[From Unsplash]

With research and inputs from Kriti Krishnan

In March 2018, I was mentally unstable on the first day of a new assignment as visiting faculty at Anant National University in Ahmedabad. Previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder, I was hypomanic as I taught a class of postgraduate students. To me, the class felt magical and immersive, but the next day, I left my assignment mid-way, and did not come back to complete the module.

Yet nearly five years later, my engagement with the university has deepened. I teach a class called ‘Netflix and the art of design writing’ to two cohorts of undergraduates and postgraduates. In August, they invited me to speak at their first TEDx conference. To celebrate World Mental Health Day in October, I gave a talk on ‘What I wish I knew about mental health in my 20s’ to a packed hall of students.

So how did this turnaround happen? How did my potentially short-lived teaching career resurrect itself? Mainly because senior management understood the nuances of mental health, and decided to give me a second chance. “It’s not that I’ve had a lot of experience, but I have somewhere got it in my head that mental illness is like heart disease or diabetes or endometriosis or joint pain that comes and goes, and people live with it. And there are phases when it’s bad, and there are phases when it’s ok,” says Pramath Raj Sinha, a higher education pioneer, and the person who had initially asked me to teach at Anant.

Garima Aggarwal, the head of the programme I was teaching on, also realised I wanted to teach and gave me a short trial assignment when I had recovered. When I was able to complete that, they invited me back onto the regular teaching programme in 2019. And I’ve been there ever since.

Compare this story with Prerna’s (name changed), a lawyer in her mid-20s. She joined a law firm only to realise it was a toxic work environment. “The general work culture of the organisation was each one for themselves. It was a culture of prioritising yourself over the needs of the team, throwing someone, especially juniors, under the bus, even if it was your own mistake. Also, there was a need to be available 24/7, no matter what time of night or day it was, even in cases of personal emergencies. And finally, seniors would raise voices and shout at people very vocally, in a large setting, for small issues, using unacceptable language, rather than someone telling you off privately,” she says.

She left the law firm and started therapy to attend to her mental and emotional well-being. “I was constantly anxious. Not feeling good enough was a dominant feeling. I was severely burnt out also after this experience. It was not a sustainable lifestyle to work in this environment. It’s left a bitter taste in my mouth about law firms,” she acknowledges. Most of her colleagues have also left, she adds.

The first story is a case study of how leaders can successfully manage an individual with a serious mental health condition in the workplace. The second story is about how a toxic work environment can damage one’s mental health. Unfortunately, it takes little to guess which one is more common. So, I would like to ask: who is responsible for emotional and mental well-being in the workplace? A particularly relevant question, post-pandemic, as we emerge from two challenging years, and return to an evolving workplace.

The toxic Indian workplace

Let’s first look at the data. In a September 2022 report on ‘Mental Health and Well-being in the Workplace’, professional services firm Deloitte points out that in its survey of nearly 4,000 white-collar workers in corporate India, “more than 80 percent respondents reported being affected by at least one adverse mental health symptom, while more than 65 percent reported at least two symptoms, and over 50 percent indicated three or more such symptoms.” Symptoms include depression, emotional exhaustion or burnout, irritability or anger, sleep issues and anger. Workplace stress was the number one source of stress, according to the report.

“We estimate that poor mental health amongst employees cost Indian employers ~INR 110,000 crore (~US$14 billion) over the last year,” due to the cost of absenteeism, presenteeism and cost of employee turnover, concludes the report.

Consulting firm McKinsey offers similar insights. In an August 2022 article, Employee Mental Health and Burnout in Asia: A Time to Act, senior McKinsey partners Alistair Carmichael, Erica Hutchins Coe and Martin Dewhurst caution that “Indian respondents expressed elevated rates of every outcome—burnout, distress, anxiety, and depression. For each outcome factor, around four in ten respondents reported symptoms.” That’s 40% of the Indian workforce with poor emotional and mental well-being, more than other Asian countries.

The number one culprit of poor workplace mental health, according to the McKinsey report? Toxic workplace behaviour, defined as when ‘employees experience interpersonal behaviour that leads them to feel unvalued, belittled, or unsafe, such as unfair or demeaning treatment, non-inclusive behaviour, sabotaging, cutthroat competition, abusive management, and unethical behaviour from leaders or co-workers.’ It is the dominant reason for burnout, depression, anxiety and distress in the Indian workplace.

