[Image by pixel2013 from Pixabay]

Note: This Week in Disruptive Tech brings to you five interesting stories that highlight a new development or offer an interesting perspective. Plus, curated set of links to understand how technology is shaping the future, here in India and across the world. If you want to get it delivered to your inbox every week, subscribe here.

How do you eat an elephant?

One bite at a time. Recently, I listened to an Exponential View briefing on moonshot innovations by Sarah Hunter. She leads the Public Policy team at Google X, now, simply called X, the moonshot factory. Its goal is to build technology products that are as disruptive (and profitable) as Google Search. Google Search was essentially built in a university lab by Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. However, the next disruption will need deeper engagement with society. It has to be driven by both technology and public policy.

Hunter comes from the world of public policy. She was senior policy adviser to former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair on culture, media and sport for four years. At X, her job is to bridge the gap between technology and public policy. It is hard to bridge.

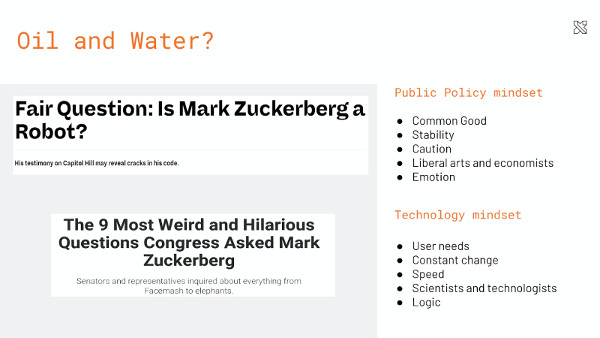

On one end of the spectrum, imagine the caricature of Mark Zuckerberg as a robot powered by artificial intelligence (AI). On the other end, imagine Barack Obama or Donald Trump, who appeal primarily to the emotions of their followers, and know how to navigate the political system.

They represent two different mindsets. Here’s a screenshot from the briefing.

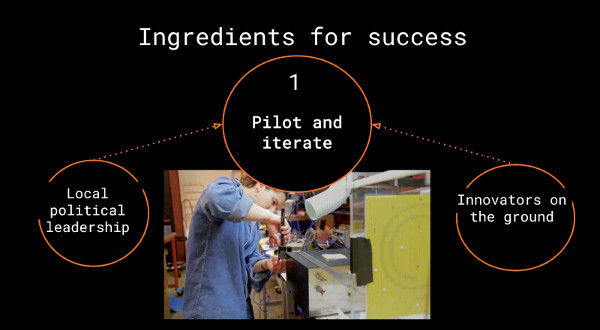

How does one bridge the gap between the two worlds? By taking one step at a time. X does it by doing small pilots that involve both technologists and local communities. “The best way to convince a politician of an idea is to convince the community first,” she says.

The best laid grand plans of rolling out technology in the society often go awry because of unintended consequences. Doing it in small scale gives an opportunity to learn and course correct.

[Screenshot from Sarah Hunter’s presentation on Zoom]

The recording of the briefing is not online, but Exponential View is one of the best places to track how technology and society intersect—and has a whole lot of conversations and curated links. Check it out.

Dig deeper

- In a blog post, Hunter explains how governments can adopt lessons from X to create a positive change. “At the heart of ‘moonshot thinking’ is a willingness to dream big, take risks and learn from failure. By setting mission-oriented goals and using techniques like small-scale pilots governments can take big bets, while minimising risk,” she writes.

- Onground reporting and big picture on X from Wired.

- An interview with Astro Teller, captain of moonshots at X, on WSJ.

How to cheat insurance companies

Mess with the metrics: Here’s an example from China.

Chinese phone cradle for boosting your phone's daily step count. Some insurance companies in China allow people who consistently reach a certain daily step count to get discounted health insurance premiums. pic.twitter.com/pJFBSYqdlb

— Matthew Brennan (@mbrennanchina) May 14, 2019

This is nothing compared to a story which should have received a lot more attention, but got drowned in the din of elections. In Hindustan Times, Snigdha Poonam and Leena Dhankhar tell the fascinating and tragic story of how a group of conmen cheated an insurance company. They picked up the bodies of people who died of cancer, enticing the family members; set them up as if they died in road accidents; got the paperwork done through conniving officials, and claimed insurance. It is far more elaborate than a device rocking a mobile phone, but the intent is pretty much the same.

It raises serious questions about how system designers in business, state and social sectors will figure out a fraud when there are multiple layers between where the action is and where the decisions are taken.

Dig deeper

- The $272 billion swindle: Why thieves love America’s health-care system | The Economist

- Wells Fargo and the Slippery Slope of Sales Incentives — by Andris A. Zoltners, PK Sinha and Sally E. Lorimer | HBR

If data is the new oil, who really owns it?

We own our data, or so they say. First, a quiz. What was “bought” with “10 boxes of shirts, 10 ells of red cloth, 30 pounds of powder, 30 pairs of socks, 2 pieces of duffel, some awls, 10 muskets, 30 kettles, 25 adzes, 10 bars of lead, 50 axes and some knives”? Answer: Staten Island, back in the days when Europeans exchanged goods for huge tracts of land in the new world. The Native Americans there got a better deal than their neighbours in Manhattan, who “sold” the island for an equivalent of $24. The words “bought” and “sold” are inside scare quotes because there are still questions on whether it was bought and sold, or whether the Native Americans got into a deal without knowing what copyright meant. Now, for how much are we selling our data to companies such as Facebook and Google?

