For many years, certainly till around the mid-1990s, the TAS succeeded in consistently attracting outstanding talent. The brightest students from the best educational institutes vied to get into the TAS. The selection of these individuals took place, for the most part, in an era when India was still a protected economy, attractive job opportunities were relatively limited, and the TAS itself was hiring very few officers, typically in single digits each year. Many of those selected during this period […] would make a mark in the Group, while a number of others, like T.K. Balaji, Kris Ramachandran, Siddharth Kak, Navtej Sarna, Vir Chopra, Raghuram Rajan, Patu Keswani and Srikumar Misra would leave to go on to build highly respected careers in the corporate world or as entrepreneurs, as well as in other realms such as public policy, the arts and culture.

As the Indian market opened up in the post-liberalization era, however, a variety of exciting new opportunities became available to India’s best and brightest. The TAS had […] traditionally been behind the curve on offering market standard compensation. The effects of this became visible as it began to struggle to attract the best students from B-School campuses. Instead of the TAS, many of the brightest students increasingly opted for lucrative careers in international banks and management consultancies. Modest TAS salaries aside, these students could spot only a few senior TAS officers leading large companies. By the late 1990s, the TAS had been in existence for just under fifty years; but it could not showcase a large bench of Managing Directors and CEOs who had started their careers as TAS officers. In contrast, the international banks and management consultancies, and indeed, many multinational companies, offered clear and well-defined career paths for their management cadres.

[…]

Many TAS alumni today regret that the Group made few efforts to invest in their growth and development after they had been selected. And while there is something to be said for the expectation that the officers would be self-starters and take the initiative to find learning opportunities on their own, the fact is that even modest-sized multinational enterprises have far superior training programmes for their managers, as compared to anything the TAS ever put together.

In a world where there is growing sophistication of skills in every functional domain, even general management skills that TAS officers are expected to have need to be honed and sharpened continuously with formal inputs. Gone are the days when well-meaning young managers like Xerxes Desai, armed only with degrees in subjects like history, politics and philosophy, could flourish simply because of their intuition and people management skills. In the changed business world, especially after 1991, specialization or knowledge of a particular domain has become almost de rigueur for any leader. Alongside a waning commitment at the very top to nurture and grow these skills in TAS officers, it is increasingly the case that leaders across Tata companies are being hired laterally for their perceived domain skills and managerial capabilities rather than groomed internally.

Be it a Sunil D’Souza from Whirlpool who replaced Ajoy Misra (TAS 1980) as the Managing Director of Tata Consumer Products, a Sanjay Dutt from Ascendas who replaced Brotin Banerjee (TAS 1998) as the Managing Director of Tata Housing Development Company, or the induction of Saurabh Agarwal, formerly from the Aditya Birla Group, as the Group CFO, lateral hires seem to be getting preferred for many top-level vacancies in the Tata Group now. As a proportion, far fewer active senior leaders across the Group today have emerged from the ranks of the TAS than ever used to be the case in the past.

In trying to assess the achievements of the TAS thus far, then, let us evaluate delivery against expectations. TAS officers were to be selected in significant measure for their ethics and values orientation. We have seen in this book that there were indeed some aberrations through the decades—not all TAS officers were paragons of virtue, unfortunately. There are a few hairy stories TAS alumni still whisper about, including the alignment of a few TAS officers with the nefarious activities of some Tata satraps that went far beyond the call of duty. But it is also true that the vast majority of TAS officers seem to have been untainted by familiar Indian allegations of corruption. Broadly speaking, many TAS officers did justifiably earn respect for their integrity and the positive examples they set for others both within their companies and outside.

The TAS, at its inception, took a lead in the Indian corporate world by actively recruiting women in the cadre. Khorshed Jhaveri, the first woman TAS officer, was recruited in 1958 when women in management were quite the exception. For the next ten years, women continued to be part of the new batches. One of those early recruits, Camellia Panjabi, in fact went on to earn accolades, not only in the Tata Group, but as an internationally respected restaurateur and hospitality industry veteran. And then, inexplicably, the TAS stopped recruiting women. It even stopped accepting applications from women from the late 1960s onwards. This changed only in 1982 when three women were recruited, among them Vibha Paul Rishi, who played a role in the creation of Titan, and went on to a successful career in the multinational, Pepsi.

The fact that a number of women TAS officers are known more for their work outside the Group tells a story in itself. While attrition has been a problem within the cadre as a whole, it is the attrition among the women TAS officers that is startling.

[…]

Another important yardstick for evaluating the success of the TAS would be the achievements of the cadre in championing the unity of the Tata Group. Here, it has to be said that while the idea of a strong and cohesive Tata was one that appealed to most TAS officers, too few of them were actually able to play any meaningful role in delivering on this concept. Many TAS officers tended to build senior careers within single Tata companies and had little role to play in shaping the fortunes of the conglomerate, especially during the years when it dramatically expanded under Ratan Tata’s stewardship.

Very few TAS officers enjoyed the access or were able to command the clout to influence the Group Centre. A far greater role in preserving the Group’s unity was played by two personalities who occupied the position of Tata Group Chairman, first JRD Tata, and then his successor, Ratan Tata.

A third measure of success could be how many TAS officers were able to distinguish themselves in any significant manner for their business genius or their entrepreneurial flair. Many have certainly been admired managers and played important, sometimes vital, roles in the growth of a number of Tata businesses; several continue to do so today. However, […] during the post-liberalization years when the first crop of TAS officers came into their own as Heads of companies, and younger hires began to make their mark, relatively few created a long-lasting positive impact.

These few would include Xerxes Desai (TAS 1961), who created Titan as one of India’s best-known brands. […] Several potential future leaders of the Group were unfortunately lost due to the significant number of exits of senior TAS officers from companies like Tata Motors and Indian Hotels in the wake of the change of guard at the top, when Ratan Tata displaced the satraps.

[…]

Across large Tata businesses, managers from outside the TAS, such as Dr Jamshed Irani at Tata Steel, S. Ramadorai at TCS, Prasad Menon at Tata Chemicals and Tata Power, and Ravi Kant at Tata Motors, would enjoy significantly more influence in shaping the fortunes of these companies. Very few TAS officers would ever come to rub shoulders with the Chairman of Tata Sons.

(This extract, from the book Tata's Leadership Experiment: The Story of the Tata Administrative Service, by Mukund Rajan, Sonu Bhasin, and Bharat Wakhlu, is reproduced with permission from Harper Business.)

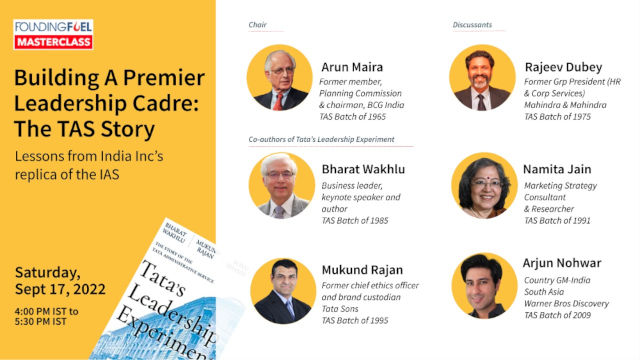

Join us on September 17