[From Pixabay]

Good morning,

Just how did the Indian IT services business get to be as big as it is today? There is much work that happened behind the scenes and Harish Mehta describes all of it in his book The Maverick Effect. Some of us have known him for many years now as part of the founding members of Nasscom, the industry body that represents the industry. In this extract, he describes how the body and its president Som Mittal then handled the fallout of the Satyam scam.

“The media was brandishing it as the ‘Satyam scam’. I felt it was inaccurate. It was clear that one man was the perpetrator. Hundreds of thousands of other people associated with Satyam were innocent. It should have been called the ‘Raju scam’, if at all. In such cases, typically, the first thing the authorities do is put a lock on the gate of the company. Som advised them against it and instead, worked with them towards saving the company—an unprecedented initiative in the history of India’s government-industry relations. It was easier said than done. How was anyone going to save a listed company that had been cooking the books? The government was obviously ambivalent. So, Som decided to go to ground zero to be closer to the situation and work in concert with government officers, so that they could make informed, collective decisions. Within a few hours, Som was on a flight to Hyderabad.

“He reached Hyderabad around midnight and straightaway met Satyam’s senior management. He saw that everyone was in absolute shock, just like us. The whole team was in disarray, clueless about what had hit them. Som collected all the information he could till four in the morning.

“Hours later, when Som returned to Satyam headquarters, he found the entrance was overrun with camera crews, and TV production trucks were all over the place. If the media recognized him, the news flash would read: ‘Nasscom president spotted at Satyam HQ’. This was clearly not desirable. So, Som sneaked in from the back of the building. He had to scale a wall!”

Mehta goes on to describe how the government intervened, why Mittal declined to join the board of Satyam, and finally Kiran Karnik was appointed as chairperson. Not just that, he describes other actions behind the scenes. “When a giant like Satyam falls, it is natural for competitors to swiftly poach key employees and clients. To ensure Satyam’s survival, it was vital that there be no poaching.” To assure Satyam’s clients, Mehta writes, “Som reached out to Satyam’s clients, assuring them that the company would not be dissolved and their projects would be delivered as committed.”

Everyone responded. Satyam was eventually taken over by Tech Mahindra. How Mittal handled the Satyam fallout is a lesson in leadership as well.

Have a good day!

SoftBank’s underbelly

Now that valuations are getting hammered, people are beginning to examine who and what drove the frenzy. This is why we read a profile of Masayoshi Son, the billionaire investor and entrepreneur, the driving force behind SoftBank, with much interest.

“Back in 2019, I warned that SoftBank’s $100 billion Vision Fund was a doomed venture for everyone but investors: it might achieve returns, but at the cost of propping up inefficient monopolies whose survival seemed unlikely. Familiar names like Uber, DoorDash, and WeWork, but also Indian hotelier Oyo or now-defunct construction company Katerra, all were given large hoards of capital to use as weapons against competitors in their respective markets. But for many of its portfolio companies to earn their first profit, or to sustain those they were beginning to enjoy, they’d need more than cash to burn—they’d need to restructure society to realize profits that were previously illegal because of basic laws protecting workers and consumers.

“Things turned out even worse than I anticipated. SoftBank and the Vision Fund have become a disaster for everyone including investors, marking the decline of a calamitous era… In May, SoftBank revealed it had lost $13.2 billion overall last fiscal year, with the Vision Funds suffering a nearly $27 billion loss.”

So what does this mean for SoftBank?

“The looming threat of antitrust crusaders, a slow deflation of some tech valuation bubbles, and the failure of SoftBank’s portfolio companies to achieve sustainable profits have all contributed to an IPO market too weak for SoftBank to realize gains on investments. And all this has also led to a growing amount of debt on SoftBank's books as SoftBank takes out loans against its assets and issues bonds to pay investors in the Vision Fund. Investors have started to doubt whether SoftBank is actually good for that debt: on Tuesday, Moody’s downgraded SoftBank’s credit rating from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’—the second downgrade in as many years.”

Does this mean Son is now a pushover and SoftBank will be history soon? We think it’s a little too early to make such assertions. But we’d urge you to read this narrative and share your thoughts with us.

Dig deeper

The worrisome legacy of Jack Welch

The New York Times’s business reporter David Gelles is out with a new book on Jack Welch. The book's title reveals what Gelles thinks about Welch: “The Man Who Broke Capitalism.” In an interview with the substack publication The Ink, Gelles says he is not against capitalism in general, but what it has become.

He says, “I think free enterprise has its merits and has lifted tens, maybe hundreds, of millions of people out of poverty into better living conditions.

“So I don't want to lose sight of that broader narrative. The way I would personally refine that question is to ask, are those types of dramatic negative externalities necessary? Are they inevitable? I would say the answer is no, because we know that companies have choices. These are choices that people make about how they run their companies. Individuals, mostly men, made a series of choices that led us to those places.”

One of the decisions that GE’s Jack Welch took was financialisation of the company.

Gelles says, “Financialisation is a term that encompasses the economy’s broad shift away from an economy of things and toward an economy of services, specifically financial services. Welch saw this coming in the 1980s and positioned GE to capitalise on it. Wall Street was the fastest growing industry in the country, as new technology-enabled banks, hedge funds, private equity firms, and trading outfits created more complex financial instruments to trade more volume at ever greater speeds.

“What financialisation enabled is almost more influential than the practice itself because it manipulated earnings. By squeezing profits out of the company with a black box financial entity like GE Capital, Jack Welch was able to be at the vanguard of this enormous revolution of shoveling the profits earned by a corporation back to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividends. Remember, that was the money that used to be going to its employees, suppliers, and the government in taxes.

“As all those parties got a smaller and smaller piece of the economic pie generated by these big companies, want to know who got an ever larger piece of pie? It was the institutional shareholders, namely the Wall Street firms and the executives themselves, through greater and greater stock-based compensation."

Dig deeper

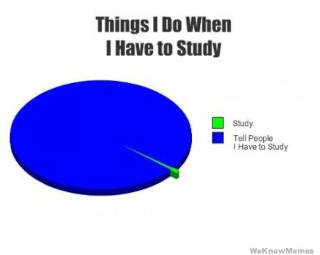

Procrastination explained

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel