Good morning,

Why do some people demonstrate fair behaviour and others unfair behaviour? This is a theme Michael Gazzaniga explores on the pages of Who's in Charge? Free Will and the Science of the Brain. To do that, he goes through the nuances of happiness and how various cultures perceive it. He does a deep dive into a study by the researcher Richard Nisbett and his colleagues.

“One definition of happiness for the Greeks was that it consisted of being able to exercise their powers in pursuit of excellence in a life free from constraints. Ancient Chinese differed in that their focus was on social obligation or collective agency. ‘The Chinese counterpart to Greek agency was harmony. Every Chinese was first and foremost a member of a collective, or rather of several collectives—the clan, the village, and especially the family. The individual was not, as for the Greeks, an encapsulated unit who maintained a unique identity across social settings.’ With harmony as the goal, confrontation and debate were discouraged.

“Nisbett and colleagues suggest that social organisation affects cognitive processes indirectly by focusing our attention on different parts of the environment and directly by making some social communication patterns more acceptable than others. The idea is if one sees oneself as an interwoven part of a big picture, then one might look at all aspects of the world holistically, whereas if one sees oneself as having individual power, one looks at aspects of the world individually. And that is what has been demonstrated. In tests where Americans or East Asians described simple scenes that were flashed to them and later were tested on what they remembered from the scenes, Americans focused on the main items in a picture, whereas Asian viewers attend to the entire scene. Is this cultural difference evident in brain function?

“It seems to be. At MIT, researchers Trey Hedden and John Gabrieli had East Asians and Americans make quick perceptual judgments while having an fMRI scan. They were shown a series of differently sized squares and each square had a single line drawn inside of it. The Americans, judging whether the line-to-square-size proportion was the same or different from one square to the next (a relative judgement), showed much more brain activity was needed for sustained attention than when judging if lines were of the same length regardless of the surrounding squares (an absolute judgement of individual objects). For them, absolute judgments about individuals required less work by the brain, but judgments about relationships used more. The exact opposite was true for the East Asians.”

Gazzaniga goes on to explain that “On the neurophysiological level, we are born with a sense of fairness and some other moral intuitions. These intuitions contribute to our moral judgments on the behavioural level, and, higher up the chain, our moral judgments contribute to the moral and legal laws we construct for our societies.”

Interesting!

Editor’s note: We are taking a break for FF Life, our weekend edition, this Saturday. We’ll be back with a fresh edition of FF Insights on Monday, August 29.

Adani - NDTV saga: An update

In a disclosure to BSE on Thursday morning, RRPR pointed out that a SEBI order of November 27, 2020, restrained the two founders Radhika and Prannoy Roy from dealing in securities for two years.

Simply put, the Roys have bought extra time to review their strategic options. Any delay till November 26 means that the Adanis will not be in a position to immediately start the open offer and mount a possible takeover.

But the big question is: what will the Roys finally do on November 27, after the SEBI ban ends?

Read the key update to Indrajit Gupta’s story on Adani’s attempts to takeover NDTV.

Dig deeper

Gautam Adani’s midnight raid at NDTV

Why hybrid work must continue

We’re firm believers that the pandemic exposed us to an altogether different way of working. What is now needed are ways to fine-tune it. But those in the boards and in senior management don’t get it. This explains the great exodus of middle management and Julia Herbst places it in perspective in Fast Company.

“The great remote work experiment that office workers embarked upon in March 2020 has, by and large, been a success. In the summer of 2020, 94% of the nearly 800 employers surveyed by HR consulting firm Mercer reported that productivity rates had stayed the same or improved since employees had started working remotely. More recent studies suggest that employee productivity at home is even higher as people have adjusted to remote practices and procedures. It’s unsurprising, then, that many aren’t eager to return to their commutes, distracting coworkers, and $14 sad desk salads.

“Many leaders, however, feel differently. They have resorted to bribing, cajoling, or—in the case of Elon Musk—threatening to fire employees who resist returning to the office full time. Musk is not alone: Employees generally say they want more flexibility, but an April 2022 survey from employee screening company GoodHire suggests that 80% of senior-level managers think that there should be ‘severe consequences,’ including pay cuts and termination, for employees who don’t want to return to the office.

