[Techies have to work a lot more with fuzzies before the benefits reach people at large. Fintechs believed that more data and better algorithms can reduce costs and take finance to new markets. They are now realising that it’s hard to capture the complexities of human behaviour with algorithms. Image from Unsplash]

Indian fintech used to be marked by optimism

Even a few years ago, there was tremendous optimism about the fintech industry in India. Many believed that fintech companies were on an unstoppable rise, growing their user base, introducing innovative products, capturing market share, and enabling financial inclusion in India.

Venture capitalists poured billions of dollars into Indian fintech, egged on by rosy reports from analysts and consultants. Companies such as Paytm, PhonePe, PolicyBazaar and Razorpay were constantly making headlines as they secured huge investments and became unicorns, companies with over a billion in valuation. Some of them went public.

The industry's focus was on scaling up. Fintech entrepreneurs and the VCs who funded them believed that the hard problem of showing that technology worked for finance had been solved. Now, it was only a matter of expanding the market. “Our job is to find and fund entrepreneurs who can hack growth,” a VC declared at that time.

The optimism has now been replaced by concerns about fintech’s future

However, in the past couple of years there has been a serious rethink. The exuberance that defined the mood of the fintech industry melted away. Some of the well-funded companies that were betting on the segment are pivoting, or at least hedging their bets, either because they see the landscape without the rose-tinted glasses of yesteryears or because those glasses have been snatched away from them by the harsh reality.

For example, even back in 2018, Instamojo, which raised funds from Kalaari Capital, Mastercard, and AnyPay for its payments gateway business, realised that the road ahead was going to be tough and pivoted to a SaaS model for e-commerce, helping direct-to-customer services. Since then it has become profitable.

Similarly, Niyo, a company founded by two ex-bankers from Standard Chartered and Kotak Mahindra and funded by Accel, has now expanded to launch a travel tech platform. Its founders explained that its core products were no different from what other companies offer: “Niyo could do something to gain an edge but how much can someone differentiate a normal savings account?” one of the co-founders said.

Lending has always been core to banking and finance and held a huge promise for fintech. But digital lending has been one of the hardest hit, by regulations and the reality of the market. For example, ZestMoney, a leading buy-now-pay-later company with investments from Goldman Sachs, Omidyar Network, and Zip, found itself in a corner as losses mounted. It tried to sell itself to BharatPe (which itself has fallen into tough times), Pinelabs (which is doing better), and finally to PhonePe (a decacorn, owned by Walmart thanks to its acquisition of Flipkart). It looked like the deal would go through, but PhonePe pulled back saying the company failed their due diligence. ZestMoney laid off over 100 people and is now trying to turn itself into a SaaS player.

Companies that went for IPO are trading at a discount. Paytm, which started trading on stock exchanges in November 2021, is selling at less than half its IPO price. PolicyBazaar is down by 33%. Others such as Mobikwik which was planning for an IPO are postponing it.

The industry is currently at a crossroads

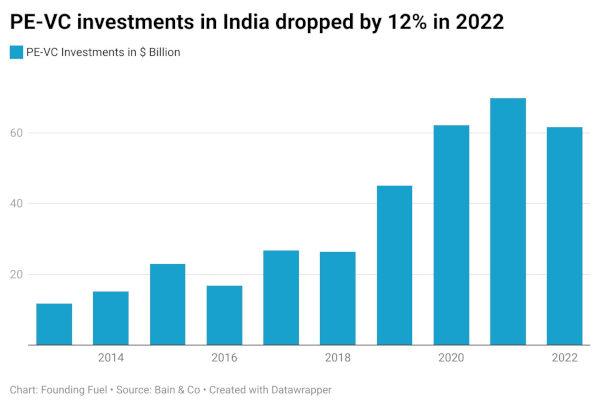

These examples reflect the broader struggles of fintech players. Among all the unicorn fintech companies, only one, RazorPay, is making a profit. VC investments which kept the fintech companies afloat, are saving their dry powder. The number of deals and the size of investments in the fintech sector fell by over 50% in 2022. VC investments dropped by over 70% in the first half of 2023. While companies were fighting for talent during the height of the pandemic, there have since been hiring freezes and even layoffs. At least 650 people were fired last year from fintechs according to a Longhouse Consulting analysis for The Economic Times.

