[A herd of wildebeest prance around before the migration across the Mara River]

3 AM at Kati Mara Camp, Northern Serengeti

The tent trembles, jolting me awake. Disoriented, I wonder: is this the Great Migration? No, this is primal terror. The thunder of hooves, the scent of panic—wildebeest stampede past our camp. Then, growls: low, rumbling, close enough to feel in my ribs. The lions are hunting tonight.

I came to Tanzania chasing a memory from James Michener’s The Covenant—two horsemen, motionless as wildebeest flowed around them like a living river. Twenty years later, I’m separated from that same migration by nothing but canvas. Michener made it sound poetic. Reality is different. The air is thick with the musky scent of sweat and the damp, earthy aroma of trampled grass.

The emergency whistle digs into my palm. Stay inside. Sound the alarm if they breach. The camp manager’s rules were meant to comfort, though we all know the truth: if lions want in, a whistle won’t stop them. But the wildebeest will. There are always more wildebeest.

The hunt ends abruptly. Silence settles, broken only by the whimpers of stragglers. Somewhere beyond our tent, lions claim their prize. Sleep won’t come, so I trace our journey through Tanzania over the last few days.

Onwards from Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam hums with the energy of one of East Africa’s most important ports. Long-haul trucks stream out of its harbour, bound not just for the Tanzanian interior but for far-flung neighbours like Malawi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The port’s reach stretches deep into the continent, and with it comes the slow, inevitable congestion—a tangle of trucks, cars, and three-wheelers—called bajajis, though they’re made by TVS—weaving for space on sun-baked roads. Steep fines keep drivers from leaning on their horns, so the movement is noiseless despite the gridlock.

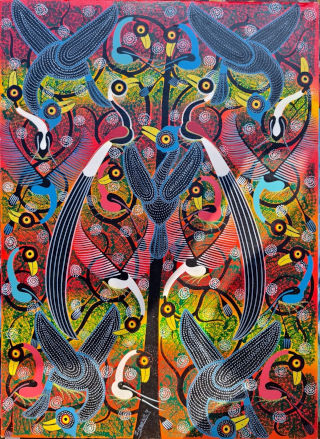

[Tinga Tinga is a bold and colourful East African art style that began in Tanzania. It is known for its intricate patterns, playful storytelling, and vibrant depictions of wildlife.]

Beyond the traffic, the city moves pole pole—slowly—like India three decades ago, before liberalisation. Life here feels peaceful, but also plodding, as if shackled by policy. Some of that same unhurried chaos spills into travel. Our local flight from Dar es Salaam to Kilimanjaro is cancelled, and we are moved to another—only for the same thing to happen on our return. Here, you learn to roll with the flow. And when you do, the city rewards you: clean, uncrowded beaches; corner shops glinting with green malachite jewels; high-end stores gleaming with tanzanite gemstones—a special blue-purple precious stone found only near Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Local markets come alive with shouts of Jambo! Karibu! (Hello. Welcome) and the riotous reds, yellows, and blues of Tinga Tinga paintings.

Kilimanjaro to Ngorongoro

We flew from Dar es Salaam to Kilimanjaro to begin our safari. Rising alone from the plains, Kilimanjaro is the world’s tallest free-standing mountain. Though just three degrees south of the equator, its summit is capped with snow—a striking sight in the African heat. The slopes rise gradually, drawing trekkers from around the world. Those who climb pass through a changing world in miniature: cultivated farmland at the base, dense rainforest, alpine desert, and finally the stark, icy summit.

[Kilimanjaro, known as ‘Roof of Africa’ , rises above the clouds]

Our guide and driver, Hussein, was waiting for us outside and beside him stood our safari vehicle—a modified long-wheelbase Toyota Land Cruiser, painted in the muted brown that blends into the landscape. Its roof could pop up for 360-degree viewing; the sides were lined with wide sliding windows. Heavy-duty suspension, oversized all-terrain tyres, and two spare tires at the back hinted at the distances and terrain ahead. Inside, there were seven passenger seats, each with a clear view, and just enough room for camera bags and daypacks. This was to be our home on wheels for the next several days.

