[Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay]

Note: This Week in Disruptive Tech brings to you five interesting stories that highlight a new development or offer an interesting perspective on technology and society. Plus, a curated set of links to understand how technology is shaping the future, here in India and across the world. If you want to get it delivered to your inbox every week, subscribe here.

The new avatars of the Turk

Towards the end of his brilliant book The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine (The machine, it turned out, had a human being making the moves), Tom Standage talks about how our views on technology swing easily from wide-eyed optimism to hyper-dismissive pessimism.

Standage writes:

“In the Turk's early career, the idea that it might have been a pure machine evidently did not seem entirely out of the question, since a number of quite learned observers were prepared to believe it. The late eighteenth century was a time when the possibilities offered by mechanical devices seemed limitless; to some people, a chess-playing machine would have seemed only slightly more miraculous than a steam engine or a power loom.

“By the end of the Turk's career, however, the idea that it might have been a genuine automaton seemed far less credible. Complex machines from railway engines to electric telegraphs were becoming a part of everyday life, and the people of the mid-nineteenth century considered themselves better able to evaluate what machines could and could not do. Once the Turk had been unmasked as a pseudoautomaton, rather than a genuine "self-moving machine," the idea of a genuine chess-playing machine suddenly seemed absurd. To drive the point home, in 1879 an automaton maker named Charles Godfrey Gumpel produced a "proof" that a chess-playing machine had been impossible all along and, furthermore, always would be.”

Gumpel was, of course, wrong, for eventually IBM built its Deep Blue, that managed to defeat one of the world’s best chess players, Garry Kasparov. (And made further progress since then.)

Technology is advancing so fast these days, that it will not take two centuries to move from a man inside a machine to a machine beating the man. However, we should still be wary of entrepreneurs who are passing off their Turks as Deep Blues.

Three years ago, John Carreyrou revealed that Theranos, which claimed to have developed a machine called Edison to disrupt blood testing, was actually using the traditional methods to test blood. The story was expanded into a book, and made into a documentary earlier this year.

This week The Wall Street Journal broke a story with a similar plot. India-based Engineer.ai, which claimed to use AI to build apps in a fraction of the time it takes humans, was in fact mostly using human developers.

“...Engineer.ai doesn’t use AI to assemble code for apps as it claims. They indicated that the company relies on human engineers in India and elsewhere to do most of that work, and that its AI claims are inflated even in light of the fake-it-till-you-make-it mentality common among tech startups.”

Separating the Turks from the Deep Blues is a much needed skill in the age of accelerated technological progress.

(Responding to the story, Engineer.ai CEO Sachin Duggal has posted a long response saying, “We’ve never claimed to automate software development, we have always said Human-Assisted AI was more accurate.”)

Dig Deeper

Blood, Sweat and Tears in Biotech — the Theranos Story (a review of Bad Blood), by Eric Topol | Nature

The Turk: Wolfgang von Kempelen's Fake Automaton Chess Player, by Susan Fourtané | Interesting Engineering

Scaling Mt Solar

Two experiments with solar roads—one from France and another from the Netherlands—point to two different answers.

In 2016, France opened its solar road with much fanfare. After three years, it looks like Murphy’s Law has been dancing on it all along. The idea behind the one kilometer stretch, embedded with photovoltaic cells, was to generate enough electricity to power the streetlights of a local town. But only half of it was generated, thanks to rotten leaves hindering the already sparse sunlight falling on the road. Besides, the roads were too noisy, that the speed of the vehicles had to be restricted to 70 kmph. Over time, panels splintered or came peeling off. By many measures, the project was a disaster.

The Netherlands, on the other hand, seems to have done well. According to Sola Road, a company that develops solar pavements, a cycle path generated more electricity than expected. It has listed out a few lessons from the pilot. That the top layer of the road is important. That you shouldn’t demand any behaviour change from either the cyclists or those who maintain the road. That you should keep experimenting and optimising. There is more here.

Getting the pilots right is the beginning of the story. Scaling up is the key. The huge difference in outcome between a cycle path and a car path underscores that.

Dig Deeper

Tesla Pitches a Solar Rental Program to Boost Its Renewable Energy Business | TechCrunch

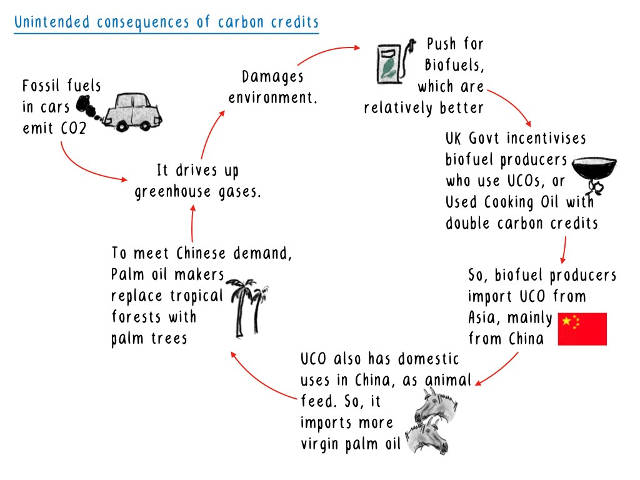

Biofuels’ second order impacts

BBC reports that “imports of a ‘green fuel’ source may be inadvertently increasing deforestation and the demand for new palm oil”.