In a patriarchal and hierarchical society such as ours, the prevailing stereotype is that the toxic boss gets results. Yet the negative impact of this way of working is huge. “You can have a person who is extremely toxic to his subordinates but he knows how to manage his or her bosses. It creates a very mediocre organisation, where everybody is just protecting themselves, there is a feeling of fear that toxic bosses will make life difficult for you. Fear kills innovation. There is no dissent, you can’t breed creativity. And it creates that environment of a very sad work environment where people are just living pay cheque to pay cheque, clocking in nine-to-five,” observes Nidhi Dhanju, group chief human resource officer at engineering company Praj Industries.

Introducing a pentagon of emotional and mental well-being at work

Prerna experienced toxicity, whereas I experienced support, compassion and empathy. Is it only leadership that makes the difference to emotional and mental well-being at work? Who is responsible, and in what way? What does emotional and mental well-being even look like in the workplace?

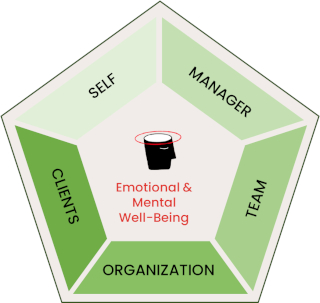

My colleague Kriti Krishnan decided to research workplace mental health. Our insights, combined with my two decades’ experience of writing about workplaces, and living with a mental health condition, led us to creating a simple framework to address the issue of emotional and mental well-being, as below.

We believe it is important to have key workplace stakeholders aligned on the issue of emotional and mental well-being. These include: the individual employee, the immediate manager, the team, the organisation—and the client. Each of them plays a specific role in creating a work atmosphere that fosters mental and emotional well-being at work.

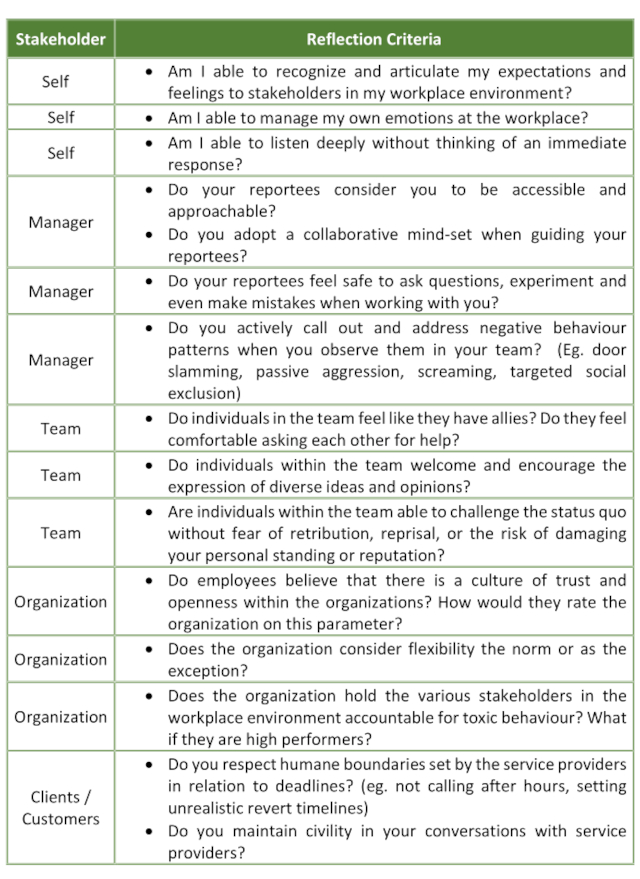

As the above figure suggests, alignment between the individual stakeholders is vital, otherwise the pentagon ends up being lopsided. I believe mental health is a team sport. It is not something that can be achieved in isolation. Like a cricket team, no one person—not the captain, batter, bowler, fielder or coach—is solely responsible for ongoing success. So Kriti and I created an accompanying toolkit that can help companies assess if, and how, each stakeholder contributes to emotional and mental well-being at work, and whether all are aligned to create a positive, supportive work environment. A set of reflection criteria encourage exploration and discussion on this topic.

Aligning five stakeholders

To start, we felt it is important to recognise the role of the individual (“the self” in our framework). This could be any individual, at any level in the organisation. We all need to take responsibility for our mental well-being at work, by managing our thoughts and emotions, and our responses to external situations and stimuli, whether or not those are in our control. Being able to articulate one’s expectations to key stakeholders helps us feel psychologically safer at work, and can reduce sources of stress. Listening deeply, versus listening only to reply, is also a highly undervalued organisational skill. All of these contribute to individual sense of well-being, and have a ripple effect throughout the organisation.

For example, over time, I have come to realise just how much work-related stress is a trigger for my mood swings, and how I need to take responsibility for my mental health. Too much work makes me stressed, too little work makes me depressed. I’ve reached a place where I can manage myself much better than earlier, by calibrating my workload, sharing my expectations with my colleagues and thereby preventing stress and anxiety from accumulating to a breaking point.

Second, the relationship between the manager and the individual employee, possibly the most important factor in our pentagon. The reflection criteria in our table highlight how critical it is for managers to be seen as approachable, accessible and collaborative, even when their juniors make mistakes.

For example, before I joined Anant, I had flagged my bipolarity to Pramath, by telling him that I had a chronic mental health condition and that there could be trouble with schedules and deadlines. Although he wasn’t sure what to expect at the time, he thanked me for informing him. The conversation helped me to feel more secure that if there was an issue, he would support me.

Third, the team. The reflection criteria explore whether team members work as allies with each other, or whether each member is an island within the team. Being able to ask for help from one’s colleagues, to express diverse opinions, and to challenge the status quo are all huge contributors of emotional and mental well-being.

A proxy for allies is the importance of having a friend at work. In a column titled ‘Why you should make friends at work,’ for the MIT Sloan Management Review, leading organisational behaviour thinker Lynda Gratton writes that “Friendships at work matter. When so many hours are spent working, having someone who understands our situation—the players involved, the office dynamics, and the general organisational culture—can help buffer routine stress. When we share our experiences, it often reminds us that others have gone through similar ones. Gallup research found that agreement with the statement ‘I have a best friend at work’ is a strong predictor of whether you are likely to stay in your job,” she writes.

Fourth and the most intuitive: the organisation, defined by the role of leaders, HR and the culture itself. Emotional and mental well-being is a direct result of many parameters defined by senior leadership, especially toxic workplace behaviour.

Alok Kshirsagar, a senior partner at McKinsey, reinforces that ‘‘toxic workforce behaviour is a leadership issue, a business and cultural issue, not an HR function issue.” Speaking on a recent CNBC TV18 panel on workplace mental health, he emphasised the need to “bust the myth that driving performance and being nice are in opposition to each other. It’s a belief that if I want to get results, I’m going to be extremely demanding, set outrageous targets and yell and scream. The reality is the best sustainable leaders are also the most empathetic and collaborative leaders. Those who are aggressive, they’re not able to sustain. This is our message to top leadership. Don’t average out performance and behaviour. You cannot be a good performer if you’re not also an empathetic leader.”

For Dhanju, HR managers need to “detect and identify patterns” of toxic workplace behaviour, especially amongst high-performers. They should be “empowered to escalate issues” to business leaders, to get them to take appropriate action, such as asking offending individuals to leave.

Finally, clients. Workplaces are market-facing and companies operate in a competitive world, which is why we included clients and customers in our framework. Maintaining boundaries and a civil tone of voice when communicating are all proponents of emotional and mental well-being, to create a work environment which is dynamic and responsive, but not stressful. As Dhanju says, “people can manage overwork, but they can’t manage stress with the ecosystem.”

So, who is responsible for emotional and mental well-being at work? We all are. Emotional and mental well-being at work is too important to be left to any one individual. We hope our pentagon will help you reflect on your various roles—as individuals, managers, team-members, leaders and clients. Mental health and well-being are a team sport, and it is time we start playing it like one.

Still curious?

Read an extract from Aparna Piramal Raje’s book Chemical Khichdi: How I Hacked My Mental Health

Kriti Krishnan is a team lead at Dasra, where she guides the investment of philanthropic capital, especially in the mental health sector