[Bangalore Literature Festival. Photo from https://bangaloreliteraturefestival.org]

India is gearing up for its end-of-year festivities. The next few months will be marked by the vibrant energy of festivals like Durga Puja and Dussehra, followed by the nationwide glow of Diwali. This festive spirit flows into a bustling season for book, music and art lovers, with major events like the Mumbai LitLive in November; the Chennai Music Festival, Bangalore Literature Festival, and the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa in December; and the Kolkata, Hyderabad and Jaipur literary festivals in January.

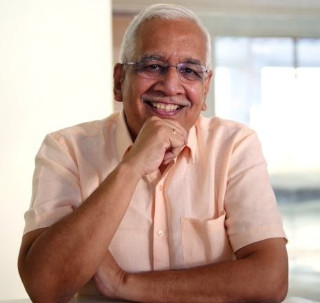

Last year, we had invited V Ravichandar to share his experience building Bangalore Literature Festival, a cultural event drawing top writers and tens of thousands of visitors—all without corporate sponsorship. Ravichandar’s recent work spans the 13-year journey of the Bangalore Lit Fest where he is co-organiser, the city-wide BLR Hubba where he is the chief facilitator, and key experiments like the Bangalore International Centre (BIC). He explained how its unique community-based funding model and volunteer-driven operations gave it freedom and made it sustainable over the years.

“The beauty of this approach is that nobody can claim to control the festival. Sure, people get outraged and ask, ‘Why did you call this person?’ or ‘Why did you call that person?’ That happens every year. But we're not dependent on any single entity. No one person owns the festival. In that sense, we de-risk it from the potential of a large sponsor suddenly pulling out,” he said.

Ravichandar’s piece generated huge interest and thoughtful conversations. You can read the full story here.

At Founding Fuel, we followed it up with an AMA session with Ravichandar and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, whose formidable portfolio includes a decade of restoring Indian film heritage through the Film Heritage Foundation and taking on the director’s mantle at Mumbai’s MAMI film festival, and driving initiatives like the Raj Kapoor Centenary celebrations.

They spoke about the evolving challenges and creative solutions at the intersection of arts, culture, community, and funding—demonstrating how Indian festivals can remain inclusive, independent, and resilient by harnessing diverse models, engaging genuinely with audiences, and putting shared purpose above individual interests.

You can read the key takeaways from the session, or watch the hour-long session down below.

With the festival season about to start, we went back to Ravichandar for a follow-up on the earlier conversation. Then our focus was on sustainability and independence. Now, we also asked him about a third pillar—inclusiveness. In this piece, he pulls back the curtain on what it takes to make festivals work.

The Soul of a City: Cultural Festivals and Public Spaces

By V. Ravichandar

I am closely involved in four projects: Bangalore Literature Festival, BLR Hubba, the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) and Sabha.

This broadly falls under the heading of revitalising public spaces in the city. At one level, this involves both creating new public spaces and revitalising existing ones. To me, public spaces are places where communities gather—whether for literature events, arts and culture, or simple conversation. They are essentially a city's dimension, bringing together a community of people interested in a particular area, much like the bazaar cultures of old.

The making of vibrant public spaces

They come in two forms. The first are physical spaces where communities can gather, which we can either create or revitalize. An example of a newly created space would be the Bangalore International Centre (BIC), or Sabha. These are the "hardware" of the system, and they require the right "software"—or the essential programming—to become vibrant public spaces.

The BIC and Sabha are physical spaces designed for community gatherings, and it is through engaging programs that the goal of fostering informed conversations, arts, crafts, and culture is met. These venues are open all year round. Although they may only accommodate between 100 to 300 people at a time, you can introduce a wide range of programs to attract a diverse audience.

[Versatile spaces: Sabha, inner courtyard. Image Courtesy: Sabha]

In contrast, the Bangalore Literature Festival and the BLR Hubba are annual events. They tend to be much larger in scale. For example, the Literature Festival attracts about 25,000 people over a weekend, while the Hubba draws approximately 200,000 people over a span of ten days.

These events are highly focused: the Literature Festival centers on literature, while the Hubba features 10-12 different genres, including drama, dance, theatre, music, heritage walks, and Kannada-language programming. This wide variety of programming is packed into a short, ten-day burst across about a dozen locations. The Literature Festival, while held at a single location, offers variety through different literary genres, such as fiction, non-fiction, and science fiction, along with dedicated content for children, all within a two-day period.

If you do the math, the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) draws about 300 people per day on average, which translates to roughly 9,000–10,000 visitors per month, or around 100,000 people in a year. The BLR Hubba, on the other hand, attracts 200,000 people in just ten days.

