By NS Ramnath and Charles Assisi

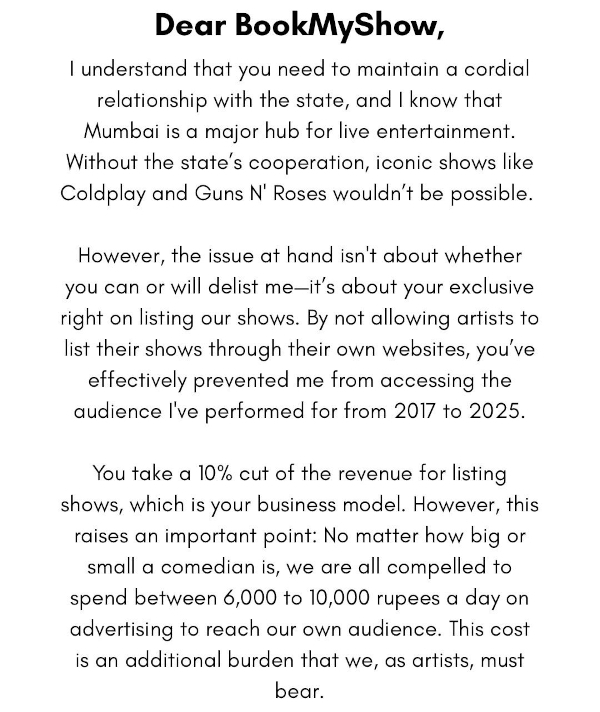

When comedian Kunal Kamra posted a letter on X (formerly Twitter) addressed to ticketing platform BookMyShow (BMS), it instantly drew widespread attention. The company was under pressure to delist him from the platform. Kamra’s post struck all the right chords with the heart.

The outpouring of public support that followed was immediate and deeply emotional. Many rallied behind Kamra, seeing his plea as a stand for artists’ rights in an era where large platforms hold the key to loyal audiences. A stand-up comedian based in Mumbai we spoke to said he stands in solidarity with Kamra. He was talking on behalf of “the fledgling comic community” India has. “And we have bigger problems to deal with than selling tickets on BMS,” he said.

His point is that because the business of comedy is still a very small one in India, people such as him come together under “Artist Collectives”. Most people here would have built their own networks and databases of people whom they reach out to directly such as through email and Instagram, which is their biggest point of contact.

He makes the case that it is usually large movies, singers, plays, and big name artists such as Kamra who are draws on platforms such as BMS. People such as him go unnoticed. “It would be nice to be there because there is an audience who trusts BMS. The friction of booking via BMS is low as well.”

So, what happens to an artist’s data once you get to be a big name and are on a platform? Does it reside with you? Or does it reside with the platform? While the stand-up comic and other artists support Kamra, does it stand to legal scrutiny?

The Bengaluru-based technology lawyer Rahul Matthan told us, “I don’t think Kamra will get this data. It was never his. If he wants to secure this, he has to build the audience himself without piggybacking off the massive infrastructure that BMS has built.”

It was in line with what Supreme Court advocate Nappinai NS had to say. “The data belongs to the platform unless otherwise agreed. The artist on a platform is bound by the contractual terms and unless Kamra’s claims are based on such terms, he cannot sustain his claim.”

This is where the problem begins as well. While our stand-up comic friend tells us he could have been bigger if he had been on BookMyShow, there’s a clash of perspectives. It is more than a dust-up between a performer and a ticketing platform. It is a snapshot of a larger issue that will only become more pressing. Kamra’s letter underscores how modern creators of all stripes place significant trust in platforms that promise large audiences, sophisticated analytics, and marketing muscle. In exchange, they often sign away direct control of the very resource that might matter most: the ability to communicate with their fans without interference.

As this drama unfolds, more questions emerge. And they impact all of us. Who really owns the data we generate when we buy tickets, share social media posts, or sign up for newsletters? Is it the individual, the artist, or the platform that invests in the technology and infrastructure to host these interactions?

These questions are important for us as individuals and also as part of and participants in the society. And they are especially important these days because many of us wear additional hats — as creators. Even if you don’t run a formal business, you still might have a newsletter, a podcast, or a YouTube channel, even a WhatsApp channel. Therefore, questions about data, its ownership and sharing are important to us.

