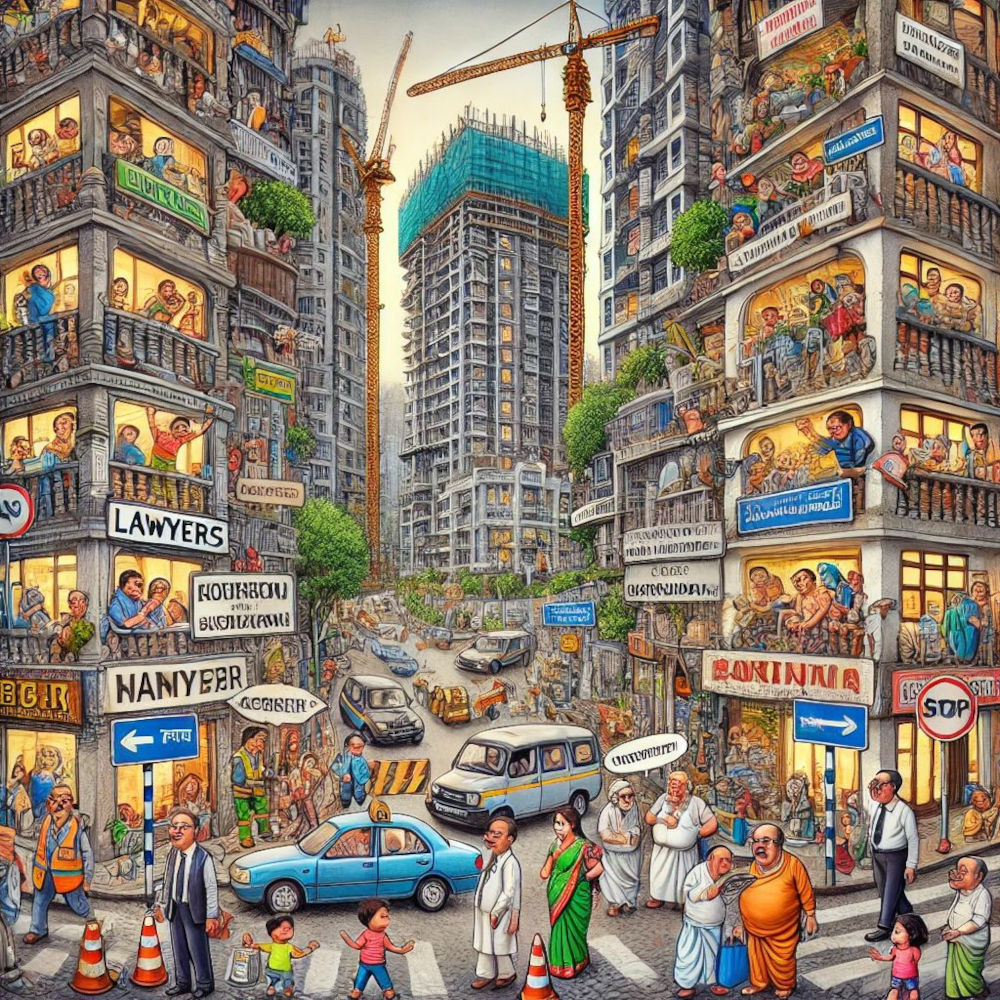

[Image generated by ChatGPT]

I live at an apartment complex in Mumbai that is over 35 years old now. Like many others in the city, I am actively at work to redevelop the property I live in. This is the only reason why I decided to participate in the elections to be a part of the Managing Committee (MC). I imagined from the outside that as a person with ‘fresh ideas’, I will be able to move the redevelopment agenda faster. I was wrong. Horribly wrong. The import of what my friend Dr Rahul Chavan, secretary of the Housing Society, said, started to sink in: “I haven’t studied as hard after I completed my MD.” I’ve had much to learn over the last few months.

Leading a redevelopment project isn’t as easy as razing an existing building and creating a new structure. My first brush with the complexities was that there are disgruntled elements who covet the position you have been elected to. By now, I’ve gotten used to questions such as “What’s in it for you, eh?” It’s a thorny way of asking that as a member of the MC, a pro bono position, will I wrangle some deal for myself from a developer.

This is not to suggest all MCs are clean. Or for that matter that officials in government are totally transparent. Over the months, my conversations have shown that the cost of redeveloping a building in Mumbai escalates by Rs 200-500 per square feet on the back of bribes paid to people in key positions to secure all permissions.

If this is such a pain, why go in for redevelopment? Like I said earlier, I live in a complex that is over 35 years old. Water seeps through the walls during the monsoon. The pipes have gone all rusty. The electrical fittings are worn out. I can go on and on. The incentive then to have a new structure with contemporary amenities and that will last another 50 years is high.

Then there are financial and other incentives as well. When a new structure is built, the maintenance charges go up. But I am a witness to negotiations where each resident gets a corpus that stays invested in a sinking fund. The interest on this corpus pays for the higher outgoings. The longer term outcome is that I emerge better off financially. And over the years, the white goods such as the refrigerator, television and airconditioners get old. The developer is committed to providing new apartments with brand new white goods fitted in. I don’t see any reason why not to go for the deal.

There’s a financial upside to this as well. In any suburb, there is a premium on a newer apartment as opposed to an apartment of the same size in an older building. When redevelopment is done right, this gap closes completely. In fact, my conversations have it that there are many neighbours who want the complex to be redeveloped so they can sell their apartment at a higher price and move to an altogether new city with enough money left to retire.

It is from here that the questions begin:

How do you choose a developer? Aren’t they monsters?

Sujay Kalele, founder at Tru Realty, disagrees. His is a technology-driven real estate company that works with all the key players in the real estate ecosystem to create transparency. Kalele, CEO of Kohlte Patil Developers in an earlier avatar, makes the case that as recently as five years ago, developers were seen as people who renege on deals and delay projects indefinitely. But the lay of the land has changed since then as the business models have evolved. Acquiring new land banks is expensive in cities such as Mumbai. And there is regulatory pressure to complete projects on time. It is inevitable then that the days of developers as monsters are behind us. “It doesn’t make financial sense for a developer to delay a project. We incur losses if we do,” he points out. This is a view Kapil Bakshi, founder of Kapil S Bakshi Project Management Consultants (PMC), endorses. (The MC I am a member of is working with him.) Bakshi has worked on D-Mart, Magnet and many other complexes across Mumbai and in other parts of the country.

Developers want to start quickly. If they delay the project, no one knows what's going to happen to the market after one or two years. So they look for projects which take off very fast and go off smoothly. So no, they’re not the monsters they’re made out to be.

What really goes into selecting a developer?

Between Bakshi and Dr Chavan, I have learnt much.

1. The first thing members of a housing society must look at when scouting for a developer is credentials. It is easy to grab the highest offer on hand. But this is like walking into a trap. Anything can happen to a project and it can get stuck. In the past, developers who used to make the highest offer got the bid. And this is how most societies functioned. If the project got stuck or delayed, there are chances a developer even stops paying the rent. These are the monies that are agreed upon between a developer and residents when they vacate their old property until the time a new structure comes up. While some may have a second home, there will be many who don’t have one. In any case, everyone takes this money as compensation.

Delays can happen for various reasons that include question marks on the feasibility of the project that becomes apparent after some time. Perhaps the economic environment may change; or something else, absolutely anything, can happen.

This is why examining a developer’s track record matters . How much time has a developer taken to complete projects in the past? If a developer commits to a project and commits to, say 36 months, have they stuck to that deadline? Or have they gone on to take five to six years? To do this, go back to the developer’s earlier projects and check their history.

One of the most crucial things here is to ask the developer to provide crucial records such as Competition Certification (CC) and Occupation Certificate (CC) for at least three to five of their projects, depending on the size of project for work done over the last five-seven years. In Mumbai, there are many people who live in properties that do not possess these certificates. Without that, everything becomes difficult. For example, the Municipal Corporation may decline to supply water and people may have to depend on water tankers. Occupying properties without such documents can mean selling the property at a later date can be an issue because buyers may not want it.

2. The second is timely payment of rents by the developer. When people stay in their own houses, this is something they don’t have to bother about. All expenses are budgeted for. But when redevelopment begins, there is a shift in everything. People now move to rented premises.

If rent stops or the developer’s cheque bounces, members will have to pay. This is a burden not everyone can handle. The moot point here is to examine closely how a developer you have chosen to work with behaved when they signed earlier agreements. Examine it closely. Talk to other building complexes that have worked with the developer.

Another landmark to look at is the developer’s behaviour during Covid. Bakshi says he has seen many developers declaring that since Covid was a pandemic, force majeure clauses kicked in. This is legalese for an unforeseen or unavoidable event that prevents one party from fulfilling their contractual obligations. Here, the pandemic meant they didn’t have to pay. This can break the back of someone living in a rented place.

3. And finally, the quality of the finished building and the carpet area a developer delivers on. This, Bakshi says, is because you’re going to stay there and you want a good place. So, it is one thing for a developer to complete a project in 36 months. But how well have they done it? You don’t want issues like leakages, bad tiling, cracks and other such problems later. To check for that, visit other projects the developer has completed and talk to the members there.

Nothing, he cautions, is foolproof. There could be some niggles. But if the developer responds and is willing to rectify it, go with them.

It was inevitable then I ask what does a developer look for when considering a project?

Three things, says Bakshi:

1. When a developer takes on a project, they try to figure out if it makes financial sense. It ought to earn profits after factoring in for all the interest costs they pay, escalation in project costs and any other contingencies they must provide for.

2. Some projects may be financially good, but the location may be weak; or the plot size may not be sufficient or good enough for certain developers. By way of example, if a certain project falls in a flight path around an airport, height restrictions kick in and the Floor Space Index (FSI) restrictions kick in. Corporate developers and big developers will not get into a small project of 1,000 square metres and 2,000 square metres. It is essentially the local developers who work within these areas.