This difference in scale can be compared to a cricket match, where a single match might draw 40,000 people, and a series of five matches brings in 200,000. In other words, the scale and reach in terms of the number of people who are exposed to the events are vastly different.

A city’s brand identity

These initiatives help shape a city's brand identity beyond its typical labels like "startup and tech capital" or "pothole capital." They raise the question: is this a cool place for arts and culture? This cultural appeal can even attract talent, as spouses might be more willing to settle in a city like Bangalore because it’s a "happening place." It's not just a city known for its pubs; it also offers events like the Literature Festival and venues like Ranga Shankara, Jagriti, and the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), which provide families and children with a broader sense of purpose and life.

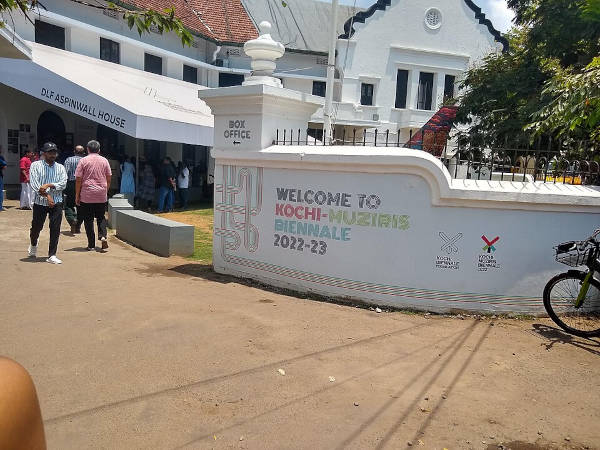

These larger events create a sense of community quickly and become significant brand products for the city. For example, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale may happen every two years, but it's a defining aspect of Kochi's identity. Similarly, Goa has the Serendipity Arts Festival, and Mumbai has the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival. All of these serve the same purpose: they foster a sense of civic pride and offer opportunities for engagement with arts and culture. They create a wonderful communal experience where strangers can share a common emotion evoked by the performance on stage.

[Kochi Biennale. Image: N. Vivekananthamoorthy / Wikimedia]

Smaller cities, local traditions, and osmosis

When I look at smaller cities like Coimbatore, I see a need for these kinds of public spaces. While the scale can be different, creating physical spaces that foster conversation, arts, and culture is essential. These cities also need to build on their local traditions and customs to create a signature event that puts them on the map and gives residents a sense of civic pride.

For example, the Karaga festival in Bangalore (which honours the goddess Draupadi) is one such event. More of the educated middle class needs to understand and appreciate the Karaga. If it were the Rio Carnival, everyone would say, "Wow, I want to go!" We need to reach a point where we can cross-pollinate and cross-assimilate these experiences. The English-speaking, non-Karaga-attending middle class should be encouraged to witness a Karaga festival, and in turn, those steeped in that tradition might be motivated to find out what's happening at the BLR Hubba.

Overcoming fear of others

As a society becomes richer in terms of GDP, initiatives like these become even more important.

They serve another crucial purpose: in an increasingly polarised world, where there is a fear of "the other," these events bring people from different backgrounds and nationalities together. They create a melting pot for the community, fostering a sense of unity.

What it takes to organise these events

You need a group of people who are passionate about the idea of creating and revitalising public spaces. For me, it's a mission, and it requires about 10-15 dedicated individuals.

In a country with widespread issues like poverty, health, and education, some might question the importance of arts and culture. However, a growing body of research now highlights the significant impact of art and culture on overall well-being and mental health.

An appealing, inviting city

The second essential component is finance. The Bangalore Literature Festival costs us about Rs 3 crore per year, while the BLR Hubba costs Rs 12 crore. You have to be able to make a strong case for why it is worthwhile for high-net-worth individuals or organisations to support these initiatives. The case I make is this: we often talk about ancient India, where maharajas and maharanis were great patrons of the arts and culture. Today, our billionaires, startup founders, families with inherited wealth, and large corporations are the modern-day maharajas and maharanis. This approach truly moves the needle. We have successfully run the Literature Festival for 13 years by fundraising from individuals, and we are now in our third year of running the Hubba with funding from corporations.

For corporations, supporting these initiatives goes beyond simple brand building; it's also a question of what it means to be a good corporate citizen in the city where they operate. The question is, does their responsibility end with the mandatory 2% CSR contribution, or does it go beyond that?