There are no easy answers.

Some of them lie at the intersection of law, technology, business and society at large. So let’s take a look at how each of them is shaping the data landscape.

The law

India created its first major data protection law in 2023, called the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act), with additional rules drafted in 2025. This law protects people's personal information while still allowing businesses to use data responsibly.

The law came after a 2017 court decision that made privacy a basic right in India. It applies to any organization that collects information from people in India.

The system is based on six main ideas that ensure data is collected fairly, used only for specific purposes, kept accurate, and stored securely. It also specifies clear roles for everyone involved: the people whose data is collected, the organizations collecting it, and those processing it on their behalf.

It will make sense to learn the key terms. During our discussions and reporting, we noticed many people using them as if everyone already knew what they meant. We think this trend will continue. So, here's a list of key terms:

Data Principals: Any individual whose personal data is being collected and processed. Simply put, this is you — the person to whom the data belongs.

Data Fiduciaries: Entities that determine the purpose and means of processing personal data. These are the organizations that decide why and how your data will be collected, used, and stored. Example: Banks like HDFC or SBI that collect your financial information to provide banking services. Telecom companies like Jio or Airtel that collect your usage data to provide mobile services. E-commerce platforms like Amazon that collect your shopping preferences to recommend products.

Data Processors: Individuals or organizations that process personal data on behalf of Data Fiduciaries without determining the purpose or means of processing. They essentially handle data as instructed by the Data Fiduciary. For example, cloud service providers that store customer data for companies.

Consent Managers: These are registered entities that act as intermediaries between Data Principals and Data Fiduciaries, helping individuals manage their consent preferences through accessible, transparent platforms.

The Data Protection Board of India is the central regulatory authority established under the DPDP Act to oversee compliance, investigate breaches, and enforce penalties for violations.

Given this context, how do we navigate the data landscape? Here’s a compilation of the tips we gathered while we were reporting and reading up on the issue. We have divided the tips into two segments.

Some tips

If you are an individual

Know and exercise your rights. The law gives you control over your personal data. You can access your information, correct inaccuracies, and even request deletion. Remember that you can withdraw consent at any time — it's not a one-time decision. Some services reinforce this right at regular intervals. For example, Gmail asks for your fresh consent every six months, in case you have given permission for say, Cred to access emails (for easy credit card payment). Not every company does it. So, regularly review Third-Party Apps you might have given access to your social media accounts such as X, and remove any that you no longer use or trust.

Be thoughtful about consent. When you see those privacy notices pop up, take a moment to understand what you're agreeing to. Consent fatigue is real, and you might end up agreeing to share more details than you should. Scan consent pop-ups for key details and hit "decline" or "customize" to limit tracking.

Share only what's necessary. In our connected world, it's tempting to overshare. Before providing personal information, ask yourself if it's really needed. Consider using privacy tools like temporary email addresses for non-essential services and adjusting privacy settings on social platforms to limit data collection. For example, on most platforms you can disable non essential cookies, and you can limit to location sharing only when it’s essential.

Secure your digital presence. Create strong, unique passwords for different accounts and enable two-factor authentication where available. Be cautious about the information you share on public forums — once it's out there, it's difficult to take back. Think of your digital security as you would your home security.

Stay alert to data breaches. Organizations are now required to notify you about breaches affecting your data. If you receive such a notification, act quickly — change passwords, monitor your accounts for suspicious activity, and immediately act (eg, block your credit cards) if financial information was compromised.

If you are a creator or a small business

Build trust through transparent consent practices. Make your data collection notices clear, concise, and honest. Explain in plain language what data you're collecting and why it matters for your service. Avoid burying important details in legal jargon. When you change how you use data, reach out to renew consent — your users will appreciate the respect shown. (It might need some iterations, but it’s worth going through this exercise. When we recently enabled the option for voluntary payments at Founding Fuel, we spent some time discussing how to simply, effectively and transparently convey what happens to the data we collect during the payment process. It was worth the effort, for it signalled to our community that we take data and privacy seriously.)

Treat security as an ongoing priority. Implement strong safeguards like encryption and access controls, but recognize that security isn't a one-time setup. Develop and regularly test your incident response plan. Think of data security as regular maintenance rather than a one-time installation — it requires consistent attention and updates. (If you don’t have a secure system, you might be better off outsourcing data storage to those who already have secure systems in place. Again, it’s one of the reasons why Founding Fuel decided not to store personal data on our servers.)

