Good morning,

Three months into 2021, and there is every indication that more cataclysmic changes are underway.

We selected the top 5 Founding Fuel stories of the first quarter that give an inkling of how the ground is shifting. Here’s the list. Each story is supported with a short personal take on “the story behind the story” from the person who wrote it or anchored the piece/conversation. They talk about what went into developing the idea, interesting anecdotes, and the new ideas and possible follow ups the piece or conversation has triggered in them.

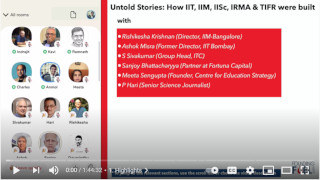

Untold stories of how India built its higher ed institutions

Back in the 1950s right up to the 1980s India built world class institutions—TIFR, IIT Kanpur, IISc, IRMA, and IIM-Ahmedabad. These are also stories of visionary leadership and the principles they stood for.

Watch the video (104 mins) or read the accompanying summary (8 mins)

The story behind the story

By Indrajit Gupta and Charles Assisi

About a week ago, Pratap Bhanu Mehta and Arvind Subramanium’s momentous decision to resign from Ashoka University over the lack of academic autonomy came as a bolt from the blue. Other than sketchy information gleaned from their resignation details, no one quite knew the insider details of what had exactly transpired—and we still don't—but that didn't stop every TV channel and every columnist worth their salt from sharing an opinion on the issue. As a niche platform, our challenge was quite simply this: how could we stay away from the noise—and yet offer our community an insightful and engaging way to understand the deeper issues at play?

That's how the idea of dipping into our own history of higher education in India emerged—and even though we are saying so ourselves, it turned out to be a masterstroke. All of it was thanks to the gems in our Founding Fuel community—luminaries who intimately know the history of how IIT-Kanpur, IIM-A, TIFR, IISc and IRMA were built. And could surface little-known stories of how a set of extraordinary leaders—Homi Bhabha, Satish Dhawan, Ravi Matthai, PK Kelkar and Verghese Kurian—shaped these institutions.

We chose to host it on Clubhouse, the buzziest social media platform right now. To be honest, we had our share of apprehensions on whether it would work. Based on the feedback that we've received so far, it seemed to have struck a chord. And the option of recording the live session for our wider community worked well too. Now, you'll need to tell us what you think. One thing is for sure: we will do more such meaningful conversations on Clubhouse this year. Do join our Founding Fuel club there.

And we have few invites to Clubhouse left. If you’re on an iPhone, reply to this email with your name and number where we can send you a link.

Why only three companies will dominate global markets

Jagdish Sheth, Rajendra Sisodia and Can Uslay talk about their latest book The Global Rule of Three: Competing with a Conscious Strategy. It builds on Sheth and Sisodia’s original work, The Rule of Three, published nearly two decades ago. The original idea said there will be two kinds of competitors—generalists and specialists—who may co-exist in the short term, but there are always three generalists in the long run. They take over the market from specialists and vice versa. Others fall in the ditch.

In the two decades that have passed, some things have changed: It’s still a rule of three, but technology and globalisation have brought a major transformation in the world.

Watch the video (84 mins) or read the accompanying summary (7 mins)

The story behind the story

By Indrajit Gupta

It was simple and straightforward. You don't say no when one of the best known global management gurus invites you to anchor a panel discussion on the occasion of his new book launch. That was how I was pitchforked into anchoring a conversation—and Founding Fuel stepped in as a knowledge partner—at the virtual launch of The Global Rule of Three, a new tour de force by Professors Jagdish Sheth, Can Uslay and Raj Sisodia.

Now, imagine my surprise at the start of my session, when I discovered just who had dropped in for the chat: marketing guru Philip Kotler and the world's best known CEO coach Ram Charan, both close friends of 'Jag' Sheth! And a sizeable bunch of frontline academicians and CEOs from India and the US. Fortunately, I didn't drop the ball that evening. Or else, I wouldn't have been able to live that down.