In The Economic Times, Megha Mandavia writes that the BJP-led NDA, which is back at the helm with a fresh mandate, will focus “on the personal data protection bill, regulation of technology platforms, and support for local internet and hardware companies as part of the government’s Digital India initiative.” It could adversely impact companies such as Google and Facebook. But, who will gain? Indian citizens or big businesses such as Reliance? Is there a win:win solution?

Last week, I attended a workshop by Siddharth Shetty, a volunteer with the think tank iSPIRT foundation, on DEPA, or data empowerment and protection architecture. DEPA essentially makes sending data—such as step counts from our mobile phones—as easy as sending money on a Unified Payments Interface (UPI) app such as PhonePe. He cautioned the fintech CEOs to be prepared for regulatory uncertainty and messiness in implementation, but assured that the system will evolve, learning from the feedback.

Here’s a recording of an earlier webinar by Siddharth Shetty and Pramod Varma, the chief architect of Aadhaar. He is also a volunteer at iSPIRT and the CTO of education platform EkStep.

Dig deeper

- The data ownership delusion: Please, please, please: stop saying that the data is mine, or yours, or the dog’s — by Gianfranco Cecconi | Medium

- Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence? We are in the middle of a technological upheaval that will transform the way society is organised. We must make the right decisions now — by Dirk Helbing et al | Scientific American

- How data is eating the world, and what India needs to do | Founding Fuel

Can a group of anthropologists, mathematicians, data scientists and market specialists predict election outcomes?

They can, but don’t trust them to get it right: My colleague Charles Assisi and I were closely watching Anthro.ai which promised “ethical, machine-based systems and maps to navigate complex human landscapes.” During the recent elections, instead of looking at the entire country, they picked up a key state, Uttar Pradesh, that everyone believed will determine the re-election bid of Narendra Modi. They predicted that BSP + SP + RLD will win 54 seats in the state; BJP 21; INC 4 seats, and PSP(L) may win one.

It turned out, BJP swept Uttar Pradesh with 64 of the 80 seats.

After the results came out, they were adamant about giving a tough fight to Congress party in the department of denial. “We got it wrong. We have always maintained that if we were wrong we would be very wrong—that we would see the polar opposite of our projections. We take what little satisfaction is available from being right about how wrong we would be,” Narendra Nag, co-founder, wrote in a newsletter.

He summarised the lessons learnt in a tweet.

Our mistakes are clear — we arrived at the right insights about the people we are studying but weighed electoral impact based on an outdated political model.

— Narendra Nag (@narendranag) May 23, 2019

We now have the data we need to inform a far more accurate index of weights.https://t.co/68I56ifFNm

But the question is whether they indeed arrived at the right insights about the people they were studying in the first place, or if they got something wrong there as well. Who can resist confirmation bias?

Consider demonetisation for example

DENTED BY DEMONETIZATION - 30 constituencies have been gravely affected by demonetization, GST. pic.twitter.com/AG6VuxYUFz

— Raheel Khursheed (@Raheelk) May 22, 2019

It came with this clarification

If demonetisation's impact on the rural economy is being seen in the same way as it is among avowed Modi supporters in urban centers — a necessary step that hurt unethical businessmen — then we will be wrong.

— Raheel Khursheed (@Raheelk) May 22, 2019

The clarification is interesting because it suggests that there might be nothing like “right insights about the people we are studying”. From what we know from the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections, which gave the party a huge majority in the state assembly barely a few months after the exercise, the impact of demonetisation on people was far more complex. Arvind Subramanian explored some of it in his book Of Counsel: The Challenges of the Modi-Jaitley Economy.

German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer says simple models trump complex models because the latter often demands more assumptions. And those assumptions screw up the results.

Dig deeper

- Almost everyone got 2016 wrong. We should try to predict 2020 anyway — by Lee Drutman | Vox

- The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail—but Some Don't — by Nate Silver | Buy on Amazon

- Gigerenzer’s simple rules: Why simple rules of thumb often outperform complex models | Founding Fuel

What’s a country without its own currency?

Facebook heard it. In 2009, Facebook launched a virtual currency called Facebook Credits. The rationale was simple. Facebook users were paying different types of digital currency to buy digital goods from the applications (such as Farmville from Zynga) that ran on its platform. Instead of using them, Facebook said its citizens can use a common currency to buy products from across applications. It hired Prashant Fuloria, a top notch payments guy from Google. Its future seemed bright. The currency need not be restricted to apps on its platform, but could be used on the web in general. Its Facebook Connect, which allowed easy log in into other sites, was already popular. It was selling Facebook Credits offline, but it could even be used for offline purchases and compete with companies such as PayPal. Facebook itself could become an ecommerce company, selling goods and services based on social networking. However, it didn’t really pick up. It was charging a huge transaction free of 30%. And within three years, it shut down its Credits. Fuloria moved on, and is now COO at Fundbox.

Here’s the news. Facebook has become serious about payments, and announced that it is launching a cryptocurrency called GlobalCoin next year.

Dig deeper

- Social Cash: Could Facebook Credits ever compete with dollars and euros? — by Matthew Yglesias | Slate | 2012

- The value of friendship: Facebook is likely to become a gargantuan company. That will bring risks as well as rewards | The Economist | 2012

- Facebook plans to launch 'GlobalCoin' cryptocurrency in 2020 — by Mark Sweney | The Guardian