[NH 50. Clouds above, the highway ahead—phir se udd chala. Just after a right turn from Chitradurga, Karnataka.]

You could drive a thousand kilometres across India and never notice them. They work in the shadows of the highway glare, surfacing only when someone truly needs them—an invisible guild that keeps the country’s traffic flowing when satellites shrug. My first glimpse of this underground ecosystem was a stroke of luck: I had merely announced a Mumbai-to-Kochi solo run when two names—Vikram Varma (a.k.a Ricky) and Madhu—materialised in my messages, offering to track my journey like silent air-traffic controllers.

It turns out the pair are just the visible edge of a far wider brotherhood: truckers who double as human sensors, dhaba owners who double as live data feeds, and veteran road-warriors who relay updates across the subcontinent in real time. Madhu and Vikram might headline this narrative, but they stand in for hundreds who keep their counsel and their coordinates off the grid. What follows, then, is not merely an account of two resourceful friends—it is a window into the quiet, distributed network that rescues travellers when GPS directions implode.

Ricky, a seasoned driver and longtime friend, didn’t hesitate when I told him of my plans. “Share your live location,” he said. “With me and Madhu.”

[Ricky has sparked a new chapter for his father—late 70s, former IAF and Air India pilot—by introducing him to the quiet thrill of long-distance driving. From cockpits to highways, the journey continues]

I’d met Madhu only once — a soft-spoken mathematics teacher from Bengaluru. I didn’t know then that he also tracked road conditions across India in real time, and advised a small and quiet network of long-distance drivers on how to navigate them.

At first, it felt excessive. Why would two men, hundreds of kilometres away, need to monitor my every move? I would find out soon enough — not in the steady rhythm of kilometres logged, but in the sudden, sharp turns where Google Maps failed, and human intelligence stepped in.

Beyond the Digital Line

The turn came, as digital cartography often dictates, precisely where it shouldn’t have. Six and a half hours into the drive from where I live in Mumbai, Sholapur was on the horizon. Its marker on the screen was a beacon of progress. All indicators suggested it was an hour away. That is when Google Maps, in its infinite wisdom, suggested a sharp left. It meant I leave National Highway (NH-48) on which I was cruising along.

But the map promised a "shorter route." Before any interjection from my remote command centre that included Madhu and Vikram, I complied with what the maps suggested. Instinct, or perhaps the arrogance of self-reliance, decided to ignore the nagging pre-departure warnings. “When in doubt, call us. Don’t do anything stupid!”

[Sunset spills across the fields as you cruise past Solapur—where the sky lingers a little longer, and time seems to slow down]

It wouldn’t be too long before the reassuring tarmac dissolved. Soon, I could feel a ribbon of broken asphalt, flanked by scrubland that grew increasingly dense. And for as long as the eyes could see, a dirt track appeared. While my car is a hybrid, I thought I could hear it protest on paths cows and goats would otherwise appreciate. The brutal sun overhead seemed to mock my escalating isolation. Clearly, I was in the middle of nowhere. I’d later learn, 30 kilometres away from anything resembling a main road.

Then, the phone rang. Madhu. His voice, remarkably calm, cut through the anxiety in the cabin. No recriminations. No audible panic. He started with a question: “What do you see around?”

I described what I could.

What followed were a sequence of precise commands: “Go straight for five kilometres. Turn left now. On for 500 meters. Straight, then right at 350 meters."

Each instruction was delivered with the quiet confidence of a man dictating from an aerial perspective. It felt counter-intuitive, yet absolute. I followed. The landscape remained desolate, the track unwavering. Doubt, a persistent presence, kept whispering. And then, as if by some magic, the main road materialized. I merged onto it.

The episode in Sholapur was a stark re-education. My own history with the open road, stretching back to a battered Maruti 800 driven by three friends in their first jobs from Delhi to what was then-Bombay. It had instilled a particular understanding of adventure.

Pit stops included an iconic Taj Mahal, a village whose name is lost to time, and a persistent question mark over the car’s structural integrity. Much water has passed under that bridge. One of those friends, a mind of razor-sharp intellect, passed before COVID. Another moved to Singapore. I am here, writing this.

