Across India, there are places where history, culture, and resilience come alive — not in monuments alone, but in spaces still bustling with life.

We invited a few members of the Founding Fuel community to contribute to this list of sites that played a vital role in shaping modern India. These go beyond the obvious historical landmarks, offering travellers a guide to lesser-known but equally powerful places that tell the story of our republic’s evolution.

We ran a similar project in 2022 for India@75, and this year we return to it with fresh eyes and new discoveries. Each of these 12 locations tells a story of people shaping their own destiny.

Connemara Library, Chennai: A City’s Bookkeeper

By NS Ramnath

[Photo by Jm.kaarthik, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Tucked into the cultural heart of Chennai’s Egmore, alongside the Government Museum and the National Art Gallery, the Connemara Public Library is more than a quiet refuge for book lovers. It is one of India’s four National Depository Libraries, which means it receives a copy of every book, newspaper, and periodical published in the country. Its shelves hold over 900,000 works, from a 1608 Bible to an atlas printed for Queen Victoria.

The library’s story began in 1860, when Captain Jesse Mitchell, a British Army officer who served as Superintendent of the Government Museum, started a modest collection within the museum. He stocked the library with surplus books from England’s Haileybury College, which trained Indian civil servants. By 1890, Lord Connemara, then-Governor of Madras, pushed for a grand public library and laid the foundation stone for the striking Indo-Saracenic building. It opened in 1896 and quickly became a city landmark.

The site itself was steeped in history. As the city’s historian S. Muthiah writes, the library grew in the grounds of what was once "The Pantheon," a place for high-society entertainment. Muthiah notes this was where Lord Cornwallis was celebrated after his military campaign at Seringapatnam, and Lord Wellesley after Assaye.

Over the decades, the library evolved with the city. In 1929, its first Indian librarian, R. Janardhanam, pioneered open-shelf Browse by moving books from locked cupboards to accessible racks.

After Independence, the Connemara played a pivotal role in shaping India’s library network. It was central to the Madras Public Libraries Act of 1948, the first of its kind in India, and became the State Central Library in 1950 before being designated a National Depository Library in 1955. Leaders like C.N. Annadurai and C. Rajagopalachari once studied within its walls, as did many scholars and writers. This tradition of connection spans generations; T. Ramakrishnan, a senior journalist with The Hindu, and the author of Cauvery — A Long Winded Dispute, remembers visiting as a schoolboy with his father, the celebrated writer Ashokamitran, and has been a member ever since.

For Ramakrishnan, the appeal is not just in the books but in the setting. “The entire campus — the library, the museum, the galleries — has a quiet, salubrious charm that appeals to your heart in a way modern, flashy buildings never can,” he says. And beyond its utilitarian role, he believes the Connemara offers something rarer: “It’s not just a place where books are stored, or journals are collected. It’s where you experience the sheer pleasure of acquiring knowledge, sometimes for its own sake, and, something I fear we are slowly forgetting.”

The library continues to evolve. There are plans for new sections. Digitization of some of its rare books is ongoing. The library, which started with surplus books from a faraway institution that trained civil servants, continues to attract a large number of civil service aspirants to this day.

Sriharikota, Andhra Pradesh: From Makeshift Bridges to Mars

By NS Ramnath

[Photo by Indian Space Research Organisation (GODL-India), GODL-India, via Wikimedia Commons]

Today, Sriharikota is synonymous with India's space triumphs—Chandrayaan’s lunar mission, the Mars Orbiter’s historic journey, and over 100 successful launches. But the real story of this spaceport lies in its humble, almost comical beginnings. The book From Fishing Hamlet to Red Planet: India's Space Journey, a collection of stories and interviews published by ISRO, captures its early days. The “fishing hamlet” in the title refers to Thumba, near Trivandrum, but Sriharikota had even humbler beginnings.

