After years in obscurity, Sridhar Vembu, an IIT-Madras and Princeton-trained engineer who started Zoho, a tech company, 26 years ago, regularly finds himself at the centre of attention.

The interest is partly because of Sridhar’s personality. When he returned to India from the Silicon Valley in 2019, he didn’t settle down in Chennai, the headquarters of Zoho, but in a village called Mathalamparai, 650 kilometres away in Tenkasi district in Tamil Nadu.

The very idea of a billionaire moving to a village that's hardly known and hard to pronounce, and images of him pedalling a bicycle around paddy fields, driving an electric auto, or relaxing in a thinnai (shaded verandah) wearing a half-sleeved shirt and a white dhoti evoked curiosity.

But none of it would have mattered if it weren’t for the fact that Software as a Service (SaaS) is now coming of age. Global management consulting firm Bain & Co says it will produce India’s next wave of tech giants. Zinnov, a tech-focused research and consulting firm, says the Indian SaaS industry is set to cross $100 billion in revenues by 2026.

Cut to 2008. Sharad Sharma, co-founder at iSpirt, a think tank focused on promoting product startups, recalls when Sridhar was invited to speak at an industry conference at the Le Meridian hotel in Delhi. Sridhar, who had placed his bets on the cloud four years earlier, was absolutely insistent that cloud computing as the new platform for building applications was coming and it was going to be transformational. However, there was significant scepticism in the room.

Today, as a leader of the pack, all eyes are on Vembu and whether he will be able to out-innovate the rest and keep Zoho ahead of the game.

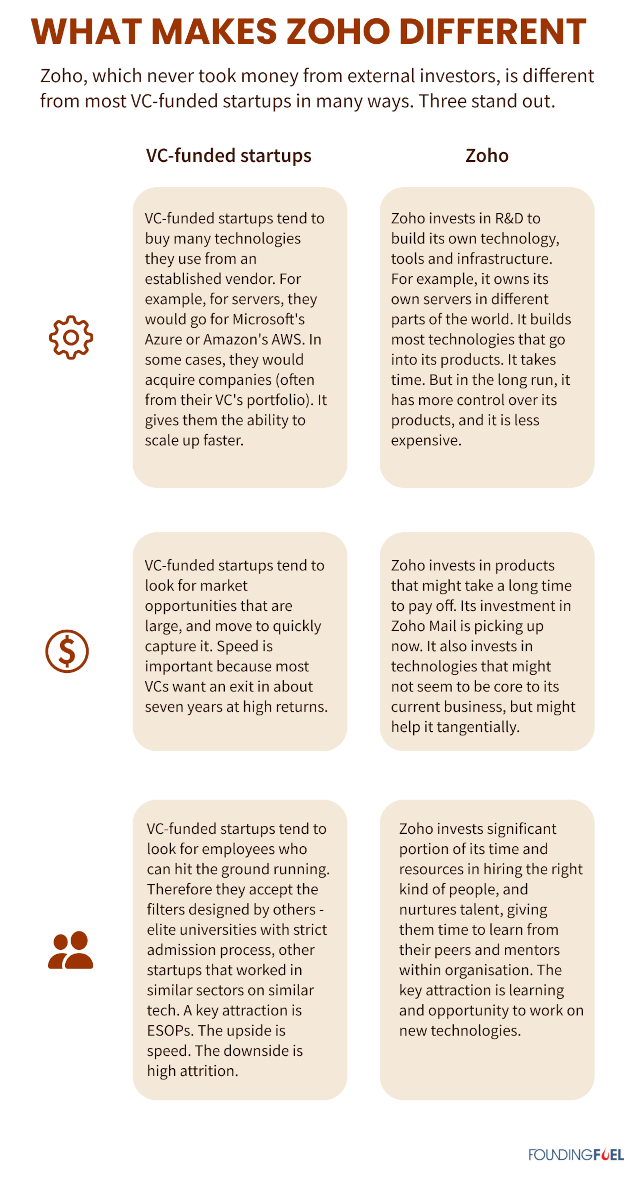

Sridhar’s journey so far has some hints on what the road ahead might look like. He built Zoho by questioning the conventional narratives—focusing on software products when IT service was the rage; refusing VC money, despite being in the Silicon Valley; building a culture of autonomy and trust, rather than on metrics when companies were swearing by measure and manage; hiring people ignored by the mainstream; investing heavily in building his own technology infrastructure, even if it took time, when many opted to rent from established companies or acquire emerging ones; by going through the grind of putting culture first, and aligning strategy and execution with that, instead of sweeping culture under the carpet of “scaling up”, as if it’s an irritant; by taking time to think of second order consequences of the decisions, when everyone was optimising for first order results.

Sridhar continues to take the path less travelled. While many business leaders are breaking their heads over bringing employees back to the office or moving to a hybrid model, he is experimenting with new models of work, setting up rural offices doing high-end technology work and connecting them to hubs in small cities and towns. He is laying the ground for the long-term success of the company—investing in building tools and infrastructure and strengthening its unique culture.

Yet, ironically, it was Zoho’s fiercely autonomous culture that spawned at least 133 entrepreneurs who have set up SaaS startups, many of which are giving it a run for its money. The most prominent among them is Girish Mathrubootham, who founded Freshworks and listed it on Nasdaq last year. Freshworks is quite the poster boy for SaaS unicorns. And is the only one of its kind till date. Unlike Zoho which has been bootstrapped from the very start, Freshdesk relied on venture capital for its growth, possibly the reason why the Bain report tends to focus more on the activity among VC-fuelled SaaS startups.

Today, Sridhar is also investing in R&D ventures—focused on semiconductor chips, robotics, high-speed optical scanners and MRI machines—guided by a larger vision for the company. Amidst all this, he spends time in a village school he set up, which could become a model for community engagement, the way its training programme, Zoho Schools (nee Zoho University), has over the years. That’s not all. Sridhar is also working on creating a new programming language, called Pali.

All of this puts Zoho on a path to becoming an iconic institution, much like what FC Kohli was able to achieve at TCS starting out in 1969. And Sridhar knows it.

His big ideas and principles, however, are overshadowed by his combative public persona. Established Indian entrepreneurs are not known to speak their mind in public. Not Sridhar. In interviews, panel discussions and on social media, he leaves no one guessing what he thinks about business leaders such as Jack Welch (because he focused on financialisation, and destroyed a solid engineering, R&D-focused company), economists such as Paul Krugman and Raghuram Rajan (because they push for liberalisation of imports, when India should be building strong manufacturing capability), and management gurus such as Clayton Christensen (his theory of disruptive innovation predicted that iPhone will fail) and CK Prahalad (Indian IT services companies missed building cloud infrastructure opportunity because they thought it was not their core competency while Amazon built AWS), and institutions such as Harvard Business School (because reductionism underpin their theories/ideologies)

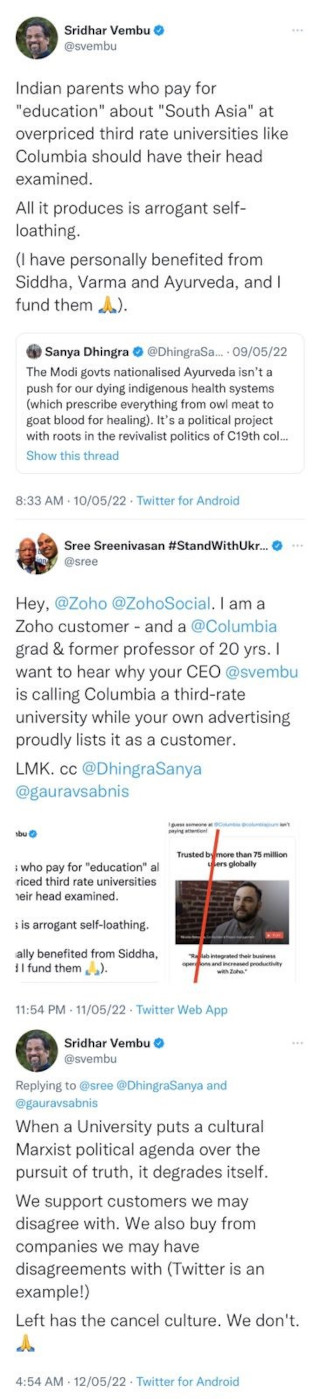

Earlier this year, he termed a post on Covid-19 treatments by a McGill epidemiology professor as ‘dogmatic’ (because their prescriptions don’t reflect the “genuine disagreement there is among highly credentialed doctors and medical professors”), and more recently, referred to Columbia University, a global client Zoho serves, as a “third rate” university. His posts on Twitter, mostly posted in the mornings, question popular narratives. This in turn has led to intense debates on Twitter with responses, ranging from bigotted trolling to thoughtful counterarguments.

In 2020, he accepted an invitation to speak at an RSS event. It led to calls for boycotting Zoho products. Last month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi mentioned Sridhar Vembu and the work Zoho is doing in Mann Ki Baat. Mohandas Pai, former CFO of Infosys, and a prominent voice of the right, used that as a cue to write a column arguing that the Modi government should make him a cabinet minister in charge of rural development.

All this comes at a time when Zoho is facing a pivotal moment in its journey. To get a sense of its way forward, we have to understand Sridhar’s own journey. For, his ideas and worldview—rooted in his extensive reading and personal experiences—are much more intertwined with Zoho than what’s visible on the surface.

The turning point

In 1999, at the height of the dotcom boom in the US, Sridhar faced a question that would determine the path that Zoho would take in the future.

A technology company offered to acquire Zoho, then called Adventnet, for $25 million. At that time, Zoho was three years old, didn’t have much revenues to speak of, had fewer than 100 employees, all based in Chennai, and was still focused on surviving or as Sridhar likes to say, “putting food on the table”. They were frugal, attended tech fairs travelling long distances by car, and staying in cheap motels. They sometimes took up contract work from companies to pay bills. Sridhar’s wife, Pramila Srinivasan, a PhD in electrical and computer engineering from Purdue, supported the household with her income.

“If we don’t sell this now, and if we screw it up, and it all comes to zero in five years, and we are dead, will we have any regrets?”

When the offer was made, he went to his co-founders—Tony Thomas and his friend Srinivas Kanumuru, Sridhar’s brothers Kumar Vembu and Sekar Vembu, and Sekar’s classmate Shailesh Kumar Davey—for their views. He didn’t paint a picture of what could go right if they stuck on with their company, he didn’t point to a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Instead, he asked, “If we don’t sell this now, and if we screw it up, and it all comes to zero in five years, and we are dead, will we have any regrets?”

The question is also interesting because even back then Zoho was not a typical startup.

His co-founders were unanimous and clear. There will be no regrets. They were not in it for money, but to build something substantial.

Vijay Sundaram, who was a classmate of Thomas at St Joseph’s school in Bangalore, knew Sridhar from the early days. In 2014, he joined Zoho as its chief strategy officer. But even back in the 90s, Sridhar had “an enormous amount of self-belief, not just in himself, but also in the organisation, that they will be world-beaters.”

“Very few people have that,” he said. “When you have that self-belief, you do things for the long term.”

