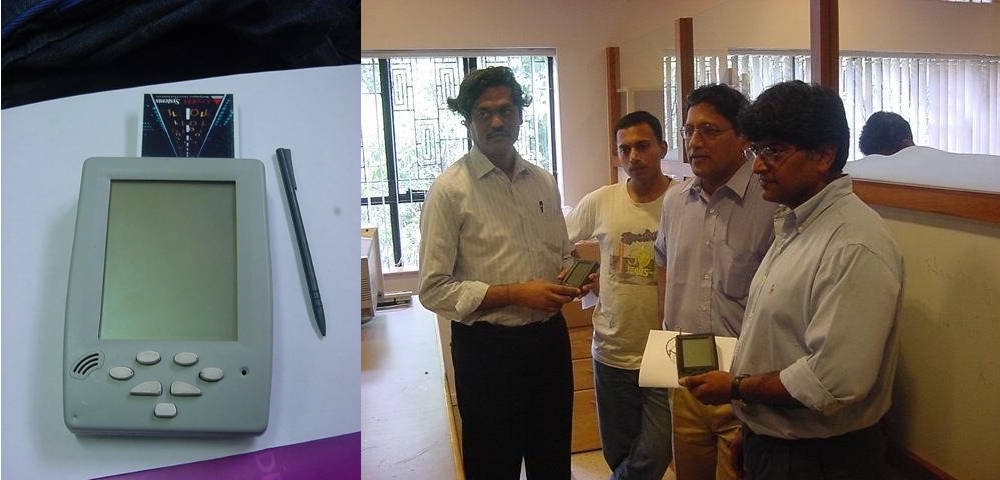

[The simputer and the core team behind the device. (From left) V Vinay, Ramesh Hariharan, Swami Manohar, and Vijay Chandru. Vinay and Chandru are holding Simputers. Photographs by www.simputer.org and V Vinay]

Towards the end of 2001, when the writers at The New York Times Magazine sat down to write about the year in ideas, there was one innovation that captured their imagination more than Apple’s PowerBook or Microsoft’s Windows XP. “This is computing as it would have looked if Gandhi had invented it, then used Steve Jobs for his ad campaign,” the newspaper wrote. It was referring to the Simputer, a handheld device designed out of Bengaluru.

This was six years before Apple would launch one of its most game changing products, iPhone. iPhone used a 3-axis accelerometer, the first time an accelerometer was incorporated in a phone. One of the basic applications of accelerometers in smartphones is that the screen is always displayed upright, whichever way you turn the phone. The accelerometer is now standard in smartphones. Not many know that the Simputer had an accelerometer in 2004! Not only that, it also had a handwritten annotation feature that was later popularised by the Samsung Galaxy Note launched in 2011.

For all these technological innovations, the Simputer didn’t turn out to be a commercial success, and its story holds a few important lessons for not only entrepreneurs and investors but also for policy makers. Its story from its spectacular launch to eventual fading out of public memory underlines the need for nurturing a capability to design and build from scratch an Indian electronic device for the global market. It also raises questions on whether India has developed expertise in marketing a new category of electronic devices, and if it has the capability in hardware manufacturing.

The Simputer was an easy to use handheld computing device targeted at the bottom of the pyramid semi-literate or illiterate user base. The “apps” envisaged for this segment were providing relevant information on commodity pricing, weather, money transfer, booking appointments with the healthcare centre, etc. The Simputer ran on a robust open source hardware and software platform to keep costs low, and keep it working in rugged environments. It was lightweight, thrifty on power consumption, easy to maintain, tolerant to heat, humidity, dust and vibrations, capable of good screen visibility both outdoor and indoor, and capable of delivering clear audio even in a noisy environment. The advanced applications for the Simputer included telephony, data access, and financial transactions.

While the Simputer was a success in demonstrating that Indians in India could conceptualise, design, develop, and produce a new category handheld device, three critical challenges ensured that it had only a limited commercial success. These were marketing a new technology category both to the bottom and top of the pyramid, paucity of risk funding for entrepreneurs, and absence of sophisticated hardware manufacturing in India.

No fortune at the bottom of the pyramid

The vision for the Simputer was a low-cost device, to help every Indian citizen—especially those at the bottom of the pyramid—irrespective of gender, language, physical handicap, geographical location, caste or creed, literate or illiterate, to access the information superhighway.

