[Photo by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash]

Welcome to This Week in Disruptive Tech, a weekly column and newsletter that focuses on the intersection between tech and society. If you like it, please do share it with your friends and colleagues. If you have any feedback or comments, please add to the Comments section below. If you haven't subscribed already, you can subscribe here. It will hit your inbox every Wednesday.

Politicians across the world find great pleasure in showing a foreign business its place. It almost always sets off predictable reactions. Business leaders try to express their pain even while reassuring their shareholders all is well. Some of their angst is expressed through friendly journalists. The general sense is that the world is not going in the right direction.

In 1977, George Fernandes, a trade union leader, became India’s industry minister after winning the parliamentary elections sitting in jail (one of the many political prisoners who were incarcerated during the Emergency). His tenure is most remembered for driving two iconic American companies out of India—IBM and Coca-Cola. This is how Fernandes described his confrontation with IBM in an interview to the BBC later in 2006.

“IBM was very cocky. They went to the extent of telling me that they have refused to accept what the French President, General Charles de Gaulle, had told them (to dilute their equity). So I told them, ‘if you think the General succumbed to you, I am telling you that I am not succumbing to you. You get out.’ Yes, I said ‘You get out’.”

Fernandes believed he had strong reasons (and legislation, the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, was already in place). IBM was importing old machines into the country, refurbishing them and leasing them out for, what many felt, were exorbitant rates for old technology.

[IBM & Coke Ads from the 1970s]

A report in The New York Times from that time captures the mood in the US. The New York Times itself seemed to be offended by what India did, and indulged a bit in the very human habit of myth-making.

“Refusing to bow to the nationalistic demands of the Indian Government, the International Business Machines Corporation announced yesterday that it would dismantle its manufacturing and marketing operations in India.

“While that country's contribution to the computer giant's revenues is relatively trivial, the tough stand by I.B.M. may foreshadow what is to come in a string of disputes the company is having with several other developing nations.

“ ‘This particular decision will have no significant effect on I.B.M.,’ said Harry Edelson, an analyst at Drexel Burnham Lambert. ‘The danger is in the precedent. If other countries get ideas from what India and some others are doing, there could be some real problems for I.B.M. if it maintains such a hard line.’ ”

IBM eventually entered India a few years after liberalisation, and has now transformed itself into a services company, selling its hardware business to Lenovo (founded in China, interestingly, in 1984).

Cut to 2020. Donald Trump won the presidential elections four years ago, and a good part of his first term was marked by deteriorating US-China relationship. There was a simmering trade war. The biggest fight was with Huawei, and it enlisted the help of Canada and later the UK to hurt the company. His latest target is TikTok, a wildly popular video app developed in China. Recently, Trump threatened that he was going to ban the app, but later said he would be fine if the ownership shifts to an American company.

[Sarah Cooper lipsyncing Donald Trump talking about his second term on TikTok (via YouTube)]

Here’s Donald Trump on TikTok: “Right now they don't have any rights unless we give it to them. So if we're going to give them the rights, then … it has to come into this country. It's a great asset, but it's not a great asset in the United States unless they have approval in the United States.”

Trump and his team had genuine concerns about how the data is treated (they fear the data of Americans feeds straight into China’s communist party) and around censorship.

One of the newspapers from China, Global Times, exercised none of The New York Times’ restraint in commenting about the issue. GT wrote: “This is indeed the hunting and looting of TikTok by the US government in conjunction with US high-tech companies.”

It went on. “We can clearly see the ugliness demonstrated by the US government as well as the relevant high-tech giants. One of the companies hardest ‘impacted’ by TikTok has been Facebook. Its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, became the most public and aggressive promoter of TikTok's demise in the US tech industry.

“After wooing the Chinese side in order to get Facebook into the Chinese market, Zuckerberg has completely changed his face. He has declared that he has ‘ample evidence’ that the Chinese side conducted theft of US technology when the CEOs of three other US internet giants declined to confirm that. This man's willingness to set aside morality for profit shows the true face of US capitalism.”

