(Photo by K HOWARD on Unsplash)

Note: Welcome to This Week in Disruptive Tech, a weekly column and newsletter that focuses on the intersection between tech and society. If you like it, please do share it with your friends and colleagues. If you have any feedback or comments, please add to the Comments section below. If you haven't subscribed already, you can subscribe here. It will hit your inbox every Wednesday sharp at 7 AM.

At one point, it looked as if Singapore had won the battle against the coronavirus. Its strategy seemed to work. It had an efficient government, its people mostly trusted it, it used technology well—its contact tracing app was widely praised. And then, suddenly, the virus came back, and started spreading in the areas that had a huge concentration of migrant labour. They stayed in dormitories.

While there are some countries that seem to have eliminated the virus—New Zealand and Finland—Singapore’s case showed that it will be a constant battle. The latest weapon Singapore has launched is a wearable device that it plans to distribute first to the elderly. Using bluetooth, the device records and remembers the other devices that were in proximity. If someone is infected, the information the device collects will help in tracing and alerting the contacts to isolate and get tested.

The world's fight against coronavirus is often framed in terms of lockdowns—whether a country imposed a lockdown or not, how early was it, how intense was it, and long was it, how gradual should the unlock be, and if things go bad, should one be imposed again, and so on. There’s no scope for consensus. In fact, the biggest ideological debates in the recent past have been around lockdowns. It shouldn’t surprise us because the world came to know, in a real sense, about the seriousness of the disease through lockdowns by China, first in Wuhan and then the rest of the country.

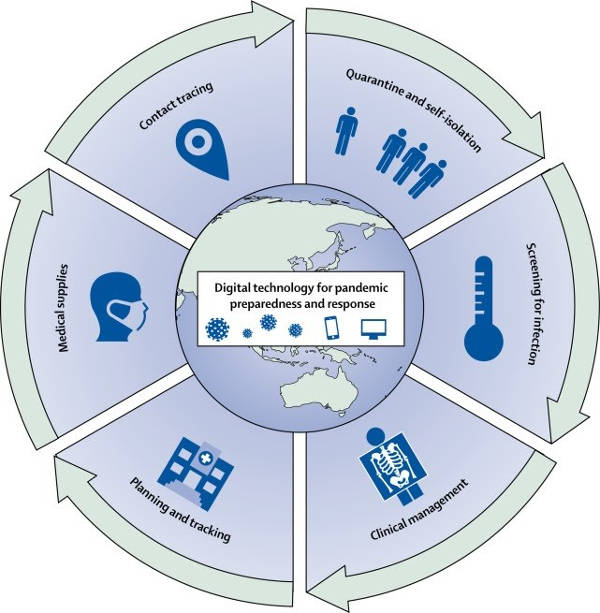

The idea of lockdown is so dramatic that it overshadows a whole range of other things that China, Taiwan, South Korea and others did in addition. Screening, masks, contact tracing, etc. The real question should be whether this package is effective, and not if a lockdown is effective.

(Image source: Lancet)

However, it looks as if lockdown is seen by those on either side of the ideological debate as something that would magically flatten the curve, and even eliminate the disease. Balaji Srinivasan, investor and entrepreneur, calls it 'cargo cult lockdown'. The term cargo cult goes back to a story narrated by physicist Richard Feynman to make an important point about science. He said:

"In the South Seas there is a cargo cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they've arranged to imitate things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he's the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They're doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn't work. No airplanes land. So I call these things cargo cult science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they're missing something essential, because the planes don't land."

It's also a good metaphor to understand why things don't work out the way we expect it to. We use some ingredients in a recipe, but not all.

It's a common mistake in the world of technology. "Want to solve education? Give students access to computers.” “Want to solve healthcare? Here's a telemedicine app.” “Want to fix the government? Make it digital.” To take the opposite stand—asserting that computers, apps or digital solutions will not help solve the problem—is no lesser mistake.

The big lesson that coronavirus teaches us is that we need a package of solutions—technology, business, ethical, cultural and even history—to solve a problem. Cargo cult devices will not work, however dramatic or sophisticated they might be.

The last man standing—gets your bucks

(Photo by Kai Pilger on Unsplash)

When Zomato bought Uber Eats in India, Haresh Chawla wrote a series of posts on Twitter on the deal and the nature of the food delivery business, and followed up with a Twitter chat with the Founding Fuel community.

He said, at the core, the food delivery business was a high-fixed cost, high-variable cost and undifferentiated business. Customers don’t care who delivers the product—they care about the particular dish they order from a particular restaurant.

He predicted that, "an extreme consolidation/shakeout of the food delivery business is inevitable, in India and across the world."

It's barely six months, and Uber, in the US, said it was buying Postmates for $2.65 billion. It would make Uber Eats the second-largest restaurant delivery service in the country by market share.

The fundamentals don't change, whether it's India or US. As a New York Times piece puts it:

“Big picture, right now, in the real world of 2020 America, food delivery isn’t working out for just about everyone involved—including restaurants, delivery couriers and certainly not the app delivery companies. They are almost all losing money. Even now, yes, when many of us are ordering more takeout and delivery.

“For the food delivery companies, the fastest way to fix this rotten system is to stop spending money in pointless ways and to squeeze more dollars from customers like you and me, the restaurants, the delivery couriers and anyone else involved in this chain of operation.

“The way to less stinkage—for the delivery companies—is having fewer but bigger companies that have the muscle to charge more for what they do.”

A facial recognition quiz

(Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash)

How often does facial recognition software misidentify people?

- 26%

- 52%

- 74%

- 96%

The answer, according to Detroit’s police chief, is here.

Read more