[An Aadhaar enrolment camp at Nawada, Bihar. Photo from UIDAI]

Across the world, there is a growing interest in India’s decade-long experiment and experience of using technology to solve hard problems. How to ensure state welfare programmes reach the poor? How to deliver finance—savings, insurance, loan and investments—to those left out by traditional markets? Broadly, how to offer the impoverished a whole range of services the privileged take for granted? And how to do it at scale—for a billion?

The social sector, government and businesses have all shown interest in India’s experience with Aadhaar and India Stack. Bill Gates, who in his philanthropist avatar wants to solve societal problems using technology, recently said he was interested in how “the lessons from India apply to other countries for things like digital identity or financial services.”

Politicians and officials from other parts of the world have been visiting India to study and understand how it’s being built and rolled out. Morocco has taken one step further, building its identity system on an open-source platform that emerged out of India.

In November, tech giant Google sent a note to the US Federal Reserve Board urging it to implement a payment platform similar to India’s UPI.

India’s approach, a recent paper from Bank for International Settlements argued, “offers an important case study where the results are relevant and applicable for all economies, irrespective of their stage of development.” Commenting on the paper, Financial Times added that India had left “many advanced economies playing catch-up.”

Digital infrastructure as a public good

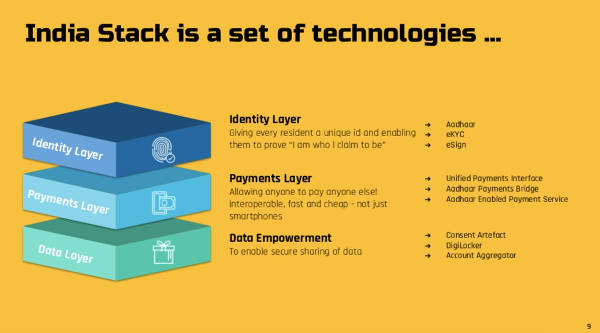

Their interest is in a group of technologies collectively called India Stack. It is a bunch of application programming interfaces (APIs) that allow a user to do some very basic things: authenticate identity (through Aadhaar and eKYC), sign and share documents (eSign and DigiLocker), make payments (UPI), share data (Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture)—all of these digitally. These technologies were built over the last ten years as platforms, as public infrastructure, that can be accessed by the social sector, government and businesses.

India Stack has had scale and impact. Last week UIDAI announced that Aadhaar has been issued to 1.25 billion people—one-seventh of the world population. In September, Reserve Bank of India said that UPI had overtaken debit cards (more popular in India than credit cards) in both transaction volumes and value. In October, UPI saw more than a billion transactions, and in December it crossed 1.3 billion transactions.

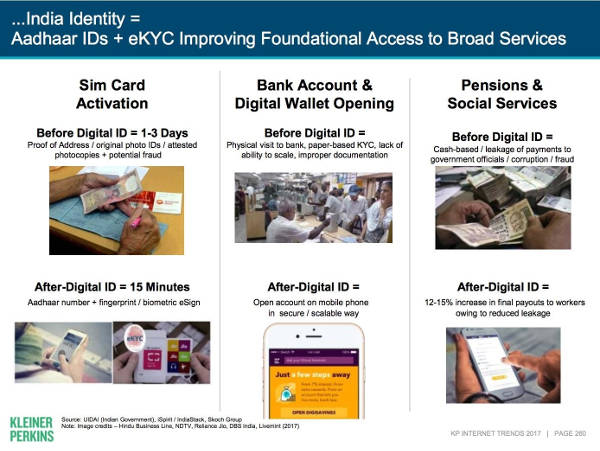

Aadhaar and eKYC helped in financial inclusion. The Global Findex Database 2017 noted that “between 2014 and 2017 [bank] account ownership in India rose by more than 30 percentage points among women as well as among adults in the poorest 40 percent of households.” It coincided with use of Aadhaar and eKYC for bank account opening.

The recently published The State of Aadhaar survey showed that Aadhaar was the first-ever ID for 8% adults, 15% homeless and 14% trans people. Eighty percent felt it made welfare delivery more reliable; 92% were somewhat or very satisfied with Aadhaar.

Digitisation and its discontents

The last two numbers also tell a story that is easy to miss. In a country of 1.3 billion, even a small percentage means a big number in absolute terms. Keeping 80% of Indian population happy would leave out the equivalent of 80% of the US population. Keeping even 99.5% of India’s population happy would leave out the equivalent of 100% of Singapore’s population.