In March 1968, when scientist E.V. Chitnis identified this remote island off Andhra Pradesh as India's future launch site, it was inhabited by Yenadi tribals and used for eucalyptus plantations. Getting there was an adventure. When Dr. Vikram Sarabhai, the father of India's space programme, made his first formal visit in May 1969, his team had to cross the Buckingham Canal on a makeshift bridge of boats lashed together with wooden planks. Jeeps got stuck on muddy roads across Pulicat Lake, and one vehicle's axle touched the ground under passenger weight. Local officials cleared paths by shouting “deputy collector is coming”, since nobody would recognize Sarabhai's actual designation.

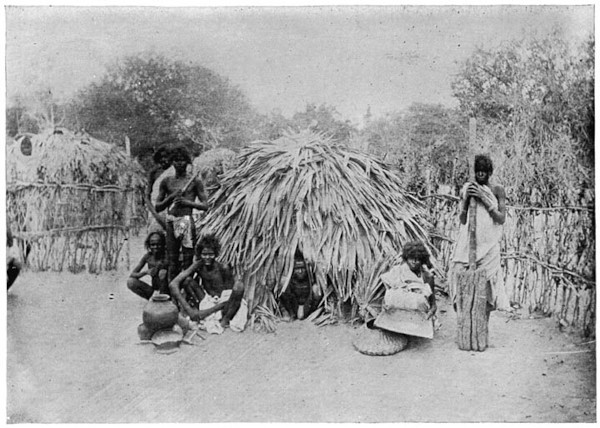

[Yenadi hut. Photo by Edgar Thurston assisted by K. Rangachari, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

Civil engineer R.D. John became the “first man on the field”, building basic infrastructure from scratch. The site was connected to the mainland by over 400 telephone poles strung across the lake. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who later directed the crucial SLV-3 project, famously declared that simply getting an assembled rocket to the launch pad was “50 percent success”.

The transformation wasn't without quirks. Feral bees built massive hives on the Mobile Service Tower, making employees nervous. The Yenadi tribals, many now educated and employed by ISRO, continued living in their cyclone-proof huts. R. Aravamudan, who became director in 1989, felt like the “Sultan of SHAR” in this isolated island community where ISRO had to provide everything—schools, hospitals, police, even burial grounds. Before launches, coconuts were broken for good luck, and ISRO chairmen visited Tirupati temple with rocket models for blessings.

Sriharikota was also a platform for many leadership lessons, especially when the missions failed. The first launch attempt of SLV-3 on August 10, 1979, failed spectacularly when the rocket went out of control and crashed into the Bay of Bengal. Chairman Satish Dhawan took personal responsibility at the press conference. The second attempt on July 18, 1980, succeeded brilliantly, placing India's Rohini satellite in orbit and making India the sixth nation with indigenous launch capability. Kalam was hoisted on colleagues' shoulders in celebration. Later, in 1987, Rajiv Gandhi was in Sriharikota to witness the launch of ASLV D1. It failed. A journalist remembers the maturity Gandhi displayed back then. He said, “It is only when you stumble that you can get up and walk better.”

ISRO has not only learned to walk better, it’s in full stride now, with bigger ambitions. It’s preparing for Gaganyaan, India’s first manned spaceflight, set for 2026, with astronaut training and test flights underway. ISRO also plans Chandrayaan-4 to bring back lunar samples by 2027. Plus, it’s building a new, powerful rocket (NGLV) and working on India’s own space station (BAS), with the first part launching by 2028.

ISRO allows Indian citizens to watch launches from the Launch View Gallery, which accommodates up to 5,000 people. You can register here. Registration typically opens 4-5 days before the launch.

MS Swaminathan Research Foundation: Where Ideas Take Root

[Photo from Facebook]

Drive past Chennai's Taramani Institutional Area and you might easily miss the unassuming MS Swaminathan Research Foundation campus. Yet it became an unlikely nerve centre for India's post-Green Revolution agricultural thinking, wielding influence far beyond its quiet exterior.

The foundation emerged from a deeply personal initiative by MS Swaminathan, the architect of India's Green Revolution. After retiring from his illustrious career and a stint as Director General of the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines, Swaminathan used his World Food Prize money and other awards to establish what was essentially a family foundation in 1988. The current campus was inaugurated around 1992.

