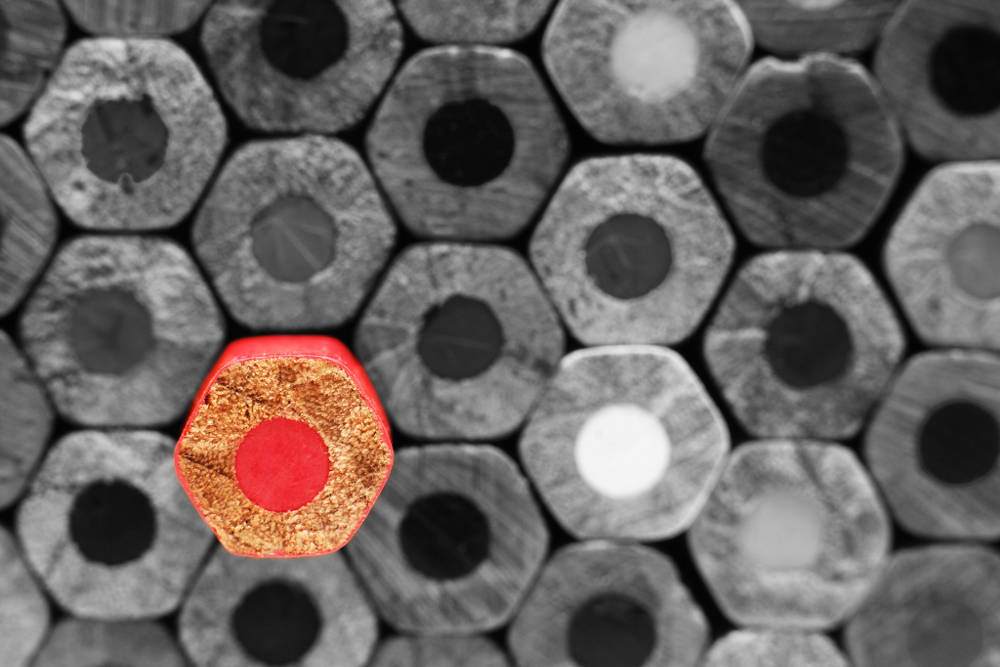

[Photograph by Olga Filonenko under Creative Commons]

By Bennett Voyles

Glory is fleeting, Napoleon once said, but obscurity is forever.

Certainly the evolution of the global market economy suggests the prisoner of St. Helena was right. In recent years, globalisation has lifted billions of people out of poverty and created vast wealth, but at the same time spawned hyper-competitive markets that make a secure niche ever more difficult to find. Everyone from cabbies to multinational businesses find it’s harder and harder to maintain an edge in the market competition.

Many forces are driving this shift, but three of the most important are deregulation, digitalisation and declining customer loyalty.

Deregulation and freer trade generally have encouraged growth of larger and more consolidated companies, but this consolidation tends to create much sharper market competition for smaller, local firms. As the US deregulated its banking industry, for instance, the share of assets controlled by banks with $110 billion-plus in assets (in 2010 dollars) grew from 17% of all American bank assets in 1995 to 59% in 2015, even as the amount controlled by local institutions worth less than $1 billion fell from 27% to 11%, according to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a US think tank. But life tends to be nasty, brutish and short for the victors as well: roughly one-third of the names on the Fortune 500 list are said to turn over every decade.

Digitalisation is also transforming many industries. On the consumer side, for example, new online entrants keep upending entire industries. Recently valued at $62.5 billion, Uber, for example, has transformed local oligopolies of metered cabs into a fight between small, local and often price-regulated fleets and a strong global brand that employs low-cost freelancers and owns no vehicles. By following a similar model, Airbnb has grown almost overnight into one of the world’s most valuable lodging brands, now valued at over $24 billion.

Finally, the fight for consumer loyalty is fiercer than ever. In the West, tough economic times, corporate scandals, and the fibre-optic grapevine of social media have all compromised the strength of brand loyalty. Only a quarter of global consumers feel very loyal to their providers these days, and nearly two-thirds (64%) said they had switched providers in at least one industry in the past year, according to a 2014 Accenture study.

Meanwhile, in the world’s younger economies, particularly China, companies face a different challenge: as markets consolidate, consumers are selecting a few favourites. “Chinese consumers are definitely increasingly brand loyal in some categories,” says Shaun Rein, managing director of the China Market Research Group in Shanghai.

Unlike Westerners who grew up loyal to particular brands, Chinese consumers did not grow up with particular brands or have parents who could teach them what was good, according to Rein. But through trial and error, they have now begun to settle on products they like. For example, he says, many Chinese customers have become attached to AMOREPACIFIC or La Mer in cosmetics, ECCO in men’s shoes, BMW or Porsche in autos, Apple in phones, Tencent in internet and Yili or Bright Food in dairy.

“Loyalty is happening because consumers are getting sophisticated—they know what they want now and go for the brands that have the right mix of quality and brand position that fit their lifestyle wants,” Rein explains.

In another arena, employee loyalty, companies also struggle to maintain an edge. Globally, Aon Hewitt, the human resources consultancy, estimates that only 25% of all employees now fall into its “highly engaged” category, while another 40% are only “moderately engaged.”

In China, the story is also somewhat different. Around 70% are at least somewhat engaged, 5% higher than the global average, according to the Aon Hewitt report. Worldwide, engagement is up 3% this year—a 12% jump over 2015. Internally, this is good news for well-liked employers, but it raises the stakes for the rest: companies that aren’t keeping up can expect to have a harder time competing. Alienated employees are expensive, according to Aon Hewitt analysts. Companies with low levels of engagement suffer from higher absenteeism, lower productivity, lower customer satisfaction and lower shareholder returns.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the table, individuals also have to struggle more than ever to stand out. As a rule, job candidates who are older or less skilled tend to have a harder time. In particular, people who find themselves on the wrong side of a barrier to entry, such as membership in a professional organisation, possession of an advanced degree, a union card or privileged demographic status (such as being white in the West or male practically everywhere), tend to have a tougher time winning much pricing power in the job market.

Lack of clout tends to translate inevitably into lack of market power. For example, in the US, middle-wage workers’ real wages have risen only 6% since 1980, even as very high wages (incomes at the 95th percentile) have risen 41%, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a US labour think tank. Similar stories have played out in the developing world too, as a rising tide of opportunity tends to lift some boats faster than others.

This lack of pricing power is always a bad sign. As the legendary investor Warren Buffett, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, said, in the context of business valuations, “If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10%, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

So how do you escape from what is sometimes called the commodity box?

When it comes to companies, there are three primary ways to add more value: innovation, better quality, or better branding, according to Hermann Simon, chairman of Simon-Kucher & Partners, a strategy and marketing consultancy, and author of Hidden Champions.

Of these, he says, innovation and branding are the most important—and, for Asian companies, he says, also the most difficult: the former because innovation doesn’t fit with a tradition of imitating by example; and the latter because behind every strong brand, there tends to be a crazy person. “Steve Jobs is the best example. And deviating in this way from the mainstream is not sanctioned in [Asian] culture. Jack Ma of Alibaba fits the pattern, but he is a rare exception in China. In Japan, Masayoshi Son of SoftBank is such a person, he is actually of Korean origin and not respected by ‘true’ Japanese,” Simon claims.

One of those crazy people, Andy Grove, the late CEO of Intel, argued that success in business requires making a decision. Companies die less often because they make the wrong decision than that they make no decision at all. “I believe Mark Twain hit the nail on the head when he said, ‘Put all of your eggs in one basket and WATCH THAT BASKET.’”

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]