[Image by ar130405 from Pixabay]

The scars still remain. Recently, there was a full-page advertisement of an Indian state touting its achievement in solar energy production. My octogenarian father scoffed at it since he is very circumspect of anything solar. And so are many Indians of his generation. This is so non-intuitive given that the sun is revered as a God in India, and solar energy is among the cleanest. I ask him is it the solar cooker effect of the 1950s? He nods and says it was one of the best con jobs that independent India has ever seen. And reminisces that the Prime Minister and all important technocrats of that era were talking about it. The solar cooker was also covered extensively in the print media of that era. He had tried to but could not see a working solar cooker. And as far as my father remembers, those who wanted to buy one could not do so easily.

I prod him on. As an Indian who has seen the proliferation of electricity grids, radio receivers, wireline telephones, pathology labs and X-ray machines, “dieselification” of the Indian Railways, automobiles, television, telephone booths (STD, or subscriber trunk dialling booths, as they are better known in India), internet, and mobile phones, he is sanguine that India has come a long way to make technology work for her citizens. He feels Indians aspiring for and choosing their everyday technologies without the government deciding for them or interfering is a good sign. He now laughs about taking care of the radio license and TV license booklets like his savings bank passbook!

While he is happy that technology is accessible to more Indians than ever before, he is also worried that the technology divide may be increasing. Indians of his generation who have witnessed all of India’s wars are intrinsically very aware of the importance of forex outflows. They are wary that India imports the core components of its consumer electronics that are now an integral part of the daily lives of Indians. Paradoxically, they also feel importing is better if we are forex comfortable since most grandiose indigenous technology development efforts in consumer technologies have invariably been “white elephants”.

Why is technology so important to Indians? The answer is obvious: just look around. Everyone is on their smartphones. About 375 million of us. You are probably reading this on your smartphone! Not only that, our social network is on the smartphone. More important, our political opinion is increasingly getting shaped by what we see on our smartphone. Yet, there is very little Indian about a smartphone other than the fact that we have adopted and adapted foreign technology to the Indian context. Indians are likely to import about $300 billion worth of consumer electronics in 2020, which is about three-fourths of total demand. Why does India have a negligible indigenous presence in electronics manufacturing? It is largely a result of government policies from the 1960s that has led us here.

Almost all of us connect to the internet using a smartphone. Mobile telephony in India is an interesting case study since it was among the earliest instance where the government offered licenses to private players to offer this technology-intensive service in India in the mid-1990s, thanks to the liberalisation. Private players were allowed to provide internet services in 1999. This was incredible since India had not opened its wireline telephone services to private players till then!

It is also interesting to note that the internet has its origins in a project started by DARPA—the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency of the US Department of Defense—and later transferred to the National Science Foundation, and finally to private telecom providers. Is there any Indian government-funded project that has had at least a fraction of world-wide impact like the internet? Or for that matter, will an Indian technology project ever make such an impact?

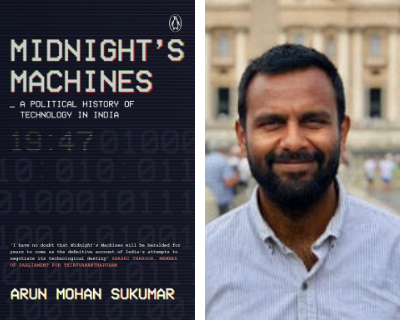

The answers lie in how the interplay of technology and politics evolve over time. It is useful to dip into history to understand how technology and politics have evolved in India, to understand the hits and misses. This ensures we do not commit the same mistakes. Midnight’s Machines, authored by Arun Mohan Sukumar, provides an analytical and scholarly study of the history of technology and politics in India. Arun has put together an impressive narrative of some of the important technology policy decisions and their impact on Indians in Midnight’s Machines. The standout feature of this book is that it intertwines technology and politics. It does not fall into the trap of presenting stand-alone histories of key actors, technologies, or institutions.

Midnight’s Machines is relevant for many of us who want to unravel the evolution of technology and politics in India. One gets a feeling that the scholar in Arun would have loved to expand on some of the theoretical constructs he introduces. However, he has done well to explain the theoretical constructs just enough for the reader to get a feel and in a language that a non-specialist can understand. Midnight’s Machines draws its strength from both Arun’s comprehensive research and storytelling. It presents the political history of technology in India in an engaging format.

The 1950s to the mid-1960s are covered in the section “The Age of Innocence”. The centrepiece of this section is the discussion on the solar cooker project. The failure of the solar cooker project is the story of how a newly independent India was let down by its politicians and technocrats in this project. It is a cautionary tale that is a must-read for all interested in technology policy. This section also covers how foreign aid helped India procure technology, including trucks, buses, dairy plants, etc. Foreign aid was also used to set up the IITs. Arun could have covered the contribution of the original group of IITs over the past 50 years from a technology-politics framework. And also analyse why our polity is motivated to set up more IITs in the past decade. Should India do things differently in terms of nurturing the new IITs?