Armed with that self-belief, Sridhar continued to sell its two products—SNMP API and WebNMS—to global customers. He was also learning how competitive dynamics play out. For example, its first major customers, Japanese printer makers such as Kyocera and Konica Minolta preferred buying the software from him rather than from HP, because it was a competitor. To find market opportunities, you have to look at the larger system.

As his business grew from a few hundred thousand to ten million dollars, Sridhar also noticed what was happening in the market. There were 300 networking companies at that time, about half of which were his customers. The first signs of the end of the dotcom/telecom bubble were showing up on them. He realised that it would eventually show up in Zoho too. Then September 11 happened, the bubble burst, and with that most of their customers shut down, draining its revenues.

Zoho didn’t go down in the crash, partly because its Japanese customers were doing well, and the Chinese had started investing in telecom. It’s also because, through the boom time, Zoho remained frugal and didn’t go on a hiring spree. They survived, and revenues came back to the $10-12 million range.

However, that market was limited. Unlike the startups that measure the market opportunity by metrics such as TAM (total addressable market), which pushes analysis towards irrational optimism by not accounting for the money that could be flowing in from generous VCs or from well-funded companies taking a hit to capture markets, Sridhar prefers to go OPAM. In other words, organically, profitably addressable market. The market that SMPS-API and WebNMS catered to offered stability, but not growth. A stable market, for ambitious businessmen, is also a stagnant market.

During the first few years, Sridhar, Tony, Sreenivas, Kumar, Sekhar and Davey were equals in terms of decision making. By 2000, Sridhar had assumed the role of CEO, and during the crash, had firmed up plans on how to take the company forward. But there was no consensus. For example, Kumar wanted to go full hog on the Indian market. Sridhar wanted to do global markets first.

Between 2002 and 2004, the founding team separated. Kumar would go on to found GoFrugal, a retail ERP company. Similarly, Sekar, Tony and Sreenivas would go on to start-up Vembu Technologies (a backup and disaster recovery software firm), edcite (education) and vTiger (customer relationship management). Sridhar has two more siblings, a sister, Radha Vembu and Manikandan Vembu (Mani), both of whom work in Zoho.

VCs “tend to impose premature ambition on entrepreneurs and demand premature execution”

Sridhar and Davey stayed on to take the company to the next phase. They had a great team put together by Kumar and Sekar in Chennai. They had capital, and WebMNS was bringing in revenues. They didn’t have to depend on VCs, who Sridhar says, “tend to impose premature ambition on entrepreneurs and demand premature execution”.

Now, Sridhar had the freedom to allocate capital at his own pace, and shape Zoho in his own image. The first step was to invest in new lines of business. “With WebNMS, we were supplying to OEMs and one step away from the end-users. With the new businesses we went closer,” Davey said. The first was ManageEngine, IT management software aimed at small to mid-sized businesses, which started yielding results in a year. The second was Zoho.com, which provided applications on the cloud. It started with an Office suite (only to find Google entering the space by acquiring Writely and other products). Then it launched a CRM product, that would bring it face to face with Salesforce.com. “We figured it would be easier to take on Salesforce, than Google,” Sridhar later joked. Salesforce would eventually offer to buy them out, but Sridhar had made the decision—to remain independent—already in 1999.

What distinguishes Zoho, however, is not its ability to figure out OPAM and choose which markets to fight for. It is its tendency to reinvest its profits in technology that would yield results over time.

This is in sharp contrast to the “move fast and break things” model that dominates the world of startups today.

This and many of Sridhar’s other ideas started germinating in his early years.

The moorings

A few years before he was born, Sridhar’s parents had moved to Chennai, and he did his schooling there. During summer vacation and other long holidays, the entire family went to their ancestral village in Thanjavur district in Tamil Nadu. When you are in that region you literally walk in the shadow of history, bumping into ancient temples every few kilometres. One such temple is in Gangaikonda Cholapuram, about 15 km from his village. The contrast between the temple’s grandeur—its main tower is 55 metres tall—and the poverty all around would strike him hard. And, he would ask himself, how could a system that built such a structure a thousand years ago, lose all that? He tried to find answers by studying history and economics.

Japan made a strong impression on him, Davey said. (Davey himself grew up in Thanjavur (the town), home to an even grander temple.) Sridhar studied the history of Japanese companies closely and was particularly impressed by the model of investing in high technology as a matter of conviction.

In Driving Honda, one of Sridhar’s favourite books, Jeffrey Rothfeder writes, “Honda’s emphasis on R&D is a distinctive characteristic of the company, a competitive edge in Soichiro [Honda]’s view… ‘We do not make something because the demand, the market, is there,’ he said. ‘With our technology we can create demand. We can create the market.’”

If Zoho’s medium-term strategy was about figuring out the OPAM, its long-term strategy was to build infrastructure. It’s in strong contrast to the IT Services sector, where the top companies grew by finding more domains and more geographic locations to apply their core innovation—the global delivery model—rather than investing in technology infrastructure, for example, cloud services, on which Amazon took a big bet. Zoho builds its own servers instead of renting it from Amazon’s AWS or Microsoft’s Azure.

“A lot of companies will build on an AWS or Azure,” Sridhar said. “They already have a lot of capabilities and they will build on them and launch a product. The flip side is that you are spending a lot of money on those platforms. They are not cheap. If you read the filings of public companies, 20% - 22% of revenues go into those bills. And then another similar, bigger bill for marketing. That is one of the reasons why a lot of startups have trouble making money. They move too fast, and so they have not thought through the cost implications of what they’re doing.”

