[Image by Adrian Balea from Pixabay]

Good morning,

Some of us spent the weekend at home fending off questions from our children. How do they come up with these kinds of questions? Some pointers on what we can learn from children lie on the pages of Curious: The Desire to Know and Why Your Future Depends on It by Ian Leslie.

“Paul Harris, a professor of education at Harvard, is an expert on children’s question-asking… he estimates that between the ages of two and five, children ask a total of 40,000 ‘explanatory’ questions. ‘That’s an amazing number,’ he says. ‘It shows that questioning is an incredibly important engine for cognitive development.’ These explanatory questions can be profound or silly, perceptive or incomprehensible, stirring or hilarious. Here’s a random sample of questions from my friends’ children, all of whom were under ten years old when they asked them:

- When I am sixteen will all of you adults be dead?

- What happens if your eyes turn into flies?

- What is time?

- Did you used to be a monkey?

- Why can’t I run away from my shadow?

- If I’m made from a bit of mummy and a bit of daddy then where does the bit that’s me come from?

- Will I die on the cross like Jesus?

“Paul Harris points out that asking a question requires a complex mental process. ‘The child has to first realise that there are things they don’t know… that there are invisible worlds of knowledge they have never visited.’ They also have to realise that other people are information-bearing agents, and that language can be used as ‘a tool for shifting stuff from that person to them’. The question is a technology that children use to trawl for insights… Every question is a little bet. From a very young age, children sense that any information they can gather, even if it doesn’t have an immediate application, may come in useful in the future. Some of their questions will lead to dead ends, confusions or refusals from embarrassed parents. But, cumulatively, their questions bring knowledge, and with more knowledge, the child knows that he is growing, just as surely as he knows he will exceed this year’s chalk mark on the wall chart next year.”

May we submit then: stay curious.

In this issue

- China’s late mover advantage

- The art of leading without being a leader

- Explain yourself

FF Exclusive: China’s late mover advantage

In the second and final part of his essay, G Venkat Raman, Associate Professor, Humanities and Social Sciences at IIM Indore, argues that China's growing tech prowess, access to Big Data, and its expanding digital footprint gives it a strategic advantage. And that in turn will play a decisive role in determining China’s role in international politics and business.

He writes: “At the peak of the Cold War, in 1963, the US federal government spent more on R&D than the rest of the world's public and private sectors combined. This military technology spending later led to industrial applications making the US an unparalleled tech domain leader. Today, the US spends less on R&D proportionate to its GDP than in 1955. China seems to have learned the lessons of history better. For instance, US bans on the export of chips to firms like Huawei and ZTE have led Beijing to invest $29 billion to support the domestic chip industry. Today, the digital platforms and mastery over AI, cloud computing, and robotics appear to be the new sites of power conflicts in the international system. In the age of IoT and AI, China has immensely benefited from what some experts have called the late movers’ advantage. No matter what, China's emergence as a tech power is bound to play a critical role in the years to come.”

Dig Deeper

- Read: Part 1: The US-China war for tech supremacy is splitting the world in two

- Read: Part 2: Should the world be worried about Chinese tech?

- Discuss with G Venkat Raman: Head to our Slack channel

The art of leading without being a leader

In a profile of Muttiah Muralitharan in The Cricket Monthly, Andrew Fidel Fernando talks about the role Murali played in his team during a crucial period of Sri Lankan cricket. For some context before you get to the extract below, Murali came into cricket at a time hierarchy was all important. In another interview (in Tamil), Murali told Ashwin Ravichandran that in those days while cricketers got to stay in 5 star hotels, the allowance they got was so little, that they used to eat outside, and do their own laundry—and hierarchy was so entrenched that the young player had to do the laundry for seniors. Having gone through that phase, Murali wanted to make things easier for his own juniors.

Fernando writes: “Within the team, Murali never officially held a leadership position, captaining zero of his 495 internationals. He has not been, never pretended to be, nor perhaps ever been possessed of the necessary subtlety or calculation to be, a general. What came naturally was to throw himself fully into the kind of bottom-up work the generals needed him to do, without them knowing it needed to be done. In the early and mid-aughts, when a string of captains were intent on breaking down the Ranatunga brand of hierarchy within the dressing room, opening up team meetings to younger players and hectoring the board for more equitable models of payment, it was Murali, the superstar, who was first to rush up to new entrants into the side. ‘He had no ego,’ Sangakkara recalled in a lockdown chat with R Ashwin in May. ‘He always spent his time with the youngsters in the team.’ He'd crack jokes in the back of the bus with younger players, ask them out to dinner, or order for the group and host them in his hotel room. He would ‘build the confidence up of the youngsters, much more than Mahela and I ever did’.”

Dig Deeper

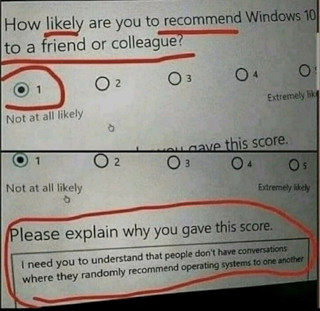

Explain yourself

(Via Pinaki Basu)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy. Head over to our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel