[Tian Shan mountains. Pictures by Team Quipper]

The immigration officer at departures, Indira Gandhi International airport, New Delhi, blankly stared at me. “You have no visa to where you are going?” he barked.

My young colleague Saawani who had reached the adjoining window to get her passport stamped, helpfully called out, “Yes, there is no visa required to go to Kazakhstan, for up to two weeks.”

Fifteen minutes later, the two of us were still waiting to be stamped, while Mr. Officer had gone off to confer with his superiors somewhere. Our other colleagues—we were traveling together on our company off-site—had been lucky in their random choice of immigration desks. They were in duty free already.

He was back finally, grumbling to the adjoining booth, “But there was no updated instruction under K, how was I to know?”

Handing our passports back, he muttered, “Whoever goes to Almaty? Indians prefer Thailand.”

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

At Quipper, we are perpetual wayfarers. As qualitative research practitioners, our work takes us to all sorts of destinations mainly within India. Religious towns of Haridwar and Madurai sometimes, at other times, we have even been to towns such as Jaunpur or Ghazipur where retail stores sell real guns.

When it comes to our off-sites, we love to seek out spaces less trodden outside India. Where we delight in engaging with unworldly locals, uncontaminated with a continuous and blase brush with tourists. In the process, we renew our appreciation of one another within the team as essential parts of a single whole.

Five years back, pre-Covid, our team had travelled to Uzbekistan. Namely the towns of Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara. Each destination had been more compellingly dazzling than the other, with its centuries old architectural heritage standing testimony to the zenith of artistic, intellectual and military life.

Here we were again, heading to yet another Central Asian country, to yet another ancient city—the one called Almaty. Earlier called Verny in the late nineteenth century, and later Alma-Ata when it was part of the Soviet Union in the twentieth century, the city is situated in South-East Kazakhstan, three-and-half hours due north of New Delhi by air.

My first impression of the city was of surprise and truth be told, befuddlement. How could a place be both so spectacularly beautiful with the stretching-into-infinity Trans-Ili Alatau mountains standing at guard on the southern side of the city, as well as so boringly Soviet modernist in its architecture? From any spot in the city, all we had to do was turn around, to seek out the breathtaking snowcapped skyline benignly looking down at us.

[Breathtaking view of the city of Almaty and its snow-capped mountains.]

Equally, and up close, there was no getting away from the yellow Stalinist concrete blocks of its squat residences and dull official buildings. Where were the ancient and grand tiled domes and polygonal chambers of the madrasas, mosques and mausoleums as in Uzbekistan, also a Soviet republic in its time?

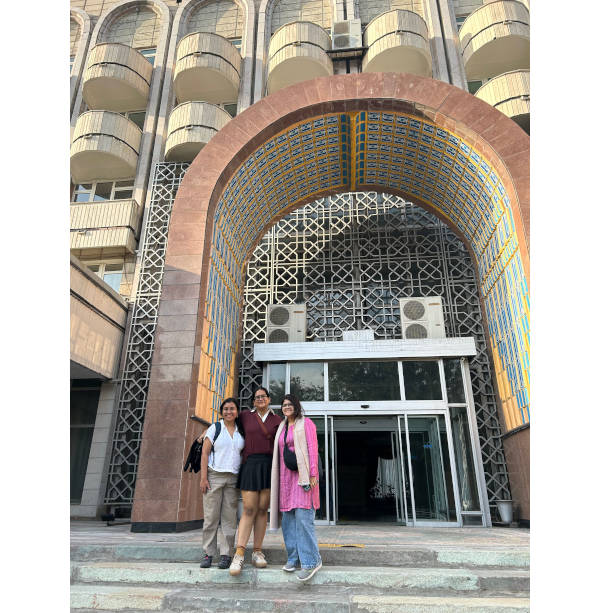

[At the iconic Otrar Hotel, one of the earliest Soviet hotels in Almaty]

Earthquakes, we were told, were to blame.

The Almaty terrain has always been prone to tectonic shocks, situated as it is, atop fault lines of 27 tectonic plates. In the light of this ongoing seismic hazard, the main structures that continue to survive are those built in the mid twentieth century, often with Japanese quakeproof technology. Such as the Academy of Sciences, the Opera House and the crown-headed skyscraper, the Hotel Kazakhstan.

To me, what defied the compelling sameness of these manmade structures and made it really attractive was the very interesting limestone used for its vast walls. Encrusted with ancient seashells, each textured block of ‘limestone concrete’ was distinct. The material is testimony to the ancient 200 million year old Tethys sea that undergirded the landlocked area that is Kazakhstan today, through the unique oceanic creatures frozen forever in it.