It might seem as if the paper is overreacting. Cross-border tech acquisitions are nothing new. Lenovo acquired IBM’s PC business 15 years ago. But, this move is indeed significant as a part of a bigger trend. The vision many tech-optimists had about the internet back in the 1990s didn’t exactly play out the way many hoped. “The end of global internet” started making headlines even a few years ago. (Even earlier Pankaj Ghemawat’s World 3.0 argued that we didn’t have global internet in the first place.) But with Huawei and now TikTok (India ban, followed by US drama) we have taken more steps in that direction.

The razor’s edge of bioethics

Two years ago, Standard, a newspaper in Kenya, ran a story with the title ‘Want Cash? Volunteer for a dose of malaria parasite, says Kemri amid ethical queries.’ It was based on a paper published by a group of researchers. Kemri stands for Kenya Medical Research Institute, which was conducting a human challenge study on malaria. Human challenge studies involve deliberately infecting a healthy individual with a bacteria, virus or parasite to see how the human immune system responds.

[Clinical trials have to fight a hard perception battle. Movie Image via Amazon.com]

Scientific American reports that when the article came out, “some people took to Twitter to ask how they could sign up, while others accused the scientists of unethical behaviour.”

Scientific American went on to say: “The story infuriated Kamuya (Dorcas Kamuya, a bioethicist who evaluated participation), who felt it played into an old trope: ‘The way they framed it tended towards a storyline that has been perpetuated over the years,’ that research done in Africa is conducted by Westerners in an exploitative manner. If the article had mentioned that most of the scientists working on the project were actually African, she added, she doubts there would have been nearly as much concern: ‘They didn’t take the time to find out who the researchers were.’ ”

Kemri’s response was measured and informative. You can read it here. The whole episode serves to remind us the challenges involved not only in walking on the razor’s edge of medical ethics, but also in how it’s perceived by the public who mostly learn about it from the media.

As two vaccines get into phase three of clinical trials (administering the vaccine to a large number of people to see how effective it is compared to another group which gets only a placebo) there are more questions on whether the world should be more aggressive about human challenge studies. It means vaccinating healthy individuals, and then infecting them with the coronavirus to see if the vaccine works. (In the normal course, they don’t deliberately infect, but compare how people who got the vaccines against those who got placebo fared in the real world.)

Here’s a short reading list

- Researchers debate infecting people on purpose to test coronavirus vaccines | NY Times

- Human challenge trials with live coronavirus aren’t the answer to a Covid-19 vaccine | Stat News

- Key criteria for the ethical acceptability of COVID-19 human challenge studies | WHO

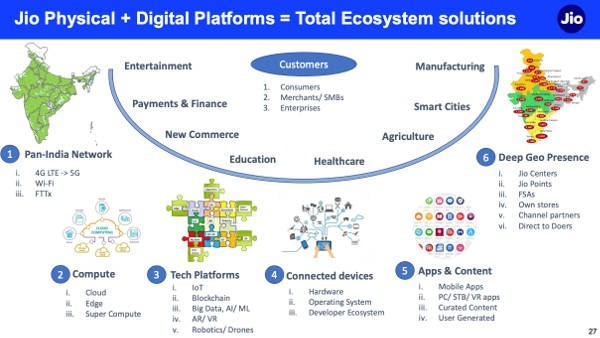

The Jio playbook was written long ago

Byrne Hobart, in his newsletter, implores his readers to understand what Dhirubhai Ambani did to build Reliance, to understand what his son Mukesh Ambani is doing to build Jio, which has hit global headlines thanks to investments from tech majors Facebook and Google.

Here’s a key paragaraph from his note:

“Reliance’s diversification shows the path businesses have to take in an over-regulated and corrupt economy. The company started out in the capital-light business of importing and exporting, then expanded into producing synthetic fibres, clothing retail, and oil refining. When they didn’t have much political pull, they couldn’t risk buying fixed assets; as they got more influence, they had a comparative advantage in taking that kind of risk. (It helped that the company’s underlying risk tolerance was, at times, flamboyantly high: Reliance once smuggled an entire factory into India, one piece at a time.) In a low-trust country, vertical integration makes sense: it’s better to control an entire supply chain than to run the risk that a competing oligarch will monopolize a key industry.”

Here’s a slide from Jio’s investor presentation that we shared a few weeks ago, that might explain how the old Reliance playbook is being executed in today’s ‘data is the new oil’ world.