[Photograph KFC at Shezei by TianyinLee under Creative Commons]

By: Li Hui

It was a bitter cold day in November 1987. Scores of Beijingers braved the winter chill and patiently waited in a 50 meter long queue in the bustling commercial zone of Qianmen. They were here for their first bite of Colonel Sanders’ legendary fried chicken.

That first KFC in China sold 2,200 buckets of fried chicken and made RMB 83,000 on its opening day alone, a huge sum given that monthly salaries averaged at RMB 120-130 in those days.

Very soon KFC became a rage in China. It rolled out 400 restaurants across the country by 2000, becoming the first restaurant chain to do achieve that scale. In 2015, China had a total of 4,889 KFC restaurants.

Given the average income levels in China of those days, eating at KFC was a luxury, but because the brand was seen as aspirational, it thrived and grew. For the 85 hou and the 90 hou (terms that describe those born after 1985 and in the 90s) who grew up in Beijing, one of the most unforgettable memories of their childhood is of being rewarded with a meal at KFC for getting good grades or wining a singing contest. KFC was considered so cool that it even set the 1st grader fashion trend in the late 90s: if a kid did not possess a blue, yellow and red school bag (which came free with a KFC Kid’s Meal), he or she wasn’t considered trendy by his or her classmates.

In some ways, KFC laid the foundations for the fast food industry in China. It created a category where none existed. McDonald’s followed three years later. In 1990 KFC’s parent company Yum Brands introduced Pizza Hut in China which leveraged the idea of ‘casual dining’. Today Pizza Hut boasts of 1,421 outlets across the country. KFC also inspired the emergence of domestic fast food chains.

It’s been a long journey in China since then for the Louisville, Kentucky-headquartered Yum—and much has changed.

The Good Old Days

China worked like a dream for Yum. In 2010 China became Yum’s largest market in terms of profits globally. During the early years, both KFC and Pizza Hut (1,100-plus restaurants) experienced explosive growth in China. Things were so good that Yum even ventured into uncharted territory: a western brand offering Chinese food to Chinese customers. In 2005, Yum launched East Dawning, a sub-brand offering Chinese cuisine. More recently in 2011, Yum acquired Chinese hot pot restaurant chain Little Sheep which already had a good reputation in the market. In all, Yum operates 6,867 restaurants in China, second only to its home market of the US.

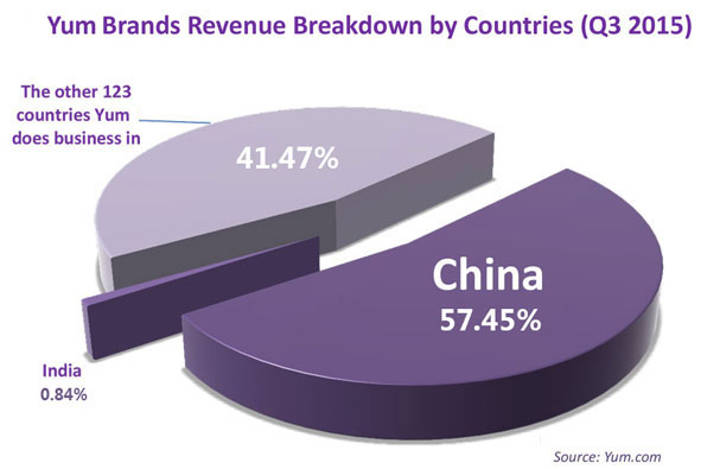

Yum Brands’ operating profit in China consistently maintained an enviable double-digit growth rate for several years. In the third quarter of 2015, 57% of Yum Brands’ overall revenues came from its China division.

Yum’s success in China became a case study in business schools around the world. It offered valuable lessons to MNCs wanting to get their China strategy right.

There are several reasons why Yum did so well in China. For one, it was different. Back then, Western-style fast food restaurants were a novelty for most Chinese consumers and the rapid pace of expansion of Yum restaurants helped them establish a strong foothold, says Laurel Gu, Research Manager from Mintel Group. “It was about the restaurant, the atmosphere, and the Chinese consumers wanting to get a taste of Western life and the way they eat,” says Michael Zakkour, co-author of China's Super Consumers and Vice President, Tompkins International.