This kind of scale has serious implications. Inviting over a billion people into the world of digital technologies also means exposing them to the attendant risks all technologies face—of fraud, security, flawed implementation and exclusion. Consider also the huge inequality in other enabling infrastructure such as mobile networks and internet, and understanding how digital technologies operate.

Yet, to do nothing means denying the poor the benefits the privileged enjoy. To argue we have gotten so far without relying on digital technologies would be to tell them ‘wait for another 30 to 50 years, you will get there too’.

India’s path in the last ten years was forged by these two conflicting forces—the promise of digital technology, and the perils that inevitably come with it.

The heat and dust of tech in society

Those who want to learn from India’s experience are confronted with three challenges.

1. They have to walk through the dust kicked up by various groups arguing about the impact of India Stack, especially Aadhaar—whether it’s good or bad. Binary debates are too focused on the “whether-to” questions—they seldom leave room for “how-to” discussions.

2. The Indian approach questions some widely held assumptions about the use of technology. To name just two: Biometrics is mostly associated with security and criminal investigation, and has negative connotations. But, Aadhaar used it for social welfare and inclusion. Similarly, we instinctively associate the word data with protection. But, the focus of India Stack is about sharing it securely to get something of value in return. Both examples demand a change in mindset.

3. There are no ready-made templates. India’s was an evolutionary process that involved a lot of thinking and a lot of doing. Shankar Maruwada, who co-founded analytics firm Marketics and sold it to WNS before joining UIDAI to head marketing, said it was a think-do-think-do-think cycle. “The feedback loops are strong and flexible. The lessons learnt from one activity, from one project is applied to the next. Learning is continuous.”

This demands a different mindset. It recognises that what we have today is not perfect. It continuously seeks feedback, from both admirers and critics. It acts on that. And it constantly evolves.

How to design for scale—in five questions

That’s why the lessons that emerge out of India Stack can at best be explored by asking questions. Here are five:

- How do I enable people closest to the solution to solve their problems, instead of offering a cookie-cutter solution?

- How do I work with the ecosystem comprising the social sector, state and businesses?

- How do I ensure the basic principles remain the core of the system, even as the applications and uses expand?

- How do I effect systems change, not just a change in a segment?

- How do I think long term, and still make it real for today?

#1 How do I enable people closest to the solution to solve their problems, instead of offering a cookie-cutter solution?

India Stack’s ardent supporters and fiercest critics seem to agree on one thing: that it’s designed as a solution for the toughest problems facing India today. The only difference between the two groups is that while supporters think it lives up to its promise, critics think it does quite the opposite.

However, there is a fundamental error in both, in that India Stack is not a solution, it’s a platform on which solutions can be built—someone must build those solutions, and those solutions must work in the real world.

Giving a fish vs. enabling food production

Pramod Varma, chief architect of UIDAI speaking at World Bank’s Identity for Development (ID4D) event held at the United Nations headquarters in New York in 2017 said this about Aadhaar: “It does not give any entitlement. Zero. Not citizenship. It does not guarantee food. It does not guarantee a job. It does not guarantee (access to) banking. It does not guarantee anything. All it does is provide you with a unique identity.”

It’s counter-intuitive. Building a bunch of APIs was not how governments traditionally solved problems. Policymakers and bureaucrats sitting in Delhi and state capitals came up with plans that tried to take the problems head-on. If the country had too many polio cases, they ran a vaccination drive. If crops failed, hitting farmers’ incomes, they announced loan waivers. They built clinics and schools, gave away medicines, and subsidised food grains.

Some of those interventions worked (for example, India’s campaign to eradicate polio.) But many didn’t. They got bogged down by the country’s vastness and diversity. India’s human development indicators (and reports such as ASER) serve as a reminder of the failures of centralised, cookie-cutter solutions.

What if centralised interventions are limited to ‘enabling’ people closest to the problem to solve the problem?

That’s the thinking behind Aadhaar and India Stack. “We said we should not be solving subsidy. We should not be solving health issues. We should not be solving education issues in a silo. If we believe that we can solve for a large country like ours, that means we assume we know the solution. And almost always a bad assumption,” Varma said.