From Kilimanjaro, we drove west through farmland and scattered towns, the landscape shifting slowly to hilly terrain. We stopped at a village called Karatu, where over dinner, the staff regaled us with song.

The next day, we set off early in the morning. The Ngorongoro Crater was formed about 2.5 million years ago, when a massive volcanic mountain, believed to have been higher than Kilimanjaro, erupted and collapsed in on itself. Rains turned the volcanic ash into fertile soil, and over the years, a secluded ecosystem took shape here. Other than the birds and humans, no one crosses the boundaries of the crater.

[The Ngorongoro Crater stretches below. Located in northern Tanzania, it is the world’s largest intact volcanic caldera, formed two to three million years ago when a massive volcano collapsed. Spanning 19 km across and 600 m deep, this UNESCO World Heritage Site hosts one of Africa’s densest concentrations of wildlife.]

The crater announced itself first through the mist—a lost world veiled in cloud. As we descended, the vapours parted like theater curtains. Suddenly, 19 kilometres of primordial Africa lay before us—a scale so vast, Bangalore’s urban sprawl became my involuntary measuring tape. KR Puram to Bellandur. Whitefield to HAL. All contained within this perfect bowl.

[A pride of lions and lionesses at a kill]

As we descended, the first thing we saw was part of a lion pride that had just made a kill. The lionesses were crouched over the carcass, tearing into it with quick, efficient movements, while the male sat a short distance away, already satiated.

[Gazelle engage in playful fights; each zebra has unique stripes]

Further on, gazelles grazed in small herds and zebras swished through golden grass alongside wildebeest—nature’s odd couple, one grazing long stems, the other cropping short. Down on the crater floor, the lakes shimmered with ribbons of pink flamingos. Then came a rare treat—a serval cat, the size of an indie dog, slender and long-legged, stalking through the grass in search of smaller prey. In the open light of the crater, every movement felt amplified, each sighting set against the sweeping backdrop of its circular walls.

[The flamingo takes its colour from food it eats]

Olduvai Gorge to Central Serengeti

The next day, we drove northwest toward the Serengeti, stopping at Olduvai Gorge. Here, some of the oldest known fossils and stone tools have been uncovered; remains from a species that predated even Homo erectus. These finds rewrote the timeline of early human evolution, placing this part of Africa at the very heart of our origin story.

[Giant skull replicas mark Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, often called the “Cradle of Mankind”]

The road ahead led us deeper into the Serengeti—’endless plains’ in Maasai. A name that becomes obvious as you drive for hours, yet barely cross its vast expanse. Dirt roads crisscross the grasslands, but there are few markers. Hussein explained that it takes time for drivers to learn their bearings here. Guides keep in constant touch over walkie-talkies, passing sightings by using special names for distinct rocks and landmarks. Strict rules keep vehicles on the roads, so some sightings are from a distance.

[A leopard rests high in a tree; a resting male lion. Lions can sleep up to 20 hours a day, conserving energy for the intense bursts of strength needed to defend territory and hunt]

The animals here are long accustomed to safari vehicles. We saw cheetahs stretched out in the shade and lions dozing by acacia thickets, barely lifting their heads as vehicles idled metres away. Much of the day was spent driving between points—long stretches of nothing, broken suddenly by the sight of a herd or a solitary predator. It reminded me of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, where John le Carre describes detective work as long periods of waiting between brief bursts of action. Here, too, the excitement came in spikes.

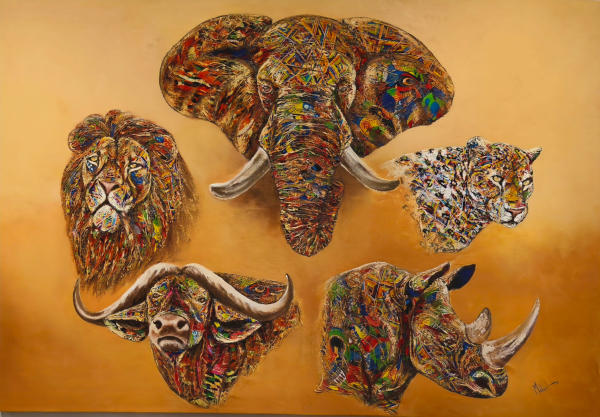

But the waiting had its own calm. The land rolled out in an unbroken sheet of gold, and between sightings we could let our minds wander, the camera always within reach in case the next turn brought something extraordinary. By late afternoon, we had ticked off four of the Big Five—elephants, lions, leopards, and buffalo—and learnt their Swahili names: Tembo, Simba, Chui and Nyati. We also saw hippos (Kiboko), giraffes (Twiga) and wildebeest (Nyumbo).