Unlike the institutional machinery that drove the Green Revolution in the 1960s, MSSRF represented a more nuanced approach to agricultural development. Swaminathan, having witnessed both the triumphs and limitations of chemical-intensive farming, sought to create a space where sustainable solutions could be explored.

What made MSSRF extraordinary was its role as a convening space. Through the 1990s, the foundation hosted international conferences that brought together global experts, policymakers, and researchers to Chennai, a city that might otherwise never have seen such gatherings. These weren't just academic exercises; they were working sessions that shaped policy.

The foundation became the hub for drafting India's Biodiversity Act, with Swaminathan chairing the committee responsible for this crucial legislation. Discussions around the World Trade Organization's agricultural implications, genetically modified crops, and farmers' rights found a home here. The concepts of “evergreen revolution”, sustainable intensification of agriculture, and renewed focus on traditional crops like millets emerged from these deliberations.

MSSRF's significance lies not in grand infrastructure but in its role as an intellectual catalyst. It represented a transition from the crisis-driven Green Revolution to more thoughtful, sustainable approaches to feeding India. The foundation embodied Swaminathan's evolution from a scientist focused on immediate food security to a visionary thinking about long-term agricultural sustainability.

Following Swaminathan's passing in September 2023 at age 98, MSSRF faces the complex challenge that confronts all institutions named after their founders. When you name something as MS Swaminathan Foundation, you can't be better than MS Swaminathan. It’s a structural limitation that can constrain future growth and innovation.

The foundation's trustees, primarily family members including Swaminathan's three accomplished daughters, a health specialist, a development expert, and an economist, now carry the responsibility of reimagining the institution's role. While they bring diverse expertise, their challenge lies in translating their varied specialisations into the agricultural development focus that defined their father's work.

(As told to NS Ramnath)

The Indian Coffee House: The House That Workers Built

By Dr. N.P Chandrasekharan

[The Indian Coffee House, Trivandrum. Photo by Aleksandr Zykov, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

The Indian Coffee House is a chain of cafes, but that simple description misses the point. It is an institution started by its own ex-employees, a network of spaces that became a common room for a new nation's artists, intellectuals, and rebels. Its story is a unique chapter in India’s post-independence history, demonstrating how a space for the people, run by the people, can shape a country's cultural and political life.

Its journey began in the late 1930s, expanding in the early 1940s as the “India Coffee House”, a chain run later by the British government’s Coffee Board, established in 1942. The official mission was straightforward: to promote coffee consumption in the country. After India's independence, by the late 1950s, the Coffee Board began shutting down the coffee houses due to mounting losses.

This left its workers—many from Kerala and including cooks, waiters, and support staff with little formal education—facing unemployment. Their union leader, A.K. Gopalan, the first opposition leader in India's Parliament, offered them simple advice: form cooperative societies and run the coffee houses yourselves. They did. These workers took over the failing establishments in 1957, turning them into the “Indian Coffee House”. They were compelled to run by themselves what was once managed by educated supervisors. Against expectations, they succeeded, turning losses into profits by the 1960s.

The worker-owned coffee houses became vital public squares. They were the meeting points for artists and thinkers, the rich and the poor. In these spaces, political ideas were debated, literary movements took shape, and a culture of open conversation thrived.

While united as a cooperative, each outlet developed its own distinct character. The College Street branch in Calcutta became an iconic hub for Bengali literary and cultural life. In Delhi, the Connaught Place outlet grew into a critical center for political dissent. The Trivandrum coffee house near the railway station is an expression of the famed architect Laurie Baker’s organic style. Designed as a small, circular building, its spiral steps have seats and tables built alongside them, showcasing a unique, alternative approach to public architecture.

The history of this movement was chronicled by one of its own. My father, N.S. Parameswaran Pillai, a former Coffee Board employee, became the founder-secretary of the cooperative society in Trichur, Kerala, and also served as the manager of its first branch. He was instrumental in organising the workers’ takeover. To ensure their story was not forgotten, he authored a book titled Koffeehousinte Katha, or “The Story of the Coffee House,” which remains a crucial first-hand account of the struggle from a worker’s perspective.

The Indian Coffee House is not just a business; it is an institution where a young democracy found its voice.

Dr. N.P Chandrasekharan, son of NS Parameswaran Pillai (who cofounded Indian Coffee Houses in Kerala) is a senior editor at Kairali TV.

(As told to NS Ramnath)

Bylakuppe, Karnataka: Where Refuge Transformed into Rebirth

[The Namdroling Monastery, also called the Golden temple, at Bylakuppe]

Amidst the quiet fields of Karnataka, far from the icy plateau of Tibet, lies Bylakuppe—a town both unique and resilient. It is the largest Tibetan settlement outside Tibet, a living testament to compassion, cultural preservation, and the enduring bonds between two ancient civilizations.

After the Chinese invasion of Tibet, His Holiness the Dalai Lama fled in the dead of night, embarking on a perilous journey, crossing the Himalayas on foot with his followers. On March 31, 1959, they reached the Indian border at Arunachal Pradesh, where the Assam Rifles welcomed and safely escorted them.

In a gesture of solidarity, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru offered Dharamshala and 3,000 acres of barren land in Bylakuppe to Tibetan refugees. Over time, these townships—complete with schools, nunneries, and monasteries—have preserved centuries-old rituals, language, prayer, and traditions. The Indian government’s continued commitment to granting religious autonomy has been pivotal in nurturing this vibrant community. Today, Bylakuppe thrives as a community of over 10,000 Tibetans living in exile. It is a symbol of cultural rebirth.

The Sera Jey Monastic University was re-built along the lines of the original 15th-century Gelug monastery in Lhasa. The scholastic university houses over 5,000 monks, with many young Tibetans for whom Lhasa is not even a memory—only a distant idea of their homeland. Namdroling Monastery, also called the Golden temple, is one of the largest teaching centres of the Nyingma lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Dalai Lama, Noble Peace Prize laureate and spiritual head of Tibet, is renowned for his tireless advocacy of a non-violent struggle for Tibetan freedom. In his autobiography, he reflects on exile as a journey to discover true freedom and purpose—championing universal human values, interfaith harmony, environmental protection, and the preservation of Tibetan culture.

This February, I visited Bylakuppe with the Menlhai Jamtse Ling Buddhist Centre, Mumbai. The Lamas at Sera Jey hosted us with a warmth and kindness that left a deep impression. Under the guidance of Geshe Lobsang Tenzin La, our group was blessed with an extraordinary opportunity—an audience and teaching with the Dalai Lama at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. For a practicing Buddhist like me, it was a rare and treasured moment. We also took part in the Tara Puja at Sera Jey Monastery and received another rare audience—this time with the 104th Ganden Tripa, His Eminence Lobsang Tenzin Rinpoche, the spiritual head of the Gelug school.

The monasteries stir both faith and the senses: the resonant chants; the peal of bells and gongs; the steady turn of prayer wheels; the fragrance of incense; the golden idols, thangkas, and mandalas shimmering with intricate detail. Every ritual and sacred object carries layers of meaning.

There are 45 Tibetan settlements in India, across 10 states; the 2009 census pegs their numbers at 1,10,000 refugees.

Karnataka is home to the largest number of Tibetan refugees in India (approximately 21,300 as of 2023, according to the Indian government), followed by Himachal Pradesh (15,000). Bylakuppe, Mundgod, Dhondenling and Rabgayling are the four main towns in Karnataka that offer a glimpse of the Tibetan way of life. Mundgod is home to a cluster of seven monasteries, a nunnery, Tibetal Medical Institute. The largest and best known are Gaden Jangtse Gaden Shartse, Drepung Loseling and Drepung Gomang monasteries.

Even at smaller settlements like Rabgayling, near Hunsur town, houses are committed to keeping alive cultural and wisdom traditions through festivals and handicrafts. Palden Drepung Monastery is a key centre of learning, meditation and preservation of culture.