“You don’t know the solution to the problem, most of us don’t know,” he added. “And so solutions actually end up going stale very quickly. And so you need something that can evolve, like biological parts, like people. We need…new solutions, a new way of doing things to emerge and evolve rapidly. For that to happen, we need a platform approach. We need an infrastructure approach.”

It’s the difference between giving hungry people fish and enabling them to produce any food of their choice.

One way to understand this approach is to look at what platform businesses do. YouTube does not produce videos but provides a platform for producers and consumers to discover each other. As a result, it has achieved the kind of scale and customisation that a movie producer could never have.

Here’s a short video of Sangeet Paul Chaudary, author of Platform Scale and Platform Revolution, explaining its dynamics.

The rabbit hole to a bad place

However, when you depend on others to build the solution, you will also have to account for the fact that shoddy solutions will be built. YouTube doesn’t just have educative videos like the one above, it’s also littered with trashy, problematic content. When states and district administrations started building solutions based on Aadhaar, they also invariably built badly designed solutions. In one case, Aadhaar-enabled public distribution system (PDS) allowed only the head of the family to access rations from the system.

Sanjay Purohit, who was chief strategy officer and head of banking practice at Infosys before moving to the social sector, spent months studying Aadhaar and India Stack. He says, designing for scale means you have to ask how to design for divergence, rather than for convergence. “Don’t expect that users will over time come around to doing things in a specific way. Instead, keep in mind that they will act, adapt in ways you never imagined.”

That is the strength and weakness of the infrastructure approach. The questions that follow hint at how to address some of the weaknesses.

#2 How do I work with the ecosystem comprising the social sector, state and businesses?

Former McKinsey boss Dominic Barton says, to lead in the 21st century, one has to be a “tri-sector athlete” who is “able to engage and collaborate across the private, public, and social sectors”. Purohit says to serve a billion people, one has to design for samaj (society), sarkar (government) and bazaar (market), working together and amplifying each other’s efforts.

India Stack is a good example of how these collaborations took place. Aadhaar could roll out fast (it reached the billion mark in just five-and-a-half years, faster than any other digital platform) because UIDAI, in its early years, designed for speed and scale. Essentially a department in the Planning Commission, it had talent flowing in seamlessly from business and civil society. It used both public and private sector effectively for enrolments. The other elements of India Stack were built in collaboration with government, regulators, or a body such as the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) which is owned by banks, and with inputs from businesses and civil society.

The India Stack’s story also underlines how difficult and unpredictable that path can be, with support and resistance coming from all the three.

When Aadhaar-enabled eKYC was launched in 2012, it offered a better alternative to the way people shared proof of identity and address to open bank accounts or get telephone connections. ‘Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door’—that’s pretty much what happened to eKYC. Banks and telecom companies embraced it with enthusiasm. It helped them onboard customers faster and cheaper. It made it to Mary Meeker’s hugely popular annual Internet Trends Report in 2017.

Lower transaction costs also meant bigger, and therefore, more inclusive market, Sanjay Jain, a project manager at UIDAI, and one of the core members of India Stack pointed out. If a financial services company is working on a commission of 50 basis points, its breakeven ticket size would be Rs 10,000 if the transaction cost is Rs 50. The breakeven ticket size would drop to Rs 400 if the transaction cost is just Rs 2. Digital brings the transaction costs down, allows for sachet-sized transactions, and as CK Prahalad explained in Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, the poor get market access. Inclusion follows.

In 2014, the Indian government launched Jan Dhan Yojana, pushing the system to open bank accounts for the poor. Aadhaar authentication and eKYC helped. The share of adults having a bank account touched 80% in 2017 (it was 35% in 2011).

One of the biggest beneficiaries of eKYC turned out to be Mukesh Ambani’s telecom venture Jio. Armed with biometric-enabled tablets for Aadhaar authentication and getting eKYC data, Jio’s agents signed up 200 million subscribers in less than two years.

The dark side of the moon

Aadhar rollout and adoption by various state departments and businesses also revealed what could potentially go wrong when technology hits the road. Government agencies unwittingly revealed millions of Aadhaar numbers on their websites. Fraudsters made money selling fake Aadhaar enrolment apps, and login credentials that allowed them to access user data. Badly designed applications, bureaucratic indifference and some inherent limitations of biometrics led to exclusions. Demand for ‘Aadhaar cards’ by a range of state agencies—in government crematoriums and for the issue of death certificates, for example—resulted in inconvenience and general discontent. Government’s push to make Aadhaar mandatory, by forcing people to connect it to their PAN cards for example, intensified fears of it being used for surveillance.

