[By Yann (talk) - Scanned by Yann (talk). Public Domain]

Good morning,

On the surface it might seem as if Mahatma Gandhi, Franklin Roosevelt, Lee Kuan Yew, Narasimha Rao and Sumant Moolgaokar don’t have much in common. They lived in different times, different environments, faced different types of challenges. That’s exactly the diversity we were seeking while putting together this list, because the world is facing a huge disruption, not only because of the pandemic, but also because of technology and geopolitical shifts.

The lessons from their lives are enduring. Here are six.

1. Every small thing matters when you are building a culture of quality

Last year, we published an extract from Arun Maira's book on how the Tatas nurtured. The thrust of the piece was captured in a quote by quality guru Joseph Juran: “Quality is not in the numbers. It is in the people.” But, how do leaders create a culture of quality? Here's an anecdote from the piece. It's about the legendary Sumant Moolgaokar who led TELCO.

[From Pixabay]

“Sumant Moolgaokar was in his seventies when TELCO entered into the agreement with Honda. Still, his mind and his spirit were as sharp as ever. The Honda directors who met him respected him greatly. They said they would be honoured if he would come to Japan to sign the agreement with them, where they could also show him their factories and research centres. I also accompanied him. He was impressed with the cutting-edge technologies he saw there.

“The morning of our last day in Japan, I went to the small shop in the Okura Hotel, where we were staying, to buy some ball pens and Japanese stationery as souvenirs for my children. There I met Sumant Moolgaokar. He was examining something very carefully. It was a pair of ceramic scissors. He beckoned to me to come over. He showed me how beautifully the scissors were designed—its simplicity and its elegant shape. ‘It has ceramic blades,’ he pointed out, ‘which will not blunt.’ Then he showed me how cleanly the scissors cut a piece of paper. And he handed them to me and said, you try too. While he watched, I did.

“‘This is high-quality, Maira,’ he said, and went on to purchase the scissors to bring back to India. There he had them on his office desk for the next few years, and would delight in cutting open envelopes with them whenever he had to.”

Read the full essay by Arun Maira: To learn fast, go to the real place, look at real things, talk to real people

2. Empathy is a key to communication

As it was getting clearer and clearer that managing Covid-19 will demand extraordinary leadership, K Ramkumar, founder and CEO, Leadership Centre, wrote an essay capturing lessons from leaders who faced and overcame life and death crises. One of them was US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who led America and the world out of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

[From Pixabay]

“Messaging is not speech making. It is the empathy which Roosevelt brought to American citizens in the midst of the Great Depression. He conversed every evening at 7 pm with ten families live on the radio—for 1,000 days. Every citizen felt they were talking to their President every day, that he was listening to them about their fears. They were reassured and infused with a daily dose of hope.

“In this pandemic, it will be the FDR type of business leader, who is listening to, conversing with, reassuring and nudging with care the last person in the field, who will rally her troops. The speech making, target slave-driving, type of business leader (who says get me more business somehow, I don’t care if you get infected) will appear to win in the short term, but will lose his best and the brightest in the months to come.”

Read the full essay by K Ramkumar: Lessons in crisis leadership from four stories of survival

3. Tinkering is often the best way to make progress

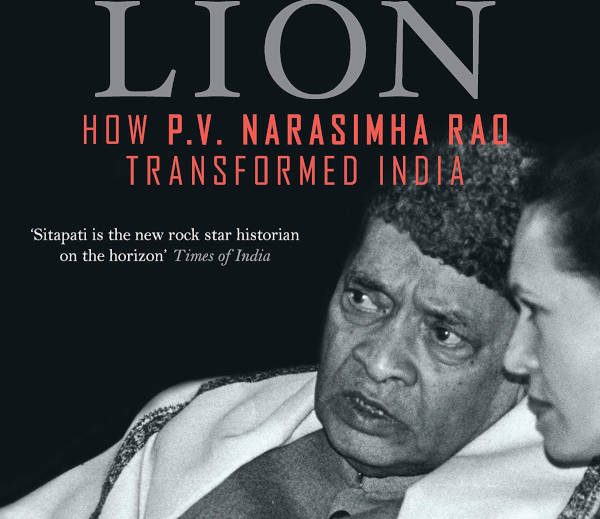

In his insightful study of the architect of India’s economic reforms, Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Transformed India, Vinay Sitapati pointed out that the right moment doesn’t matter. “Four prime ministers before Narasimha Rao had been presented with the right ‘moment’—in terms of favourable external winds, well-sketched internal ideas, and opportunistic crises—to renovate India. They had been unable to make use of these opportunities.” What made Rao tick?