[A close up of the wall of the Academy of Sciences, with seashells dating back 200 million years]

The city itself is laid out in a grid-like pattern, each lined with an ‘arak’, a gurgling stream of water that flows down from the mountains. The araks feed the treelined avenues providing a dense green and autumnal rust colour cover across the charming streets of the old town, called the Golden Quarter.

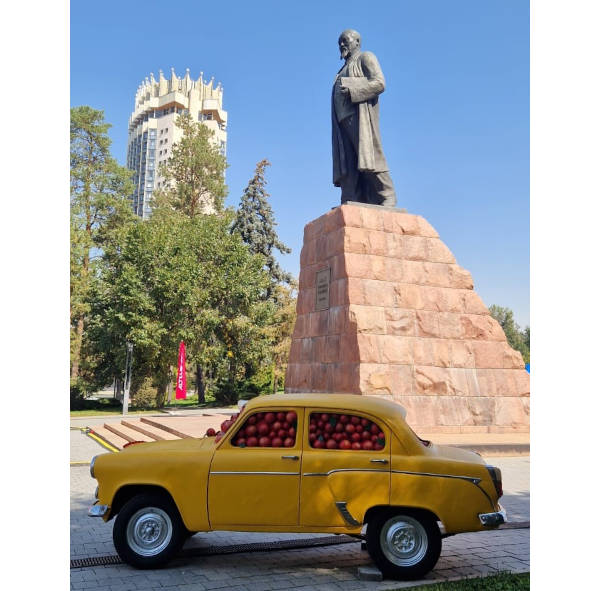

At one of the main intersections in downtown Almaty, stands the tall imposing statue of Abay. Abay or Abay Kunanbayev is known as the crowned poet of Kazakhstan. Young Kazakhs such as our very hip tour guide Azhara, who was taking us around the main sights, are far more scornful of Abay. Azhara believes, he never really appreciated the pastoral and bucolic beauty of Kazakhstan, and instead was an unctuous old man who castigated his fellow citizens for not emulating the progress and emancipation of Europe and neighbouring nineteenth century Russia. He was also known to have denounced the rich oral traditions of local ethnic communities. Needless to say, once Kazakhstan became part of USSR in the early twentieth century, the late Abay was institutionalized as a great Kazakh thinker by the Soviet establishment.

[The statue of Abay Kunanbayev stands tall at one of the main intersections in downtown Almaty, with Hotel Kazakhstan in the backdrop]

Nearly a century after this veneration, Abay appears to have the recurring and uncanny ability of being at the right place, and at the right time, to continue to remain in the news. It was near his statue in Moscow that the clarion anti-Putin call went out in 2012 that became known in social media as #OccupyAbay. The lifeless statue just happened to be the anchor to the sit-in of thousands of protesters.

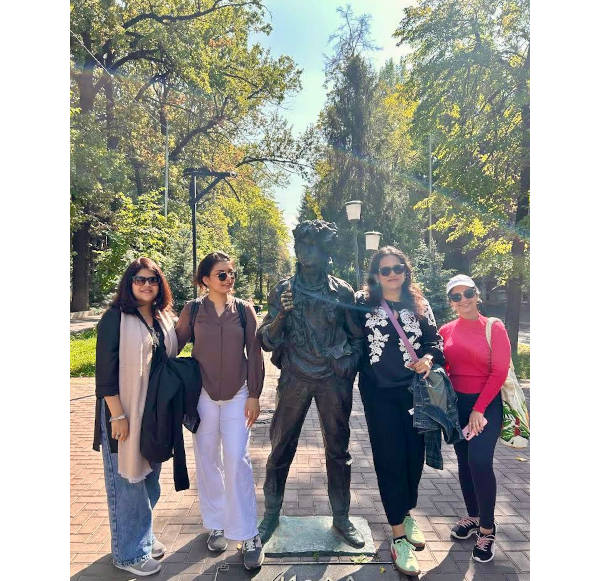

Almaty also has the statue of Viktor Tsoi. At ground level, and endearingly made to size, the diminutive Tsoi, often called the last Rock Hero of the Soviet Union, stands with his feet apart, a lit lighter in his hand, as if beckoning people to follow their inner calling. When the capital city of Kazakhstan got renamed to Nursultan in 2019, the youth of Kazakhstan put up a ‘change’ banner of protest on this statue, to register their disgust at the hagiography of a living Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev. (The capital city is back to being called Astana once again, since 2022).