Though in exile, the Tibetan community radiates optimism, resilience, and unwavering faith. On Indian soil, they have preserved their culture while finding new ways to express it—offering the world a model of how displaced communities can not only survive, but flourish.

Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla: A Historic Seat of Power and Academic Research

A winding 1km-long Cyprus-lined road rises up the hill from Chaura Maidan in Shimla to Observatory Hill. At the top sits a majestic colonial-era structure that used to be the Viceregal Lodge, and now houses the Indian Institute of Advanced Study (IIAS)—one of the foremost institutions for research in India.

Post-independence, the Viceregal Lodge became the Rashtrapati Niwas, the Indian president’s summer retreat. In 1965, President Dr. S. Radhakrishnan inaugurated IIAS—converting a symbol of colonial power into a symbol of academic excellence.

Today, IIAS stands as a hub for advanced interdisciplinary research, offering prestigious associate and fellowship programmes, conducting weekly seminars, and publishing monographs, journals, and conference proceedings. Eminent thinkers such as Amartya Sen and Noam Chomsky have been associated with its work. It also houses specialised centres like the International Centre for Human Development and The Tagore Centre for the Study of Culture and Civilisation.

The IIAS library, established in 1965, is a world-class resource for scholars, particularly in humanities and social sciences. Its elaborate wood panelled walls, huge windows overlooking the well-manicured lawns and garden and a huge winding staircase leading to the basement, leaves a lasting impression on its scholars. With over one lakh books and subscriptions to several journals, it plays a vital role in supporting high-level academic research. The library has digitised rare academic and historic materials to ensure preservation and access for future generations. In 2015, I had the privilege of participating in IIAS’s month-long Associate Programme, gaining access to the library’s vast resources and participating in academic seminars. It helped me to write and present a research paper that was later published, marking a memorable and productive academic experience.

However, the significance of this Jacobethan style building to Independent India goes deeper.

The summer retreat of the British viceroys became the site for key debates on constitutional reforms, highlighting the gradual erosion of British rule. The library was the ballroom where the Shimla Conference was hosted in 1945. Leaders like Lord Wavell, Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Maulana Azad and Master Tara Singh discussed the future of India under British rule. The talks failed, and events eventually led to Partition. In the visitor’s hall stands a split table—according to a perhaps apocryphal tale, the plan to partition India was first presented on it.

This iconic building featured in Richard Attenborough’s Academy Award-winning film Gandhi, providing an authentic backdrop for scenes depicting the British Raj and the Indian independence movement.

Visitors can catch a glimpse of history. IIAS is open to the public and guided tours are offered for those interested in exploring its historical and architectural grandeur.

La Martiniere College Lucknow: A Living Restoration

[Photo from La Martiniere College Lucknow]

Perched above the Gomti in Lucknow, La Martiniere College is no ordinary school. At its heart is Constantia — a baroque palace built by French adventurer Major General Claude Martin in the late 1700s, and repurposed into a school in 1845. Today, Constantia is the beating heart of a remarkable restoration effort that has come to define the institution’s resurgence in independent India.

For decades, the building had been crumbling under the weight of its own history. Intricate ventilation shafts were choked with rubble, decorative plasterwork hidden under thick layers of lime, and even bat colonies had taken residence in its halls. The structure once described as “a dark, dingy fort” was fading into obscurity.

But in the past decade, a quiet revolution has unfolded on campus. Spearheaded by a passionate school leadership and supported by both engaged alumni and artisans whose families have worked on Lucknow’s architectural gems for generations, Constantia has been lovingly, painstakingly restored. No shortcuts. No gaudy retouching.

Stained-glass windows now throw jewelled light into the chapel. A century-old pipe organ plays once more. Forgotten motifs, carved in limestone and wood, have re-emerged. Even the palace’s original passive cooling system — clogged for a century — now works again. The soul of the building breathes afresh. The meticulous effort — from the revival of delicate wedgewood carvings to the uncovering of centuries-old decorative motifs — has been vividly chronicled in Vogue India’s feature on La Martiniere’s restoration.

