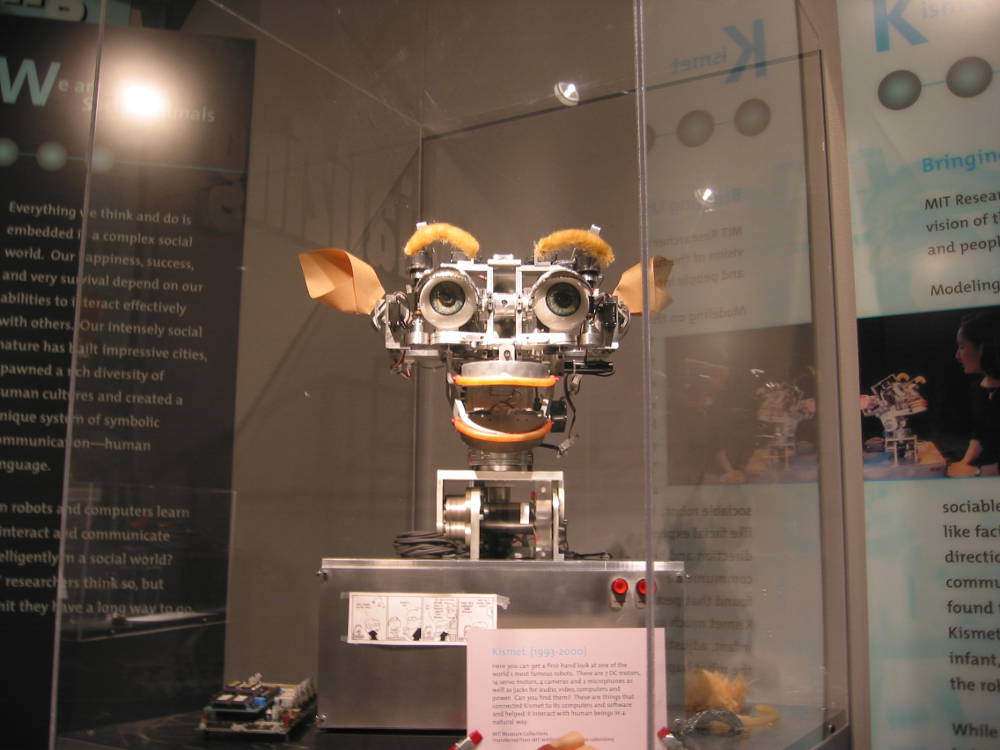

[Photgraph: Kismet the robot at the MIT museum by Polimerek under Creative Commons]

Artificial Intelligence: Will the excitement pass?

The death of Marvin Minsky last week (the artificial intelligence pioneer died of cerebral hemorrhage at Boston at the age of 88) and the tributes that followed (The New York Times, NPR, Steven Wolfram, and an AI machine) underlined an interesting fact: Artificial intelligence (AI) is not new. In fact, back in the 1980s the term evoked the same excitement and raised the same hopes that it does today. The term itself was coined by Minsky’s colleague John McCarthy in the mid-1950s. McCarthy and Minsky founded the MIT Artificial Intelligence Project in 1959. By the 1980s, AI conferences were drawing huge crowds. Many senior tech executives today—who were students then—were first drawn to computers by the promise of AI. It had captured popular imagination too. Robocop, Short Circuit and Terminator all hit the screens in the 1980s. Not just in Hollywood. One of the most popular serialised novels in Tamil during the 1980s had as its hero a robotic dog with general artificial intelligence. That huge excitement waned in the 1990s and the 2000s, before picking up in the last few years.

Will the present excitement too pass? Unlikely, for a number of reasons. Investor money, which used to flow towards business models based on the internet, now demands something more. Thus, Infosys, which primarily rode on an offshore development model (and small improvements around it), now constantly speaks about AI and automation. Companies such as Facebook and Google are investing heavily into AI. These investments are showing results. Last week, Google announced that it has built a program that could beat humans in a complex, strategic game called Go. It’s a significant milestone for AI. More importantly, AI is not just about a few researchers at a remote location writing code. It’s invading every nook and corner of serious tech companies. Mark Zuckerberg’s personal challenge for 2016, for example, is to build his own intelligent personal assistant (like Iron Man’s Jarvis).

The fourth industrial revolution

In The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living Since the Civil War, Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon argues that the third industrial revolution—the one resulting from computers, internet and digitization—did not create the same impact as the first (steam engines and factory production) and the second (electricity, mass production, etc). His arguments are US-centric, but it’s not hard to see how impactful those technological developments were.

The Indian railways—by connecting villages to cities, by enabling centralisation of production, especially certain activities like leather processing, and by merely bundling people together—“was a powerful force that cut into the rigid caste system of India more incisively than any political doctor”. Electricity changed the shape and the health of cities (there would be no skyscrapers without elevators; and there would be no sewage system with electric pumps). Telegraph and telephone made distance irrelevant—long before Frances Cairncross wrote her book on internet, The Death of Distance.

The years between 1920 and 1970 belonged to the golden age of growth. “Growth in total factor productivity (the metric that captures innovation) was much faster between 1920 and 1970 than either before 1920 or since 1970. From 1970–1994, it was only 0.57 percent a year, less than a third the 1.89 percent rate of 1920-1970. Total factor productivity growth, or TFP, was notably faster from 1994–2004 than in other post-1970 intervals, but that brief revival was an aberration: It was much shorter lived and smaller in magnitude,” Gordon writes. The title of this extract: Goodbye, Golden Age of Growth.

