[Image from Harper Business India/Twitter]

The Tata Administrative Service (TAS) was created in 1956 by JRD Tata, the visionary chairman of the Tata group (1938-90), to develop leaders for Tata companies. Tata’s Leadership Experiment: The Story of the Tata Administrative Service, is an engaging history of the TAS since its inception, written by three TAS alumni, Bharat Wakhlu, Mukund Rajan, and Sonu Bhasin (published by Harper Business in August 2022).

The history of the TAS is interwoven with the evolution of the Tata group through two eras: the so-called “socialist” era of the Indian economy until 1991, and the more “liberal capitalist” era since then. It also spans the terms of two leaders of the group: JRD Tata until 1990, and his successor Ratan Tata from 1990 to 2012. The Tata group has evolved from being an iconic values-based Indian business conglomerate, hardly known outside India, to becoming a global enterprise with a large international footprint under Ratan Tata’s leadership.

My career with the TAS spanned from 1965 to 1989, all in the JRD era. The three authors’ careers in the TAS overlap with the Ratan Tata era. Bharat joined in 1985; Sonu in 1987; and Mukund in 1995. Bharat was in-charge of Tata Inc. in the US when the group was acquiring and integrating foreign companies as it expanded its international footprint. Mukund was executive assistant to Ratan Tata for 12 years. He was elevated by Ratan’s chosen successor, Cyrus Mistry, to the apex council he created, with responsibilities for brand management and ethics in the group. When Ratan Tata removed Cyrus in an acrimonious dispute, Mukund had a ring-side view.

The book is written well. It weaves the personal stories and views of dozens of former TAS officers with the authors’ own reflections. Its’ insights about the impact of Ratan Tata’s personality and management style on the group’s governance are revealing. More important though, to my mind, are some broader questions the book raises about prevalent concepts of good corporate governance.

Corporate governance in the 20th century

Concepts of corporate governance which spread from US schools of economics and business management across the world in the later part of the 20th century, which the Tata group was also influenced by as it expanded its global footprint, have caused harm to the welfare of human beings and the natural environment.

For one, the business of business can no longer be just business. Societal values must guide corporate governance, not stock market valuations. Corporations must listen to, and account to, all stakeholders, not just shareholders. This remains the Tata way, the authors say hopefully, even though stock-markets compare the performance of Tata companies with others based on their financial valuations to sort out which corporations are ‘value creating’ and which are ‘value destroying’. Corporate responsibility for the well-being of the environment and society does not figure in the market’s evaluation.

Another idea, associated with financial value creation, is that business conglomerates destroy value, and they should be broken apart. The Tata group is perhaps the most complex business conglomerate in the world. It is composed of pioneering Indian enterprises in many industries, ranging from steel and basic chemicals, to manufacturing enterprises that design and make complex engineered products such as motor vehicles and watches, to the country’s oldest and largest IT services company—Tata Consultancy Services. JN Tata, the group’s founder, also started a world-class hotel chain, the Taj group, a century ago, with the iconic Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai. JRD Tata created India’s first international airline, Air India, soon after India’s independence. It became an international benchmark in the service industry. (Air India was nationalised in the “socialist” era, and finally returned to the Tata family this year.)

Governing a business conglomerate

When the legal purpose of a business corporation is limited to the production of returns only for its shareholders, it becomes the legal responsibility of the board and CEO to produce results for them. This creates special problems for governance of conglomerates.

A principle of good corporate governance is that the preferences of any single shareholder of the company, even the promoter (as Tata Sons is for Tata companies), should not interfere with the decisions of the company’s board, which must be even-handed for all shareholders. The virtue of what any investor, including the promoter of the company, does with what it earns from the company, does not give it any additional legal right to interfere with the board’s decisions. Therefore, the fact that two-thirds of Tata Sons’ shares are owned by charitable trusts, does not give Tata Sons/Tata Trusts any superior rights over other shareholders of Tata companies.

The authors say that the societal worth of a company must not be judged by the amount it spends on “CSR”. Some percent of profits may be dedicated to building hospitals or schools, or other social welfare measures. This could be via philanthropies or even direct spending (such as the mandated 2% of profits under Indian law). However, this cannot be compensation for the harmful impacts of the company’s conduct, its products, and its operations on society and the environment while producing its financial surpluses. Therefore, genuinely responsible business leaders must find other ways, not just philanthropy, CSR, and the activities of charitable trusts, for making the world better for everyone.

Development of values-driven business leaders

The TAS was an institution intended for this purpose by JRD Tata. The authors discuss the limitations of the TAS, which arise from the legal limitations on the role the centre of a diversified conglomerate can play within its companies. A group HR function cannot direct the postings of TAS officers within companies and their rotation for their career advancement.

The authors have interviewed many TAS alumni of different vintages: a few from the JRD Tata era, and many from the later era. They point to a shift in the objectives of the TAS itself from the 1980s. The TAS expanded greatly to recruit more vigorously from management schools around that time, and in larger numbers too, to provide modern managers for Tata companies, especially the smaller companies that did not have the requisite scale for their own leadership development programmes. Along with the professionalisation of management, came “professional” concepts of HR management, with systematic support for their career development until they rise to top positions, which recruits in the TAS began to expect. Hindustan Unilever’s professional management development was often cited as the benchmark in India.

A fundamental difference should be noted between the TAS and programmes like HUL’s. HUL is a single corporate entity whose board can set the rules for the entire company. Therefore, HUL’s central HR function can track, train, and move personnel across HUL. Whereas a central HR function for the Tata group cannot direct the careers of TAS officers after they have been placed within Tata companies.