Each corner tells a story. A mason named Ansar-ud-din, whose craftsmanship caught the eye of the French ambassador. Women perched on scaffolds, unearthing buried ornamentation with scalpels and needles. Dormitories and halls have been reimagined as museums and archives, without losing their character.

The effect is transformative. Former students now walk through the building with misty eyes, reclaiming childhood memories. The tricolour atop the building — which once flew the flags of the Nawab, the East India Company, the French and the British — now stands as a symbol of renewal, not just history.

Today, Constantia is a living, learning heritage site — recognised by UNESCO and open to visitors through guided tours that unlock its secrets layer by layer. For those who walk its halls, it offers more than nostalgia. It offers hope — that restoration is not about looking back, but about carrying legacy forward.

Living and Learning Design Centre, Kutch: A Sanctuary of Stitches

By Tara Sharma

[Photo from Shrujan]

The Living and Learning Design Centre (LLDC) in Ajrakhpur, Kutch, stands as a remarkable space dedicated to preserving and promoting Kutchi crafts and their creators. Conceived after the devastating 2001 Bhuj earthquake, its roots go much deeper—back to 1969.

That year, Kutch was reeling from four consecutive years of severe drought when Chanda Shroff, visiting the region’s villages, discovered exquisite hand embroidery on women’s personal garments. She saw in this artistry the potential for sustainable, dignified livelihoods, and thus Shrujan was born. Today, Shrujan works with over 3,500 craftswomen across Kutch.

In 1997, Shrujan launched its “Design Centre on Wheels” to revive forgotten embroidery traditions. Over the years, craftswomen collaborated with designers to create large textile panels representing the diverse embroidery styles of Kutch—panels that now have a permanent home at LLDC.

Spread across nine acres, LLDC features a world-class crafts museum, studio spaces, an auditorium, and a visitor’s gallery where guests can try block printing. Guided walks reveal the stories of the communities behind each craft. The current exhibition, Living Embroideries of Kutch, showcases the work of 12 Kutchi communities, pairing specially curated pieces with audiovisual displays to provide cultural context. Many of these communities trace their origins to Central Asia and beyond, bringing with them skills and motifs that have evolved in Kutch over generations.

Designed by Indigo Architects for Kutch’s hot, arid climate, LLDC’s architecture creates an immersive space for the crafts themselves. The museum block is composed of solid, skylit volumes, with shaded passages and open-air courtyards hosting craft demonstrations and workshops. Two additional blocks house residential facilities and a crafts school. Tree-lined grounds provide pockets of shade where visitors can pause and reflect—making LLDC not just one of India’s finest craft museums, but also a living, breathing hub of learning and innovation.

Turtuk, Ladakh: India’s Balti Frontier at the Edge of Siachen

By Tara Sharma

[View of River Shyok near Turtuk Village in Ladakh. Photo by Rajnish71, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Turtuk, tucked into the lap of the rugged yet majestic Karakoram mountains in Ladakh’s Nubra district, is one of only a handful of Balti villages in India. Perched close to the Line of Control, it occupies a place where history, culture, and geopolitics intersect.

Post independence, for decades, the village lay beyond India’s borders, part of Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region. That changed during the 1971 India-Pakistan war, when a young Ladakhi officer, Major Chewang Rinchen, led an audacious operation to capture Turtuk. The victory secured a strategic gateway to the Siachen Glacier, lying just a few kilometres away, and placed the Shyok valley under India’s watch. For his leadership, Rinchen was awarded a second Maha Vir Chakra—an extraordinary feat for a soldier who had first received the honour at just 17, defending Ladakh in the 1947–48 war with Pakistan.

For the next four decades, Turtuk remained largely closed to outsiders. Only in 2010 was it opened to tourists, revealing a place where Balti traditions thrive against a stark Himalayan backdrop. The Siachen Base camp is also now open to tourists.