Did the focus on the bottom of the pyramid make the Simputer financially unviable? The utopian assumption was that every Indian village would require a Simputer that will be with a trustworthy person like a postman. Every adult will have a smartcard that contains personal information which would be inserted into the Simputer as required and access the various “apps”. The assumption was that the Central and state governments will be major customers of the Simputer to bootstrap their e-governance initiatives. However, this never materialised.

The focus on the bottom of the pyramid was probably ahead of its times. One of the dominant perception problems was the nagging question from the non-urban user segment: Why should we buy an “inferior” device that was not going to be sold in the city?

This was reinforced by the Simputer’s eventual hardware manufacturing partner from the public sector. While their executives shared the Simputer team’s vision of targeting the bottom of the pyramid, this did not percolate to the mid-level managers. They nudged the Simputer team to make changes in the design specs to target the urban customer as well. This meant adding features like a JavaScript-enabled internet browser, e-mail client, and MS Word and MS Excel compatible viewers. The internet browser had limited support for JavaScript, and users found it difficult to login to sites that used JavaScript. All these features had to be included on a platform that was meant for the bottom of the pyramid and was priced at about Rs 10,000 with a monochrome display. With all these features built into the Simputer, the performance was possibly not up to the mark for an urban customer.

In hindsight, one of the marketing opportunities was to sell the Simputer board as a low-cost standalone computer. This seems obvious in today’s context of standalone low-cost boards like Arduino and Raspberry Pi. Another marketing opportunity was to develop the software for the Simputer into an open source platform and an alternative to the existing Symbian OS and Palm OS—like Android. These marketing and business models that seem obvious today did not exist a decade and half ago.

There was a lot of visibility for the Simputer among leading media channels across the world. The New York Times Magazine called it the most important innovation in computer technology in 2001. Many other international publications like Time, Wired, Le Monde, The Guardian, BBC, and MIT Technology Review published articles on it. The standard computer science textbook used widely across the world, Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware/Software Interface by David Patterson and John Hennessy, also discussed the Simputer. This international visibility was not marketed enough to garner more funding for the Simputer.

A world without VCs

The four founding members of the Simputer team bootstrapped the project in their lab at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru in late 2000. Between 2001 and 2005, the team managed to raise Rs 2.5 crore, mostly from a dozen angel investors of Indian origin. They then raised a loan of Rs 2 crore from the Technology Development Board which was subsequently repaid in full. To put the fund raising in context, the Simputer project was comparable in scope to the iPaq project of Compaq which had a funding of an estimated $50 million.

In the early 2000s angel investors and venture capitalists (VCs) did not come in search of promising startups like they do today. There was no concept of exclusive funding for social impact. Today, there are startup funds exclusively focused on social sector startups. While Rs 4 crore was earmarked for marketing the Simputer by the public sector hardware manufacturing partner, a large part of it was never spent.

The government was the perfect large order customer for the Simputer. Though the Indian government liberally used Simputer in its advertising, there was little real commercial support in terms of an order. A funding of about Rs 50 crore would have seen the Simputer project through. This could have come in the form of a large order—for instance, 50,000 devices for use in e-governance programmes. The order would have been sufficient to prime the supply chain, and help the Simputer survive the initial years.

Make in India

While the marketing and funding challenges are related to the business model, the third is a more fundamental one in terms of India’s capability in hardware manufacturing. The first priority of the Simputer core team of IISc professors was to get the board up—V. Vinay used to write the software and Swami Manohar would burn it into the EPROM (Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory). Simputer purchased one StrongARM development board from the US—a microprocessor board used for prototyping. While the Simputer team had a commercial partner, things did not work out well between them and they split ways. Subsequently, a hardware manufacturing partner from the public sector was identified.

The first run for the Simputer was fixed at 10,000 units, and the inventory was bought from global suppliers. The hardware manufacturing partner did not budget for design iterations before finishing the first run. Being a public sector enterprise, the partner was bound by a cautious approach which placed financial prudence as paramount. Cost plus pricing was the norm, and planned losses in the first lot as a strategy to drive adoption was not an option at all. Even though solutions were identified for issues like the USB drawing more power when idle, any iterations to modify the hardware design was possible only after the first run.

