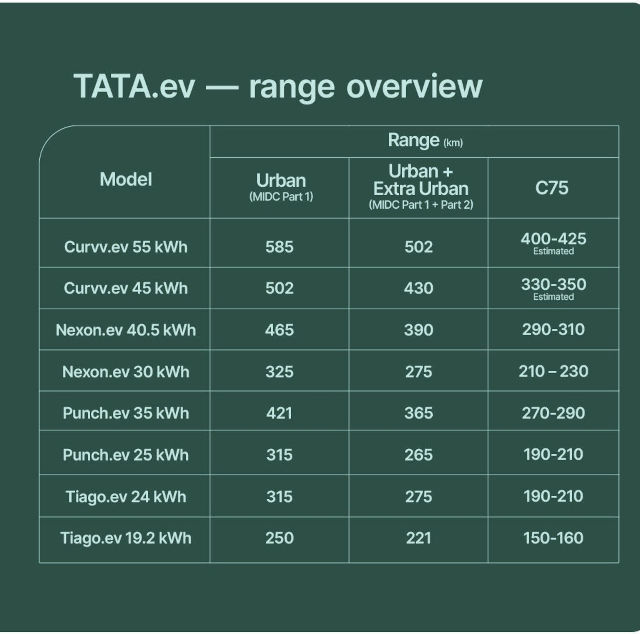

That said, the range of a car on a single charge dictates how convenient or difficult highway drives can be. And I must warn you, how range is marketed is extremely misleading.

The officially certified range of an EV is obtained in highly unrealistic conditions and real-world range is often drastically different. (This is true for both electric cars and scooters, but our focus is cars in this section since we’re talking about highways.)

Both petrol and electric cars are tested by the Automotive Research Association of India in what is known as the MIDC, or Modified Indian Driving Cycle. Cars are tested for fuel economy, range and emissions (whichever apply) on a flat road, with no wind, at a maximum speed of 50 kmph, with only gentle acceleration/deceleration, with the air conditioning off and outside temperatures being less than 30 degrees Celsius.

I don’t need to tell you that this test meant to replicate an Indian urban environment does anything but. (This is also why a petrol car’s marketed fuel efficiency doesn’t match real usage.) There’s also a highway section to the test, which is the same except that the top speed is 90 kmph.

An EV certified for 500 km of range might give less than 400 km in reality. This is an issue with testing standards not only in India, but also in China and Europe, with only the US norms being reasonably realistic.

The Indian guidelines last month changed to include more parts of the tests for EVs, so manufacturers have revised their marketed range down. It’s still unrealistic, but Tata Motors—hidden in a press release—provided a handy table with the old official range, new official range and the company’s own estimates for realistic range.

[Table from a Tata Motors press release on 31 August 2024, showing officially certified and real-world range for its electric cars. This chart is specific to Tata cars, but it should give you a good sense of how to estimate the real range of an EV based on the official numbers.]

Coming back to our topic of highway driving and Ashwin in Noida. He mentions that, since his parents are now retired, the family takes far more frequent road trips than they ever did with a petrol car. His MG ZS EV has a real-world range of 320-340 km, depending on driving conditions, and they mostly travel to locations within 200-250 km from home.

What helps him is planning ahead of time. He mainly uses an app called Plugshare, which lists public chargers on the map. EV owners in India and around the world fill in details about charger availability, cost and rate chargers and networks. Ashwin looks at high speed chargers available on his route or at the destination and marks a few options on Google Maps for him to refer to as he’s driving.

He also has very strong preferences for which charging networks he will use. Charger reliability is often a big concern on highways in India. Especially when it comes to points set up by state-owned oil marketing companies and a bevy of small brands. Chargers might be broken, poorly maintained or disconnected.

A few operators like Zeon in the south and Statiq have gained a reputation among enthusiasts as reliable options.

“Statiq has a phenomenal network, I only charge at Statiq points,” he says; he keeps Tata Power as a backup option. But in general, if a route doesn’t have a Statiq charger, he doesn’t have the confidence that other operators will be good enough to rely on.

But where there is one, he’s happy to stop and wait. It usually takes 40 minutes or so to fast-charge his car up to 80%, while he and his parents take a break at a nearby Starbucks or McDonald’s.

A drive to Dehradun and back costs him about Rs 2,000, including charging at home before setting out and charging along the way (usually for Rs 20-21 per unit).

Most charging networks have their own apps and allow you to scan a code at a charger to start a charging session and then pay online. EVs in India, except for the very high end, offer charging speeds of 40 to 55 minutes to go from 10% to 80% at DC fast chargers. Beyond 80%, charging speeds decline rapidly and it usually isn’t advisable to keep charging, since the remaining 20% can take another half an hour or more.

One annoyance for highway EV drivers is that every network having its own app is inconvenient. Companies like Pulse Energy are trying to solve that, says founder and CEO Akhil Jayaprakash. “Right now, the experience is bad. Chargers don’t work or someone’s already using it when you get there,” he says. “And you need a different app for every CPO, everyone wants to own the customer.” (CPO stands for charge point operator.)

One project his startup is involved in is the Unified Energy Interface, a government-backed plan to let anyone charge on any network using any app. Think UPI for charging, but also for the sale of energy between discoms and network operators and more.

Pulse Energy has also built the MG eHub app in partnership with MG Motor. It allows drivers to see chargers across the country and get real-time availability. It’s targeted at owners of the company’s vehicles, but for now at least anyone can download and use it.