[Hippos stay underwater most of the day; giraffes often twine their necks in affection]

By evening, we reached Tampa Resort, our base in the Central Serengeti. The camp blended into the landscape: canvas tents set on raised platforms to prevent snakes from crawling in, views stretching over the open grasslands, and the night sounds of the bush drifting in. It was the kind of place where you could sit under the stars, hear a hyena call in the distance, and know that the Serengeti was all around you.

But the serenity here never lets you forget that this is still the true wild. We were warned not to walk alone after dark; predators roam close to camp. The rule was simple: signal with a torch, and someone would escort you.

[A red-billed oxpecker sits on a Cape Buffalo, one of Africa’s most formidable herbivores. The bird feeds on ticks and parasites living on the buffalo’s skin]

One night, after dinner, we were being walked back to our tent when our escort suddenly stopped. The beam of his torch caught two glinting points ahead—the eyes of a Cape buffalo. He waved his arms and shooed it off, then told us there had been three of them here the previous week. Lions had hunted down two, and the last one was still being stalked. If it wandered near our tent, it would be in real danger. That night, distant roars mingled with gazelle cries. In the morning, blood stains on the driveway told their own story.

Northern Serengeti and the Mara River

From Central Serengeti, we moved north the next day, into the section closest to Kenya’s Maasai Mara. At the boundary between the two, we came across a startling splash of colour in the muted tones of the savannah. It looked as if the radioactive spider that bit Peter Parker had been swallowed whole by a lizard. This was the famed Agama—the Spiderman Lizard—its body split into a vivid red head and torso, and an electric-blue tail and hind legs. In a landscape where blending in is often the difference between life and death, it was almost brazen in how much it stood out.

[The Agama Lizard, popularly called Spiderman lizard; the cheetah is built for the chase. It can sprint up to 100 km/h in short bursts, using its slender build, long legs, and deep chest for explosive speed. It stalks prey before launching into a lightning-fast pursuit]

Later that day, we watched a distant cheetah make an attempt at hunting wildebeest. By now, I barely noticed the herds of wildebeest, gazelles, and zebras that filled the plains. They had become the constant backdrop of the Serengeti, so common that their presence felt almost like part of the landscape itself.

By late afternoon, we reached the Mara River. Hordes of wildebeest clustered at the bank, the air thick with anticipation. We hoped to see the great crossing, but wildebeest are skittish. They would prance and mill about, edge toward the water, sniff the air, perhaps catch sight of the crocodiles lying in wait, and then turn back. This ritual repeated again and again, each retreat dampening the hope that today would be the day.

As the light began to fade, Hussein gave the call. We had to leave. The crossing wouldn’t happen now, and tomorrow’s window was narrow. We would have to depart by 10:00 a.m. to make our next stop, seven hours away. That night, we reached Kati Mara Camp, still hoping that morning would bring the sight we had come for.

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

6 AM, Kati Mara Camp, Northern Serengeti

It’s our last chance to see the great migration. We wake to the chill of the morning and, as per camp instructions, shout, “Water!” A staff member appears and fills a bucket outside our tent, which feeds into a small shower. The shower has two handles—one to start the flow, one to stop it—and a strict allowance of 20 litres per person. Run out, and you call for “More water!” until the camp’s total limit is reached.

We leave the camp by 7 AM. The crossing point isn’t far, but when we arrive, a line of safari vehicles is already in place. The wildebeest seem livelier than yesterday, but the crush of vehicles near the bank appears to confuse them. Rangers arrive and ask the closest jeeps to move back, opening a path to the river. The air hums with expectation. I glance at my watch—9:30 a.m. Will it happen in the next thirty minutes, or will the herd lose its nerve again? We tell ourselves, “At least we’re here.”

[The Great Migration across the Mara River]

Then it comes—the thunder of hooves. The wildebeest are running. We swing into position just in time to watch them plunge into the Mara. The current pushes them into a wide arc as they run, swim, and leap their way across. They cross in groups of fifty, then a hundred, the water churning with their movement. Today, there are no crocodiles waiting. Every one makes it cleanly—except for one straggler, which drags itself onto the far bank and collapses. We think it’s drowned, but a few minutes later it coughs up water, staggers to its feet, and lopes away behind the herd.

This scene will repeat over and over in the coming weeks as nearly two million wildebeest make the journey from the Serengeti to the northern side of the Mara River, some pushing on into Kenya’s Maasai Mara. There they will breed and spend four months grazing on the tender short grass, before reversing the journey—crossing back into the Serengeti, moving south through the central plains, and starting the cycle all over again.

By the time we head back to our next stop, the adrenaline of the crossing is still in the air. The memory of the wildebeest plunging into the Mara, the spray of water, and the churn of hooves, feels like the kind of sight you travel across continents for. It is raw, unchoreographed, and utterly unrepeatable in the same way twice.

The Serengeti marches to its own rhythm, offering moments of tranquility and raw, wild urgency, often within the same day. From Ngorongoro’s hush to the Mara’s tumult, from a cheetah’s stalk to a lion’s prowl—each moment is part of an ancient cycle. As you depart, the Serengeti continues its timeless dance, indifferent to your absence, yet forever etched in your memory.

Travel tips

[A painting of the Big 5, called so because they were the most ferocious to hunt]

Best Time to Visit: For the Great Migration in Northern Serengeti, aim for late July to early September. Ngorongoro Crater and Central Serengeti have wildlife year-round, but the dry season (June–October) offers easier sightings and fewer mosquitoes.

Park Fees and Permits: Park entry fees are high ($70 - 80 per adult/day for Serengeti), so plan your route to minimise re-entries. Most of the permits are paid for in advance, but online payments in Tanzania may work only through SWIFT and not Paypal or credit cards.

Vaccinations: Yellow fever vaccination is mandatory. Only government hospitals provide WHO approved vaccines in India, and many have long waiting lists. Find out who provides these in your city and plan for these in advance. You can get them on arrival at Tanzania, but they cost a lot more ($100 vs Rs 440 in India). Some transit countries like Ethiopia also recommend polio vaccination.

Safari Vehicles: Most operators use modified Toyota Land Cruisers with pop-up roofs for viewing. Be warned, the rides are long and bumpy as there are no roads within the park. You will be in the vehicle for 8 hours or more every day, so if you have motion sickness or back pain, take medication accordingly.

Connectivity and Charging: Mobile coverage is patchy inside parks. Camps often run on solar power with charging stations. Bring a power bank for cameras and phones.

Staying in Tented Camps: At night, predators wander through unfenced camps. Don’t walk alone after dark. Use the camp escort system, and keep your torch handy for signalling.

Cash and Currency: Carry USD in small denominations for tips and emergencies; Tanzanian shillings are better for local markets. ATMs are scarce outside major towns like Arusha or Karatu.

Ngorongoro Crater Access: Descent into the crater is limited to certain hours and vehicles must return the same day, so start early. Mornings are misty; clear views often come mid-morning as you descend.

Clothing and Gear: Pack neutral-coloured clothes (avoid bright whites and blues which attract tsetse flies). A light jacket is useful for chilly mornings, and a cap or wide-brimmed hat is essential under the midday sun.

Tanzanite Jewellery: Tanzanite is found only in Tanzania, near Kilimanjaro, and ranges from pale lilac to deep violet-blue. Buy from certified shops (often in Arusha or larger towns) that provide a certificate of authenticity; avoid street vendors for high-value stones.

Editor's Note: Hungry for more on nature's greatest spectacle? Read D.N ‘Bonny’ Mukerjea's recounting of a Kenya safari