The Simputer team had to make do with a sub-optimal solution of choosing a multi-national corporation (MNC) operating in India to manufacture the casing. This was a time when Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) hit Asia, and the ever cautious hardware manufacturing partner felt that there was a high likelihood for an order for casings to be quarantined in Taiwan or Hong Kong. And they took the less financially risky approach of using an MNC for manufacturing the casings in India. This proved to be a difficult job for the MNC, and the final product was not up to the mark due to limitations of their manufacturing technology.

Hardware: Where is it headed?

Where do we stand a decade and half after the Simputer project started? The challenges in funding are almost non-existent today. There is a well-developed ecosystem of angel investors and VCs, including those who focus on the social sector. While India has a vibrant supply of product management and marketing professionals including those with international experience in the domain of electronic consumer products, there is still very little experience in marketing a new category of technology products. To a large extent, challenges in marketing a new category of technology, creating an ecosystem, and the ability to change mindsets to accelerate adoption still persist. While global electronics supply chains are highly connected, Indian capabilities in hardware manufacturing are still a challenge. And this challenge is even more pronounced today.

According to a Niti Ayog report, India’s domestic hardware production in 2014-15 was about $32.5 billion, a miniscule 1.5% of global production. India’s domestic consumption of electronics in 2014-15 was about $63.6 billion, and about 50% of the demand is met by imports. Further, various research reports estimate the domestic consumption of electronics at about $400 billion by 2020, of which only $100 billion (about 25%) will be produced in India. To put the $300 billion of estimated electronics imports in perspective, India’s current forex reserves are about $360 billion. India has just embarked on a serious two-pronged strategy for electronics manufacturing that involves import substitution and an export orientation. It has not been an easy journey.

India needs to make rapid progress to overcome these challenges, and encourage many more audacious experiments like the Simputer. Some of them will go on to become commercial successes.

The rationale for reimagining computing devices to break the digital divide has only increased manifold in the recent past. The New York Times Magazine conveyed the message poignantly in its article on the Simputer: “Computation, however, is just a technology. In the hands of the planet’s majority populations, it may look a lot different.”

(The views are personal.)

Simputer: A brief history

1998—a quest for easy, universal access to the internet: It all started with the first BangaloreIT.com conference in 1998 where the “Bangalore Declaration on Information” discussed how information technology can be leveraged by a country like India to improve the lives of ordinary citizens.

The Bangalore Declaration highlighted the need for a simple access device to help an average Indian get on to the emerging information superhighway.

This lofty goal of “radical simplicity, universal access” was the basis of the Simputer—SIMple comPUTER or Simple Inexpensive Multi-lingual People’s CompUTER.

The use case and design of the Simputer was refined in the document “The Simputer: access device for the masses.” The Simputer was conceived as a device primarily used for information access, transactions, and communication.

The team: The core team were faculty from the Indian Institute of Science’s (IISc’s) computer science and automation department: Vijay Chandru, Ramesh Hariharan, Swami Manohar, and V Vinay.

How it all came together: The Simputer Trust was formed to hold a Simputer General Purpose License that was drafted to keep the software and hardware open. The members of the Simputer Trust were the four faculty members from IISc, three members from electronics product company Ncore Technology, and Rahul Matthan, a lawyer at Trilegal.

Picopeta Simputers was a company started in 2001 by the four IISc faculty members with a Simputer license from the Trust. At its peak, Picopeta Simputers had about 30 engineers, many of whom were IISc alumni.

The design: The Simputer was “a Net-linked, radically simple portable computer, intended to bring the computer revolution to the third world,” in the words of a New York Times Magazine feature in 2001.

What the Simputer could do: An easy to use interface was critical for its wide adoption in rural areas.

So, one could use a touch panel with a plastic stylus as an input method. And it could read out text from a website or email, thanks to its text-to-speech translator, Dhvani, which could handle Indian languages like Hindi and Kannada.

It had a smartcard connector. It envisaged the use of individual smartcards to access the “apps” so that one community Simputer could be shared by many.

Since cellphone service was expensive in India in the late 1990s, the device had an RJ-11 telephone jack for a wired internet connection.

It was also the first handheld to have a USB master.

One of the most important design elements was a powerful annotation feature. A user could annotate in any window, be it a web page or audio player. And the user could share annotations via email.

An open source model: Two aspects related to the design are worth mentioning. One, the Simputer team did not want to get locked-in with the forced obsolescence strategy of the dominant chip and software vendors. Two, they also decided that the hardware and software design will be open to public. Since it takes time to recoup investments in hardware, the SGPL provided a one year window for the designer and manufacturer before the entire hardware design had to be made public. This was probably the first open-stack design in India.

Ready for market: By 2004, when the Simputer was ready for commercialisation, it also had about 100 apps like Geogebra (an open source educational app for geometry and math), chess, etc. that could be ported. It is important to note that the Simputer was designed to be a handheld computer, and not just an organizer. The overall cost of a Simputer at reasonable volumes was estimated at slightly under Rs 10,000 for one with a monochrome screen. The Simputer also had a model with a colour screen that was priced at about Rs 20,000.

Jay Srinivasan on Jan 24, 2017 4:42 a.m. said

A nice, comprehensive, perspective on Simputer. I have also read the comments and, while they hit many points, we may have to search for other reasons as well. Permit me to paint the landscape. I am an entrepreneur who is currently involved in a hardware-software venture. I am not an engineer and certainly do not have the "smarts" of Simputer's founders (I do know both Vijay and Swami). Simputer, in many ways, was a groundbreaking venture that, even as it failed, influenced many new entrepreneurs. My background is in the social sciences; I graduated from JNU and from a couple schools in the US, where I was employed at several tech companies for over 15 years, with a long stint in the SF bay area. I have been back in India for about a decade with half that time spent as an entrepreneur running my own venture.

What I have thus far seen is that most Indian entrepreneurs are colored, from the get-go, with a mindset to emphasize their relevance. This existential problem comes from influences from various quarters - the media which tends to go hyper on an activist mode with panelists who are drawn from the NGO, activist, left-intellectual and who are either against free markets or do not understand it; the academic community who generally - in my experience having actively sought faculty collaborations and partnerships - have zero appreciation of entrepreneurship and startups and the exigencies and constraints that have to be managed and their institutional employers preferring a mild toleration of entrepreneurship while they focus on esoteric academic research; social cues and peer pressures that make it difficult to entertain good talent who prefer brand visibility employment even if they are monotonous and contribute little to their career growth; and preference, especially among techies in India, to join the management cadre and eschew engineering after just a few years - this is most apparent in the IT services industry. These are real problems.

What do I mean by "existential problems and a mindset to emphasize their relevance"? Simply that we are drilled at all levels - and this becomes even more difficult in fist-generation entrepreneurs from middle class backgrounds - to economic and social compulsions as dictated in our various Nehruvian plans, our polity, and therefore the respectability to acknowledge these. Look around and you will see that the successful India startups have no hangups about whom they are targeting and little embarrassed by their positioning. The failed ones, on the other hand, are the ones that talk about "bottom of the pyramid" and use words like the poor and inclusion. Don't get me wrong, we need to address these as a society, but ask yourself: if successive governments have failed at this for a very long time, NGOs despite their numbers have only a marginal impact, and intellectuals only criticize and offer no solutions, can entrepreneurs do any better? If you are a for-profit venture and constrained for funds, you are better off pursuing hard-nosed revenue growth with profitability than pie-in-the-sky social objectives.

Would it not be better to pursue growth with profitability in the initial years and then undertake R&D to offer innovative solutions to solve some problem at the bottom of the pyramid? To me, that would seem a very sane and realistic. But startups are forced to reject such thinking, even if they are inclined to, by lenders. Long before startups approach VCs they try out the various government schemes. All of them evaluate the startup on "social objectives" to approve a grant or other. These schemes are constructed by bureaucrats who have little appreciation of target markets, product development, design iteration, prototyping, burn rate, customer acquisition, or long-term profitability.

That, in short, is what handicaps a good many startups in India: a confusion in purpose that is reflected in bad business plans.

Dayasindhu N on Jan 17, 2017 6:39 a.m. said

Thanks for taking time to respond. We need to learn from the Simputer experiment. And take note of the exogenous and endogenous factors that increase or decrease the propensity for a useful technology to achieve a critical mass in adoption.

Let the Simputer inspire many more such audacious experiments in India. And hopefully some will succeed. And the RIPs and baby-showers become recursive!

Arun Muthirulan on Jan 16, 2017 7:43 p.m. said

A very timely and well researched article given the emphasis on and the urgent need for rapid scaling up of electronics manufacturing in India.

Having spent the last decade and half looking at several innovative products and services from international ecosystems and their journeys towards market success or failure, I think we need a nuanced approach to look at the trajectory of an innovative product such as the Simputer.