(The same logic applies to acquisitions. Most of them fail because of incompatibility of tech (not to mention culture), but more importantly, the organisations lose out on the tribal knowledge that came with actually building the product. When Salesforce acquired Slack recently, Vembu half-joked with his team saying it was good for Cliq, Zoho’s alternative to Slack.)

“With external money, you can get to the market fast, but you are also on the treadmill”

“We don’t have outside money to spend,” Sridhar went on. “Our approach optimises the fact that we have to have some business model profitability before we go into this. That means that if you have reliance on a costly external technology, that may not be viable for us. We’ll be spending more than we make. And we cannot afford to do that for very long. It is a choice forced on us by the model of staying private. With external money, you can get to the market fast, but you are also on the treadmill. Fast growth is mandatory. You cannot say, let me grow slower. You don’t have that option. That freedom is why we are private too. It imposes a cost, which we are happy to pay.”

Sridhar is happy to pay that cost because benefits eventually accrue. Because you own it, your margins are high. And still, you can offer your product to your customers at a lower cost. A good product that’s well priced attracts customers better than expensive marketing campaigns. Sometimes, it might take longer, and you have to stick on the strength of your conviction. Zoho launched its mail product around the time Google launched Gmail. Today, it is one of its fastest-growing, driven by customers, especially in European countries such as Germany, looking for privacy and security. One of the ads for Mail reads, “Your inbox is not a Billboard”, taking a swipe at Google.

This kind of patience is another dimension of the lesson Zoho learnt during the bootstrapping years—be frugal. Frugality is about delaying gratification—or realising that one doesn’t need to go all the way to gratify cravings. When a businessman told Sridhar he doesn’t have the kind of R&D budget Zoho does, Sridhar responded by asking how much he had spent on building his house and the price of his Mercedes Benz. The house cost about Rs 60 crore. “You could have built a good one at Rs 6 crore. There, you had the budget,” Sridhar told him.

This episode also highlights why it’s not just about money, it’s about mindset, about culture.

Culture eats strategy for lunch

After Vijay Sundaram, presently Zoho’s chief strategy officer, decided to join the company in 2014, he had several long conversations with Sridhar. In these conversations, Sridhar would talk about the company and his vision. But Sundaram still had no clarity on his own role. Whenever he brought that up, Sridhar discouraged him from going in that direction. “Just spend some time there, you will figure it out yourself,” Sridhar said.

“There is a joke in Zoho that we never came out of the startup mode,” Davey said. Most top managers have been around since the early days, have a clear understanding of what their respective strengths are and what needs to be done, and gravitated towards those roles. It also reflects the high degree of autonomy in the organisation.

On the engineers’ work table, it translated to learning by doing, a high tolerance for mistakes—and the bedrock on which they stand—trust.

Mani, Sridhar’s youngest brother, joined Zoho as an engineer in 1998 and was trained by Kumar. He is now the COO. (“I am the only one who didn’t go to IIT, or scored above 80% in school,” Mani said during our conversation. “Zoho’s best-kept secret”, Ambi Moorthy, a SaaS entrepreneur, tweeted recently.)

“We had to learn everything. And we believed without doing we cannot learn. So, whether we do it right or not, we have to do it”

Mani said this culture grew out of its focus on building software products. When Zoho started, people were looking up to companies like Infosys (which was founded in 1981 and listed in 1993 and focused strictly on IT services). There was no product talent. “We had to learn everything. And we believed without doing we cannot learn. So, whether we do it right or not, we have to do it.”

Hyther Nizam joined the organisation along with Mani in 1998. He said the philosophy in Zoho was “if you want to teach them swimming, push them into the swimming pool.” He recollects an incident that happened in the early days. “There was an important call with a key OEM customer. Kumar generally takes these calls. One day, a few minutes before the meeting was about to start, he said to us, ‘you handle the meeting,’ and left the room.” Nizam and Mani managed it well enough. Besides the confidence, a key learning for Nizam was that the customer ultimately wants the problem to be solved. Nothing else matters.

In the early days, Zoho, along with other Chennai-based tech companies such as Banyan and Midas, was working closely with IIT Madras, which in turn was working closely with Analog Devices. When Ray Stata, founder of Analog, visited Chennai, the CEOs of the companies made presentations. One would have expected Sridhar, or Kumar, to do that for Zoho. But Kumar insisted that another engineer Rajesh Ganesan, an MCA from Madurai Kamaraj University, do it. “You worked on it,” he explained. Rajesh now heads ManageEngine.

The culture persisted through the years—and it helped create the “Zoho mafia”, people who worked in Zoho and went on to set up their own companies. According to Bain & Co’s 2021 India SaaS Report, 133 former employees of Zoho founded new companies. The most prominent among them is Girish Mathrubootham, who founded Freshdesk and listed it on Nasdaq last year. In an interview to The Economic Times, Mathrubootham said, “My learning experience at Zoho was great. At Zoho, I enjoyed a lot of operational freedom that allowed me to experiment and learn. I am proud of the culture that we had at Zoho. There was a strong sense of ownership and pride.” Other entrepreneurs have shared similar stories.

This kind of freedom comes from trust. Sometimes in organisations, people start with low levels of trust, and over time strengthen it. (Consider, for example, NR Narayana Murthy’s famous dictum at Infosys: “In God we trust, everyone else, bring data”.)

“At Zoho, we start with the highest level of trust,” Rajesh said. “We trust them to do their job; trust their instincts, trust their intentions.” Failures don’t bring down that trust, he added. But repeated failures, and evidence of their not being sincere enough might.

“It’s not as if The Wall Street Journal will carry a story on its front page saying, ‘Zoho tried and failed’”

When you want to learn by doing, you have to be very tolerant of mistakes, Mani said. Sridhar often says it’s not hard in the context of Zoho. “It’s not as if The Wall Street Journal will carry a story on its front page saying, ‘Zoho tried and failed’,” is one of his constant refrains.

Not long ago, Nizam started and worked on a product called Zoho Challenge, an online assessment tool. It failed to take off in the market. It was not even driving traffic. And Zoho decided to shut the product down. “My biggest concern at that time was not shutting the product, but communicating it with the engineers who worked on it. They gave their best, and I had to make sure that they didn’t see the decision as a reflection of the work they put in. Failures simply happen in this business.”

“Technology problems are easy. Business problems are hard. People problems are impossible. What makes or breaks companies is how you deal with people,” Rajesh said.

It’s easy to appreciate what Rajesh says when one ponders on how to handle mistakes, in a mistake-tolerant culture such as Zoho, when mistakes can be costly. Mani says, “We want to build a mistake-tolerant culture, but we don’t want to ship that to customers. Don’t punish anyone for mistakes, but learn from the mistakes.”

Zoho doesn’t measure performance. Sridhar believes that the idea of ‘measure and manage’ (“pushed by Harvard Business School, and exported all over”) led to the downfall of American corporations. He himself is quantitative (one can’t crack IIT-JEE without being quantitative), but he knows the limitations of numbers. They fail when it comes to human beings. To sceptics, he recommends a book The Tyranny of Metrics written by Jerry Z. Muller, an academic who went to Columbia.

In it, Muller writes, “There are things that can be measured. There are things that are worth measuring. But what can be measured is not always what is worth measuring; what gets measured may have no relationship to what we really want to know. The costs of measuring may be greater than the benefits. The things that get measured may draw effort away from the things we really care about. And measurement may provide us with distorted knowledge—knowledge that seems solid but is actually deceptive.”

Instead of numbers, Zoho relies on a culture of open discussion and honest feedback. Nizam says, there will be criticism. “You have to develop a thick skin. It’s far better for the errors to be pointed out by your colleagues than by your customers.”

It uses the approach right when it recruits employees. Zoho, first out of necessity than out of choice, went to campuses that other technology companies ignored. It doesn’t ask for a mark sheet. It doesn’t care if a student had failed in all his exams. Most of its employees come from villages and small towns. They learn their trade—coding, and product management—on the job, guided by seniors, the same way Kumar trained the initial set of employees.

In 2019, at a TIE event in Chennai, an entrepreneur, Chandu Nair, asked Kumar what it felt like to be the younger brother of Sridhar who had built a global company. Kumar replied that even when he was in school, Sridhar was an outlier. He always came first, by a large margin. Kumar’s teachers used to compare him with Sridhar, believing they were motivating him. But, he didn’t want to stress himself out. The one person who didn’t compare him—or any sibling against the other—was his mother, Janaki Vembu. She had the same trust in each of them.

Kumar applied this insight at work. “Each person is unique, even when they are from the same family, even if they grew up in the same house, and even if they are brothers and sisters. In the workplace too, each person is unique with their own strengths, weaknesses and baggage. You can’t have the same rules for everyone. The best thing you can do is to listen,” he said.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit the world, it changed a lot of assumptions behind nurturing this kind of culture—teammates, sitting next to each other, discussing, exchanging ideas, and solving problems in a spirit of camaraderie.

At that time, this principle—of listening to employees, and making it easy for them to give their best—helped Zoho along the way.

Pivoting to a new organisational model

As Zoho expanded, instead of building a campus within the city, it tried to go as far away from the city as possible. The employees benefited from cheaper rents and a better quality of life. “We wanted to have a concentration of people, because people bump into each other, and there is an exchange of ideas,” Davey said.

There was a feeling of community. Hariharan Muralimanohar, who heads marketing for Zoho One, said, “Whenever Sridhar was here, we had these open house sessions. There is a banyan tree on the campus. We assembled there and anyone is free to ask their questions. He answered them all.”

When he talks to his colleagues, conversations are peppered with stories from the history of technology and business, of nations at war and peace. The philosophical insights often are drawn from the teachings of the Buddha, Sridhar’s favourite philosopher.

It was again through these physical interactions that knowledge has been passed on from one batch to the next. “It’s not something you plan. When you put a person next to an experienced person, and they talk to each other, there is some learning going on there, as if through osmosis,” Sridhar said.

(Zoho’s logo, designed by its creative director, Raffic Aslam, reflects the idea of playfulness, and informal learning.)

However, Covid disrupted all that. Sridhar, who has a reputation for seeing farther than the others, saw what was coming. He closed Zoho offices and asked the employees to work from home. However, they, used to learning from each other—accidentally and informally—missed that aspect in an online only environment.

[Zoho’s Tenkasi office]

“So, we responded by renting out available spaces—homes, halls, etc—and converting them to rural offices,” says Davey. During the pandemic it worked. But, as employees started returning to Chennai, Renikuda and Tenkasi (its three large centres), the small centres with five to six people didn’t make sense (sometimes there were just one or two persons there). These centres didn’t have the required scale to offer some of the services employees in the bigger centres get—pick up and drop, a variety of free food, etc.

As a result, it is pivoting to a hub-and-spoke model, in which each rural centre will be connected to a bigger hub in smaller cities such as Madurai and Coimbatore. Those who work in smaller centres would go to the larger hubs a few days a fortnight or a month.

These moves addressed the needs of employees who wanted to continue the arrangement they had during Covid and at the same time get the benefits of a larger centre—the facilities, informal face-to-face conversations with more experienced employees, etc. “We are learning, we will know how well this works eventually,” Davey said.