Corporates understand the logic that to retain their best talent, a city needs to be appealing in every respect. This includes addressing issues like traffic and garbage, but it also means having good parks, gardens, cultural events, and public spaces. The social infrastructure needs to function just as well as the physical infrastructure.

Committed volunteers

You need a group of people who can curate, ideate, and organise—the core force behind either a physical space or a specific event.

The curation aspect is key. For example, for the Hubba, we put together a team of 22 people to work on various aspects. You must have the ability to mobilise a team that can handle different parts of the festival and bring it all together. Similarly, the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) has a program committee. These models are applicable at different scales in cities like Coimbatore, Tirupur, or Kolhapur as well. The limitation isn't the city's size; it's the mindset of saying, "We are small."

[Nartisu Hubba, a dance festival. Image: BLR Hubba Instagram page]

Communal assets

In addition to the four examples I'm directly involved with, I have also been part of initiatives focused on public parks, which are vital community assets. In Bangalore, a movement to revive public spaces is underway, and 108 people have submitted suggestions on how to improve their local areas—everything from footpaths and roads to lakes. The goal is to identify and transform an asset in a neighbourhood into a quasi-public space.

I believe the future lies more in these privately-enabled, public-purpose efforts. While nothing prevents the government from becoming more actively involved, inviting citizens to think differently about how public spaces can be utilised is a powerful approach.

The risk of becoming elitist

Assimilation and cross-pollination are challenging. Many of these initiatives, let's face it, are quasi-elitist. For example, while 15% of the programming at the Bangalore Literature Festival is in Kannada, the audience demographics are clearly from a particular mid-to-higher-end segment. We all face the risk of becoming elitist.

However, we have managed to make progress at the Bangalore International Centre (BIC). A decade ago, it was primarily attended by an older demographic. But through a conscious effort to create programming for millennials and Gen Z, more than half of the current audience is under 40 years old.

For example, a new initiative at the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) has designated the library as a children-only space every Sunday for six-to-thirteen-year-olds. The idea is to provide a dedicated space for parents with young children, who are often overwhelmed and lack places to spend quality time with their families.

On Sundays, families can come to the BIC for reading, library access, and other activities. This initiative often introduces new visitors to the centre, who might say, "I didn't know the BIC existed. What do you do here?" This discovery then leads them to attend other events.

Can I get drivers or vegetable vendors to come?

However, that still doesn't solve the problem of how to reach a wider spectrum of society. I've tried to address this at the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) by encouraging drivers to come inside and watch the performances while their bosses are in the audience. But they often tell me, "Sir, my boss is sitting right there; how can I sit there?" There are significant obstacles, and there's no easy fix.

Still, certain initiatives, like the Karaga festival, are more accessible. I intend to use venues like the BIC or Sabha ahead of major city festivals to expose our demographics to traditions they might not be aware of. Hopefully, this will encourage 10-20% of them to attend the actual event, whether it's the Kadalekai Parishe (an annual groundnut festival) or something similar.

The responsibility to be more inclusive falls on the elite. This isn't just about raising money; it's also about ensuring that marginalised voices are heard through thoughtful programming.

Our approach is to create a space for the marginalised by hosting programs on topics like LGBTQ issues and other progressive subjects. However, even then, it's still primarily our existing audience that comes to listen to these stories.

The day a vegetable vendor walks into the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) to attend a program, I'll know we've truly succeeded. Technically, they are welcome, but they still feel intimidated. There's no easy fix, but the effort to make these spaces truly inclusive must be made.

Nothing stops us from partnering with organisations like Hasiru Dala (a social impact group that works with waste pickers) to offer them a dedicated arts and culture evening. It's possible to create such opportunities to attract a broader audience. I constantly think about this. I'm aware that the initiatives I'm promoting can come across as quasi-elitist, but I believe it's important to start somewhere.

Non-intimidating venues

[Freedom Park, Bengaluru Image: Gpkp/Wikimedia]

For example, we're moving the Bangalore Literature Festival to Freedom Park this year. We decided against using five-star hotels because we wanted to be in a true public space. This location also has parking for 650 cars, which we felt was an important consideration. Hosting the festival at a venue like the Lalit Ashok, while a nice place, can be intimidating to some people. Moving to a public park makes it much more accessible and welcoming to a broader audience.

My main point is that you have to integrate with the community. For example, at Sabha, we knocked on the doors of about 400 houses in the surrounding neighbourhood to create a database of households. We then offered free art classes every Saturday for the children, since the area's profile is more middle to lower-middle class.

Now, we have about 50 children from the neighbourhood who attend these classes every Saturday. This shows a dedicated effort to integrate with the local community, which is crucial.