Meanwhile, two successive governments had trouble passing an Aadhaar law. Congress-led United Progressive Alliance didn’t because BJP was opposed to it (a joint parliamentary committee headed by former finance minister Yeshwant Sinha gave its thumbs down to Aadhaar) and BJP-led National Democratic Alliance struggled because Congress, despite being the one to start the project, opposed it for mostly political reasons. Finally, in 2016, BJP passed it as a money bill, which didn’t require the sanction of the opposition-dominated upper house.

Activist groups approached the Supreme Court to strike down the Aadhaar law, saying it was unconstitutional. After many twists and turns, a five-judge bench at the apex court upheld the constitutional validity of Aadhaar but struck down Section 57 that allowed private players to use the UIDAI platform. It meant, businesses lost access to Aadhaar-enabled eKYC process—and with it went the efficiency gains, cost savings, and the promise of inclusion mentioned earlier.

The unintended consequences

However, the irony is this: activists were mostly fighting against Aadhaar because of the government’s association with it. Activists from the development sector were opposed to Aadhaar because it could disrupt government welfare programmes. Privacy activists were fighting it because they were worried about government surveillance. At that time, arguments that Facebook, Google, and broadly smartphones, were also threats to privacy were countered by pointing out that people signed up for them voluntarily. However, when the court ruling finally came, nothing significantly changed for the government. The one big casualty was the private sector’s loss of access to the Aadhaar authentication platform.

Eventually, by amending the Aadhaar Act, and tweaking other laws and tech, eKYC was revived—but it had lost some of its convenience and sheen.

However, the legal battles had at least two important consequences that helped India take the right path. One, the Supreme Court declared privacy to be a fundamental right. Two, the case itself forced the government to push the pedal harder on passing a personal data protection legislation.

#3 How do I ensure the basic principles remain the core of the system, even as the applications and uses expand?

When you are looking at a big scale, working with government, social sector and businesses, each sector with its own inherent sets of values and assumptions. It will be impossible to get the culture right. But one can strive to ensure that the basic principles are not violated.

The story of eKYC—the initial resistance from the leadership, adoption, expansion, and conflicts that came up with scale—underscores the need for tweaks and mid-course corrections.

In the early days of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), the leadership team faced a dilemma on whether to get into eKYC at all. The demand for physical copies of Aadhaar picked up soon after government agencies and regulators started accepting Aadhaar as a valid proof of identity. Aadhaar holders were giving out photocopies of letters from UIDAI as proof of identity, address and date of birth. Within UIDAI, it kicked off a debate on how to deal with it. Is it not a better idea to make the process digital? It will be cheaper, faster and more secure. After all, no one knew how the photocopies of our driver’s licence and passport were being used between the time we give them to an agent and the time it reaches a bank or a telecom.

But, there was resistance to this idea, including from the top two in the UIDAI hierarchy, its then director RS Sharma, and then chairman Nandan Nilekani. They were reluctant to expand the scope of an already ambitious project. Also, as a principle, UIDAI did not want any data to go out of the system, except to say if the Aadhaar number and biometrics of a user matched. Sharing demographic data would violate that principle.

However, Nilekani changed his mind after a discussion with Ashok Pal Singh, an IAS officer who was on deputation from India Post, after one of their meetings with bankers in Mumbai. Singh told his boss that UIDAI was only a custodian of users’ data and not its owner. The data belonged to people, and if they wished to share it with any entity, UIDAI had an obligation to do it in a secure manner.

That struck a chord with Nilekani, and soon, others saw the point. UIDAI’s technology team, based in Bangalore, headed by Srikanth Nadhamuni, and driven by UIDAI chief architect Varma and project manager Sanjay Jain, put their heads and hands together to design and build eKYC. By September 2012, it released the APIs for eKYC.

In some ways, DigiLocker is an extension of eKYC. While eKYC was about sharing data existing in a single organisation, UIDAI, DigiLocker aimed at enabling sharing of data—ranging from birth certificates, driving licence, mark sheets—lying across various government departments.

[In three slides: How eKYC, DigiLocker and Account Aggregators work. Click the forward arrow on the slides to see the next one.]