New products or services enabled by innovation in science and technology go through three transformations - concept to prototype, prototype to early product and early to mass market product. In these transformation, several essential elements for commercial success get validated

concept to prototype : availability of the right technologies and the expertise to create a working prototype;

prototype to early product: a functional product sold to "charter" customers with a viable business model;

early to mass market product: ability to manufacture product at scale and successfully execute the go-to-market plan.

Our work, which Dr Vyakarnam refers to in his comments below, looked at customer adoption numbers and rates of more than 300 international businesses across multiple sectors between 1995-2015. This review identified 3 chasms that exist between the three stage transformations. A "Chasm" is defined as that part of the journey where there is no customer growth. We found that of the three, Chasm II is the most challenging and takes longest to cross. It is the point at which the product or service needs to make progress on technology, proposition, market and customers to be of value to the early or "Charter" customers while also proving the business model. Here charter customers are defined as those interested in the core proposition due to immediate need and are willing to work with a early version of the product or service.

The Simputer had tremendous success when crossing Chasm I, note the glowing and positive coverage in global and local media and even by a respected textbook, even when it was a prototype product. However, successful crossing of Chasm I doesn't guarantee subsequent success in the commercialisation trajectory. Simputer illustrates this in its struggles to break into the charter customer territory, basically the Chasm II, with a clear proposition that addresses specific customer needs at the right price point for the business model to be viable.

While several other points can be made about technology vs marketing, hardware vs software the role of ecosystems, funding etc., all of which nevertheless are of varying significance, the essence of this story is the importance of selling the early product to enough customers and prove that the business model works.

More broadly, the legacy of the Simputer is the inspiration it provided and the enthusiasm it helped to generate to foster a can-do attitude, which we need now to address the impending electronics manufacturing challenge in India.

Shailendra Vyakarnam on Jan 16, 2017 5:20 p.m. said

Too much i being made of the Simputer as a failed enterprise. Around the same time the Apple newton bombed as did a Cambridge (UK) company called Active Book Company. And so many other innovations fail after their prototype phase for a myriad of reasons. I have been living and working in Cambridge for the past 20 years and have seen the successes and the failures over that time in hardware, software, lifescience and all manner of other technologies. If there is a common thread to why some technologies do not make it - they are of course management - not whether or not they are smart - but simply the chance that the wrong combinations of talent are in the driving at any given time. Market and customers not being interested because the team has not clearly identified what problem it is trying to solve and therefore not having a clear value proposition. The manufacturing ecosystem (in the Simputer case) not being able to cope in India is a minor headache in my view - as any "business house" could solve that by sourcing from China.

The Simputer was an ideology rather than a product. I have met Manohar and Vijay a few times. They are hugely to be respected for sticking their necks out at a time when academics going into business was frowned upon

heir legacy is perhaps not so much that the device did not get taken up - bearing in mind that others also fell over at that time. Their legacy is being role models of "can do" in Indian high tech.

Nokia was cited in one o the comments as an exemplar of rural marketing. Indeed they were. and where are they now?

A more detailed review and understanding of how science and technology goes to market will be forthcoming in a new book by Phadke and Vyakarnam. Camels, Tigers and Unicorns: Rethinking science and technology innovation. Our fellow researcher Arun Muthirulan and I have been in communication over this article and he may also add his comments.

Dayasindhu N on Jan 14, 2017 5:25 a.m. said

Thanks for taking the time to respond. You have raised some interesting points. I’m adding a few more.

Hardware: The focus of the Simputer was on building a systems capability – design and production of a new category computing device. And not chip design or electronic sub-component design and manufacture. The Simputer designed its board by integrating novel components like an accelerometer, a USB master in the early 2000s. A mention in David Patterson and John Hennessy in their text book - a “standard” across the world - indicates that there was something unique about the Simputer’s hardware architecture.

Software: Initially, the Simputer had only software “apps” that focused on the bottom of the pyramid. As I mention, the team was nudged by the manufacturer to make software for the urban user as well. The hardware design was not enhanced with the addition of software to keep costs down. And this did affect performance. The urban users who used it as a PDA are probably not the best judges of the Simputer’s software. The best judge of the software capability would have been the original intended users. And with about 100 “apps” I don’t think it is right for us to say software was neglected.

Mobile phones: A bit of context on Indian telecom in the cusp of the 20th and 21st century. India still had more landlines than mobile phones. Mobile phones did not connect to the Internet, and this was done via. a dialup modem. A Nokia phone without any data capability was priced about INR 4000 to 5000 in that era. And the mobile telephony charges were higher (and as a percentage of per capita income) than what it is today. But more important, the idea was not to sell an individual Simputer to every Indian in a village. What was envisaged was a community model - one Simputer for a village. And the Simputer could connect to the Internet via a telephone to upload and download data. By the turn of the last century every post office had a phone and most major villages in India had a PCO. Even today, surprising as it may seem, 70% of Indian mobile phone users still use a feature phone. I’m not sure if we can generalize that Indian users always demand the high-end devices.

Social impact funding: While VCs and PE players at the turn of the were funding traditional IT services and new age services like ecommerce (including services like designing websites), there was little money for social impact funding including for products like the Simputer. There was little risk appetite for such investments for the social sector in the early 2000s. Things have changed today with funds focused on this sector.

Lastly, the Simputer founding team wanted to provide meaningful benefits of computers and Internet in an affordable way to Indians at the bottom of the pyramid. The Simputer as a device was part of this objective. They were not competing with computers, laptops, mobile phones targeted at richer Indians at that point in time.

I was hoping the analogy be the phoenix. Let the Simputer inspire many more such audacious experiments in India. And hopefully some will succeed. And the RIPs and baby-showers become recursive!

Srini Bala on Jan 13, 2017 5:14 p.m. said

This is an interesting take on Indian innovation with a specific case study of Simputer, but with due respect, I think the article gets it wrong. I don't seem to agree with any of the conclusions drawn here.

Allow me to explain:

As a technology reporter in Bangalore around the turn of the century, I covered the story of Simputer from its concept to its launch and eventual failure. Over five years, I would have had about 100 conversations with its founders, especially Mr. Swami Manohar. I have always had huge respect for the founders' commitment to the product and their ambition to bring social change through technology. I took immense pride in my stories on Simputer.

Yet, I think the product failed not because of the reasons enumerated above. I think it was an entrepreneurial failure. The technologically brilliant founders failed as entrepreneurs. That says nothing about whether India can succeed with an innovative tech product or not.

First of all, the innovation in Simputer was a modest one. It was a product merely assembled from off-the-shelf components. None of the hardware was developed by the founding team, but bought. All its features pre-existed in the market. So, I wouldn't praise Simputer's founders for its accelerometer or the stylus or its form factor.

Marketing is not a skill that can convert an unsellable product into revenues. To gauge the marketing skills of any founding team, we have to first see how good the product is. The Simputer failed on that first hurdle itself, leave no room to judge whether the founding team could have marketed it well or not.

I got my head around this idea when I happened to stop Mr Azim Premji of Wipro at the door after a press conference and ask him about Simputer. I knew that Mr. Premji had been approached for a potential participation in the Simputer project and he had not agreed to it.

When pressed about his decision, Mr. Premji said the hardware part of Simputer has nothing to write home about. It had been put together with off-the-shelf components and he didn't see any investible value on the hardware side.

A rough and approximate recollection of the quote he gave me then:

"The trick with Simputer is really in the software, not the hardware. It has to have applications that are relevant for the target segment and those have to be killer applications. If you have such software, we can look at investing in it."

I think the techie founders focused too much on Simputer being a piece of hardware and didn't quite deliver on the applications side. I have not used the Simputer myself, but I have heard people say that the software was not really "killer."

Further, I don't agree with the supposition that "bottom of the pyramid" marketing was ahead of its time. Around the same time, a company called Nokia was going to the "bottom of the pyramid" and was trying to convince them they needed a phone.

That was the time when a phone was considered a cost centre by small-town households and an unthinkable luxury by the rural population. But Nokia did convince the "bottom of the pyramid" that they needed a phone. And here we are, in 2016, when the poorest of the poor are using computers aka smartphones that are much more powerful than Simputer.

Nokia succeeded just around the time Simputer failed. That was also the time when computing was taking small towns by storm. Every month, desktop and laptop sales were zooming. We have not reached the tech ubiquity we see today all of a sudden. The early steps of that revolution were taken around the time Simputer was failing to make itself heard.

I think the "bottom of the pyramid" has always been a viable market if your product was absolutely the right one for it. Simputer fell short.