Nizam says two things, in particular, will help. First, keeping the organisation flat—which will allow direct interactions between those who are seeped in and even shaped Zoho’s culture, and the freshers. (Sridhar’s Open House sessions, which is one dimension of this, have moved to Zoho Meeting, its video conferencing platform.)

The second, Nizam said, is through the new communication tools—such as Zoho Cliq.

“I believe rural areas can now compete. Because once the fibre optic cable is laid, you have access to information”

In some cases, these tools are not the “next best alternative” to physical meetings, but an improvement over physical meetings.

“With these, it's much easier to tap into the expertise in any part of the organisation”, Davey said. “For example, you need some legal expertise, you need some clarity on privacy, all you have to do is to add the person to your group, and it's likely they will respond. This was not possible earlier. Some decisions that used to be top down earlier, are becoming bottom up. Obviously, at some point one person or a group of people will have to decide, but the way it happens has become far more bottom up, because these tools make it possible.”

“I believe rural areas can now compete,” Sridhar said. “Because once the fibre optic cable is laid, you have access to information. Previously, we were denied an opportunity because we just didn't have access. Now we have it. The rest is creating a team, a culture that wants to do the best. That is the critical part, not access to information. For example, now I can set up a team and say we want to create the best database in the world. If they have that motivation, if there are some talented people to guide it, you can actually do it from anywhere.”

Often the best way to nurture this kind of culture is to bring in people when they are young and open to learning. Zoho has been doing it through Zoho University (now called Zoho Schools of Learning).

Nurturing critical thinking

The idea behind Zoho Schools is simple. Get them young, go to high schools, select students (typically poor, who might not even attend college because of family circumstances), teach them the skills to become an engineer, and absorb them as trainees and eventually as employees.

The initiative started small with five students—all from poor families, studying in local government-run schools, and put them on to training. They get a monthly stipend of Rs 10,000 (now) and free food. In twelve months, they get hired by product managers, and join their team as trainees, and in another six to twelve months they become regular employees—in most cases, even before they turn twenty.

Over the years, the programme has expanded. For its recent batch over 13,000 students applied for 125 seats. In a sign of its success, it’s not only the poor who are applying. Students, from middle-income families, who would have gone to a university anyway are giving it a shot too because they see more value in it.

In the US, Thiel Fellowship, run by the maverick investor Peter Thiel, offers grants to students to drop out of college to become entrepreneurs. It was motivated by Thiel’s disillusionment with higher education in the US. “There's been an incredible escalation in price without corresponding improvements in the product, and yet people still believe that college is just something that you have to do,” Thiel said.

There are more differences between Zoho Schools and Thiel Fellowship than there are similarities, but there is a common theme: how Sridhar and Thiel view higher education.

When Sridhar was in his eleventh standard, one of his classmates challenged him, saying that for all his good marks, he wouldn’t be able to get into an IIT, Indian Institute of Technology. Sridhar had never heard of IITs till then. Soon, he enrolled himself in a coaching class, cracked the JEE, and entered its Chennai campus for a BTech in electrical engineering.

The institute left him disappointed. In the eighties, attendance was not compulsory at IIT Madras, and he spent most of his time in the library reading books on philosophy, economics and society by authors ranging from Ayn Rand to Bertrand Russel and George Orwell. They were his best friends.

The classroom lectures didn’t appeal to him, because they were not practical. He wrote an article in the campus newspaper arguing that IIT was taking in some of the smartest students in India and wasting their time. “We are not building anything. We sit in classrooms competing for useless grades,” he said. It kicked off a huge debate at the campus then. (His rebellious streak was not restricted to the campus. Once after getting into an argument with his father about religious rituals, he discarded his sacred thread, left his home, and sustained himself by taking classes for school children. The father and son made up soon after. A few years ago, IIT gave him its Distinguished Alumnus Award.)

Despite his reservations about grades, he scored well in exams and won a place at Princeton to do a PhD on the strength of his transcripts. He was not impressed with Princeton either (except that he met Pramila, his future wife, during those days).

His discomfort with academia intensified after he joined Qualcomm when he got to work with smart engineers and he saw the gulf between what was being done in the real world, and what the academic institutions were focusing on. He never prefixed a Dr in front of his name nor used his PhD credentials anywhere. “My mental liberation came when I left the system,” he said in a speech at IIT-Madras. He burnt his PhD thesis as a symbolic act.

Later in Zoho, when they were hiring engineers, he found the same disconnect between credentials and talent. Engineers who scored dismally at college were performing exceedingly well at their jobs. Kumar had demonstrated that it’s possible to train world class product managers on the job. Another colleague, Rajendran Dandapani, who dropped out of IIT Madras, also had similar views on education. (Rajendran is married to Sridhar’s sister Radha, who leads Zoho Mail in the company.)

All these culminated in Zoho Schools. (Rajendran heads it now.) The school follows a flipped model of education, Davey said. The students watch videos on coding at their own pace and work on projects in class, sometimes individually and sometimes in groups, guided by teachers. There are no exams, no grades, and much like it happens in Zoho, teachers assess students throughout, guiding them, and providing them support.

The key to Zoho’s approach is that the knowledge comes with the context, Mani said. “They get to apply what they learn. Otherwise, they might forget. For example, we don’t teach them ‘pricing models’ when they are learning to code. But when they really have to work on pricing a product, they get a lecture, and a senior manager to guide them through the process.”

Often, learning happens when there is skin in the game. It hit Mani when he was two years into Zoho. Initially, he would do his job—programming—and switch off at seven. Things changed when he was given more responsibilities. He had to think through the questions deeper, ask for guidance, and get things done.

