[From Unsplash]

Good morning,

In their book, The Three-Box Solution Playbook, Vijay Govindarajan and Manish Tangri share an interesting story about how IBM once tested a critical assumption about a product they were thinking of developing.

Critical assumptions, Govindarajan and Tangri write, “are those that if proven false have fatal consequences for the project. Either it is game over for the project or the project requires a significant pivot.”

These assumptions have to be tested in the incubation stage itself, which might not have access to large funds. They write, “the golden rule is ‘spend a little, learn a lot.’ You should be able to articulate how, while incurring little cost, you’ll test assumptions—and fail fast if they are invalid.”

One of the most interesting examples they give is that of IBM, which was experimenting on speech-to-text technology. They write, “in the 1980s, IBM wanted to know whether customers would be interested in a system that automatically converted users’ speech to text. Instead of spending a lot of money building a prototype—an expensive proposition in an era when computer processing power wasn’t cheap—and tackling the formidable computer science problem of converting generalized speech to text, IBM conducted a low-cost experiment. The company invited people who were excited about this possibility to a room equipped with a microphone and computer terminal but no keyboard. The subjects were asked to speak into the microphone, and the words automatically appeared on screen. What the subjects didn’t know at the time was that there was no technology in place; there was simply an individual in an adjacent room typing the subjects’ speech. Without this knowledge, the subjects could experience the idea and react as if the system truly existed. IBM discovered that the subjects didn’t respond favourably to the experience, for a variety of reasons. Thus, the company tested a critical assumption quickly and cheaply.”

In this issue

- Camel economics

- Power and the System

- Two Indias

Camel economics

In his recent column in The Indian Express, Rajiv Mehrishi, a former civil servant, Rajasthan cadre, shares some interesting stories about camel economics. Mehrishi takes off from a National Geographic story that pointed out, “that there are fewer than 200,000 camels left among the nine breeds”. The title of NatGeo essay was alarming. It read, “Camels are disappearing in India, threatening a centuries-old nomadic culture”.

Mehrishi highlights some of the reasons. He writes, “the economic benefits of rearing a camel have all but disappeared. Rarely used for ploughing, as a draught animal, the camel was largely a means of transportation for goods and people. The road network in Rajasthan has grown by almost 30 times since 1951, slowly but surely eliminating the need for the ‘ship of the desert’. Camels, or camel carts carrying people or goods—so common even a few decades ago—can rarely be seen now. Till the 1960s, IAS/IPS officers routinely toured their districts on camels; today, not one is likely to be able to ride a camel even across a parade ground.

“In fact, the effort made by the Government of Rajasthan—enacting The Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015—has had just the opposite effect. Forced by economic reality, the Raika sold their camels to any buyer, including those who they suspected of buying it for meat, in great demand in the Middle East. The ban on camel slaughter, or sale of camels for slaughter, did what such bans usually do: They simply drove the sale-purchase to the grey market, driving down camel prices.”

Dig deeper

- Camels are disappearing in India, threatening a centuries-old nomadic culture - National Geographic

- Decline in India’s camel population is worrying - The Indian Express

Power and the system

Brian Klass is a researcher at the University College, London and author of Corruptible: Who Gets Power and How It Changes Us. His essay in Foreign Policy that does a deep dive into why regular people break rules, bankers misbehave, and bees mate, got us thinking because he asks an interesting question: Does the system that people live in corrupt them?

Talking about bees, he points out, “Being the queen is a sweet gig. You have an entire hive devoted to you, and you get to reproduce your genetic material with gleeful abandon. In the evolutionary sweepstakes, the queen bee has won the lottery. Her genes are passed along to every bee or wasp in the hive.

“But worker bees and wasps have a hidden instinct: They want to pass their genes along, too. We won’t go into the complicated math equations here, but dramatic evolutionary competitions are going on inside a hive. These competitions pit what is best for each individual against what is best for the hive.

“All female larvae can become queens with the right diet. Give them the right baby food, and it’s straight to the honeycomb version of Buckingham Palace. For each larva, then, becoming the queen bee is the ideal evolutionary outcome. But from the perspective of the hive, any excess queens are a waste. Queens can’t carry out tasks that are normally assigned to workers…

“But, as is the case with humans, the wasps doing the policing sometimes abuse their authority for their own gain… So here’s the interesting question: What causes some bee or wasp species to have more or less corrupt, opportunistic behaviour compared to other species? Are they the selfish jerks of the social insect world?”

The answer lies with the system, not the individual.

Dig deeper

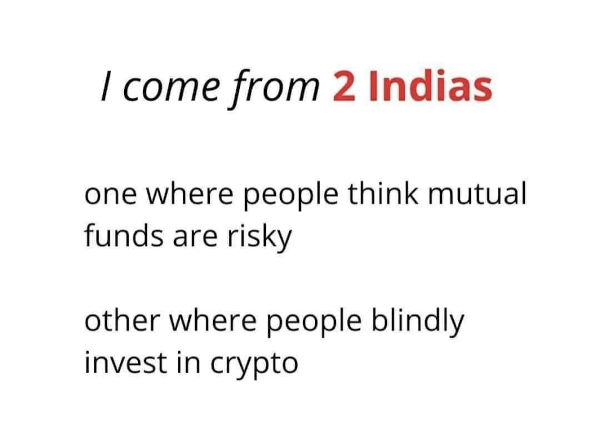

Two Indias

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)