About the opportunity to sell the Simputer board as a low-cost standalone computer or the software as a platform, I don't think the technological brilliance of Simputer was anywhere close to achieving that. That was a completely different route to take and required thousands of man-hours of technological brainstorming to achieve that. There was talk, then, of developing India's own operating system and the founders of Simputer were not going that route. They wanted to solve a different problem and had different capabilities.

And then comes the vexed question of funding. I am surprised that the writer says venture capitalists did not flock to start-ups like they do today. The reverse is the truth. Today, VCs and angel investors may have a lot more money, but they are also more prudent and have more exacting standards before deciding to invest. Those days, VCs behaved like they had been cursed to spend a billion dollars before breakfast or a parrot which contained their life would get its neck wrung.

Just when Simputer was struggling to raise money, I also met entrepreneurs who were struggling to meet all the VCs who wanted to invest in their new ventures. Just one example: There was a gentleman called Pradeep Kar. Remember Microland, PlanetAsia, Indya.com, ITSpace. He could raise money without asking. So to say that VCs funding wasn't available then is simply wrong.

Nobody wanted to invest in Simputer because the functionality of the product didn't excite them. For us, in the media, it was a good story because of the "bottom of the pyramid" angle. But for hard-nosed investors, the product didn't offer a compelling argument.

I remember attending the launch with great expectations because I had never seen a prototype before and was excited as hell. I remember Mr. Manohar saying the product had changed from the initial concept. His words, approximately, were: "we have even raised the price of the product so that the rich can afford it."

I was shocked to see that the product was less capable than previously thought, and more expensive than the promised price point.

That only sent out the message that the techie founders were confused: they were not clear about their target audience, gave up their commitment to the promised price threshold, and were trying to please any and every segment of the market, hoping one of them would accept it. Obviously, the product was bound to fail.

There were multiple reasons why Simputer failed despite the admirable social impact it had on the psyche of Indian consumers and the extraordinary dedication of its founders. But if you have to distil all that into one reason and sum up Simputer's failure, it is this:

The founders of Simputer wanted to solve the problem of computers selling at Rs. 40,000, a price point unaffordable to most Indians. So they tried to build a Rs. 10,000 computer and eventually delivered a Rs. 14,000 computer.

But the market was not looking for a Rs. 14,000 computer. It went in the other direction. Simputer's rivals, the big desktop and laptop manufacturers didn't bring down the price. Instead, they increased the processing power and memory of their Rs. 40,000 computers.

India's computer market, including the "bottom of the pyramid," chose the Rs. 40,000 computers that were becoming more powerful every month, than a Rs.14,000 computer that was static and had little to recommend apart from the price point.

And oh, the customers used that Rs. 14,000 to buy Nokia phones.

RIP Simputer. It was like Marcus Brutus of the Roman Republic. He failed in his own ambition to protect the republic and died a deserving death. But it was on his grave that a greater Rome emerged. It was from his mistakes that others learned how to do it properly.

Srini Bala on Jan 13, 2017 5:06 p.m. said

This is an interesting take on Indian innovation with a specific case study of Simputer, but with due respect, I think the article gets it wrong. I don't seem to agree with any of the conclusions drawn here.

Allow me to explain:

As a technology reporter in Bangalore around the turn of the century, I covered the story of Simputer from its concept to its launch and eventual failure. Over five years, I would have had about 100 conversations with its founders, especially Mr. Swami Manohar. I have always had huge respect for the founders' commitment to the product and their ambition to bring social change through technology. I took immense pride in my stories on Simputer.

Yet, I think the product failed not because of the reasons enumerated above. I think it was an entrepreneurial failure. The technologically brilliant founders failed as entrepreneurs. That says nothing about whether India can succeed with an innovative tech product or not.

First of all, the innovation in Simputer was a modest one. It was a product merely assembled for off-the-shelf components. None of the hardware was developed by the founding team, but bought. All its features pre-existed in the market. So, I wouldn't praise Simputer's founders for its accelerometer or the stylus or its form factor.

Marketing is not a skill that can convert an unsellable product into revenues. To gauge the marketing skills of any founding team, we have to first see how good the product is. The Simputer failed on that first hurdle itself, leave no room to judge whether the founding team could have marketed it well or not.

I got my head around this idea when I happened to stop Mr Azim Premji of Wipro at the door after a press conference and ask him about Simputer. I knew that Mr. Premji had been approached for a potential participation in the Simputer project and he had not agreed to it.