[Graphic by NS Ramnath, based on the BBC article]

Dig Deeper

Implications of Imported Used Cooking Oil (UCO) As A Biodiesel Feedstock | NNFCC

Why Carbon Credits Don't Work, by Kevin Bullis | MIT Technology Review

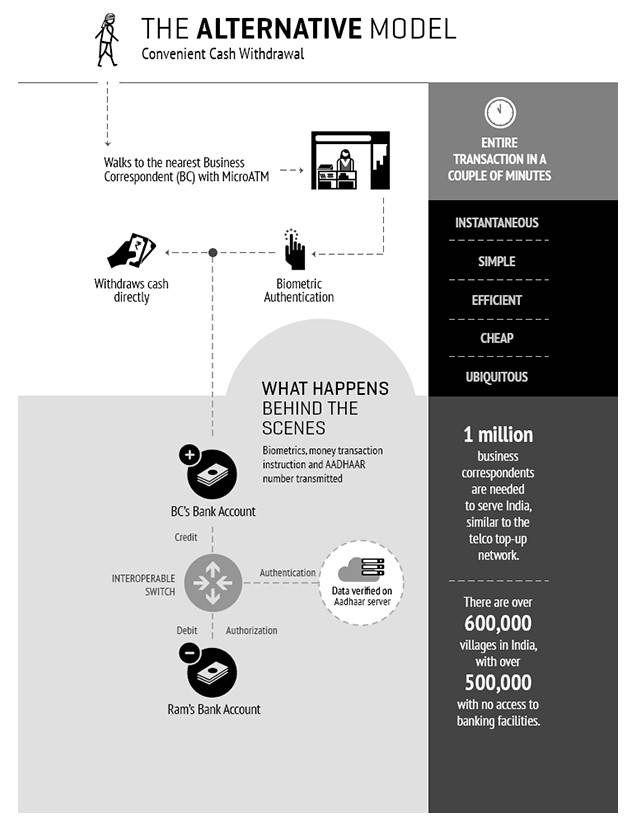

Reinventing the micro ATM

ARK Disrupt, a newsletter from ARK Invest, a fund focused exclusively on disruptive innovation, reports that Square received a patent for a technology that could turn its merchants into ATMs. “Cash App users already can use their Cash Cards, through Cash App debit cards, to withdraw cash from a network of ATMs, for which Square charges $2 per use. If a user receives $50 worth of direct deposits every month, however, Cash App scraps the fee. Now with the patented technology, Cash App users will need only a phone, not a physical card, to make withdrawals.”

If this sounds familiar to you, it’s because India has had this technology for some years now, thanks to Aadhaar and India Stack. My colleague Charles Assisi and I had a chance to try some of these devices in villages during our reporting for our book The Aadhaar Effect. It’s designed to be used without a card or phone—just with biometrics.

[From Rebooting India, by Nandan Nilekani and Viral Shah]

Dig Deeper

Micro ATMs a Big Hit in Rural India, Transactions in May Touch 33.5 million, by Ashwin Manikandan| Economic Times

Report of the High Level Committee on Deepening of Digital Payments | RBI

The parasite that got into a snail’s head

[Source: Gilles San Martin / Wikimedia]

You might have seen this gif on your Twitter timeline or on WhatsApp. It’s about a worm called Leucochloridium. In the words of Wired,

“It’s a parasitic worm that invades a snail's eyestalks, where it pulsates to imitate a caterpillar (in biology circles this is known as aggressive mimicry—an organism pretending to be another to lure prey or get itself eaten). The worm then mind-controls its host out into the open for hungry birds to pluck out its eyes. The worm breeds in the bird’s guts, releasing its eggs in the bird’s feces, which are happily eaten up by another snail to complete the whole bizarre life cycle.”

The story is worth remembering before we let AI into our heads, something that Elon Musk is attempting with his Neuralink.

In Financial Times, Susan Schneider, author of a forthcoming book on AI, warns against merging AI into human brains because AI might end up dominating our brains, and therefore us.

“We should be sceptical of any suggestion that humans can merge with AI. AI-based enhancements could still be used to supplement neural activity, but if they go as far as replacing normally functioning neural tissue, at some point they may end a person’s life.”

There’s a lot to learn from nature.

Dig Deeper

Neuralink and the Brain’s Magical Future, by Tim Urban | Wait but Why