Handle data breaches responsibly. If a breach occurs, act quickly and transparently. Notify affected individuals promptly and report to the Data Protection Board within 72 hours. Provide clear information about what happened and what steps people should take. Remember that how you handle a breach can either build or destroy trust with your customers.

Manage your data ecosystem carefully. When sharing data with partners or vendors, create clear agreements that specify usage limitations and security requirements. Regularly check that these third parties are honouring their commitments. Remember that you remain responsible for data even when it's in someone else's hands. (Therefore, choose your partners carefully.)

Embrace data minimization as a business advantage. Collect only what you truly need, keep it only as long as necessary, and delete it securely afterward. This approach not only ensures compliance but also reduces your security risks and storage costs. Think of data like inventory — too much unused stock creates unnecessary costs and risks.

The technology

At Founding Fuel, we have been closely tracking people thinking about data for many years now. (The Aadhaar Effect book was an outcome of that reporting.) From our research, we can say that the account aggregator system is a big step in making data collection and sharing easier. It applies only to financial data right now. It's important for us to know how it works, because, as we will see, it has other applications too.

Think of the Account Aggregator system as a trusted messenger that carries your financial data from one place to another, but only when you give permission.

The system works like this.

When you need to share your financial information (like bank statements or investment details) with someone (like a loan provider), instead of manually collecting and sharing documents, you use an Account Aggregator. This AA acts as a secure pipeline that connects your financial data providers (banks, mutual funds, etc.) with entities that need your data (lenders, financial advisors, etc.).

The beauty of this system is that it's entirely consent-based. Your data moves only when you explicitly approve it, for specific purposes, and for limited time periods. The AA itself can't see, store, or modify your data — it's just a secure tunnel. Your information travels encrypted from end to end, making it much safer than traditional methods of sharing financial documents.

It aligns with India's data protection framework, which emphasizes consent, purpose limitation, and data minimization.

Let’s take an example of a hypothetical person. Let’s call her Priya.

How Priya smartly shares her financial data

Priya is a marketing executive who wants to apply for a home loan. Here's how the AA system helps her:

-

Setting up: Priya downloads an Account Aggregator app (like Finvu or Onemoney) and creates an account. She links her various financial accounts — her HDFC and SBI bank accounts, her mutual funds with Kotak, and her insurance policies with LIC.

-

Loan application: When Priya applies for a home loan with ICICI Bank, instead of asking her to submit physical statements and documents, the bank sends a data request through the AA network.

-

Consent request: Priya receives a notification on her AA app. The request clearly specifies what data ICICI Bank wants (transaction history for the last 6 months, investment details, etc.), why they need it (for loan eligibility assessment), and how long they'll keep it (say, 6 months).

-

Giving permission: After reviewing the request, Priya approves it with a simple tap and authenticates with her PIN. She likes that she can see exactly what she's sharing and for how long.

-

Secure data flow: The AA sends encrypted data requests to Priya's banks and other financial institutions. These institutions (the Financial Information Providers or FIPs) verify the consent and send the requested data — encrypted — to the AA.

-

Data delivery: The AA forwards this encrypted data to ICICI Bank (the Financial Information User or FIU). At no point can the AA itself see Priya's actual financial information.

-

Loan processing: ICICI Bank receives Priya's verified financial information in real-time and processes her loan application much faster than traditional methods.

-

Ongoing control: Priya can check her AA app anytime to see who has access to her data. If she changes her mind, she can revoke consent with a single tap, and the data access stops immediately.

The next month, when Priya's financial advisor needs to review her portfolio, she can grant temporary access to specific accounts through the same AA system — no need to download statements or email sensitive documents.

What makes this powerful is that Priya remains in control throughout the process. Her data moves only with her explicit permission, for specific purposes, and she can track or revoke access at any time.

Beyond Account Aggregation

On the surface, it might seem as if Kunal Kamra’s incident might have nothing to do with how Priya got her loan. But, one of the potential use cases that came up during our conversation went like this. As far as we or the people we spoke to know, no one is actually working on a system like this, for various practical reasons. But we are sharing it here just as an example of a potential pathway.