Now, the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) takes the idea of DigiLocker and pushes the boundaries even further to include data held by the private sector, which generates a far larger number of documents—your bank statements, telecom bills, blood reports.

Through all these, the core principles remained. The data belongs to the people. The government or a business is merely a custodian of that data. Thus, the government and businesses should not only protect the data—and this is the thrust of most data protection laws—they should also let the data owners securely share their data with any other entity as they deem fit. eKYC, DigiLocker and DEPA are designed to do it.

The tougher part is to get the different players in the ecosystem—and even people within an organisation—to understand and act as if data belongs to people. Traditionally, governments and businesses are designed to control data to govern or to gain competitive advantage. The focus has seldom been on empowerment. So, when something designed on a different set of principles is introduced into the system, conflicts are inevitable. And they manifest in interesting ways.

The State of Aadhaar report showed one in three persons who tried to update their information found the process difficult, and one in five did not succeed. 4% of people currently have errors in the information on their Aadhaar; 15% have an error in their linked mobile phone number; an additional 39% have not linked a phone number at all.

While technology can resolve some trade-offs between convenience and security (using eKYC instead of photocopies of identity documents is an example), other trade-offs remain. You keep the door too wide, anyone can enter. Too narrow, and you might shut out even the owners. Besides, as the US Department of Justice prosecutor-turned-venture capitalist Katie Haun points out, “Sometimes, the earliest adopters of new technologies are criminal. Criminals are always looking for loopholes, or new ways to exploit systems.”

While the principles themselves have to be consistent, the system needs to constantly evolve to align itself with better principles. Over the last few years, Aadhaar has evolved in many ways. UIDAI introduced a biometric lock feature to allow users to activate Aadhaar only when there is a need. It allowed users to create temporary virtual IDs, allowing them to mask their Aadhaar numbers. It added facial biometric authentication to fingerprints in a fusion mode to reduce the chances of rejection.

#4 How do I effect systems change, not just a change in a specific segment?

The traditional way of attacking a problem, or capturing a market, is by narrowing it down. If you are in a business you are encouraged to go granular, identify a very specific segment, and solve for it. If you are in the social sector you are encouraged to pick up one specific cause—say, malnutrition, literacy, water, or sanitation—and solve it. It’s a good idea because it’s the opposite of boiling the ocean.

Purohit says, however, it’s not enough to think in terms of segments; think in terms of the larger system. A system change is needed to take people to a higher orbit. Changes in a single segment will not be enough because other factors will pull them back to the earlier equilibrium.

The challenge is in solving specific segments with their specific challenges, while not losing sight of the bigger picture.

The story of DigiLocker shows why context matters, and how that shapes the adoption and growth of technology and draws its boundaries.

To understand the promise of DigiLocker, we have to understand the idea of ‘traffic generation’. In the physical world, the term referred to induced demand: When you build a road, traffic quickly expands to congest it. As Robert Caro wrote in Power Broker, his biography of Robert Moses who pushed for a specific kind of infrastructural development in New York: “Watching Moses open the Triborough Bridge to ease congestion on the Queensborough Bridge, open the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge to ease congestion on the Triborough Bridge and then watching traffic counts on all three bridges mount until all three were as congested as one had been before, planners could hardly avoid the conclusion that ‘traffic generation’ was no longer a theory but a proven fact.”

It’s painful to get stuck in traffic on any day, but in case we do, it’s worth spending our time pondering over its equivalents in the digital world. YouTube didn’t merely play host to videos that were created anyway, it created a whole group of YouTubers who produced videos specifically for the platform. TikTok created TikTokers. Instagram created Instagrammers. Likewise, Slideshare didn’t merely cater to people who wanted to upload their existing decks. It also encouraged people to create decks and spread knowledge (or junk) via Slideshare. It’s a loop— platforms attract users, users post content, that content attracts more users, who in turn post more content.

Now, in India, getting government documents can be a harrowing experience, driven to a large extent by a lack of system capacity. It affects the poor even more. Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto Polar attributes poverty in large parts of the world to the fact that the poor don’t have titles to their property. In India, as the State of Aadhaar survey shows, millions of people didn’t even have a widely accepted identity document. An analysis of data on birth certificate showed that ‘India’s poor are also document poor’.

Digitisation can solve some of the problems related to the documents by reducing transaction costs. It can potentially enhance the system’s capacity to cater to a larger number of people.

Just like how new roads can generate more traffic and YouTube can generate more videos, DigiLocker, which enables sharing of government documents, can potentially induce supply of more digital documents.

However, it comes with its own problems.

When my colleague Charles Assisi and I were reporting on our book The Aadhaar Effect, Amit Ranjan, chief architect, DogiLocker, spent a few hours with us in Delhi to explain how the system works.

It’s not about technology, he told us. “It’s about how to get your job done. From outside, we think of government as a monolith, that there is a big boss sitting at the top of the hierarchy. He gets things done by passing an order, and then it finds its way down to the person who gets it done. But, what I learned from my time so far in government is that it’s more like an archipelago of 100 or 200 islands, each with its own king—who might not let you in. Even if you are in, there can be bottlenecks anywhere in the system. You can’t do anything about it. Sometimes, senior bureaucrats exert their authority when they spot a bottleneck. But I can’t do that.

“I have to work my way through the bureaucracy, the middle layer, the lower middle layer, the lower layer because that is what drives the government. It’s the bureaucrats who run the government,” he said.

The good news is that bureaucracy also attracts some of the best talent in the country and from inside the system they make things move.

In 2016, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) issued digital certificates to successful 12th standard students on the day the results were announced, allowing them to apply to universities straightaway. It used to take a few weeks earlier. In 2018, the government issued a notification to treat the digital documents as equivalent to physical documents. When Kerala was hit by floods, the DigiLocker system helped people get lost documents fast.

It’s not clear yet whether these early successes will create a virtuous cycle of people demanding digital documents from the government, and various government departments responding to it.

The bigger point, however, is this: to effect real change in people’s lives, making one part work better is not enough.

Nilekani says India Stack broadly comprises of three layers—and all three are important.

- The identity layer, comprising Aadhaar, eKYC and eSign which allows anyone to authenticate themselves digitally. Because it’s digital, one need not be physically present in a specific location to access a service. The rich take it for granted, but the poor don’t have that option.

- The payments layer, comprising UPI, Aadhaar Payments Bridge, and Aadhaar Enabled Payments Service, which allows users to transfer money, over a smartphone, feature phone, or through micro ATMs.

- The data layer, which comprises DigiLocker and DEPA, which allows users to share data securely.

This is the technology part. It also needs enabling regulations and laws. A company can have internal processes, but it also needs legislation to give a hard push, says a data auditor, citing the example of an IT services company which put in place a data protection policy more than ten years ago. But, employees started taking it seriously only after the EU passed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), he said.

In India, the personal data protection bill, which was recently approved by the cabinet, might give a much-needed nudge for the data layer. The bill recognises data portability as a right, imploring organisations to provide customer data in a structured, machine-readable format. It also recognises the idea of consent managers who will ‘gain, withdraw, review and manage (data owner’s) consent through an accessible, transparent and interoperable platform’—forming the legal basis for the technology across sectors.

Different countries have followed different approaches to protecting data. The US has mostly left it to technology from the private sector. Europe has tried to solve it using far-reaching legislation such as GDPR. India needs both.

Law alone is not enough. “It’s like taking a sword to a gunfight,” says Tanuj Bhojwani, a volunteer with think tank iSpirt, which is a pro bono partner in developing India Stack. It cannot be left with technology investments by the private sector alone as the risks of corporate surveillance get starker. India’s own response has been a techno-legal approach, treating digital infrastructure as a public good.

#5 How do I think long term, and still make it real for today?

Siddharth Shetty, a volunteer with iSpirt who has worked extensively on DEPA explained his team’s approach thus: “We take a long-term view of a problem. We look at how things should ideally be 10 or 20 years down the line in terms of financial inclusion or education or healthcare and then ask what needs to be in place for us as a society to achieve that. What kind of digital infrastructure should be there so that the benefits that go only to the top-end of the pyramid, reach everyone?”

This approach typically takes time. Build the APIs, standards and components. Convince government departments and businesses to use it, build applications on the top of it, tweak them, make it better. And then it starts yielding results.

To keep the problem real and immediate, Sharad Sharma, co-founder of iSpirt, says that they imagine a street vendor called Rajini, and ask themselves how will it help her.

Think of it as a version of MK Gandhi’s talisman. “Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you,” Gandhi wrote, “apply the following test. Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him. Will he gain anything by it? Will it restore him to control over his own life and destiny? In other words, will it lead to swaraj [self rule] for the hungry and spiritually starving millions? Then you will find your doubts and your self melt away."