The mid-1960s to the early 1980s are covered in the section “The Age of Doubt”. The hits and misses in the domain of electronics and computers is the heart of this section. Thanks to PC Mahalanobis and Homi Bhabha, India was quick to understand the importance of electronics and computers along with the Western countries in the 1950s. However, given the political priorities and India’s economic context, electronics and computers took a back seat. It was the wars of the 1960s that made India focus on electronics. Looking back, did India’s emphasis on self-reliance, especially in cutting-edge technology cost the country? Would India have started on the path of becoming a modern industrial society earlier if it was easier to import technology? There are no easy answers. The role of defining India’s technology future was concentrated in the hands of a few. Midnight’s Machines could have also discussed how in this era the best of our research talent were attracted to specialised research organisations and institutes like TIFR (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research), AEE (Atomic Energy Establishment that later became BARC, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre), CSIR (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research) labs, IITs, and IISc, rather than our universities. We are still living with the impact of this move that hollowed out good quality science and technology research in our universities.

The early 1980s to the end of the century are covered in the section “The Age of Struggle”. India’s nuclear programme, space programme and green revolution are covered in good detail. The sub-sections on “Appropriate Technology” and “Authoritarian Technology” remind us of our tumultuous past and how technology is framed in the political, socio-economic, and cultural contexts. Interestingly, these contexts are the ones powering the rise and rise of social media in India today. I think a discussion on the introduction of electronic voting machines in India would have been interesting. This is an indigenous digital technology used in a country which has a significant illiterate and digitally illiterate population. The story of how India’s polity and people accepted electronic voting machines would have been interesting reading.

The 21st century is covered in the section “The Age of Rediscovery”. The emphasis is on India’s ascent in IT services. Y2K receives pride of place. Missing are important aspects in the early part of the 21st century where package implementation, testing, infrastructure management, IT-enabled services, etc. became new service lines added to the traditional application development and maintenance. This was also the era Indian automotive and pharmaceutical industries came of age. The evolution of these two industry segments are not covered in detail. Indian bioscience and biotechnology came of age in the 21st century. A discussion on how this came to be, including the influence of the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) will be good to trace. In the section that summarises the role of technocrats, the reader is not clear why the exemplars list is limited to only M Visvesvaraya, Vikram Sarabhai, and Nandan Nilekani. For example, why is Homi Bhabha not included in the list? Especially since Bhabha seems to have fulfilled the three criteria of having an unyielding belief in technology to solve economic and social problems, occupied a formal role in the government, and commanded respect from colleagues. He was among those who championed big R&D mission-mode projects in India starting with the AEE—the model later followed by ISRO. He also understood the importance of emerging sciences like bioscience and technology like computers for India.

A section on the increasing influence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in India and its link to politics and citizens would have been useful for readers to decipher the context playing out in India today. While it is still early days for fairness, accountability and trust in ML in India, these will have far more impact on India given the nature of our digital divide. While on one hand globalisation in terms of trade in physical goods seems to be in choppy waters, on the other hand a few global social media platforms seem to be going from strength to strength.

Given the increasing importance of technology in the geopolitical landscape in the 21st century, and India’s aspirations for herself and the world, it is imperative to understand the evolution of technology in the Indian political context. Midnight’s Machines is a definitive book in this domain. Faculty in business schools who teach courses on the Indian macro environment should consider including sections from Midnight’s Machines as part of their reading. This is a must to sensitise future corporate leaders to the important interplay between technology, politics, and globalisation.

India’s current minister for external affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar succinctly encapsulated the emerging global geopolitical landscape in his speech at Carnegie India’s Global Technology Summit 2017 when he was India’s secretary of external affairs. This is the best description of today’s context that makes Midnight’s Machines a must read. “The history of international affairs is in many ways the history of technology. Equations between societies and nations have been largely determined by this factor. Most dramatically, they were expressed in the outcomes of military conflicts...But there is also the more secular rise of economic power, one that was essentially driven by the growth of technological and later industrial capabilities. If technology impacted the international power distribution, the pace and capacity for adaptation certainly contributed to the rise and fall of nations—and eventually, to the nature of the global order itself. The current era has, of course, introduced many more imponderables with the proliferation of technologies. There are two broad propositions that are relevant for consideration today:

- The bandwidth of technologies that can make a difference is steadily widening, going well beyond those with narrow and direct military application.

- Influence and power are derivatives not just of knowledge but of its successful application. This implies access to technology, its absorption and larger percolation, and most important, its effective deployment.”

PS. I missed an index in Midnight’s Machines. An index is essential since this book is likely to become reading material in graduate and doctoral-level courses in India and elsewhere. Hopefully, subsequent editions will have one.

(Views expressed are personal.)

Also Read

The cooker affair: A cautionary tale of using science for political ends: An extract from the book 'Midnight's Machines' by Arun Mohan Sukumar