How Priya could curate her perfect festival without planning it

Priya, the marketing executive we saw in Part 1, lives in Bangalore. She loves attending live events. Over the past two years, she's purchased tickets to stand-up comedy shows, indie music concerts, theater performances, and film festivals through various platforms like BookMyShow, Paytm Insider, and venue-specific websites.

Before we proceed, imagine a Ticket Aggregator system that functions as a secure bridge between entertainment consumers and creators, allowing individuals to share their event attendance history while maintaining control over their data. The system connects various ticketing platforms (BookMyShow, Paytm Insider, TicketMaster, etc.) with content creators who want to understand audience preferences. When a creator wants to design a new programme, they can request anonymized or personalized data from potential audience members who opt in to share their entertainment history.

Just like in the financial Account Aggregator system, the Ticket Aggregator never stores the actual data—it simply facilitates the secure, encrypted transfer of information from ticketing platforms to creators, based on explicit user consent. Users can specify exactly what information they're willing to share, for how long, and for what purpose.

Now, one day, Priya receives a notification from her Ticket Aggregator app about a new request. Aakash, an up-and-coming event curator, is planning to launch a new cultural festival in Bangalore and is seeking insights from local entertainment enthusiasts to shape his programming.

-

The request: Aakash's request specifies exactly what information he's looking for: the types of events Priya has attended in the last 18 months, approximate price points, venues she frequents, and general timing preferences (weekday evenings vs. weekends). The request clearly states that this data will only be used to inform the festival's programming and will be deleted after 3 months.

-

Reviewing the details: Priya opens the request and sees a clear breakdown of what data would be shared. She notices she can customize the permission — she's comfortable sharing her comedy and music preferences but decides to exclude theater attendance since those choices are more personal to her.

-

Granting permission: After reviewing and adjusting the parameters, Priya approves the request with her PIN. She appreciates that the system shows exactly which ticketing platforms will be providing her data (BookMyShow and Paytm Insider in this case).

-

Behind the scenes: The Ticket Aggregator sends encrypted data requests to these platforms. The platforms verify Priya's consent and then transmit her specified entertainment history — encrypted — through the Aggregator to Aakash. The Aggregator itself never sees or stores Priya's actual attendance data.

-

Collective insights: Aakash receives anonymized data from Priya and hundreds of other consenting users in the Bangalore area. Using analytics tools, he identifies patterns: a strong preference for intimate acoustic performances on Thursday evenings, comedy showcases on Saturdays, and a price sensitivity threshold around Rs 1,200 for premium experiences.

-

Festival design: Based on these insights, Aakash designs a three-day festival with programming blocks that align with the preferences revealed in the data. He schedules acoustic sets for Thursday evening, reserves Saturday night for comedy headliners, and creates tiered pricing that respects the identified thresholds.

-

Personalized invitation: Because Priya opted to allow follow-up communications, she receives a personalized festival announcement highlighting the comedy and music acts that align with her past attendance patterns. The system even suggests specific performances based on her historical preferences.

-

Feedback loop: After the festival, Aakash sends a follow-up request through the Ticket Aggregator asking attendees if they're willing to share their festival experience data to improve future events. Priya can choose whether to share this new data point.

-

Ongoing control: Throughout this process, Priya can check her Ticket Aggregator app to see who has access to her data and for what purpose. She can revoke consent at any time, and the system will immediately cut off access to her information.

The path to decentralization

This is just one of the pathways. And this doesn’t address the specific problem Kunal Kamra raises — getting access to the data of his fans that BookMyShow currently stores. For that, creators like Kamra will have to reduce their dependence on centralized media.

It involves work. It’s far easier to build an audience on X or YouTube than to build your platform from the ground up. However, Venkatesh Hariharan, India Representative of Open Invention Network and a long-time contributor to the Open Source movement, points out that the ecosystem could evolve so that such work can be outsourced to say, a startup, which specialises in building platforms that are not dependent on X or YouTube. Kamra could then focus on creating content, and on performance, leaving other work to the specialists.