“P.V. Narasimha Rao was born a fixer. When something didn’t work, his first instinct was to open it up, figure out what was wrong, and make marginal improvements to solve the problem. As a young man in 1957, he noticed a malfunctioning water pump. He opened it, identified the problem, fixed it, and complained to the manufacturer. As chief minister in 1971, he had observed evasions of his cherished land reform policy. He had tweaked the law in ways that ensured their compliance. Two years later, he noticed that planting rice in his village was not remunerative. He bought more valuable cotton seeds from Gujarat. When he realized that the cotton plants self-pollinated and weakened the new crop, he ingeniously fixed a straw on the plant so that pollen would fly elsewhere. As Ramu Damodaran says, ‘Rao was a jugaad reformer. He made the best of what he had.’”

Read a longer excerpt from Vinay Sitapati’s book: The man who knew tomorrow

4. Pragmatism trumps ideology

Harvard professor Joseph Nyeonce described Lee Kuan Yew as a man “who never stops thinking, never stops looking ahead with larger visions. His views are sought by respected senior statesmen on all continents.” One of the reasons why leaders—from all political backgrounds—sought Lee’s advice was that he was pragmatic.

[Photograph: US Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen (right) meets with Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew (center), of Singapore, and Singapore's Ambassador to the U.S. Chan Heng Chee (left) on February 29, 2000]

On his first death anniversary, Founding Fuel compiled a few defining lessons from his books, interviews and speeches. Here’s one on pragmatism.

“My life is not guided by philosophy or theories. I get things done and leave others to extract the principles from my successful solutions. I do not work on a theory. Instead I ask: what will make this work? If, after a series of solutions, I find that a certain approach worked, then I try to find out what was the principle behind the solution... Presented with the difficulty or major problem or an assortment of conflicting facts, I review what alternatives I have if my proposed solution does not work. I choose a solution which offers a higher probability of success, but if it fails, I have some other way. Never a dead end.”

Read the compilation of lessons by NS Ramnath: Lee Kuan Yew: A leadership style that got results

5. Great leaders make impact by building on strengths

India has had several distinguished people as its president. But there was none like Abdul Kalam. In his column Charles Assisi draws insights from Peter Drucker’s influential paper Managing Oneself and how Kalam’s life reflected some of the key lessons there.

“Drucker writes: ‘Most people think they know what they are good at. They are usually wrong. More often, people know what they are not good at—and even then more people are wrong than right. And yet, a person can perform only from strength. One cannot build performance on weaknesses, let alone on something one cannot do at all.’...

[Photograph of Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam by Bhaskar De under Creative Commons]

“President Kalam got it intuitively. That is why he had it in him to acknowledge that the office he occupied was a largely ceremonial one. But unlike many of his predecessors who accepted the weaknesses in the system and occupied it as a ceremonial position, President Kalam reframed the problem to ask of himself what strengths that office and its grandeur could possibly confer on him.

“President Kalam’s ambitions and values demanded he engage with the finest minds that have it in them to build a prosperous and equitable nation. When viewed from an ethical perspective, his impressive title notwithstanding, it insisted he spend time with minds that can be moulded as well.

“That is why he spent time with at least three schools on average every day, filled with impressionable minds. He wanted them to listen and buy into the limitless possibilities. He did it because when he looked at himself in the mirror every morning, he could tell himself he was living a life true to all that he stood for. The mirror doesn’t lie.”

Read the essay by Charles Assisi: Why Abdul Kalam continues to matter

6. Be authentic

Ever since the pandemic started we have been surfacing some of the best things we have read, heard or seen online in our daily newsletter. One of them is from a conversation Nitin Paranjpe, COO, Unilever, had with Anil Sachdev, founder and chairman at the School of Inspired Leadership.

[By Yann (talk) - Scanned by Yann (talk). Public Domain]

“All of us know Mahatma Gandhi. And one thing I've always wondered is what might have happened when he set out for the Dandi march, and a day later he discovered that there was no one else walking behind him. Would he have stopped? Or was he the sort of person who would have walked and tried to make salt alone. I feel he'd have gone and done it all alone. And I suspect most people would have seen him like that and because they saw in this man, a person with such conviction, such belief that it inspired all. That's why he had hundreds of thousands of people following him. Because he was willing to follow this belief system, irrespective of anything else. So I would say to everyone. I don't know whether I can ever be like that. But I'd say, have a point of view, and be authentic to yourself. I don't know whether you will become a leader, but you will be true and that's your best shot.

- Being authentic may not make you a leader. But I can guarantee you, not being authentic is certain that you will never be. So, your best chance is to be yourself.

- Don't be afraid of expressing a point of view. Having a point of view once again doesn't guarantee that you're a leader. You become a leader when the point of view is different, it's inspiring, makes people say wow, that's good and people then want to follow.

- Great leaders don’t become great leaders, because they have followers. They become great leaders because they follow—they follow their beliefs.”

From: WFH #110: Nitin Paranjpe on why millions followed Mahatma Gandhi