Tailoring an option to showcase and boost livelihood

The next thing I'm planning to implement within the next year—it's still just an idea for now—is a two-day event for the hundreds of tailors in my community. The goal is to provide them with a platform to showcase their craft and earn a livelihood, since they are my neighbours.

Additionally, when the IPL finals were on, we invited our entire neighbourhood to watch the match at Sabha. That event drew a completely mixed crowd because it wasn't the typical elitist programming we usually host.

(As told to NS Ramnath)

AMA with V. Ravichandar and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur

(Play time: 62 min. Read Time: 5 minute)

This AMA with two influential figures in India’s business-of-arts space was held in December 2024. Together, their experiences cover the spectrum of film, music, and literary arts—making this session a deep dive into what powers cultural movements in India.

Key Takeaways

1. Shrinking public spaces, need for inclusive forums

Cities are losing safe, open spaces for arts and dialogue. Festivals can reclaim this ground by being accessible, inclusive, and community-led.

“We’re getting increasingly polarized and conversation-safe spaces are shrinking. Can we create relatively safe spaces that are inclusive and accessible?” - Ravichandar

2. Film heritage is misunderstood and undervalued

Film preservation goes beyond Bollywood; it includes documentaries, scientific films, and regional cinema. The country produces over 2,000 films in 50 languages, almost six major film Industries, and very little understanding of what is film heritage.

“BNHS (Bombay Natural History Society) called me, saying there are some films of Dr Salim Ali, the ornithologist. We want some Bollywood guys to look at this. I said what has Bollywood got to do with it? Your board has every big industrialist. It was sad that nobody got together to digitize those films. It was digitized by the British Museum and we worked on those films.” - Dungarpur

3. Independence and sustainability in funding

Keeping festivals free from dominance by one funder is key. Broad-based donations and small contributions help preserve independence and integrity.

In its first year, the Bangalore Lit Fest tried the traditional model of corporate funding. It fell through with two weeks to go. They pivoted to a crowdsource model. In 13 years they’ve raised close to Rs 20 crore from the community.

“No one person calls the shots. We make it a point not to take more than 5%—most people’s donation is below 3%… this model has legs.” - Ravichandar

4. Corporate sponsorship vs. authentic programming

Corporates prefer glamour and star power; genuine cultural work struggles for attention. Independent positioning matters. A large sponsor will want to impose their branding.

A community-run, volunteer-driven “brandless” festival can build more trust and resilience than corporate-sponsored ones.

“We are brandless, community-run—basically run by volunteers... when you raise money from individuals, you broad-base the collection, and credibility will increase. If you have one sponsor who more or less takes 50% and gives you crores of rupees, you have to dance to their tune.” - Ravichandar

“There was no question of any sponsorship at the beginning. That changed when Tata Trust gave us a grant. They recognized that film is an important cultural entity. Others are more attracted if there is a big celebrity coming in. Nothing has changed in that mindset….

“At MAMI, Jio was the main supporter much before I took over. But they took the branding of Jio… I think the institution should remain as an institution. The moment you say independent cinema is going to be the focus, corporate supporters start getting uncomfortable.” - Dungarpur

5. Challenges in getting support for film archives and restoration

A large part of the support came from some of the greatest filmmakers in the world. George Lucas for restoring the Kannada film Ghatashraaddha by Girish Kasaravalli; Martin Scorsese for restoring the Malayalam film Thampu by Aravindan.

“When Martin Scorsese said to one of the producers, can I just restore it, he couldn't understand. He says what will I get for it? Martin said I don't want anything, I just want to give you the money to restore it. So he said, ‘If you want to restore it, I want Rs 1 crore’.” - Dungarpur

6. Open festivals and government as an enabler, not controller

The government's ideal role is as an enabler, providing permissions and logistical support, not direction or funding, allowing for greater inclusivity. Heavy government involvement can politicize festivals and narrow their scope.

“The government… shouldn’t be the 800-pound gorilla trying to do arts and culture….

