[Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay]

The State versus Big Tech slugfest is the most compelling global narrative of our times. China rolled out a series of regulations. In Europe, the stringent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018 regulating the big players of the tech industry was a watershed moment. In the US now, the Biden administration is witnessing bipartisan support to regulate Big Tech.

It’s a global game, but it is playing out differently in different geographies. The histories and motivations are different, and the lessons are different too.

In this four-part essay, we explore the State Vs Big Tech conflict in China (Read Part 1 on China here), the EU, and the US, and draw lessons from there.

According to The Economist, the EU accounts for less than 4% of the market capitalization of the world’s 70 largest tech platforms. The region is dominated by Big Tech players of American (73% share) and Chinese origin (18% share). However, with more than 500 million users, this region contributes to one-fourth of Google’s and Facebook’s revenues.

The American tech companies are extremely wary of what is called the ‘Brussels effect’. Given the significant size of the European market and the costs involved to offer customized services outside the European region, Big Tech has essentially designed its digital services as per GDPR, Europe's stringent privacy laws introduced in 2018. Today, GDPR is considered the gold standard in extensive tech regulation. More than 120 countries are taking inspiration from GDPR in framing their own rules for the technology sector. Even the American regulators acknowledge that the EU has the first mover's advantage in introducing antitrust action to rein Big Tech players.

GDPR, however, has led to high compliance costs. It has led to tech companies spending more than $100 million globally, because firms had to invest in legal services and revisit their digital business plans in a short period of just more than two years, and were forced to hire chief data officers. In 2019 alone, Google was fined $57 million for various violations in the EU market. Earlier in 2017, Facebook was slapped with fines worth Euro 110 million for misinforming the EU regarding its plans to integrate WhatsApp with its flagship social network.

Economic Motivations

Policymakers in the EU region have voiced numerous concerns about the overwhelming impact Big Tech has had. The issues range from Big Tech not paying taxes, to more fundamental objections about their unethical business practices. For instance, some regulators allege that tech companies are highly whimsical about revealing and hiding data and are never forthright in ensuring transparency. Such practices have led to more serious accusations that Big Tech compromises users’ privacy and engages in antitrust rules.

The EU is also very discrete regarding Big Tech because frequent technological disruptions have a severe repercussion on some of the major industries like telecom, automobile, and media. It is worth mentioning that countries like France and Germany have constantly egged on the EU officials in Brussels to introduce stringent measures in regulating Big Tech players from the US. These countries are motivated by the desire to protect businesses that are intimately connected to the moves of the major tech industry players. French President Emanuel Macron was once quoted stating that “if the US has GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple), China has BATX (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and Xiaomi), EU has GDPR.”

Regulators in the EU have very closely scrutinized takeovers of startups, believing that Big Tech incumbents are so eager to maintain their pole position that they acquire any new startup that has the potential to become their rival. According to observers, American Big Tech players like Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft have taken over at least one company per week from 2015 to 20.

Political Motivations

The EU’s keenness to regulate Big Tech stems from an ecosystem that is strikingly different from the hands-off approach adopted by the American system. Unlike the American system, which has been overwhelmingly driven by the twin motives of promoting innovation and profit maximization, the regulatory environment in the European region has always been more conservative and regulators have always been wary of giving free rein to Big Tech. The policymakers have always been under pressure to keep the politicians and public in good humour, prompting regulation of foreign companies and ensuring customization of their offerings in the region. Throwing light on this aspect of Europe's regulatory framework, Charles River Associates, an economic consultancy, commented that European regulators, by and large, discourage cartels and are inclined to promote even those regional firms which don’t enjoy quick success. In short, for European regulators, competition is an end in itself.

There’s a historical context to this wariness of big business: Europe was inflicted with totalitarian ideologies like Nazism and Fascism in the past century with utter disregard of individual freedom and privacy. Given the frequent allegations that Big Tech players infringe on privacy, European regulators are keen to ensure a stringent anti-privacy regulatory regime. The enshrining of privacy in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is testimony to the sanctity associated with it.

Regulatory Measures in the EU

The EU has broadly adopted a two-pronged approach to tech regulation. The first approach has mainly focused on protecting individual privacy; the second has been to check cartelization by Big Tech firms.

There is consensus among regulators that every individual should enjoy unconditional ownership of personal data. The common argument is that questions related to determining the right to access, amend, and usage should be under individual purview. Allegedly, Big Tech players like Facebook and Google have compromised individuals’ privacy and abused it for commercial objectives. GDPR seeks to address these questions by giving customers control over their privacy and informing them about the monetization of their data. One way of achieving this objective was to allow interoperability between services, enabling customers to have more control over their privacy and check monetization of data without their knowledge.

Further, it was argued that this would lead to healthy competition among tech firms and, in turn, benefit customers by compelling firms to raise the standards of services.