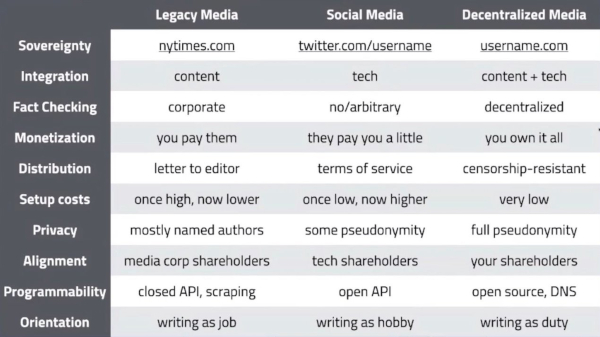

Many have argued for the need to move towards decentralised platforms. For example, Balaji Srinivasan, a tech entrepreneur and investor, has argued that decentralized media empowers individuals to control distribution and monetization, unlike legacy media's corporate constraints.

His argument is that traditional news outlets like newspapers control the content but charge readers, while social platforms like X are free but control what you can say through their rules. The next stage — decentralized media — would give people complete ownership of their content through personal websites and domains, without corporate gatekeeping.

(Source: Balaji Srinivasan’s presentation on decentralised media. The chart tracks how publishing has shifted from being controlled by companies to potentially being controlled by individual creators, with different trade-offs in cost, freedom, and responsibility at each stage.)

Venkatesh Hariharan says if such decentralisation happens, it would align with the original vision of the internet, which was supposed to empower individuals. “However, thanks to network effects and other drivers, power is concentrated in a few large corporations. Now the pendulum has started to swing in the other direction. There is a re-decentralisation movement today.”

In the early days of the internet, there was a promise about leveling the playing field so anyone could share ideas, innovate, and get noticed without first seeking permission from a tech behemoth. That ideal is what the web’s architects envisioned from the start. However, a handful of corporations turned that dream into a profitable business model, concentrating power in ways that now resemble the very gatekeepers the online world once sought to bypass.

Yet there is hope in the concept of “re-decentralization,” a term experts such as Hariharan are talking about and pinning hopes on. The idea is to restore genuine user control over data and online identity as opposed to leaving it in the hands of a few conglomerates. Hariharan cited the Beckn Protocol as a good example of decentralisation.

Let us consider something like India Stack: by providing open APIs for services ranging from payments to identity verification, it opens the door to new possibilities for smaller startups and innovators, not just the same Big Tech stalwarts. Still, it hasn’t solved the problem of centralization — for the power is still concentrated in the hands of the government.

The broader movement towards open experiments harks back to what the internet was meant to be: a malleable, shared platform that anyone can adapt to their needs.

Whether this will be enough to shift the internet’s balance of power back toward individuals is difficult to predict. While it is not legally tenable right now, this is where the moral arc of Kamra’s arc is bending towards. This is the moral arc that smaller artists such as the stand-up comedian we spoke to is holding on to.

This shift of balance isn’t impossible to imagine. Once upon a time, software was a creative domain that a bunch of creative people tinkered around in — until the behemoths led by Bill Gates and Microsoft took over. But as things are, the backend of the world practically runs on open source software such as Linux. And companies like Microsoft are collaborators in the ecosystem.

In much the same way, the internet has always carried a streak of rebellion, most visible whenever a new protocol or clever hack disrupts the status quo. And if the voices of the artists are anything to go by, Hariharan’s point is that today, that rebellious spirit seems to be waking up again, quietly but resolutely. The dream never really vanished; it just got overshadowed by ad models and closed-off digital ecosystems. If enough people insist on shaping the online world around personal autonomy and privacy, the vision of a truly decentralized internet may still stand a chance. And in the end, that could be how the early dreamers of the web prove themselves right after all.

Vishal Haria on Apr 12, 2025 12:50 a.m. said

"Consent request: Priya receives a notification on her AA app. The request clearly specifies what data ICICI Bank wants (transaction history for the last 6 months, investment details, etc.), why they need it (for loan eligibility assessment), and how long they'll keep it (say, 6 months)."

"Ongoing control: Priya can check her AA app anytime to see who has access to her data. If she changes her mind, she can revoke consent with a single tap, and the data access stops immediately."

The expiry or revocation of consent stops future data access. However, past data which was accessed, and stored (in this example by ICICI) may continue to be accessed forever. So, the burden remains on user (like Priya) to ensure requestor (like ICICI) will not act badly with the data.