[Entrance to the Yabgo Palace]

The road to Turtuk traces the magnificent Shyok river, passing remote hamlets before arriving at a tall wooden suspension bridge—the entrance to the village. From there, narrow cobbled lanes shaded by apricot, walnut, and willow trees wind towards its cultural heart: the Yabgo Khar, the residence of the former rulers of Chorbat-Khapulu in Baltistan. Its thick stone walls, timber bracing, and intricately carved wooden arches speak of a bygone era, while its genealogy charts, ceremonial attire, and weaponry offer a window into the region’s storied past.

Beyond the palace, fragments of traditional Balti architecture survive amidst modern cement houses. The Ashoor family’s Balti Heritage House and Museum preserves this legacy—its kitchen displaying heavy stone cooking pots, or doltok, still used in local households. Visitors can also taste Turtuk’s culinary heritage: nutty buckwheat pancakes (kisir) served with mint-scented curd (tsamik), a reminder that the village’s cultural roots run deep into Baltistan’s soil.

Today, Turtuk is more than a scenic stop on a Ladakh itinerary—it is a living reminder of how borders shift, cultures endure, and remote communities become vital to the story of modern India.

Birsa Munda International Hockey Stadium, Odisha: The New Cathedral of Indian Hockey

[Photo by HockeyStadiumRKL - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Some stadiums are worth visiting for the match. This one is worth visiting for the feeling. In Sundargarh’s red-earth country, in the industrial town of Rourkela, the Birsa Munda International Hockey Stadium rises like a silver and green apparition. Here the game is not played for applause alone, but for the pride of a people who live and breathe it.

It is the world’s largest fully seated hockey stadium, with 20,011 bucket seats curving around two FIH-approved turfs, flanked by a gymnasium and a World Cup Village for eight international teams. Built in just 15 months, it already feels as if it has always belonged here.

The name honours Birsa Munda, the tribal hero who defied colonial rule. It is a reminder that progress is real only when it honours its roots. Hockey here is not just a sport; it is part of the air. In 2024, at the 14th Hockey India Senior Men’s National Championship, Odisha triumphed over Haryana with 17 of the 18 players coming from Sundargarh.

When Rourkela co-hosted the 2023 Men’s Hockey World Cup, twenty matches were played here under floodlights. The stands shook with drumbeats and chants. You do not just watch hockey here. You feel it in your chest, in the thunder of the crowd, in the speed of players raised on these very fields.

Since the stadium opened, it has done more than stage matches. It has given the youth of Rourkela and surrounding villages a stage worth dreaming about. Children who once played barefoot on dusty fields now press their faces to the railings, studying the world’s best players up close. Coaches say attendance at local hockey camps has surged. Parents, seeing possibility, are more willing to let their daughters pursue the sport.

You may come for the hockey, but you will leave with something rarer: the sense of standing where India’s sporting heart beats loudest, in a corner of the country that has given more to the game than it has ever asked in return

National Defence Academy, Khadakwasla, Pune: The Long March to Equality — NDA’s First Women Cadets Join the Parade

By Kajal Mehra

[Sudan Block, National Defence Academy, Khadakwasla, Pune. Photo by PRONDA - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

India’s premier tri-service military academy—the first of its kind in the world that trains cadets from all three branches together—has played a vital role in developing the country’s military leadership and defense capabilities. It was commissioned in 1954 and its alumni have gone on to become chiefs of staff and war heroes, and have achieved distinction in fields like sports and space exploration.

On May 30, 2025, the NDA once again marked a key moment in Indian military history when the first batch of women—17 cadets—graduated alongside over 300 male cadets during the 148th Passing Out Parade.

Women have served in the armed forces’ auxiliary services through Short-Service Commission since 1992. And since 2016, as fighter pilots in the Air Force. Now their entry in the NDA, following the landmark 2021 Supreme Court ruling allowing women to apply to the Academy, paves the way for women to train for combat and command roles. This gives them a path to permanent commission from the start.

With this, India joins countries like the USA, Canada, Australia and others to give women an equal opportunity to serve with distinction. It marks another step towards gender parity in the armed forces and in shaping a modern, representative Indian military. 126 women have joined the NDA since the first batch out of hundreds of thousands of aspirants.