In the case of Rajini, she is essentially a prisoner of her geography. She borrows money from a moneylender in the morning, buys goods and spends the rest of the day selling them at a margin, and finally repays the loan along with exorbitant interest. She is creditworthy, but her circle is small, limited to people she knows personally. The combination of identity, payments and data layer could potentially help her demonstrate her creditworthiness to the larger market, which will then induce lenders to compete with each other to finance her at lower rates of interest.

If it sounds like a stretch of the imagination, it need not be. This is exactly how the world of the rich and the privileged works. We trade information, money and goods choosing from a far bigger pool than our geography or cognitive abilities would let us do without digital technologies. The internet meant the death of distance for the rich. Treating digital infrastructure as a public good, even while respecting the individual ownership of data, can open those doors to a larger group of people.

The art of the start

However, just as how a startup is not a smaller version of a large organisation, providing services at scale, catering to a billion people, is not the same as catering to a million people. Opening these doors to a billion people also means exposing them to risks of digital technologies—fraud, security, privacy, badly designed applications.

Manish Sabharwal, chairman of staffing firm TeamLease says, “A person’s sophistication about India can be discerned by whether he talks about ‘what to do’ or ‘how to do’.” It applies to those who talk about designing for scale. India’s experiment with and experience of using tech to solve hard problems shows that exploring these questions might help in the journey from ‘know what’ to ‘know-how’.

In October, speaking at the Centre for Global Development in Washington, Nilekani stressed on the importance of minimalism and simplicity, and went on to add, “I think technology has great promise in development but doing it properly, doing it thoughtfully, doing it by strategically thinking of it as platforms that can start combining and creating innovation is very important to get the full bang for the buck.”

Earlier, he ended his presentation with a simpler piece of advice. “Start small. Start anywhere. Start today.”

Som Karamchetty on Feb 08, 2020 9:39 p.m. said

An excellent essay!

Government may spend taxpayer’s funds to start mega projects but the private sector should be involved in doing them as they are the entities that can benefit themselves and the country by taking the technology based systems and applications overseas and make money. It is possible that the government may own a stake in the intellectual property in the technology or artifacts and share in the gains of the private companies who take those products overseas. Thus, India’s taxpayers benefit from domestic as well as foreign penetration of technology products.

It is easy to follow the model by observing how the US companies get government funding, develop technologies, make and export products, and benefit the country.

namaji blog on Jan 14, 2020 6:39 p.m. said

A great article covering important questions from so many angles. I liked the organization into 5 probing questions.

I smell the Aadhaar Effect book in many places in the article. That one on MOSIP was news to me, the idea of an open-source platform for digital identify is a fantastic one, probably more powerful than Aadhaar itself.

1. The case of the door being open just right doesn't seem to be have been solved well for cases where the biometrics simply fail to authenticate, due to "technical" constraints, such as senior citizens, where age is a big issue. At these points of failure, Aadhaar (wrongly) gathers the perception of more inhuman than before, because the clerk is as helpless as the citizen. Implementation and exclusion are related, both need their top-10 lists of problems at the last mile user. Solving these can actually help the adoption of Aadhaar, because it raises faith and leads to more innovative solutions.

2. The government's own ability to use Aadhaar to its fullest potential needs examination. For example, with Aadhaar in place, it can integrate the technologies at its back end, to reduce the inconvenience to the citizen. Which it won't, and instead pass on the buck to the citizen, have him step into multiple offices to have his paper processed separately. For example, with most banking services core-banking enabled and most bank accounts Aadhaar-verified, the govt can put together the income profile of a citizen across banks and determine those whose income are below a certain limit and exclude those from TDS on interest. This it won't do, but the citizen will have to state it at each of the banks. Or they would put blanket limit amount for everyone. Such integration to enable profiling might already be in place for purposes of police, preventing money laundering or to deny services where they don't qualify, but it wouldn't be used for pro-actively delivering benefits for which they indeed qualify.

3. The citizen being the "owner" of the data is more like putting it poetically, rather than true ownership. To understand this, we have to ask the question in reverse. If the citizen refused to share data, would he be substantially inconvenienced or penalized from availing basic services ? If the receiver is a private entity such as e-commerce vendor, the choice still lies with the citizen. If it's the government, it is far less of a choice.