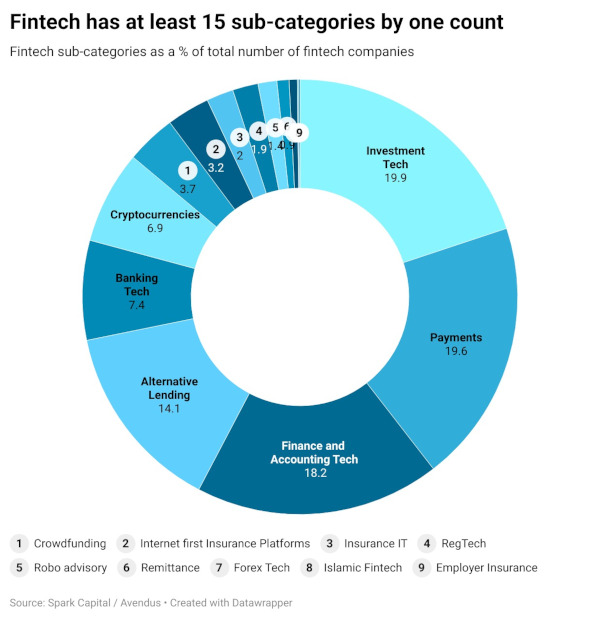

Now, exuberance has been replaced by introspection. As a result, the future of fintech will not be a scaled-up version of what is there today. It will be different. There is already a range of fintechs — enterprise, consumer-facing, payments, lending, insurance, wealth management, advisory, etc. — today, each with its own characteristics.

Some will change much more than others, but the future will be different for all. "It's part of the evolution of Indian fintech," says Ram Ramdas, co-founder of Wonderlend Hub, a digital credit gateway platform. "We are right in the middle of the first and second phase of that evolution."

The shape of its future depends on three factors: a) its partnership with established players; b) its willingness and ability to look beyond technology; and c) its relationship with regulators.

How the industry shapes up in the coming years depends on three factors.

First, how well the incumbents and challengers are able to work with each other, rather than against each other. About ten years ago, the dominant narrative was that the nimble new players will eat the incumbents such as banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) for lunch. The playing field seemed to be in favour of the challengers. It has changed since then, thanks to a number of reasons, including the path India took to developing the basic digital infrastructure. Now, many have started talking about collaborations and partnerships, rather than competition.

Second, how well technologists can make room for “buggy humans in a messy world” (as the title of the newsletter of a value investor puts it), even as they use technology. For many technologists, and by extension, for Fintech startups, it is a matter of faith that more data and better algorithms can replace human effort. This is the way to bring down costs and take finance to new markets, they believe. This was one of the reasons for optimism about fintechs. Now, some of that is turning into scepticism. Financial data is incomplete. The use of alternative data often throws up spurious correlations. There is a growing realisation that technology can’t yet replace people on the ground, and it’s hard to capture the complexities of human behaviour with algorithms. Techies have to work a lot more with fuzzies before the benefits reach people at large.

Third, how well the ecosystem finds the balance between regulation and innovation. VCs and entrepreneurs want to focus on innovation. RBI is focused on customer safety and systemic stability. In the past, many fintechs have tried to push the system towards innovation, even if it comes at the cost of customer safety and systemic stability, and the RBI has asserted its authority every time. As this continues, the big question is how much fintechs can innovate, while ensuring it's aligned with the two big goals of the regulator.

How the industry deals with these three issues is important

While fintech has come a long way in the last ten years, the road ahead is still long. How fintech impacts the world of finance, business and society at large will depend on what’s happening on the ground right now.

We’ll cover the ground reality in Part 2 of this special report, as fintechs realise they need to collaborate, not compete, with incumbents.

Read all 4 parts here.