“That puts managers in the awkward position of trying to implement unpopular policies while they are also overseeing complex working arrangements. Some companies have enacted full return-to-office plans, or waffled back and forth, as Covid-19 surges waxed and waned. Plenty have gone hybrid. (And, yes, a few have made the shift to fully remote and asynchronous.) Each arrangement presents unique challenges for managers, including communicating and enforcing new expectations, and—especially in the case of full-time return-to-office plans—navigating employee pushback and subsequent departures.

“Some managers are responding by simply throwing in the towel. When Apple announced plans this past spring to compel workers to clock in to its Cupertino headquarters at least three days a week, a group of employees published an open letter protesting the demand. Soon after, the company’s then director of machine learning, Ian Goodfellow, quit, reportedly telling his team that ‘more flexibility would have been the best policy’ for them. After Goodfellow accepted a job at Google, Apple walked back its in-person strategy.

“It also doesn’t help that managers operating in these hybrid environments often don’t have the proper training to evaluate employees’ performance, says Brian Elliott, a senior VP at Slack who is also executive leader of Future Forum, a future-of-work think tank launched by the Salesforce-owned workplace messaging platform. Managers have traditionally been taught to measure someone’s hours spent on a task, rather than outcomes, which are the essential metric in a remote, digital-first environment.”

Dig deeper

This is why no one wants to be a middle manager anymore

Measure the harm

In MIT Technology Review Nathaniel Lubin and Thomas Krendl Gilbert, researchers at Cornell Tech, argue that tech companies that use methods such as randomised trials to measure engagement can use the same approach to measure harm during the product development process. It would then make it easy to limit the harm they cause downstream.

They write: “Structural problems are direct outcomes of product choices. Product managers at technology companies like Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok are incentivised to focus overwhelmingly on maximising time and engagement on the platforms. And experimentation is still very much alive there: almost every product change is deployed to small test audiences via randomised controlled trials. To assess progress, companies implement rigorous management processes to foster their central missions (known as Objectives and Key Results, or OKRs), even using these outcomes to determine bonuses and promotions. The responsibility for addressing the consequences of product decisions is often placed on other teams that are usually downstream and have less authority to address root causes. Those teams are generally capable of responding to acute harms—but often cannot address problems caused by the products themselves.

“With attention and focus, this same product development structure could be turned to the question of societal harms... Companies could implement protocols themselves, but their financial interests too often run counter to meaningful limitations on product development and growth. That reality is a standard case for regulation that operates on behalf of the public. Whether through a new legal mandate from the Federal Trade Commission or harm mitigation guidelines from a new governmental agency, the regulator’s job would be to work with technology companies’ product development teams to design implementable protocols measurable during the course of product development to assess meaningful signals of harm.

“That approach may sound cumbersome, but adding these types of protocols should be straightforward for the largest companies (the only ones to which regulation should apply), because they have already built randomised controlled trials into their development process to measure their efficacy.”

Dig deeper

Social media is polluting society. Moderation alone won’t fix the problem

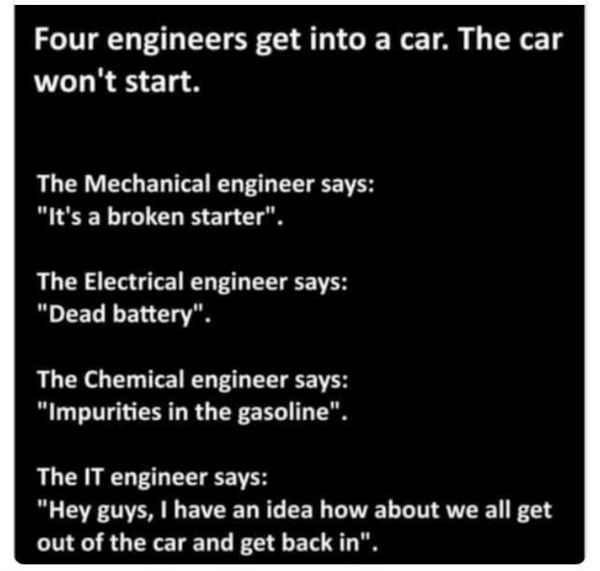

Engineer-ed

(Via WhatsApp)

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel