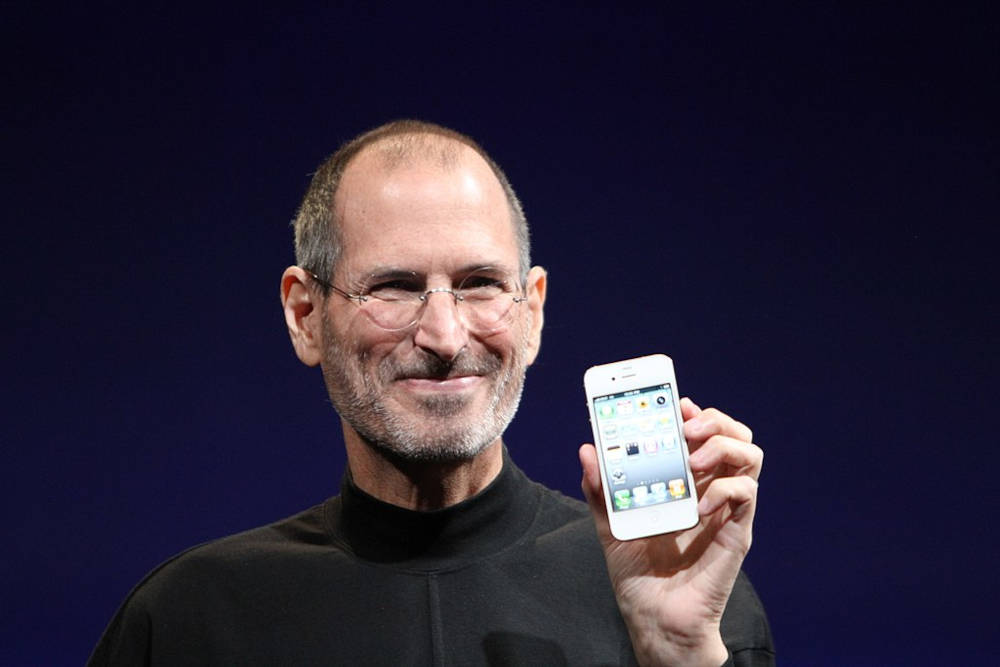

[By Matthew Yohe at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Dear friend,

Towards the end of his biography of Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson deviates from the tradition of having the last word about his subject and gives that space to Jobs’s own thoughts on what he hoped his legacy would be.

His reflections are relevant today when it’s so common for entrepreneurs to found companies with the sole aim of selling them off. Steve Jobs says:

“I hate it when people call themselves ‘entrepreneurs’ when what they’re really trying to do is launch a startup and then sell or go public, so they can cash in and move on. They’re unwilling to do the work it takes to build a real company, which is the hardest work in business. That’s how you really make a contribution and add to the legacy of those who went before. You build a company that will still stand for something a generation or two from now. That’s what Walt Disney did, and Hewlett and Packard, and the people who built Intel. They created a company to last, not just to make money. That’s what I want Apple to be.”

Apple has done two things very well: Build products that scored high on functionality and aesthetics and sell them to customers. A piece of career advice from Naval Ravikant might well have been Apple’s playbook. Ravikant said: “Learn to sell. Learn to build. If you can do both, you will be unstoppable.”

However, Jobs himself placed a premium on building rather than selling. In Isaacson’s book, Jobs says this: “I have my own theory about why decline happens at companies like IBM or Microsoft. The company does a great job, innovates and becomes a monopoly or close to it in some field, and then the quality of the product becomes less important. The company starts valuing the great salesmen, because they’re the ones who can move the needle on revenues, not the product engineers and designers. So the salespeople end up running the company. John Akers at IBM was a smart, eloquent, fantastic salesperson, but he didn’t know anything about product. The same thing happened at Xerox. When the sales guys run the company, the product guys don’t matter so much, and a lot of them just turn off. It happened at Apple when Sculley came in, which was my fault, and it happened when Ballmer took over at Microsoft. Apple was lucky and it rebounded, but I don’t think anything will change at Microsoft as long as Ballmer is running it.”

Looking back, Jobs was right. Microsoft’s fortunes picked up when Ballmer stepped down, and gave his place to a hardcore engineer, Satya Nadella.

Apple’s fortunes have grown even bigger under an operations guy Tim Cook. But there are some who believe that it came at the cost of Steve Jobs’s own legacy. A forthcoming book by Tripp Mickle has the title “After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul”.

The danger of a single story

In The New York Times, Molly Worthen, a historian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, writes about how MBA education has changed in recent years. One example of that change is in the evolution of case studies.

She writes:

“Here is the central tension of modern business education: At a time when society needs managers who can grapple with uncertainty and operate in a culture divided over basic questions of justice and human flourishing, most business schools still emphasise specialised skills and quantitative methods, the seductive simplicity of economic and social scientific models. They often reduce the weirdness of human organisations to the tidy pedagogy of the case method, in which students discuss 15- to 20-page accounts of how an individual or a corporation handled some task or crisis.

“‘The case method is theatre,’ Mr. [Roger] Martin [the former dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, and author of When More Is Not Better.] said. ‘There’s a case, and then there’s a teaching note that says what the point of the case is. Some notes will be as specific as to say: ‘ask the following question, wait till you get this answer, then write that out on the board.’ It’s no different from Shakespeare—people have lines, there’s multiple acts, everyone plays their role, and you know the answer ahead of time…’

“Now, there is change.

“Yet the writing and teaching of cases has become more nuanced in recent years, partly in response to the focus on environmental and social impact. ‘We do this nice thing where in each case, you map out all the stakeholders in the process,’ Cynthia Madu, who is about to graduate from the Tuck School at Dartmouth, told me. ‘It lets us identify all the people actually there, so we don’t think it’s the C.E.O. doing everything. Also, if students know there’s not one single narrative, they’re more willing to debate in class whether it’s the correct narrative.’”

Dig deeper

- This is not your grandfather’s M.B.A.

- The danger of a single story - Chimamanda Adichie

The trouble with Congress

In The Telegraph, Sankarshan Thakur argues that the Congress party itself is mainly responsible for its own decline, and that decline is bad for the country.

He writes: “Since it lost power in 2014, the Congress has slalomed in an astonishing fashion. If there could be an aspect of the Congress more astonishing, it is that it doesn’t appear bothered with, or even sensed of, the depths of its plunge. The few signs of recovery it revealed, it frittered—the victories in Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan have either become things of the past or are well on their way there. Kamal Nath, for all his fabled backroom heft, could not prevent his swift sundering by the Bharatiya Janata Party. Amarinder Singh was toppled by his own and replaced by factional rivals so taken by their ambitions and so riven that they were never going to measure up. Sachin Pilot is an asset allowed to turn ruefully sore in Rajasthan. T.S. Singh Deo of Chhattisgarh is similarly aggrieved. It isn’t hard, or fanciful, to foresee the Congress smoked wholly out of power; it shan’t be unfair then to argue that the Congress contributed most to the establishment of a Congress-mukt Bharat.”

He concludes: “The Congress and Rahul Gandhi are, of course, entitled to run their affairs as they wish to and, on the evidence of an inexcusable length of wasted time, run the enterprise aground. What they are not nearly as entitled to as the nation’s oldest political enterprise is to offer neither harbour nor hope to the majority of votaries who still do not subscribe to Narendra Modi’s model of the destruction of the idea of India. That’s the heinous dereliction the court that rules the Congress is really guilty of.”

Dig deeper

Quality vs. price

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel