[From Pixabay]

Good morning,

In The Hard Thing About Hard Things, Ben Horowitz draws a distinction between two types of CEOs whose style is defined by the challenge they are facing. He explains the difference this way: “Peacetime in business means those times when a company has a large advantage over the competition in its core market, and its market is growing… In wartime, a company is fending off an imminent existential threat.”

Horowitz goes on to highlight a number of differences between the two. Here are seven of them

- Peacetime CEO knows that proper protocol leads to winning. Wartime CEO violates protocol in order to win.

- Peacetime CEO focuses on the big picture and empowers her people to make detailed decisions. Wartime CEO cares about a speck of dust on a gnat’s ass if it interferes with the prime directive.

- Peacetime CEO builds scalable, high-volume recruiting machines. Wartime CEO does that, but also builds HR organizations that can execute layoffs.

- Peacetime CEO spends time defining the culture. Wartime CEO lets the war define the culture.

- Peacetime CEO always has a contingency plan. Wartime CEO knows that sometimes you gotta roll a hard six.

- Peacetime CEO knows what to do with a big advantage. Wartime CEO is paranoid.

- Peacetime CEO strives not to use profanity. Wartime CEO sometimes uses profanity purposefully.

The list underlines a larger point. There is no cookie cutter approach to leadership and management, because everything is contextual.

Have a great day.

How Forbes destroyed journalism

Even as the internet started to explode with content and started its assault on media business models, it dawned on everyone that new models would have to be thought up. Advertising revenues would not be enough. And one of the models that Forbes.com deployed was to create a contributor network. Albeit, surreptitiously. Just how bad the rot has gotten is captured in a report by Joshua Benton of Nieman Lab.

“Forbes’ staff of journalists could produce great work, sure. But there were only so many of them, and they cost a lot of money. Why not open the doors to Forbes.com to a swarm of outside ‘contributors’—barely vetted, unedited, expected to produce at quantity, and only occasionally paid? (Some contributors received a monthly flat fee—a few hundred bucks—if they wrote a minimum number of pieces per month, with money above that possible for exceeding traffic targets. Others received nothing but the glory.)

“As of 2019, almost 3,000 people were ‘contributors’—or as they told people at parties, ‘I’m a columnist for Forbes.’

“Let’s think about incentives for a moment. Only a very small number of these contributors can make a living at it—so it’s a side gig for most. The two things that determine your pay are how many articles you write and how many clicks you can harvest—a model that encourages a lot of low-grade clickbait, hot takes, and deceptive headlines. And many of these contributors are writing about the subject of their main job—that’s where their expertise is, after all—which raises all sorts of conflict-of-interest questions. And their work was published completely unedited—unless a piece went viral, in which case a web producer might ‘check it more carefully.’

“All of that meant that Forbes suddenly became the easiest way for a marketer to get their message onto a brand-name site.

“And since this strategy did build up a ton of new traffic for Forbes—publishing an extra 8,000 pieces a month will do that!—lots of other publications followed suit in various ways.”

Dig deeper

The Hedonic Treadmill

Why are people unhappy? This is a theme that interests us deeply and is a question Arthur C Brooks investigates in a beautifully written essay in The Atlantic.

“Scholars argue over whether our happiness has an immutable set point, or if it might move around a little over the course of our life due to general circumstances. But no one has ever found that immediate bliss from a major victory or achievement will endure. As for money, more of it helps up to a point—it can buy things and services that relieve the problems of poverty, which are sources of unhappiness. But forever chasing money as a source of enduring satisfaction simply does not work. ‘The nature of [adaptation] condemns men to live on a hedonic treadmill,’ the psychologists Philip Brickman and Donald T. Campbell wrote in 1971, ‘to seek new levels of stimulation merely to maintain old levels of subjective pleasure, to never achieve any kind of permanent happiness or satisfaction.’...

“So you try and you try, but you make no lasting progress toward your goal. You find yourself running simply to avoid being thrown off the back of the treadmill. The wealthy keep accumulating far beyond anything they could possibly spend, and sometimes more than they want to bequeath to their children. They hope that at some point they will feel happy, their lives complete, and are terrified of what will happen if they stop running. As the great 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer said, ‘Wealth is like sea-water; the more we drink, the thirstier we become; and the same is true of fame.’”

Dig deeper

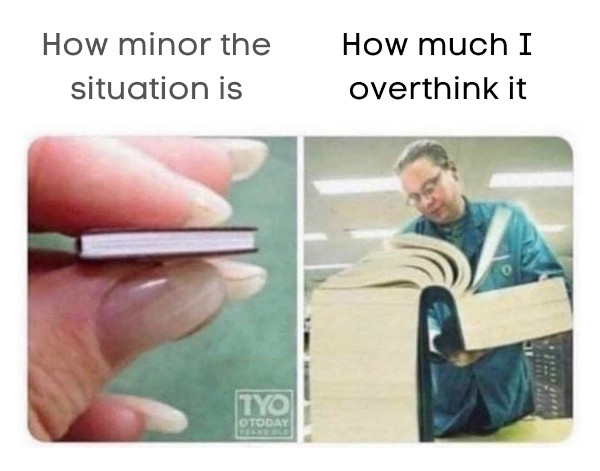

The proportionality principle

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)