“With the BLR Hubba, we showed what is possible in the city center. All the gigs were free to attend. If you do sufficient Kannada programming, all sections of society come. On average, 1,000 to 1,500 people visited per day…

“At the Bangalore Lit Fest, 20% of our programming is Bhasha—predominantly Kannada, but also Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Hindi. The same festival when it is done by the government, it's an out and out Kannada festival which excludes many people who don't understand the language.” - Ravichandar

7. Finding the right patrons

“I could not find a single person who wanted to donate for Gandhi's actual Dandi march footage. Because it was not cool. They’d rather give for a Sholay.” - Dungarpur

“I believe strongly that free makes things accessible. Five years ago when we opened BIC, Shubha Mudgal, Aneesh Pradhan and their team came for two days of Gandhi Jayanti songs. When she heard we are free to the public she said Aneesh and I won't charge you, but pay my fellow artists because for them it's a living. Artists reciprocate.” - Ravichandar

8. Attracting a wider audience

Mix of children’s sessions, headline speakers, and diverse genres ensures broader participation and audience discovery. Festivals need to create space for children and families. Programming is a continuous challenge. Being authentic comes through in the selections that you make.

“One year we had Rahul Dravid. You can say what does Rahul Dravid have to do with literature. But 1,200 people were there an hour early for his session. Afterwards, they said, I’m already here, let me walk around and consume what is happening….

“Children are central to our programming. That's how you bring the millennial parents out.” - Ravichandar

“During Covid, one of the most interesting concepts was ‘Bachchan Back to the Beginning’ festival (across several cities), which is now a retrospective of big stars…. It brings classic cinema back into theatres—Dilip Kumar's films, Dev Anand or Raj Kapoor….

“In MAMI, we started the opening film with Payal Kapadia’s film [All We Imagine as Light], and not a big Hollywood film or a big film of Europe. We wanted to celebrate an Indian filmmaker.” - Dungarpur

9. Curation integrity

Festivals need to hold firm against pressure from publishers, sponsors, or ideology. Leaders must step aside if credibility is at risk.

“You could be the founder of the institution but if you put the institution at risk, you walk.” - Ravichandar

10. Engaging younger audiences

Curating fusion music, contemporary formats, and inclusive performances draws Gen Z and millennials.

“I’ve done two Gen Z videos… and strangers are stopping me saying, you’re the Gen Z uncle…

“We had TM Krishna with the Jogappas (a community of transgender folk musicians) at the Hubba and 600 people turned up despite the rain. They obviously may not have been purists because purists don't like him…. you try to bring everybody. We open the festival with TM Krishna, we close it with Sanjay Subrahmanyan, the Carnatic vocalist. You try to balance.” - Ravichandar

“We've never had a problem with the crowd; we’ve always had over a thousand people coming for even an old film like Dilip Kumar’s Devdas. What is important is the curation.” - Dungarpur

“Back in 2005 - 2010, at BIC, the attendees were all old-timers, retired people. One has consciously worked to take the audience to the 30-plus class… We do 500 events per year, free, across multiple genres—something for everyone… in a month out of 40 events, if you circle three and say I want to go for this, our job is done.” - Ravichandar

11. Innovation in audience engagement

Encouraging interaction among attendees and giving them voice adds richness.

“We need to leave four or five badges—‘Talk to me about…’—so strangers know you are open to conversation….

“Or a kind of Hyde Park after the session… you give a Hyde Park box outside and let random guys stand up and say I have a better point of view on the subject. Even if four people listen to him you are at least recognizing that the audience has as much intelligence…

“Another Innovation—we tried it, it works—is leave an empty chair on the stage and the person who sends the most insightful question on the subject ahead of the event gets to sit on the table for the last half an hour of the discussion“ - Ravichandar

12. Volunteers as cultural custodians

Festivals thrive on committed volunteers motivated by passion, not certificates.

“We typically get about 150 people showing interest. We say come at this time for a briefing. We only work with those who land up….

“The problem with volunteering is they think they’re doing you a favour. We want volunteers who are there for the right reasons.” – Ravichandar

13. BLR Hubba as a scalable model

Can we put up a thing on scale, just like Serendipity in Goa, or the Kochi Biennale, the Carnatic music season in Chennai, or the Edinburgh Fringe—something that celebrates the city, for people to experience.

A city-wide, multi-genre, largely free festival demonstrates how to brand Bangalore for the right reasons and seed future properties.

It puns around with the English word ‘hub’. In Kannada it's ‘habba’—a festival. BLR Hubba—Bangalore as a hub not just for startups and new technology companies, but also for arts and culture.

“We had three premises: something for everyone—so 500 events, something near you—42 locations, and access free.” - Ravichandar

Dig Deeper

- The existential dilemmas facing cultural festivals: Can a festival survive and thrive without corporate sponsorship? Yes—and here’s how Bangalore literature festival found freedom through community funding

- Shivendra Dungarpur begins a new Manthan: For a decade, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur took on the formidable challenge of almost single-handedly resurrecting India’s film heritage. The Film Heritage Foundation, his not-for-profit venture, now has an ambitious, new plan for the next decade