‘Khochu Peremen’ is one of Tsoi’s most famous songs and is an anthem for all rebellious youngsters. We are awaiting change, translates the words written by Tsoi. Forever young—he died at the age of 28 in 1990 even before the break-up of the Soviet Union—Tsoi remains an abiding polestar to a young Kazakh cohort that seeks liberation from the beliefs and shackles of an older dogmatic generation.

[Quipper’s Gen Z team with the statue of Soviet rock legend Viktor Tsoi, whose anthem 'Khochu Peremen' continues to inspire a new generation's call for change]

Tsoi’s grandparents were Koreans who were deported into Kazakhstan by Stalin. Stalin had signed a decree in some xenophobic fervour, and 172,000 Soviet Koreans were forcefully transported from the East coast of the Soviet Union, in packed railway wagons across 6,400 kilometres, to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in 1937. Young Kazakh Koreans today strive to find their identity within the combination of both locations—Central Asia, which is the land of their birth, and South Korea, where they ethnically originate from. In current times, Almaty is peppered with K-pop stores and Korean food outlets, much to the delight of our Gen Z team members. Equally popular is the indie music scene in the city, where protests against the establishment and activism takes the form of art—via music and poetry.

[Our Team Z in front of K-Pop stores in Almaty]

In fact, Kazakhstan is a land that is a combination of ethnicities, a melting pot of medieval tribes and more recent migrants. It is one of the few countries in the world where a citizen’s ID has an additional column on ethnicity. Although 65% identify themselves as Islamic, decades of being part of the USSR has relegated religion to the back burner. At best, a moderate form of Islam is practised. One of the main ethnic groups are the Uyghurs, free-living migrant nomads from China, who follow a more Sufi form of worship. Their practices have remnants of Shamanism, Buddhism and many other influences.

Those who live in Siberia or Northern Alaska, I have heard, have an array of words to describe every kind of snow.

Kazakhstan, in the same vein, has words and words to describe various groups of migrants who have made it their home over millennia.

Uyghurs, numbering over 300,000 could be the yarliks who came to the land in the late 19th and early 20th century; the ‘newcomer’ keganlars came in the 1950s and ’60s. Or the most recent kitaliks who recently arrived in 1997, from China.

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

Part of our week-long trip was an excursion to the sacred Tian Shan mountains further east. On our way, we passed through multiple horizons of craggy and uneven terrain with herds of cattle visible as far as the eyes could see. Hundreds of horses, plenty of sheep and cows were grazing across the rough mounds of hills and vales. Every single mile was spellbinding—like an artist’s impression of a unique composition of stark nature.

[The majestic Tian Shan mountains, with grazing cattle and stunning natural landscapes]

Sporadically, we would pass a village. Our escort driver pointed out gates of homes that were wide open, although it was early dawn, just after daybreak. This, he said, was a sign of the gate belonging to an Uyghur home as versus local ethnic Kazakh homes. Resident Uyghurs woke before dawn, and opened their gates, or their tents to worship the morning, and welcome peace and prosperity into their lives.

Uyghurs, unlike most of the Korean Kazakhs, do not fancy working in cities, or getting a higher education. Being in cities is not a sign of progress. ‘Why be a pen-pusher in a government office when you can be a free shepherd!’ is their underlying motto.

Unlike the uniformity of Almaty’s architecture, the Kazakh village is diverse and fiercely attractive. Based on whosoever lives in it. Ethnic Kazakhs, Uyghur migrants, ethnic Russians, Mongolians, or Koreans. Peppered with open gardens, chicken coops, a mosque or two, the freshest vegetables and fruits you will see anywhere on sale, there is an unspoiled pastoral continuity. I imagine it would have looked and felt exactly the same had I visited a few hundred years ago.

There is change of course. Like hearing the same old Samsung or OnePlus ringtone and notification sounds in the most unlikely of sparsely populated places among locals. Quite disconcerting.

Kazakhstan is huge—almost as widespread in size as India, yet has just 20 million inhabitants in all. Imagine that: less than the population of our city of Mumbai. It is one of the world’s top grain producers, and is abundant in oil, copper, uranium, and many other rare elements such as tungsten and titanium. In 2023, Kazakhstan’s trade surplus was 20 billion dollars. India might have a far larger economy and we certainly cannot boast of a surplus. In the same year, we had a deficit of 248 billion dollars.