There’s no separate quota for women; admission is through the common NDA entrance exam, followed by rigorous physical and medical tests at the Services Selection Board.

Training is gender-neutral—with minimal modifications to the core curriculum. Training methodologies were adapted from sister service academies that already train women: Officers’ Training Academy in Chennai, Indian Naval Academy in Ezhimala, Kerala, Air Force Academy in Dundigal, near Hyderabad.

However, it wasn’t easy for this all-male academy to make this transition. Infrastructure modifications were made for comfort, such as adding separate washrooms. Initially, women cadets had separate accommodations, but as the batch progressed, they were fully integrated into NDA’s 18 squadrons, living and training alongside male cadets in academic, military, leadership, and outdoor activities.

Alongside, a cultural and societal mindshift had to happen. Training officers had to be sensitised in their communication styles. The Academy established dedicated support staff and resources tailored to women cadets, helping ease adaptation and ensuring safety and comfort.

Going forward, based on feedback and observations, the NDA may introduce improvements in instructor training, counselling, mentor programmes, and squadron-level sensitization to better support mixed-gender leadership development. Expansion appears to be incremental, suggesting a walk-before-run approach to scaling numbers while maintaining integration quality.

One can visit the NDA, on the outskirts of Pune, nestled against the backdrop of the Maratha stronghold, the Sinhagad fort. But it requires prior permission and is generally restricted to Sundays for organized groups and individuals. Visits are intended to be motivational. The campus itself has reminders of India’s contribution to military diplomacy. For example, Sudan Block, which commemorates the Indian soldiers' role in the East African Campaign during World War II.

Udupi: From Temple Kitchens to City Streets: Shaping India's Dining Culture

[Sri Krishna Temple, Udupi]

Every day, thousands in India walk into modest restaurants with bare tables, short menus, and no fanfare, places devoted to good, affordable vegetarian food. Few realize they’re part of a tradition that began in the temple kitchens of a small coastal town in Karnataka and went on to shape how India eats.

Udupi’s Sri Krishna Temple, a revered place of pilgrimage for millions, also pioneered one of India’s most successful mass-dining templates. For centuries, devotees there were served free meals of rice, lentils, local vegetables, and coconut—simple food that was clean, nutritious, easy to prepare year-round, and scalable for large numbers. This became a cuisine built on first principles: hygienic, replicable, and accessible.

When people from the Udupi region migrated to cities like Chennai, Bombay, and Bangalore, they carried this model with them. Early pioneers included K. Krishna Rao (Krishna Vilas, Chennai), Maiya family (MTR, Bangalore), and Rama Nayak (Bombay). The formula—limited menus of a dozen consistent items—ensured quality and easy replication. Like McDonald’s decades later, Udupi restaurants proved that simplicity and standardization could drive both good food and good business. Only, in case of Udupi hotels, no one imposed it from the top. The model evolved organically through shared learning.

Adaptations followed. To draw local customers, many added North Indian dishes to South Indian staples. The core culture endured: unfussy interiors, focus on food, and loyal patrons remembered by name years later. Some became supply hubs for Indian groceries and spices, vital to communities abroad. MTR, for example, grew from a Bangalore restaurant into a global packaged-food brand. Staff trained in Udupi establishments started their own ventures, spreading the model well beyond its home region.

By the 1960s and 70s, as Indians migrated to the US, Australia, and the Gulf, the pattern repeated. Udupi-style restaurants abroad served not just as eateries but as community centers. Today, walk into almost any South Indian restaurant worldwide and you’ll see the imprint: simple, well-prepared food, democratic service, efficient operations, and fair prices. The dosa is now as familiar in New York or Sydney as in Bengaluru.

Udupi’s gift to post-Independence India was profoundly practical. At a time of national identity-building, it showed how tradition could evolve to meet modern needs. These restaurants became quiet laboratories for an India that was diverse, welcoming, and accessible. In feeding the nation, Udupi also helped define it.