Fast charging, however, brings us to the next question that weighs on most EV buyers’ minds.

Battery wear and care

The battery is the most expensive component of an EV. It can range from 30% to 40% of the bill of materials of a car or scooter.

Lithium-ion batteries are also essentially consumable parts, in that they will eventually wear out. This is something we’re quite familiar with when it comes to phones, which lose charge in two to three years of heavy use, but may be concerning for a vehicle.

How should you take care of your battery so that it lasts as long as possible?

The simple answer—for most people—is that you shouldn’t worry about it. Unlike a phone battery, which is heavily optimised for energy density at the cost of longevity, modern EV batteries use lithium-ion chemistries that are focused on lasting many years.

EV makers in India usually offer a battery warranty of eight years or 150,000 km or so on cars, and five to eight years or 60,000-80,000 km on scooters.

Estimates vary, but the average Indian car owner drives about 10,000-12,000 km in a year. Many who only drive in the city will likely do even less. If that’s you, battery wear will be more a function of time than about how much you use it. You should take the number of years of the warranty as the minimum the battery will last—contrary to often misinformed claims that the battery needs to be changed at the end of eight years.

If you’re someone who drives a lot, to the tune of tens of thousands of kilometres every year, then the battery wearing out sooner will be something to think about. You can use the warranty coverage as a starting point, but do note that the batteries for longer-range cars can actually last a lot longer than the 150,000 km the manufacturer is willing to guarantee.

An owner of an MG ZS EV earlier posted on the Team-BHP forums that he’s driven 118,000 km in two-and-a-half years and the battery health was at about 96%. (Manufacturers usually don’t give this information on the dash, but you can request it from the service centre.)

All that said, here are a few practices I’ve curated that you could follow around battery care, based on my own research and diving into the fine print of the car user manuals:

- Don’t let the charge level drop below 10% on a regular basis; ideally plug in when you hit 20% or so.

- Every once in a while, let the vehicle charge slowly (i.e. on a home charger or slow public charger) all the way to 100%. This lets the battery management system equalise the charge across all cells in a pack.

- Don’t fast charge the vehicle all the time. Fast charging will wear out the battery a little more than slow charging; don’t be scared to fast charge when you need it though.

These are only thumb rules balancing care and convenience, and for those keen on truly optimising their battery wear, we’ll have some resources linked below in the Dig Deeper section. There’s a whole lot more that can be discussed about lithium-ion batteries and different chemistries and how they wear out and react to charging.

But good vehicles today have sophisticated software and battery management systems, which actively work to preserve battery health, so most drivers should be fine so long as they stick to the basics.

”For most EV drivers, battery wear will be more a function of time than how much you use it. One should leave managing batteries to the vehicle.”

[Image source: Hyundai.]

A note of caution: For some Indian brands, there may be teething issues or faults with the power electronics and battery controllers, etc. Without trying to single out any brand, several Tata owners have complained about errors popping up on their car dashboards around high-voltage system faults, requiring a visit to the service centre and a replacement under warranty. Similarly, in scooters, Ola owners have famously had many complaints about batteries, software and more. (Of course, there are also Indian brands like Ather that have been acknowledged for their excellent engineering.)

Eventually, once the battery has worn down, one can return it to a service centre for disposal. The government has notified guidelines on battery waste management and recycling, with the onus being on manufacturers under what it calls Extended Producer Responsibility.

That also brings us to the question of resale value. An EV bought today will likely lose value as technology improves and also as its battery wears out. For many vehicle buyers, that’s a big concern, and the honest answer is that only once thousands of used EVs hit the market a few years down the line will we be able to tell.

The only indicators we have are markets like the US, where EVs have sold in large numbers and now many are on the used market. There, used EV prices have been described as being in “freefall”, dropping in some cases 35-40% over the past couple of years as prices drop on new models.

For today’s buyers in India, that’s a problem they will worry about later.

“There’s a growing class of Indians who are ready to spend on indulgences. They aren’t thinking about ROI, it’s more about an experiential buy,” says Autocar India’s Sorabjee. “Some of the bestselling cars today don’t have great resale value.”

“I’m not worried on the battery front,” says Ashwin, the venture capital investor in Noida. “In any case, we’re not looking at flipping the car, because it’s a nice car we plan on owning for a few years at least.”

Nikhil in Mumbai is similarly unfazed. “I’m someone who’s really into technology in general, so when I decided to get a car, an electric seemed like a natural idea,” he says. Five or six years down the line, he’ll see how the battery holds up. “It was kind of an impulse buy, so I didn’t really compare it to any petrol car.”

Dig deeper

- Read | Changes coming to EV technology and economics in the next few years (Read time: <1 min)

- Read | How to choose the right electric scooter: A buying guide, by C S Swaminathan, Founding Fuel (Read time: 5 min)

- If you want to compare costs between specific petrol and electric models, these Google Sheets should help.

- For cars: Cost: Petrol car vs EV

- For scooters: Cost: Petrol scooter vs EV

- Watch: Mumbai to Goa in an MG ZS EV, from Autocar India, which should give you a better sense of how a 12-hour, 600 km road trip goes in an EV. (~14.5 min)

- Watch: How To Ruin Your Electric Car’s Battery - LFP Edition!, by Engineering Explained, which—contrary to the title—explains for the technically minded how to optimise your battery’s lifespan. (~18 min)