The second difference between the TAS and professional management development programmes like HUL’s is in their concepts of leadership. JRD Tata chose to call his service the Tata ‘Administrative’ Service, rather than the Tata ‘Management’ Service. Its name followed the Indian Administrative Service, which attracted the best Indian talents in the early years of India’s independence who were attracted to the call for “nation building” (as I must admit I was).

JRD used to say that whenever he had to take a difficult decision about whether India or the Tata group would benefit more, he would decide in favour of India. He observed that such decisions benefitted the Tata group also. His mind worked the same way while conceiving the sort of leaders the TAS would groom. However, as the TAS expanded, its orientation seemed to change towards becoming a professional management service competing with the likes of HUL.

How NOT to govern a business conglomerate

GE is the iconic US industrial conglomerate. Founded in 1892, it is almost as old as the Tata group which was founded in 1868. GE companies produce electrical equipment, home appliances, industrial goods (power and transportation equipment), as well as high tech aero engines. By mid-20th century, it employed 400,000 persons in the US. In 1981, Jack Welch was selected as CEO of GE, succeeding the genteel Reginald Jones.

Welch led the campaign in US markets to promote the idea that creation of shareholder wealth is the purpose of business. Welch was a hard-driving manager by the numbers. He bought and sold companies to create value for GE’s shareholders. Financial engineering, rather than product engineering, was Welch’s way for generating wealth. In his management framework, people were numbers, and were to be managed by the numbers. Known as “neutron Jack”, he stripped companies of their employees to increase their profits. The bottom 10% of employees, ranked by their objectively measured performance, were stripped out every year to improve the productivity of GE’s employee pool.

During the 20 years Welch was at its helm, the market value of GE increased from $14 billion to a whopping $600 billion. Fortune magazine declared Welch “The Manager of the Century”.

GE was famous for its professional leadership development and HR processes. “When a company needs a CEO,” said Fortune, “it goes to General Electric, which mints business leaders the way West Point mints generals.” GE alumni would go on to lead many large US corporations—Boeing, Home Depot, Chrysler, etc. Signs of trouble in GE were already visible when Welch retired as a very wealthy man. Welch’s chosen successor at GE, Jeffery Immelt, carried on Welch’s way to fix the conglomerate. The results were disastrous. GE was dropped from the Dow Jones industrial average. “Once a paragon of modern management excellence, GE became a punchline,” says David Gelles, the author of The Man who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America—and How to Undo His Legacy.

Neither can the Indian Administrative Service, which had inspired JRD Tata’s vision of the TAS, provide it a suitable model. While IAS officers serve in India’s states as well as Centre, the IAS is a centrally managed service created by India’s Constitution. Therefore, the Central government is mandated to manage the careers of all IAS officers, which, as mentioned before, the Tata group’s centre cannot do for TAS officers.

Which way in future?

The IAS is sometimes described as India’s “iron frame”, like the British managed Indian Civil Service was from which it has evolved. However, the officers of the IAS were expected to become catalysts of development in the country, in its states and districts, rather than as managers of law and order and collectors of revenue, as the ICS officers were. IAS officers must serve the people, rather than merely implement the plans of their masters at the Centre.

Following years of criticism of the IAS, the Indian government is devising measures to reform it. Two philosophies are clashing in these reforms. One is to make IAS officers more efficient managers of public resources. Therefore, best practices from corporate HR management are being applied—lateral entry, domain expertise, up or out, etc. The other is to re-orient IAS officers to become catalysts of systemic changes in the country, with greater emphasis on equity rather than efficiency.

More efficiency in the use of resources to produce measurable outcomes is the objective of good management taught in management schools and applied by business consultants. Whereas systemic change that creates more equity in society is the objective of public leadership.

Looming global problems listed in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals require leaders in all sectors to adopt more systemic approaches. Business leaders too must reorient their ways to make the world fair for everyone. They must be fair to their employees within: therefore, compensation systems must change. CEO salaries, which have increased to over 200 to 300 times median employees’ salaries (from 20 times or less as they were 30 years ago), must be brought down to earth. TAS officers complained to the authors of Tata’s Leadership Experiment that TAS salaries have not kept up with the market. However, rather than following the herd and increasing TAS salaries to match, perhaps the TAS should be leaders of change in the other direction.

Governance of business entities must change to make them legally accountable to all their stakeholders, not only their shareholders. The measure of great business leadership must be the improvement of the lives of the poorest people in society rather than the wealth of people on top.

JRD Tata had a talisman: Do what is good for the country. Gandhi also provided a talisman to all leaders in government, business, and society—the principle of anantodaya. Whenever you make a policy or plan for your institution, think of how it will benefit the life of the poorest person you can think of, he urged.

Officers of the TAS, and IAS too, must learn to lead in a new way. Not the management ways taught in business schools, nor the ways of corporations with the largest market caps. But the ways of “servant leadership” Gandhi had demonstrated. Learn with the people. And be a catalyst of change in their lives.

Still curious?

- Read an extract from the book Tata’s Leadership Experiment

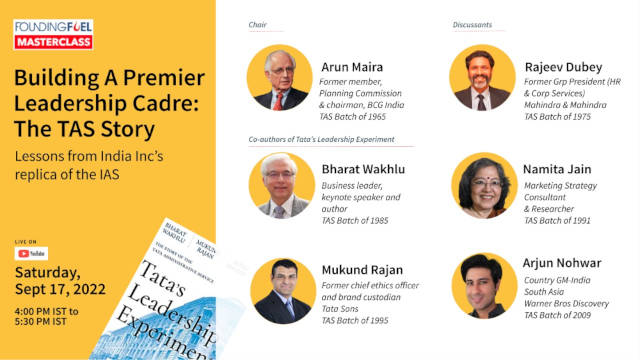

- Join us on September 17 for a Masterclass