In 2014, Sridhar went to IIT Madras to share his story, and by extension, Zoho’s story, with an audience comprised mostly of students there. He was accompanied by some of his teammates from Zoho. One of them was Saroja who studied at Zoho Schools. She was already working on compilers for a new programming language that Zoho is developing, a project led by Sridhar. “She is formidable,” Sridhar informed the audience. “She is just 20, younger than most of the students here,” he said.

It’s safe to assume that pointing it out might not have landed well with at least some in the audience.

This competitive streak is reflected in some of the battles he has fought for Zoho.

Business as war

“Don’t let anyone bullshit you that business is all about cooperation. Business is war. Think of yourself as a warrior. You have to fight for your customers. You have to fight your competitors.”

~ Sridhar Vembu, 2015 Zoholics

Sridhar has scars to show from these battles. Consider how Zoho reacted when it sensed Freshworks, founded by Mathrubootham, was targeting Zoho customers using Zoho data. It sued Freshworks for trade secret misappropriation even as the latter was working towards its IPO. Freshworks settled the case outside the court, saying one of its “former sales employees, using his spouse’s computer without her knowledge, wrongfully accessed and used Zoho confidential information relating to sales leads”.

Similarly, his fights with Salesforce took place in the open. He regularly mocked Salesforce’s bloated business model, through ads and blog posts saying its customers are paying for its expensive acquisitions and ads. Sample this from a 2008 blog post written by Sridhar. “Salesforce spends nearly 8 times on sales/marketing as it spends on R&D. Sounds to me a textbook definition of ‘business model bloat’. If you are a customer of Salesforce, it makes you feel really happy that the company spends 8x on selling to you as in writing the code, right?”

Later, in 2013, Sridhar took on patent litigant Versata Software which said Zoho’s mobile apps infringed on its patent. Rather than settle outside the court (which it could have by buying a licence from Versata), it fought the battle in court for years and won the case. Not satisfied with the victory, Zoho sued Versata demanding it pay its legal expenses. A year later, court-ordered Versata to pay $60,000 to Zoho, far less than it had spent fighting the battle. But, Sridhar had made his point.

“But it's a good war. When businessmen fight, it’s good for the customers”

During the 2015 Zoholics event, its annual user conference, Sridhar said, business is war. “But it's a good war. When businessmen fight, it’s good for the customers.”

Since he moved to India, the platforms on which Sridhar spoke became far more diverse. He has always viewed business as a part of the broader economy and society, and therefore, the subjects that he speaks about extend to larger topics.

What you hear is what you get

I don't decide my views based on Twitter attacks. If you dislike which events I attend, please do what your conscience dictates and I will do what mine dictates. We earn our daily bread due to our work and we will continue to do quality work. I won't be responding to attacks.

~ Sridhar Vembu, Jan 2020, Twitter

Last month, Sridhar came across a piece in Outlook magazine written by a graduate student of South Asian Studies at Columbia University that explored the link between Ayurveda and politics, especially nationalism.

His tweet and subsequent exchange with Sree Sreenivasan, managing director of Cronkite Pro, a part of Arizona State University’s Cronkite School, were on the surface about the dynamics of business, but the political undercurrents are hard to miss.

Early in 2020, when many saw Sridhar merely as a successful tech entrepreneur who had settled in a village in Tamil Nadu, he agreed to speak at an RSS event. There was a backlash, online protests and calls to boycott Zoho products (that was also the time when Zoho was stepping up on the Indian market, especially for its Zoho One). Many (who didn’t know Sridhar well enough) believed he would pull back. He didn’t. Zoho issued a statement saying he would speak only about rural job creation, and nothing more.

Later, he told Forbes India, “The RSS is doing a lot of good things on ground. I have seen hundreds of volunteers who are going around and distributing food during this time and it is not visible to everyone. And I’m not going to forbid this group just because some people will take offence on Twitter. I’m definitely not going to give authority to anyone to enforce where I should be. They have the liberty to do what they want so even I’m at liberty to speak [what and where I] want… that’s my attitude and that’s freedom.”

One person who has had several conversations with Sridhar over time said, “Sridhar doesn’t have any strong ideological bent. He is pragmatic, above all. What I think happened is this: the left ecosystem kept pushing him away, and the right welcomed him with open arms. Many things that he talks about—building in India, investing in local capacity, being rooted in local culture—align well with the right’s worldview. But some of them (in the right) miss the point. For example, in Japan (where Zoho has a centre, again in a rural area) he would say they should be rooted in Japanese culture. But it is what it is.”

Even during his school days, Sridhar was interested in politics and devoured Tamil magazines. One of his favourites was Thuglak, edited by Cho Ramaswami, a lawyer, playwright, comedian and astute observer of Indian politics. Cho passed away in 2016. Sridhar is in regular touch with its current editor, S Gurumurthi, a chartered accountant and the co-convenor of RSS affiliate Swadeshi Jagran Manch. Some of their views—especially on creating local capacity—align.

The right, it can be argued, has been embracing him even closer. He was awarded a Padma Shri in 2021. A month later, he was invited to be a part of the National Security Advisory Board, led by Ajit Doval. And this was followed by a mention by the Prime Minister in Mann ki Baat last month.

So what’s next?

No doubt Sridhar Vembu’s courage of conviction will earn him kudos. But eventually, it needs to sustain performance over the long term.

Being privately held, Zoho doesn’t disclose its revenues. According to financial statements accessed by Entrackr from the Registrar of Companies, it reported revenues of $677 million in FY 2021 ($570 million in FY 2020). Its EBITDA margins were 50% in 2021 and 33% in 2020.