My first car, another Maruti 800, later propelled me from Mumbai to Kochi and back, hugging the Konkan coastline. That was a journey of pure scenic discovery. These were trips defined by freedom, by the absence of external monitoring. But India’s roads, like its economy, had been in constant, accelerating flux. My immediate observation, after clearing Pune, was how dramatically the infrastructure had evolved. Long stretches of pristine four-lane highways now stitched the country together.

The instinct, a primal urge for any driver, was to floor the pedal. But again, the remote command centre had issued its pre-emptive strikes. Warnings about ubiquitous cameras and impending fines had been relayed. I, of course, chose to learn the hard way. A phone pinged. A 2,000-rupee speeding ticket. My sheepish compliance with the speed markers that followed was immediate and uncharacteristic. The omnipresent gaze, it seemed, was already active.

The comfort that settled in, in knowing Madhu and Ricky were monitoring my progress, was a subtle, almost imperceptible shift. It was a confidence not born of blind trust, but of accumulating data points: the precise prediction of a speeding ticket, the impossible navigation out of Sholapur. This was a system that functioned. But how? My initial query on the logistical feasibility of their remote oversight now demanded a deeper inquiry.

What emerged was something interesting.

The Human Algorithm: Data Beyond Satellites

My conversation with Madhu after getting back to Mumbai deconstructed the mystery. It revealed a nuanced understanding of cartography. His explanations, delivered with the precision of a seasoned cartographer and the pragmatic wisdom of a field operative, revealed a system born of relentless personal engagement.

"When I look into the map," he’d explained, "I first put on a traffic mode. And I see all the traffic. Let's say you are traveling on NH48 and Google Maps indicates a stretch with red light. Then I’ll check the other roads also." But as he would tell me, this isn’t merely about observing a static screen. This was dynamic interpretation, a reading of patterns that the uninitiated might miss. Google Maps, he pointed out, updates every two minutes. But its algorithm is blind to nuance.

It defaults to the "shortest route," indifferent to whether that path is a smooth four-lane, a single-lane potholed nightmare, or a village track where laundry dries on the asphalt. It measures only the absence of vehicles, not the quality of the passage. The "shorter route," especially when state highways cut through towns while national highways bypasses them, often proves to be the most inconvenient and time-consuming for a car. Madhu's method involves watching traffic patterns for five to six minutes, identifying potential detours before entering a jam, and considering factors beyond mere distance, factoring in decades of personal road reconnaissance.

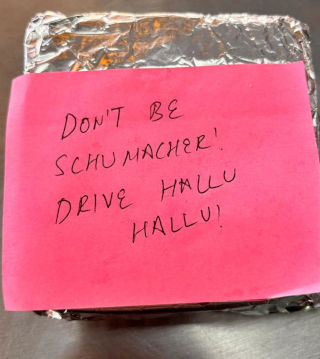

[Tucked into the sandwich bag, a yellow post-it from his wife Anita—her way of saying: “Drive safe, Ricky.” A quiet ritual before every road trip.]

His insights aren't just derived from observing a screen, however. They are the synthesis of decades of direct, on-the-ground intelligence gathering. "Because of my vast travel experience," he stated, "I make it a point that I take down the number of someone whom I build a rapport with on the ground.” This is why over the 12-15 years that he has been driving across India, he has friends with dhaba owners, truck drivers, local pan beedi vendors, and all other assorted kinds who keep a watch on what’s happening around.

It took a while for me to let it sink in that he has built a granular, hyper-local network that can be activated on demand. A call to a friend in Gujarat, Assam, or Kerala can yield real-time, ground-level intelligence that no satellite or digital crowd-sourcing can fully provide. For instance, how does the humble beedi shop owner, perched by a highway dhaba offer critical information?

[In Satara, the vada pav and misal pav come piping hot and full of soul. It’s a ritual stop for Ricky and his dad—fuel for the road, and a taste of home.]

He recounted an instance where a Google Map showed a red zone, indicating a jam. But on calling a local contact, it revealed that it was merely seven or eight trucks parked together for a meal. "When the vehicles are parked, you don't switch off your Google Map or location. So the Maps algorithm indicates the place is having a traffic jam."

It’s an elegant, almost subversive, workaround to technological blind spots, an acknowledgment that human observation still trumps machine logic in certain contexts.

The Crucible of Experience: Madhu's Lived Data

Madhu’s system isn’t stitched together from theory or speculation. It’s built on experience, often uncomfortable and sometimes downright risky. “I like to experience the good, the bad, and the very bad,” he told me, with the calm detachment of a field researcher.

He travels 60 to 80 days a year by road. It isn’t just leisure. It’s reconnaissance as well–not for anything else, but because people such as him are passionate about it. He notes road quality, weather patterns, seasonal bottlenecks. He records everything, mentally and sometimes manually. What I once mistook for a photographic memory was simply the output of long, careful accumulation.

His journeys stay within South Asia—Bhutan, Nepal, Burma—but his focus is India. That geographical constraint is what gives his data its unusual depth. Madhu is not a generalist. He knows India’s roads like a geologist knows rock layers.

[Aizawl city—at first glance, it looked like a snow-capped mountain. From a distance, the mist and clustered rooftops blur into something almost alpine.]

He recalled one such expedition to Mizoram. A friend had warned him: “Don’t go. The local vibes are very hard.” But he wanted to see for himself. What he experienced there still disturbs him. “Locals asked me, very directly, why someone from South India was ‘coming here from India,’” he said.

It was the first time he’d faced something that felt viscerally anti-India. Not anti-outsider. “Was it anti-national?’ I asked him. He looked at it in an altogether different way. Road trips through the region over the years had taught him that bad policies by consecutive central governments have left people feeling distant from New Delhi. It had to do with time. “No media covers this,” he told me.

That said, his takeaway was clinical: “I don’t advise families or senior citizens to drive through Mizoram unless they absolutely have to. It’s a different world.”

That unease, both emotional and empirical, now lives in his logbook as a caution for others. He speaks of it without drama, as another data point. But it’s not just about roads and routes anymore. Madhu’s insights often double up as social barometers. That is when I made up my mind to join him on his next road trip to the region later this year.

He shared another episode from Uttar Pradesh. The Meerut-Delhi expressway was under construction, and his car got stuck on a detour through a village. As he reversed into a tight corner, a group of men surrounded him. His dashcam, meant to assist, was seen as a threat. Women nearby, washing clothes on the roadside, thought he was filming them.

“It was tense,” he said. “They didn’t care about the camera’s purpose. They cared about how it made them feel.”

He got out of it with a few scratches on the car and no harm to himself. But that incident, too, made its way into his caution protocols. Places where you can trust the gaze of strangers. Places where you can’t.

“When I travel with family or elders,” he told me, “I consider all this. Not just the road, but the safety around the road.”

He recalled guiding a female motorcyclist from Bangalore who refused to stop when he’d advised her to. She ended up with a flat, alone on a remote road. His first instruction? “Don’t remove your helmet. Don’t let anyone know you’re riding solo.”

He activated a chain of contacts, friend to friend, across regions. Within hours, she was escorted to safety. She never knew who all were involved. That, in Madhu’s world, is the point. No app will tell you what to do when the road breaks, or when the social fabric around it does. His network does.

And it’s updated in real time. Not by satellites, but by people who’ve lived the stories others have only mapped.

The Architect of Availability: A Tailored Approach to Convoy

Madhu’s capacity to accrue such extensive, granular knowledge stems directly from his profession. As a mathematics teacher in a coaching class, his schedule provides unique windows for prolonged road reconnaissance. "All of September is a holiday, all of March is a holiday for me," he said, "basically whenever my students take exams." These are not merely breaks; they are dedicated fieldwork expeditions into the arteries of the country, periods when his focus can shift from theorems to tarmac.

This sustained engagement with the road sets him apart. Most individuals, however, do not possess the luxury of such dedicated stretches of time for overland travel. Professional commitments and the relentless rhythms of contemporary life dictate finite windows. Madhu understands this constraint intimately. He describes how many within his circle, equally passionate about the open road but geographically or time-constraine d, circumvent this limitation: they often fly into a particular city to converge with him, joining for a specific leg of a journey rather than embarking on the entire cross-country traverse from their home base. He effectively becomes the mobile fulcrum around which these mini-expeditions coalesce, the constant presence on the ground who can coordinate and guide their limited immersion into the highway experience.

A Mission Beyond Commerce: The True Cost of the Road

This sophisticated support system isn't a formal club, Madhu insists. It's a "forum where all the like-minded people" converge. It is, he insists, very unlike the H.V. Kumar Fan Forum on Facebook.

There are tens of thousands of members here who log in to share their experiences. As for the group, it is a commercial venture. For anyone who wants to do a road trip, this is one of those places that allows you to choose their service to plan a trip. It has paid tiers and when members opt in, the forum will do everything from pointing to the routes, booking hotels, offering backend support, and watching over you, until you get to the destination. Once upon a time, Madhu used to work here.

He branched out though and decided to keep his operation non-commercial. He operates within a tight circle of friends and referrals. "I do it for not even 20-25 people in a month." Suddenly, I felt privileged that Ricky and he were watching my back when I was on the road.

But why do people such as him do that? Doesn’t it take away from precious time? His take is that the compensation he derives is found in the profound satisfaction of enabling others. "I enjoy helping people who travel."

[An authentic Mizo dinner in Khawlzal, near Champhai. Madhu’s car had broken down—but they brought him into their home, no questions asked, and served this meal. Strangers, only until kindness made them otherwise.]

The beauty of this informal organization lies in its trust-based foundation. "If it was a total stranger," he clarified, "I will just send the link." But for a trusted referral, a phone call is made, a hotel booked. In my case, for instance, I just didn’t have it in me to drive any longer. Between the both of them, they thought I ought to stop someplace. And Madhu booked me into a hotel at Hospet. As luck would have it, that was when I lost connectivity. It wouldn't be until the next morning that the booking link would reach me. And I ended up at a rather shady place that I wanted to get out of as early as possible.

But if I had gotten to the place that was booked for me, those interactions would serve as a subtle calibration process. It would allow Madhu to refine his recommendations for subsequent trips. And there are no profits in it for people such as him; it's about optimizing experience based on a progressively deeper understanding of individual needs.

His philosophy extends to the very economics of travel. While a multi-day road trip might consume 3.5 full tanks of fuel, accrue significant food bills, and necessitate multiple overnight stops—a cost that could easily rival a return economy class air ticket—Madhu views this expenditure differently.

"Traveling is the best form of charity," he insists, "because your money is distributed from the lowest person, like a puncture shop person, to the Government of India." It’s an economic philosophy woven into the very act of movement, transforming a personal journey into a dynamic system of widespread financial circulation, a small-scale engine for local economies.

The comfort that settled, knowing Madhu and Ricky were monitoring my drive, knowing their veteran oversight transcended the fallibility of digital maps, resonated deeply. This was not merely about navigation; it was about initiation into a brotherhood of the road, an almost invisible layer of human intelligence operating beneath the digital surface. It revealed a unique form of connectivity, trust, and mutual aid that functions as efficiently, if not more so, than any commercial enterprise.

Having witnessed Madhu’s oversight firsthand—the precision, the foresight, the unexpected rescue—the proposition of merely being "watched over" has evolved into an aspiration for direct participation. The intent is clear: like I articulated earlier, to join him at some point on his next trip, to move from being an observed subject to an active participant in this unique, human-powered system of navigation and mutual aid.

This is a different kind of journey. It is one where the destination is merely a waypoint. The true reward lies in the shared knowledge, the unforeseen assistance, and the quiet camaraderie of the open road — a network of human resilience that perhaps, in an increasingly algorithm-driven world, is the ultimate navigation system.