When pressed about his decision, Mr. Premji said the hardware part of Simputer has nothing to write home about. It had been put together with off-the-shelf components and he didn't see any investible value on the hardware side.

A rough and approximate recollection of the quote he gave me then:

"The trick with Simputer is really in the software, not the hardware. It has to have applications that are relevant for the target segment and those have to be killer applications. If you have such software, we can look at investing in it."

I think the techie founders focused too much on Simputer being a piece of hardware and didn't quite deliver on the applications side. I have not used the Simputer myself, but I have heard people say that the software was not really "killer."

Further, I don't agree with the supposition that "bottom of the pyramid" marketing was not ahead of its time. Around the same time, a company called Nokia was going to the "bottom of the pyramid" and was trying to convince them they needed a phone.

That was the time when a phone was considered a cost centre by small-town households and an unthinkable luxury by the rural population. But Nokia did convince the "bottom of the pyramid" that they needed a phone. And here we are, in 2016, when the poorest of the poor are using computers aka smartphones that are much more powerful than Simputer.

Nokia succeeded just around the time Simputer failed. That was also the time when computing was taking small towns by storm. Every month, desktop and laptop sales were zooming. We have not reached the tech ubiquity we see today all of a sudden. The early steps of that revolution were taken around the time Simputer was failing to make itself heard.

I think the "bottom of the pyramid" has always been a viable market if your product was absolutely the right one for it. Simputer fell short.

About the opportunity to sell the Simputer board as a low-cost standalone computer or the software as a platform, I don't think the technological brilliance of Simputer was anywhere close to achieving that. That was a completely different route to take and required thousands of man-hours of technological brainstorming to achieve that. There was talk, then, of developing India's own operating system and the founders of Simputer were not going that route. They wanted to solve a different problem and had different capabilities.

And then comes the vexed question of funding. I am surprised that the writer says venture capitalists did not flock to start-ups like they do today. The reverse is the truth. Today, VCs and angel investors may have a lot more money, but they are also more prudent and have more exacting standards before deciding to invest. Those days, VCs behaved like they had been cursed to spend a billion dollars before breakfast or a parrot which contained their life would get its neck wrung.

Just when Simputer was struggling to raise money, I also met entrepreneurs who were struggling to meet all the VCs who wanted to invest in their new ventures. Just one example: There was a gentleman called Pradeep Kar. Remember Microland, PlanetAsia, Indya.com, ITSpace. He could raise money without asking. So to say that VCs funding wasn't available then is simply wrong.

Nobody wanted to invest in Simputer because the functionality of the product didn't excite them. For us, in the media, it was a good story because of the "bottom of the pyramid" angle. But for hard-nosed investors, the product didn't offer a compelling argument.

I remember attending the launch with great expectations because I had never seen a prototype before and was excited as hell. I remember Mr. Manohar saying the product had changed from the initial concept. His words, approximately, were: "we have even raised the price of the product so that the rich can afford it."

I was shocked to see that the product was less capable than previously thought, and more expensive than the promised price point.

That only sent out the message that the techie founders were confused: they were not clear about their target audience, gave up their commitment to the promised price threshold, and were trying to please any and every segment of the market, hoping one of them would accept it. Obviously, the product was bound to fail.

There were multiple reasons why Simputer failed despite the admirable social impact it had on the psyche of Indian consumers and the extraordinary dedication of its founders. But if you have to distil all that into one reason and sum up Simputer's failure, it is this:

The founders of Simputer wanted to solve the problem of computers selling at Rs. 40,000, a price point unavoidable to most Indians. So they tried to build a Rs. 10,000 computer and eventually delivered a Rs. 14,000 computer.

But the market was not looking for a Rs. 14,000 computer. It went in the other direction. Simputer's rivals, the big desktop and laptop manufacturers didn't bring down the price. Instead, they increased the processing power and memory of their Rs. 40,000 computers.

India's computer market, including the "bottom of the pyramid," chose the Rs. 40,000 computers that were becoming more powerful every month, than a Rs.14,000 computer that was static and had little to recommend apart from the price point.

And oh, the customers used that Rs. 14,000 to buy Nokia phones.

RIP Simputer. It was like Marcus Brutus of the Roman Republic. He failed in his own ambition to protect the republic and died a deserving death. But it was on his grave that a greater Rome emerged. It was from his mistakes that others learned how to do it properly.