Yum, unlike several western restaurant chains, also made painstaking efforts to localize its offering. Instead of transplanting executives from the head office, for the China operations Yum hired people who understood the Chinese culture better. The then CEO Sam Su was from Taiwan.

Yum took the time and effort to understand the Chinese culture and local Chinese taste, says Zakkour. “They started out with cultural relevance: that chicken is a huge part of every Chinese’s diet. They took two pieces of the culture, the natural taste of chicken on the bone and put that in the style of a Western fast food restaurant. They sprinkled the menu with local specialties and became an instant hit.”

They paid extensive attention to staff management and training and they also tied up with Chinese state-owned partners and fostered a good connection with local governments, adds Sophie Yang, Senior Lecturer in Marketing at Coventry University who has studied Yum. As any MNC will tell you, guanxi, or the art of building good connections, is a must for doing business in China.

There were two other factors that appealed to Chinese consumers. Standardization ensured that there were no nasty surprises: the fried chicken in Beijing tasted exactly the same as the one in Louisville. “Every link in the production process is standardized. Their ingredients are from the same source and the staff is trained in the same way,” says Bing Jing, Professor of Marketing at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. This was a new thing in China. Additionally, there was the added factor of convenience: especially for busy office-goers who don’t have a lot of time for lunch.

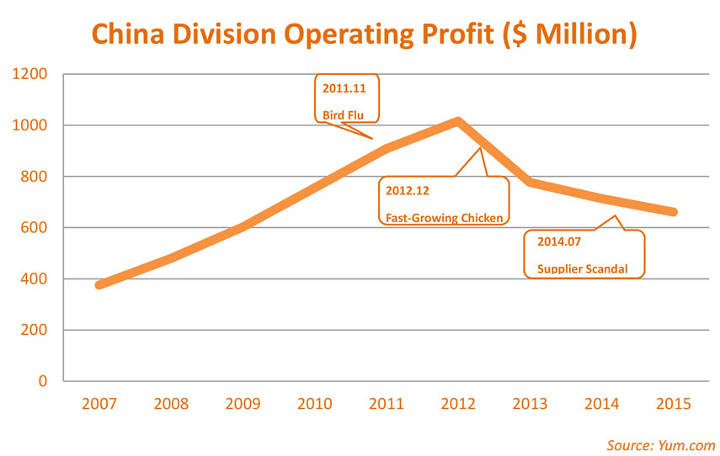

The Tide Turns

Yum hit a roadblock just when its growth momentum was at its strongest. December 2012 marked a turning point in Yum’s China run. State-owned broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) reported that Yum’s poultry supplier fed chicken with antibiotics to shorten the growth cycle to 45 days. This was just the beginning of a series of food safety scandals. In 2014, KFC’s supplier, the OSI Group’s plant in Shanghai was accused of allegedly re-processing expired meat and using low-quality raw materials in its production. There were outright bizarre allegations recently that Yum was using genetically-modified chicken, specifically those with six wings and eight legs. To add insult to injury, digitally altered photos of chickens were circulated on social media to make the rumor look real. Posts containing photos of the monster-like chickens were read over 100,000 times on WeChat, a popular social media platform. In May 2015, KFC announced that it would sue the three companies which operated the WeChat accounts that created the misleading posts.

Says Zakkour, “Most of [these scandals] are not the company’s fault, but you know how these things work: they print it on the whole front page and make the correction a week later on the [bottom] of the last page.”

These scandals spooked customers and hit Yum hard. Bouncing back has been tough. Part of the reason also is that KFC rode on its initial wave of popularity for way too long and didn’t do enough to refresh its image or offering. As a result market fatigue has set in. “No brand, idea or product can stay fresh forever. It’s part of a product lifecycle,” says Zakkour.

When Yum came to China, dining in a Western style restaurant was a novelty. Today such restaurants are commonplace, Chinese consumers are more sophisticated and exposed to the world. Quite clearly, Yum had fallen into the complacency trap. Says Zakkour, “I think they stopped innovating and became complacent. They had so much success that they allowed Pizza Hut and KFC to stagnate. They did not adjust to increased sophistication and changing tastes among Chinese diners.”