The multi-ethnic inhabitants reflect and echo the diverse geographical composition of this breathtaking land that is a geologist’s dream come true. Ancient Archaean (over 2 billion years old) to more recent Quaternary (last 2.5 million years) deposits, thousands of miles of mountain-fed streams—this most ancient land has remained pristine and still feels unsullied and unexplored.

Some 8,500 rivers criss-cross the land. The main rivers all join up and fall into Lake Balkhash. Here is one country where the rivers lead not to any sea, but to a ‘lake’. A lake that covers 16,400 square kilometres, being an ‘endorheic basin’.

Very noticeable on the highways were the sporadic yet sprawling cemeteries. While earthquakes may have brought down larger structures everywhere, the beautiful tombs in the burial grounds remained intact. This is a land where in death is promised a permanent and deified resting place, never to be disturbed. With an abundance of land, there is no compulsion to ‘turn over’ burial grounds preparing for the next set of burials, as it is unfortunately in India, for those who do not cremate. Here in Kazakhstan, the departed truly rest in peace.

[Kazakhs do rest in peace. Tombs at graveyards have outlived buildings in quake-prone Kazakhstan]

Burials in Kazakhstan date back to the Bronze age. Called kurgans by archaeologists, Kazakhstan has a rich find of ancient sites that continue to be discovered. Perhaps the most famous is the Golden Man, dug up in 1969, of a young prince (or princess) buried in a golden suit of armour, dated to the third century BCE that was the Scythian Era. The clothes and headdress were embroidered with gold plaques intricately designed, and there were winged horses on his crown. Exquisite.

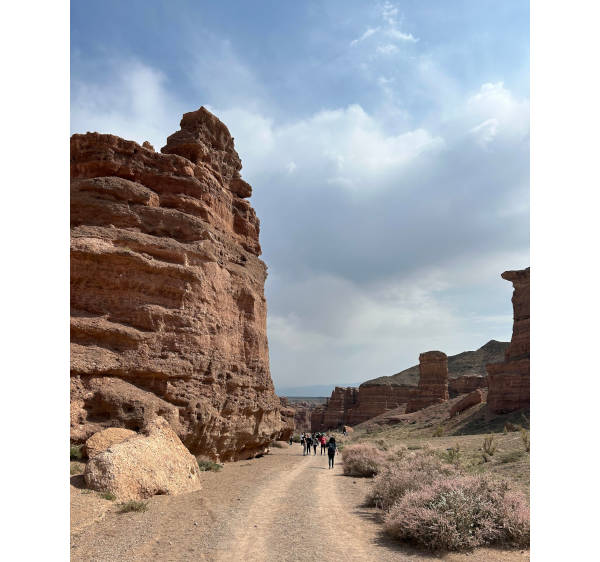

From Almaty, we had been spoiled for choice about the direction to explore outwards. We settled for going towards the Charyn Canyon and the Kaindy lake, six hours’ drive away, both promising excellent treks and rugged hiking trails. Charyn is simply an astonishing land formation.

[Charyn Canyon, with an unbroken geological record going back millions of years]

German researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry have analysed samples from the canyon, producing a five-million-year “unbroken” geological record of rainfall and climate change in the region. Surrounded by the jagged beauty of the canyon, I marvelled at the grandeur that was even more stunning due to the rather limited number of tourists. In fact, most of us came back with our budget for souvenirs unused. Kazakhstan continues to treat tourists, a recent import, with puzzlement.

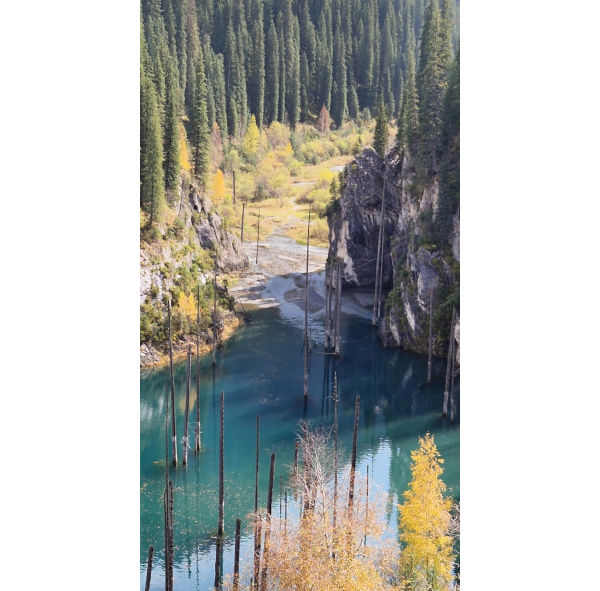

[Kaindy lake: The sunken forest lake formed after an earthquake in 1911]

And what can I say about the startlingly aquamarine Kaindy lake? Situated 2,000 meters above sea level, the deep lake had formed at the base of two majestic mountains that were cut off at either end of the valley by landslides during an earthquake in 1911. This created a sunken forest lake where the ancient fir tree trunks, no longer living, continue to stand upright through the seasons in the water or ice. The incredible beauty of the lake is to be seen to be believed.