On the other hand, Freshworks, which took a divergent path, reported revenues of $371 million in CY 2021. It reported an operating loss of $204.8 million during the year. In terms of revenues both Zoho and Freshworks are small, compared to Salesforce.com. Salesforce reported $21.25 billion in revenues in FY 2021.

In the coming years, the focus will be primarily on three areas, Davey said.

First, instead of adding more products (Zoho One has over 40 distinct products on which an entire business can run; Zoho itself runs on Zoho products), Zoho will add more features, and integrate more workflows into them. One example is supporting more currencies. Second, solutions catering to specific industries (verticals in industry lingo), such as retail or pharma or logistics. Right now, Zoho products are focused on horizontals (HR, Finance, etc). As they listen to their customers, add more features, and integrate more workflows, they will be in a position to target specific industries. Finally, the marketplace. Zoho already has a platform called Catalyst, which allows developers to build specific products and sell them to customers. That will expand.

Zoho was always an engineering-focused company. The new focus areas would demand more domain expertise. Davey says its recent hiring reflects those changes.

The short and medium-term strategy is just one part of it. Its long term bet is in investments in new technologies. Davey oversees Zoho Labs which is building new tech, including AI and ML. Sridhar spends a good amount of time with engineers, and specifically, leading a team that is building a new programming language. It’s called Pali, the language in which the Buddha preached.

Echoing the words of Soichiro Honda, Sridhar said the output of the R&D gets embedded in products (thus its grammar engine found its way into email and chatbots) and in some cases, it can be a kernel for a new product line. Some of the investments are in pursuit of a high margins-low price strategy. For example, his interest in semiconductors comes from the realisation that the performance will increasingly depend on the full stack of infrastructure, rather than the performance of the chip alone (since Moore’s Law is weakening). A business that looks to deliver competitive prices and still have high margins, will have to invest in such infrastructure.

Consider some of the investments that Zoho made in the recent past—a startup making chipsets for 5G base stations, a venture developing India’s MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) machines, a robotics firm (along with Srinivas Kanumuru, a co-founder of Zoho), a startup that is building a high-speed optical sorting tech, and another that is building technology that can replace manual scavenging.

In 2019, Ramakrishnan Kalyanaraman, MD of Spark Capital, attended a small gathering in Chennai in which Sridhar spoke. Sridhar mentioned he had hurt his back, and was at a hospital taking an MRI scan. He noticed that there was nothing in that room that was made in India—and there was no reason why India cannot make it. Ramakrishnan said, this is something we would have noticed too, and we would have left it at that. “But he goes into it and then tries to see ‘what can I do? Is there a way in which I can kind of bring about a change?’ And now he has the resources to bring about that change.”

“Whenever I look at an unfamiliar product, I immediately go into an investigation… I have like a list of 500 ideas”

In that speech, Sridhar explained his approach to product management. “Whenever I look at an unfamiliar product, I immediately go into an investigation: Who made it? What is the revenue? What’s the profit margin on it? What’s the gross margin on it? What are the components in it? That’s what I do relentlessly. I have like a list of 500 ideas. I’ll probably die before I’m finished with all of them, which is good because that will keep me busy.”

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

Post script: We live in the age of spreadsheets and pitch decks, and believe that the complexities of a business can be tamed by numbers crunched through sophisticated models and narratives that follow a template.

But Zoho’s story highlights that a business is shaped by people and their convictions, by the places and their peculiarities and by the period during which the entire drama is played out.

It’s not all chaos, but it’s an inversion of the way most startups work. Typically, an entrepreneur identifies a market opportunity, big enough to attract a VC; gets access to tech and people who can solve the problem, raises funds, and if all goes well, starts scaling up. The faster the better.

Sridhar, on the other hand, puts culture first. Get people who have a shared vision and values, out of that emerges a strategy, and that’s followed by execution. In Zoho’s case, as in Honda, these people are typically passionate about tech (or discover their passion in tech even if they come with a blank slate to Zoho School or Zoho itself as a fresher).

This allows him to take long-term bets, and make investments in what seems to be disconnected or far removed from Zoho’s business (MRI machines or chipsets). That’s a way to attract and retain talent. Engineers like to work on tough problems.

Keeping people and values as a starting point also meant that while founders separated over differences in strategy, they remained friends. Kumar is still involved with Zoho Corp. He calls Tony Thomas “my personal daily Buddha” with whom he talks almost daily to seek his wisdom. He co-invested in a robotics company with Srinivas Kanumuru.

Mathivanan V, who joined the company when it was still operating out of the first floor of Sridhar’s parents’ house in Tambaram, in Chennai says each one of the founders and early employees brought their own strengths into the company. And that helped build a culture that’s hard to define. “I can try and explain, I can tell you several stories, but they won’t capture the culture here,” he says.

Rajesh says that he is not sure if another Zoho can be created even if the same team came together yet again.

The point of Zoho is not to create another Zoho, but to show the value of questioning the accepted wisdom, treading your own path, being your own light.

Earlier this year, Sridhar spoke to students of ACJ-Bloomberg, the college of journalism, based in Chennai. He encouraged would-be journalists to question the conventional narratives. “In business, you make money by betting against a narrative that’s false,” he said.

It’s a version of the advice he gave to students at IIT Madras in 2016. He said, “To make progress in life, be sceptical, question everything, including whatever I say.”

Still curious?

Listen to a conversation between Sridhar Vembu and Sharad Sharma (or read 5-minute takeaways) where they talk about creating resilient, uniquely Indian companies; questioning buzzwords and received wisdom; investing in deep tech; and more.