3. And finally, they look at how united the members are in a complex. If there are too many non-consenting members, no developer will be interested. Who wants to spend time going to court and getting members evicted? While it is inevitable that there may be some who are against it, if the majority is wafer thin, developers stay away.

To place that in perspective, in theory, the majority to get redevelopment going in Mumbai is 51%. But developers want at least 75%. This is because assuming it’s a small society with just 10-12 members, a 51% margin is too little—that means six members. Even if one member changes their mind, there will be no majority.

So, while they don’t talk about it officially, no developer likes to get into litigation to vacate the building. After all, it’s the market they’re dealing with. No one knows what's going to happen in the market after one or two years.

An argument I’ve heard often is that self-redevelopment is better than going to a developer. Does that stand scrutiny with the experts?

Apparently not! I was surprised. So, I listened carefully to what Bakshi had to say. In redevelopment, there is redevelopment by a developer. And then there is redevelopment by a society—this is self-redevelopment. Essentially it's going to be the same. Whatever costs the municipal corporation (the BMC in Mumbai) charges on premiums and expenses, are the same in either case. By way of example, additional premiums for increased floor space more than what is permitted, and charges for providing access to roads, water, electricity, etc.

There may be certain concessions that were there for self-redevelopment such as nominal stamp duties, registration fees and faster clearances. But they haven’t kicked in yet. And there’s no taking away from all the other expenses because you will want the same cement, finishing material and all else. So, where does the difference come in?

On paper, when it comes to self-redevelopment, it is a project by the society, for the society. So, members will be strict about the quality and will ensure only the best is used. And as theories go, a developer has profits to look at and may cut corners.

But the issues begin to kick in when it comes to financing. That’s a huge challenge and most people are not used to dealing with how to raise it. Do society members chip in? If they do, how much can they do? Will a bank come in? For a project which is very small, say in the region of 1,000 square metres, getting finance from a bank could be possible. But for larger projects, it gets tougher. Banks need some kind of collateral and the only asset a housing society has is the plot they own. This fact hits housing societies hard and members find it tough to navigate. But developers find dealing with it easier because they have access to funds. This is because as a corporate body, it is possible to borrow from the markets like any other corporate would.

What about dealing with senior citizens and others who have genuine reasons to feel worried?

This is a fair question. What I have seen over the last few months is that while there are people who want to torpedo a project, there are those who are petrified of moving out of where they live. Senior citizens are one category. Then there are those who are wedded to the society they live in and don’t want to move out. There are yet others who are financially not stable and are concerned.

Dealing with those who want to torpedo a project is one thing—that needs an iron hand which means a strong MC led by an equally strong-willed leader. As for seniors and the others, what I am a witness to until now is that they are afraid of uncertainty—especially the higher maintenance charges and losing their community. So, when they are kept in the loop on what’s going on through informal conversations and special general meetings (SGMs) on every agenda, they begin to gain a sense of confidence. But this is not just an appeal to their hearts. Developers are willing to work out agreements to move people en masse to another place. It allows them to negotiate cheaper rentals on the one hand while the people don’t lose their sense of community. This works in the interest of both parties.

The transparency also shows people that at the end of this journey, either their lives, or those of who will inherit their property will be better—that’s a big hook and goes a long way to build consensus. I am witnessing this first hand. Those with children and grandchildren whom they want to bequeath their property to, are open to the idea. Then there are those who live alone and have no one to leave it to. They worry about what the future holds. Some have articulated their reluctance to leave and maintain the status quo; and yet others have described concern about what may happen if they cannot come back to the place they have called home for all these years.

One of the biggest learnings I am beginning to appreciate is that there are times you just shut up and listen when people are afraid. Do not offer advice. Sometimes, people just want to talk and be heard without being judged. On doing that, they ask whether the ‘temporary places’ being spoken of will offer them comfort and succour that their now familiar community offers. They need to be reassured it will. Then there are those who wonder if it may be possible to leave their properties to a philanthropy of their choice. When an affirmative answer is offered, they want to know how. And then there are those with whom nothing works. But one step at a time, I tell myself.

Is this an exclusively Mumbai story?

Right now, it looks like that. However, Bakshi doesn’t think so. He asks that property be thought of as an asset and there are people who are thinking of how it can be monetized. What is happening in Mumbai right now is because there are more co-operative housing societies in the city than any place in the country. The idea of redevelopment is just about catching on in other parts of the country.

To make his case, he points to Noida and Bengaluru at two extremes where he is at work on the redevelopment of single homes on plots of land. This is because people see merit in it. To do that, they sign a Joint Developer Agreement (JDA) with a builder in return for a certain number of apartments. The developer sells the other apartments and makes a profit. The original owners get a new structure to live in and can choose to do whatever they want to do with the number of apartments they gain. Incidentally, this has caught the attention of Mumbaikars as well who live in suburbs such as Juhu and Vile Parle and who own bungalows on plots of land. They are now signing up with developers to make apartment blocks there.