[Photograph CES 2012 - Haier by Doug Kline under Creative Commons]

By: Neelima Mahajan

(More on This: Also read an interview with CEO Zhang Ruimin)

If you are a normal human being, chances are that when the latest refrigerator model hits the market, you don’t go starry-eyed, as say, you would when you hear of the latest iPhone model or the Apple Watch hitting the market. And you will definitely not queue up for hours outside the store to buy said refrigerator.

Over the years things like refrigerators, air-conditioners and washing machines have become like commodities: functional, utilitarian and to a large extent, not aspirational.

That’s the challenge facing traditional industries now: how do you turn things like refrigerators, air-conditioners and washing machines into things that people aspire for? The answer lies in innovation.

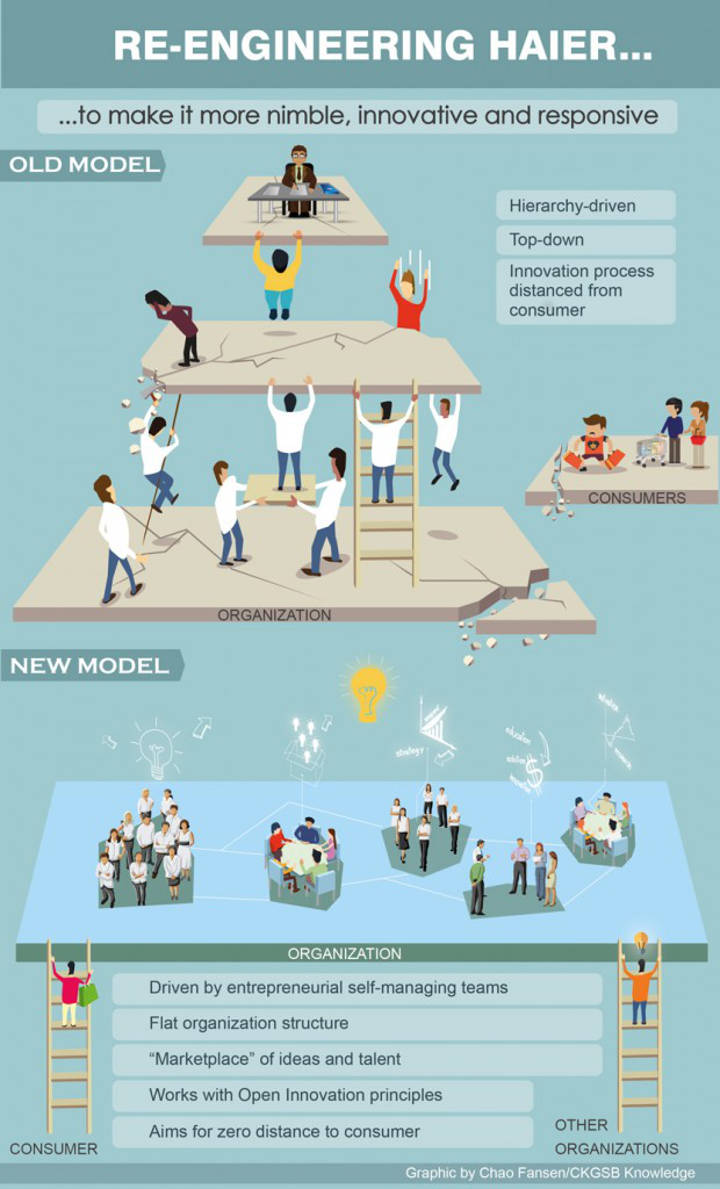

But here’s the next problem: how do you turn a traditional company in a traditional industry into an innovation powerhouse? Very often that requires reengineering a company’s DNA because traditional systems and processes often stifle innovation.

Yet one company seems to have found the magic formula.

The Qingdao-headquartered white goods manufacturer Haier has reinvented itself not once, but several times over to keep up with the changing times, spur innovation and stay competitive.

First, Break All the Rules

Zhang Ruimin, Haier’s Chairman and CEO, recognizes the impact of the digital era, especially how that has reshaped customer expectations and even the role of the customer in product creation. And so Haier is in the midst of yet another reinvention—it is turning itself into an internet-based ‘platform company’ made up of several micro-enterprises.

The idea is to create an organization that is extremely responsive to customer needs, constantly cultivates new ideas and innovates quickly. At the new Haier, among other things, you hear chatter of internet-based smart factories, wherein customers get a chance to personalize, say, their washing machine while still in the factory via a simple app on their smartphones. At the company’s corporate museum, apart from Haier’s historical innovations which included things like a washing machine that can wash sweet potatoes, you can see Haier’s futuristic innovations, such as a handheld washing machine that can easily fit into a purse and zap that offending stain while you are on the go. Or a device that allows you to try out different clothes without, well, actually trying them out.

But what does it really take to get there?

This is obviously not possible with the traditional organizational structure in place where ideas flow top-down and execution is done bottom-up. In the new Haier, hierarchies have been torn down and middle management has been shown the door. The aim is to turn the company into a flat organization which is a marketplace of ideas, talent and resources. So people with smart ideas will look for resources and people to bring that idea to fruition.

CEO Zhang Ruimin’s ambition is to turn Haier employees into micro-entrepreneurs who run their own micro-enterprises centered around an innovative idea or a product. They’ll be responsible for their own budgets and profit and loss, and will behave as independent business units under the Haier umbrella. That also means turning the compensation system on its head: instead of getting a fixed salary, employees will now be paid ‘by the customers’, essentially paid in accordance with the value they create. Zhang hopes that in the long run, some of these will become independent start-ups, with connections with Haier of course. That has already started happening.