I walked away from the session with one clear insight: if we aspired to substantially upgrade the quality of management research in India, the spotlight had to be on how to improve both relevance and rigour. It was a treat to tune in to not just the story of how the three authors had collaborated on the research, but also to better understand how the forces of globalisation had changed the rules of competition, strategy and marketing.

Systems thinking, state capacity and grassroots development

That there’s much that doesn’t work in India’s state machinery is a truism. But how do you juxtapose that with things that do work? Why do they work? What is the state—and what does it mean to increase state capacity? Who are the changemakers and how do you democratise solution-finding?

These were some thoughts that emerged in the discussion, which was driven largely by M Rajshekhar’s recent book, Despite the State: Why India Lets Its People Down and How They Cope. The conversation was led by Arun Maira (former chairman, BCG India and former member, Planning Commission) and included Mekhala Krishnamurthy (associate professor, Ashoka University), Harish Hande (Magsaysay award winner and co-founder of Selco India), and M Rajshekhar.

Watch the video (112 min) or read the accompanying summary (11 min)

The story behind the story

By Arun Maira

That minimum government will create a better state of being for citizens has become the mantra since Thatcher and Reagan declared their governments as the enemies of their own people fifty years ago. Adam Smith said that it was the ‘market’ that, with some ‘invisible hand’, creates goodness in citizens’ lives. Yet, our instinct is always to blame ‘the government’ when things don’t go right—like blaming God when Nature does not provide.

The ‘state’ is more than the government of the day. It is a combination of forces that create the social conditions in which we live and work, just as Nature, with the interplay of myriad energies, creates the environmental conditions for sustaining our lives.

So, when Rajshekhar set out on his odyssey to see how the state functioned on the ground from the perspective of India’s citizens, especially the poorest, I suggested he put the atropine drops of ‘systems thinking’ in his eyes. Systems thinking, like atropine, forces one to ‘un-focus’, to see the full picture. It enables one to see what is happening around the events that concern us.

Mekhala, with her trained eye of an anthropologist, is a great systems observer. Just as every species, even those ugly to the eye, play an essential role in maintaining the integrity of the natural environment, she has educated me about how, for example, ‘middle-men’ who we may denigrate as parasites in the economy, enable the system to function. Harish Hande taught me how he too had learned to un-focus his trained engineer’s eyes while solving complex social problems. Bringing light into poor people’s lives was not as straightforward as providing solar lanterns on scale, he found.

The publication of Rajshekhar’s book, Despite the State: Why India Lets Its People Down and How They Cope, provided a wonderful occasion to bring these three systems thinkers together to understand why we are in the state we are 75 years after our Independence when India proudly formed its own government.

Trendspotting 2021 with Nandan Nilekani & Haresh Chawla

This is a decisive moment in India’s digitisation. The digital rails were put in place over the past decade and 2020 saw a dramatic acceleration of trends that were already happening. Nandan Nilekani and Haresh Chawla discuss the many ways India could ride this train

Watch the video (47 min) or read the accompanying summary (4 min)

The story behind the story

By Haresh Chawla

My annual Trendspotting piece this year was an exercise in rejection. With the pandemic and the lockdowns, the canvas was sprawling. Everything was undergoing seismic shifts. It’s fascinating to observe the shifts taking place around us—my notes are copious and in the end, I had to cut away 80% of the material to make the column readable. So, I thought why not anchor it in a conversation with Nandan Nilekani? Nandan has a unique vantage point at the intersection of business, society, government and technology. So that’s what we did.

The session was fantastic. It ran through at breakneck speed and we covered so much ground.

If you watch the video, I wonder if you will notice the chaos that was going on at my end. It’s like Murphy was sitting next to me and randomly pointing his finger at my equipment. With just seconds to go, my laptop hung, so I quickly shifted to my smartphone—literally a minute before start!

My table had a stack of books, and my MacBook Air was delicately placed on top. On top of that I had placed a small tripod with the phone—very precariously. I was nervous that even if I touched this superstructure in front of me it will come crashing down. My notes were on the laptop, but I didn’t dare touch it.

Then imagine, a few minutes into the discussion, my phone suddenly informs me that it is down to 20% battery. I was wondering how to charge it? So while the conversation was on and the camera was on Nandan, I creeped my hand out and connected the charger cable—like I am disarming a nuclear device. Ah! It worked and I kept a straight face. With great relief I got back to focusing on the conversation.

The next ten minutes went smoothly. And then my AirPods beeped a warning that they are about to run out of power. Luckily I had kept a spare wired headphone next to me. Now the dilemma: should I remove the charging cables and risk the phone running out of battery or should I push in the wires? There was no way to do both. And then, what will happen if I shift over? Will the whole structure collapse? I had to pull out the wire.

Luckily, I had the charger, I had the wired earphones. I hadn’t thought the laptop would choose to hang at the last minute or that a fully charged cell phone would have been a great backup.

Net, net, when things go wrong, keep a straight face and keep going. And of course, always have a backup plan.

The feedback on the Trendspotting conversation and the accompanying essay was fantastic and I am so glad that thousands of professionals responded. It has inspired an idea that I should explore other themes in the changing landscape around us with great minds like Nandan. I hope to turn this into a series of conversations soon.

Finding Abdul

Abdul was mentally ill, lost, and his life condemned to the boondocks. But a programme conceived at Tata Trusts has given him a chance to live again. This narrative is how they did it and the thinking behind a different approach to providing care to those with severe mental disorders.

Read it here (7 mins)

The story behind the story

By Dr Anand Bang

What we left unsaid in the narrative about how those of us at Tata Trusts crafted a programme to reform the regional mental hospital at Nagpur is that we had first met with failure. But we learnt much along the way and are at work on much else.

The first time we attempted reform was at the regional mental health hospital at Yerwada in Maharashtra. This place has 2,000 beds. We had done our homework and our plan was in place. But when we got there, it started to sink in that we had taken on more than we could handle. There were too many issues on the ground that included managing stakeholders across the ecosystem. We weren’t equipped.

By way of example, to implement the change we wanted in how the wards are structured, we would need to co-opt the Public Works Department (PWD). But they had other priorities. There was no way all that we had brainstormed would come to life. Reality was different.

So, we scaled our plan down, made a note of the lessons learnt, and zeroed in on the hospital at Nagpur that has 600 beds—less than one third our original plan. We needed allies as well. So, we informally communicated with Devendra Fadnavis, then chief minister of Maharashtra, to inform him of what is on our mind for mental health institutions. It did help that I was also acting as the honorary advisor to him!

Fadnavis proactively wrote to Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Trusts and requested the Trusts to collaborate with the state government. Usually, it is the NGO or the philanthropists who knock at the doors of the government to collaborate. This was a first. Soon after that, an MoU was signed on March 31, 2016, in the Maharashtra Assembly, and the chief minister made a statement on the floor of the House while Tata was watching from the visitor’s gallery. It was a remarkable sight, especially when the entire House, cutting across party lines, applauded the partnership. It elevated the programme and sent a clear signal that with backers such as this, it cannot be ignored.

On the government’s part, the principal secretary (health), director (health services) and additional director (mental health services) regularly pitched in with advice. Our team at Tata Trusts had learnt by then that we must consistently communicate all progress we make at regular intervals to every stakeholder in the government and our supporters in the philanthropic sector. To do that, we opened direct communication channels and ensured on rigorous formal reviews internally at periodic intervals.

This is not to suggest that all philanthropic projects are in need of government support. Each project is unique. My only submission here is that one learning which emerged is that it is important to map out all the stakeholders in the project, engage with them, and get them to collaborate.

This collaboration has gotten us to a point where we have something to show by way of tangible reforms at the Nagpur mental hospital and it is being spoken about as a success. But it started off on the back of failure.

This failure, though, has gotten us to a point where we can think about making this a model that can be replicated and scaled across other parts of the state and country. It has offered us pointers on how to craft policy when it comes to mental health issues. This includes what kind of systems can we implement that can attract volunteers to work at mental hospitals and destigmatizes cliches most Indians have in their minds around such hospitals.