There’s yet another factor that has worked against Yum. From 1987, till now the competitive landscape has changed. While Yum is still the market leader, others are catching up fast. McDonald’s, which entered China three years after KFC, has been a pretty aggressive rival. Then there’s Burger King which despite a much smaller footprint and marketshare still takes a piece of the pie. Even Pizza Hut has to contend with rivals like Papa Johns and smaller chains.

If competition from Western companies wasn’t enough, there are also local fast food brands to contend with. Local brands like Real Kungfu and Yonghe King are acing the game in Chinese fast food, eating into the marketshare of Western fast food companies. Says Mintel’s Gu, “The mass market still prefers local cuisine. According to a survey we conducted, over 50% of the respondents say that they prefer Chinese fast food.”

In lower-tier Chinese cities especially, there are copycats too. KFC, for instance, has been blatantly copied by a chain that calls itself CSC (short for ‘Country-Style Chicken’, a company listed on the NASDAQ). Like KFC, CSC sells fried chicken and French fries (much cheaper of course), along with a variety of Chinese dishes.

Yum is also an unintended casualty of the boom in China’s Online to Offline (O2O) sector. Before online ordering platforms like Meituan and Baidu Waimai emerged, fast food chains like Yum and McDonalds enjoyed a “monopoly” in the food delivery business in China. Several years back, they were the only restaurant chains that delivered so if you wanted home delivery, you were pretty much stuck with them. “Before O2O [exploded], one of the [key] features of fast food restaurant chains was convenience. KFC, McDonald’s and Pizza Hut dominated the food delivery market back then,” explains CKGSB professor Bing Jing. But now O2O offers customers a wider range of choices for delivery with one platform, like Baidu Waimai, offering to deliver food from a wide variety of restaurants, many of whom don’t have their own delivery mechanisms.

Comeback Plan

Clearly, Yum has lost a lot of ground in China. Yet China remains an important market. During a Q3 2015 earnings call, CEO Greg Creed confidently said: “We’ll always believe in China and we are always going to participate in its growth.”

In an effort to regain lost ground, Yum just announced that it would split its China operations into a separate company. “Yum China, a market leader with decades of accumulated consumer loyalty and world-class operations in China, will become a franchisee of Yum Brands in Mainland China,” it announced in its press release. Yum China, now headed by former CEO of KFC Division Micky Pant (he took over only in August), will have exclusive rights to the three brands: KFC, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell (not in China at this point).

“According to public reports, the spin-off was an outcome of increasing investor pressure: the shareholders do not want its lackluster China performance to hold back its stock prices,” says CKGSB’s Jing.

But is there an upside for the China division? Post-split Yum China will act as a franchisee of Yum and pay the parent company a percentage of its annual revenue. “The plus side of the split is greater flexibility of Yum China on a wide range of issues such as new product development and sales format, etc.,” says Jing.

“It’s a sensible move,” adds Zakkour. “China requires constant attention, localization and fresh ideas.” He further adds that the split will hopefully allow the China entity to update the brand, take a fresh look at menus, improve customer service and account for the new tastes of Chinese consumers.

While it is yet to be seen how the split impacts Yum China’s strategy, the company has been trying hard to make a comeback in China ever since the decline set in. It has, for instance, revamped its menu a number of times, including more local Chinese dishes even in KFC’s menu. While typically Chinese items like congee and fried dough sticks have been on KFC’s menu for ages, in 2011 they introduced rice meals in keeping with Chinese tastes.

"Why pay more?" KFC advertising coffee just outside a Beijing subway station

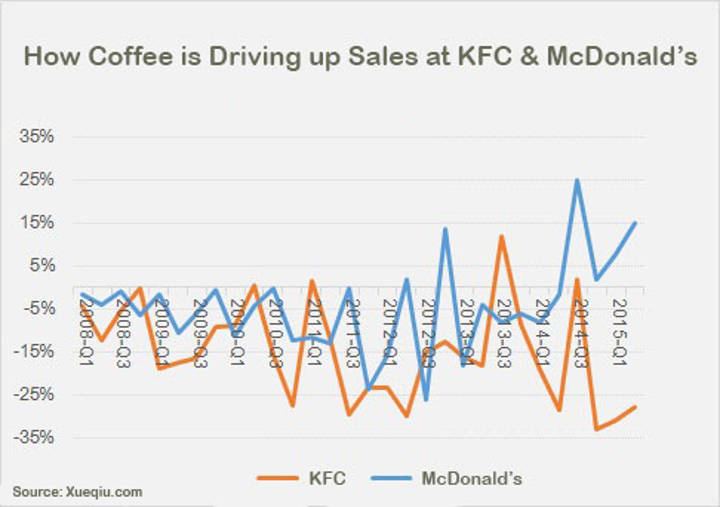

More recently KFC has ventured into Starbucks’ territory by starting to offer cappuccinos and macchiatos. Beijing’s subway stations are plastered with huge KFC coffee ads that ask the consumer: “Why pay more?”, very obviously referring to outlets like Starbucks, Costa Coffee or Pacific Coffee where the price averages between RMB 27 and RMB 33 per cup.

With the coffee move, KFC seems to have taken a leaf out of rival McDonald’s playbook which has operated McCafes in China since 2009. “By year end we expect to have premium coffee in almost 2,500 stores. Our expectation is that coffee will become a solid sales layer to further build growth upon,” Yum CEO Greg Creed said during the Q1 2015 earnings call.

In comparison to a McCafe or even Starbucks and Costa Coffee, KFC has adopted a more pedestrian pricing strategy for coffee. Analysis based on Dianping.com’s data shows that fresh coffee has already started driving sales for KFC. “Their coffee is now the cheapest in the market, about half the price of Starbucks and 10% cheaper than McDonald’s. They are likely to attract some people who perhaps are less prepared to pay for a premium coffee brand like Starbucks and Costa but want to have coffee,” says Yang from Coventry University.

“Dunkin’ Donuts is an example [of a company] that harnessed coffee to drive sales. Its sales number was affected in the past few years as people were more concerned about sugar intake. [So] Dunkin’ Donuts focused more on advertising its coffee than donuts, and their coffee wasn’t bad. So if your coffee is good enough, it is a wise decision to spend more efforts on marketing your coffee,” says Jing from CKGSB.

Coffee aside, Yum is also experimenting with new concepts.

In big cities like Beijing and Guangzhou, KFC has launched a new line of stores with what it calls the dining room concept. They sell the same food items but in a cozier dining environment with wooden furniture, soft lighting and free wifi. KFC’s regional head Huang Duoduo, described the “dining room” attempt as a “crazy idea” in an interview with a Chinese newspaper. Having gone through numerous food safety scandals, KFC’s brand image has taken a beating in China. Hypothetically the “dining room” idea stands the chance of changing consumer perceptions.

Zakkour thinks that “it’s taking them to the path [taken by] Pizza Hut, by offering a bigger experience rather than the food.” On the other hand, Gu from Mintel Group feels that by offering organic food and nutrition balanced meals, KFC will have a better chance of revival.

In yet another experiment, Yum has launched an Italian fine-dining restaurant called Atto Primo on Shanghai’s Bund. With dishes priced at RMB 300 or above, Atto Primo appears to be an experiment in an entirely new category. The Shanghai restaurant is "an innovation lab to help us learn more about the evolving tastes of Chinese consumers", Yum spokesman Jonathan Blum said to Reuters.

It is still too early to draw a conclusion on whether these strategies will turn Yum around in China. The company also had a recent leadership change: in August Yum announced that Micky Pant, formerly CEO of Yum’s KFC Division, will replace the retiring Sam Su as the CEO of Yum’s China Division. Unlike Su, Pant doesn’t really have China experience and his work is cut out for him. As per the company's press release, there seems to be enough confidence in the China business: “The business remains on pace to open about 700 new locations in 2015 and is targeting expansion to over 20,000 restaurants in China in the future.”

But getting to that goal is easier said than done. “If you have about 6,000 restaurants, that’s a big ship to turn around. You can’t do it overnight,” says Zakkour.

(The writer reached out to Yum’s press office for a comment a number of times but didn’t get a response.)

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]