In keeping with the principles of Open Innovation, the boundaries of the organization are porous so ideas can flow in from outside. But the company stresses that it is not doing traditional Open Innovation, but something it calls ‘Platform Open Innovation’. As Wang Ye, Vice President, Haier, puts it, “Almost all companies do different degrees of Open Innovation, but [the speed of innovation is very fast] when outside [the company] but it’s very slow [once inside the company] because you have to follow the processes of the company: [the speed of] the company’s processes [impacts], the [speed of] innovation.”

So Haier has torn down the “walls” between itself and end users and itself and external partners (like design companies and various links in the supply chain) so that the speed of communication between end users and partners is faster, and the speed of innovation is faster.

Stepping Into the Wide Unknown

This is by all accounts an audacious plan. Few companies dare to implement a business model that is so radical. Some companies use some elements of it. Such as Morning Star, the world’s largest tomato processor which practices something called ‘self-management’: so every person is, like in Haier, “their own CEO” and pretty much autonomous. At Morning Star autonomy comes hand in hand with responsibility and discipline, however counterintuitive that may sound.

At the heart of Haier’s dramatic transformation is its quest to continue to stay relevant and avoid becoming a ‘has-been’ commodity producer. So Zhang is throwing the old rulebook on management out of the window, and creating his own.

Experts say that Haier is unlike most industry incumbents who are comfortable doing what they’ve always done in the past to be successful, and are often disrupted by new entrants from outside who come and eat their lunch. Remember how Apple revolutionized smartphones, while incumbents like Nokia, Sony-Ericsson and Motorola stood by the wayside? We all know what happened next.

“Haier’s consistent experimentation with future possibilities allows it to be more agile and more open to the ideas of the new market entrants, than being hostages to the past,” says Bill Fischer, Professor of Innovation Management at IMD and author of Reinventing Giants, a book that chronicled Haier’s previous transformations.

Fischer, who has watched Haier and Zhang for 20-plus years, feels that Haier is stepping into the unknown, creating its own path as it moves along. “We are all learning as we go, and that becomes a major challenge for organizations that need to make big strategic changes, quickly, without adequate reassurance that these are even in the right direction,” he says.

The lack of a similar precedent doesn’t help, and Haier will have to look for cues elsewhere and rely on its gut. “There are lessons to follow in such situations, but they are likely to be found in unlikely places,” says Fischer.

The People Challenge

Adapting to change that shakes up the whole organization—employees, systems and processes—leaves people unsettled, and can cause a sense of unease in the organization. Take the idea of being paid by the end user for value created as opposed to getting a fixed salary. That itself has the potential to add tremendous discomfort. People can work very hard on a project and in the end their efforts might come to naught.

Add to it also the element of internal competition that has come to roost in Haier: people competing against one another so their projects succeed. Some internal competition can be healthy, but it can also become brutal. “The competition does push people to be creative, innovative and use limited resources with great efficiency, it really equates to achieve outcome even with limited resources. This is obviously the positive side. The negative side is competition could be demoralizing for some, and make people feel less empowered,” says Dennis Campbell, the Dwight P. Robinson, Jr. Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. “That’s a tension that is certainly felt in that model but when you look at where Haier is evolving now… [you’ll see] CEO Zhang’s willingness to adopt and adapt them very quickly and where necessary.” As Fischer puts it, “Polite teams get polite results.”

Haier believes that internal competition can help filter out the “low-efficiency projects”—and people. Those who can’t survive in this system end up leaving, leaving behind hopefully the best of the lot. “They created market forces inside the firm. People that don’t want to change or adapt would quickly be wiped out of a system like that,” says Campbell, who recently wrote a case study on Haier. “I think that people that are entrepreneurial are going to be attracted to a system like that. People that are already Haier employees see opportunities to become entrepreneurs—they will seize the opportunities.”

Zhang acknowledges the fact that there may be a sense of unease and appears to be comfortable with that. He says: “On the [managerial] back end, if [someone] can’t show any visible results after we illustrated an idea thoroughly, then we have no other choice but to ask him or her to leave. As a matter of fact, more than 50% of the [former] vice-presidents at Haier have left. On the contrary, those who can innovate and think outside the box will be greatly valued and favored.”

At some level, Haier employees have come to expect change. Change has been a part of the Haier ethos for the last 30 years at least. Says Fischer, “While I certainly think that any such big change, in any organization, can be considered as ‘unsettling’, I also believe that Haier has done an extremely good job of building a ‘social architecture’ within the organization that reduces the fear associated with such change.”

“It’s also important to recognize that in its previous change experiences, Haier has always retained some familiar aspects of the work environment, so as not to be creating complete change all at the same time,” he adds. “I think that this matching of big change with a retention of some of the familiar helps employees adjust to the new requirements in much easier manner; not everything is unfamiliar.”

Cascading the Vision

All said and done, one big question still remains: can Haier rise beyond Zhang Ruimin’s own vision? For 30-plus years, the company has been steered by Ruimin and his unique ability to foresee things and push change through, a capability not every CEO has. As Campbell puts it, “I think it takes a certain kind of person at the helm to do that.”

But is Haier too dependent on Zhang? “It’s fair to have that question. I don’t know the answer to it,” says Campbell. “I think it’s going to be dependent on somebody having his leadership style, be willing to embrace change in that way, that does take a certain leadership style. Ultimately the answer to that question is whether it survives him.”

Over the years, Zhang has infused Haier with certain capabilities that most organizations find hard to replicate. “Organizational change is hard and building an organization where change is just part of its DNA and change happens rapidly and quite frequently, that’s highly unusual,” says Campbell. “It does take a strong leader to make that work.”

Besides Haier has ‘institutionalized’ some principles such as the “zero distance to customer” principle, something that has remained constant over the years even as the organization itself went through massive change. So at the end of the day, as Campbell says, “There is a clear direction and a very clear principle, that I think helps a lot.”

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]