[The team at Kaindy lake]

Running around in mad delight, we got to experience our first hailstorm in these mountains—a steady drumming of millions of marble-sized round ice formations.

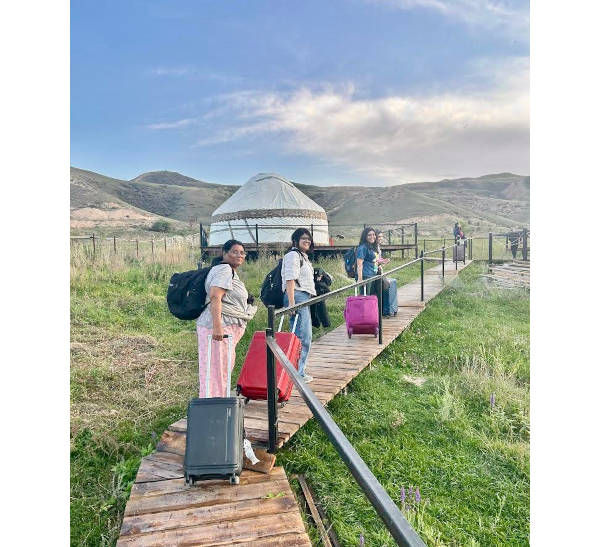

Our team of ten lived in three ‘yurts’, the round tents insulated with felt and used by nomadic tribes, during our trip to the Tian Shan mountains. Yurts are a distinctive feature of Central Asian life through the last few thousand years.

[The yurt: a distinctive symbol of nomadic life, the tent embodys tradition and the spirit of the vast grasslands]

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

As a team, we women at Quipper follow the ‘work-from-anywhere’ as our business model. With no office that we attend together daily, we treasured being with each other at Kazakhstan. As Pia, my business partner put it, “Impressive, that it can be so smooth to travel as a pack of ten.”

So where do we go next? Perhaps another Central Asian country of the ancient silk route. Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan. So many unexplored places to choose from.

I would love to go back to Almaty. To continue to explore the land in other areas not yet ventured, heading out in different directions. The Shymbulak mountain resort maybe. Or the Korgalzhyn Nature Reserve. Go camping across any of the scores of options in the rugged terrains gradually coming on the map. I would love to participate in the ongoing archaeological ‘digs’, or at least visit some of the ancient kurgan mounds.

There is one more reason I wish to go back to Almaty. That's the Arasan spa. Epiphanic. But that is the subject of a separate story.

Know Before You Go

[A picnic lunch on the Kaindy Lake trail]

How to get there

- Astana is the capital city, but I recommend Almaty as the destination to go to.

- Direct flights available from New Delhi: Indigo and Air Astana, to Almaty. Around Rs. 30,000 for a return ticket

Where to stay

- Plenty of options. We suggest Renion Residences—suites with kitchenettes, where three members can stay in each unit, comfortably

- The iconic Almaty landmark, Hotel Kazakhstan—a quake-proof high-rise with a crown atop

What to eat

- From vegans to adventurous meat eaters, there are options for all. Our vegan survived on salads and French fries.

- Georgian, Turkish, Korean options easily available. Kazakh food is quite delicious, although I steered clear of horsemeat

Major attractions

- Kok-Tobe hill for a panoramic view of Almaty city. Go up by the funicular

- City tour of modernist Soviet era buildings within the treelined grid of Almaty city, nestled near the snowcapped mountain range

- Ascension Cathedral, an Orthodox church built entirely of wood, and with beautiful interiors

- Arasan spa

- Golden Man Museum, Turgen Gorge

- Excursions in all directions into the geological marvels of Kazakhstan—Charyn Canyon, Kaindy Sunken Forest Lake in the Tian Shan mountains, Shymbulak mountain resort

[At the Ascension Cathedral, Almaty]

Best time to visit

- Autumn. August-September

- And if you would like to brave it, early winter. October-November

[The graphics inside Almaty’s public transport puzzled us. Why show at upper-right ‘no rabbit’? We later learnt that rabbits referred to ticketless travellers]