The fourth industrial revolution—the digital revolution—has been building on the third.

Paul Krugman, in an otherwise sympathetic, even glowing, review of Gordon’s book, points out that he could be wrong. “Maybe we’re on the cusp of truly transformative change, say from artificial intelligence or radical progress in biology (which would bring their own risks).”

Robert Gordon and innovation and growth

In fact, at the recent World Economic Forum (WEF), most of the discussions were around the huge impact these technologies will have.

Klaus Schwab, founder of the forum, setting the theme for the gala event, argued that the coming together of many technologies developed in the last few decades will transform the world as we know it. “The speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. When compared with previous industrial revolutions, the Fourth is evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace. Moreover, it is disrupting almost every industry in every country. And the breadth and depth of these changes herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management, and governance,” he writes.

As consumers we are likely to benefit from this revolution. But, much of surplus will go to those who control them, and they would need far fewer people. WEF gives hard numbers in its report, The Future of Jobs. The number of jobs that will disappear between now and 2020 because of the new technologies: 7.1 million. The biggest question over the next few years, and even decades, would be how to take care of those who lose out because of technology.

Bitcoin and blockchain

Consider these two extracts from The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story, a 1999 book by Michael Lewis. It reflects the perspective of Jim Clark, a silicon valley entrepreneur who was behind Silicon Graphics, Netscape and Healtheon, and the protagonist of the book: “Out of fear of losing yet another very public success to Benchmark, Kleiner Perkins had just paid $25 million for a 33 percent stake in a new company called Google.com. Google.com consisted of a pair of Stanford graduate students who had a piece of software that might or might not make it easier to search the Internet.” And a bit later: “With companies called Google going for $75 million, Clark did not see much point in selling air: everyone else was already doing that.”

It’s clear that Jim Clark, by no means a technology sceptic, didn’t think much about a company called Google.com. Yet now, Google (under its new name Alphabet) surpassed Apple Inc as the most valuable company in the US. The lesson from Jim Clark’s scepticism about Google is that even reasonable people can underestimate the impact of innovation, because they see so many innovations fail to make any impact at all. In 1999, there were half a dozen search engines, one claiming to be better than the other. For an outsider, every company that gets funding might look like a lemon.

In today’s context nothing highlights this perspective as well as bitcoin and blockchain. Bitcoin has a lot of sceptics. A few weeks back the most passionate discussions around bitcoin were around a superb piece by Mike Hearn, a top bitcoin developer, who started his essay with the premise that Bitcoin has failed. “Bitcoin has no future whilst it’s controlled by fewer than 10 people. And there’s no solution in sight for this problem: nobody even has any suggestions. For a community that has always worried about the block chain being taken over by an oppressive government, it is a rich irony,” he wrote.

Before the dust around that could settle, the attention turned to other applications blockchain, the distributed ledger system at the base of bitcoin. JP Morgan tied up with a New York-based startup, Digital Asset Holdings, to look at ways to use it and make transactions faster, cheaper and more secure. One area could be addressing the liquidity mismatches in loan funds.

JP Morgan isn’t the only one betting big on blockchain. Bank of America has filed for 15 blockchain-related patents, and is on its way to file 20 more. There might be quite a few bitcoin sceptics; but there are far fewer cryptocurrency sceptics, and almost everyone is excited about blockchain. And all the money and resources flowing into these promise to make a range of industries better and more efficient.

Michael Lewis on tech bubbles

Five good pieces

“The better the technology at your company, and the greater the learning opportunity, the better your chances of bringing technical employees on board, and of keeping them.”

To Hire Great Coders, Offer Learning, Not Just Money | HBR | More

“Most business activity is slowing down, not accelerating. In benchmarking the speed of key processes across the corporate sector, we find again and again that decision-making at even the most basic level has slowed materially over the past five to 10 years.”

The Hard Evidence: Business Is Slowing Down | Fortune | More

“Standards like the LAMP Stack, GitHub and Stack Overflow did such a good job of popularizing open source that they practically made it obsolete. Just like ‘mobile phones’ are simply becoming ‘phones’, ‘open source software’ is simply becoming ‘software’.”

We’re in a Brave, New Post Open Source World | Medium | More

“What happens next with Deep Mind’s Go program? In the short term, I won’t be at all surprised to see it beat the real world champion, soon enough?—?maybe in March, as they are hoping, or maybe a few years hence. But the long term consequences are less certain. The real question is whether the technology developed there can be taken out of the game world and into the real world. IBM has struggled to make compelling products out of DeepBlue (the chess champion) and Watson (the Jeopardy champion). Part of the reason for that is that the real world is fundamentally different from the game world.”

Go, Marvin Minsky, and the Chasm that AI Hasn’t Yet Crossed | Backchannel | More

“Can private enterprise really do fusion cheaper and quicker than the multibillion-dollar, government-led efforts? Hard to imagine, but investors backing the efforts are risk takers.

Tri Alpha has brought in hundreds of millions of dollars in investment, from backers that include Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen. General Fusion has attracted $94 million in funding, with Amazon founder Jeff Bezos among the investors. Last July, an investment group with connections to Canadian billionaire Jeff Skoll put money into a $10 million funding round for Helion Energy. Fellow billionaire Peter Thiel, a cofounder of PayPal, is also a Helion investor.”

Nuclear Fusion Gets Boost From Private-sector Startups | ScienceNews | More