To check cartelization of the tech business, for instance, the EU has blocked attempts by Google to disadvantage its rival shopping sites that appear in its search results. Similarly, Google has also been barred from discouraging rival browsers using its Android operating system.

Germany's Battle with Facebook

Germany, Europe’s largest economy, has always been very conservative in its approach to Big Tech. For instance, it has invoked the concept of market power to prevent Facebook from gobbling up new players even before they can stand on their feet. Market power, or monopoly power, allows a company to raise prices above the level that would prevail if competition existed—and without losing customer base. Regulators typically raise the issue of market power to justify antitrust action. In Facebook’s case, this is how its market power plays out: With its free offering Facebook continues to track users, without their knowledge, while they browse sites not even remotely connected to Facebook. This ability to accumulate data has provided Facebook ample market power. According to e-marketer, an aggregator of e-business and internet statistics, data generated by online users and collected by apps and browsers is the bedrock of online advertising—a business that is worth $108 billion. And Facebook has pole position in this market.

German regulators have questioned how Facebook collects data, eliminates the possibility of any competition in the future, and consolidates its position in the market—and have restricted it from collecting German users’ data. In other words, given that Big Tech players possess a massive cache of personal data and the immense possibilities of abusing it for their commercial objectives, the European region has tended to link privacy concerns with competition in the market. The defining logic is that access to personal data provides enormous market power.

The GDPR Effect

GDPR, which the EU introduced in 2018, is considered one of the most stringent privacy and security laws globally. In the world of tech regulation, GDPR's influence came to be referred to as the ‘Brussels Effect’.

People all over the world are entrusting their data with cloud services, and there have been frequent breaches. Although drafted and implemented by the EU, the law applies to all organizations dealing with the privacy of European citizens. The law mandates that compromising citizens’ privacy will be met with fines amounting to millions of euros.

In December 2020, the EU regulators initiated discussions on the two drafts of two acts to further check the growing influence of Big Tech. The two acts are the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Marketing Act (DMA). DSA clarifies the responsibilities of internet companies for taking down illegal content. This act also proposes to set Pan-European standards and define liability in unambiguous terms. In addition, the act seeks to establish specific rules to ensure transparency of advertisements and check the spread of false information.

DMA seeks to impose new restraints on gatekeeper platforms. The draft proposes a list of rules for internet platforms regarding activities that are considered illegal and liable to be subjected to antitrust actions. Besides, the act aims to force significant amendments to the existing business models of the Big Tech players operating in the EU region. If the tech companies violate the law, hefty fines amounting to 10% of their global turnover are to be imposed. If these companies fail to pay penalties, they will be forced to break up into smaller entities if fined thrice in five years. Through this act, the EU regulators seek to overcome the traditional enforcement tools which mandated lengthy and complex regulations that led to litigations. The act aims to curb the advantages of Big Tech players emanating from the network effect that leads to self-preferencing behaviour. Further, the act proposes that internet platforms operated by Big Tech players marshal data to silos and ensure access to rivals under interoperability rules.

Challenges in Enforcing Big Tech Regulation

Despite the stringent regulatory environment, enforcement has been a significant challenge. To begin with, owing to the prohibitive compliance costs of GDPR, smaller companies, especially the local ones, have found it very difficult to compete on an even keel. In other words, ironically, such measures have strengthened the dominance of Big Tech and are likely to reinforce their monopolistic tendencies.

Second, there is a lack of clarity regarding the rules governing emerging technologies in fields like AI, Blockchain, and IoT.

Third, there’s no consistency among member states in the way their regulatory authorities interpret the EU law. They enforce it by mapping certain rules to specific tech domains. This has compounded the problem of uniform implementation across the EU region.

Activists battling against Big Tech for safeguarding individual privacy have frequently voiced concerns about how users of online platforms often tacitly compromise their privacy so they can reap the benefits of online services. The Covid pandemic has increased reliance on Big Tech and its services and heightened the concerns that there’s a tacit acquiescence of Big Tech compromising on individual privacy. Small businesses, some argue, will be deprived of the ‘halo effect’ (their ability to leverage their brand) and ‘global reach’. For instance, some small business groups and their associations have expressed apprehensions regarding the stringent regulations introduced by the EU authorities. They contend that these regulations will dampen the prospects of startups who nurse the ambitions of being acquired by Big Tech players. They argue that they could indirectly impact local SMEs’ business models and consequently their growth ambitions. Unicorns say that they will find it more challenging to get VC funding and, therefore, will find it extremely difficult to scale up their business and pose any threat to Big Tech in the near future.

Despite the crackdown on Big Tech, there is still no consensus in the EU on the merits of tech regulation. In the words of Thierry Breton, EU commissioner for the internal market, “there is a feeling in Brussels that online platforms have become too big to care.” Another policymaker is quoted stating, “the internet as we know it is being destroyed… Big platforms are invasive, they pay little tax, and they destroy competition. This is not the internet we wanted.” Pro-regulators widely echo this sentiment.

On the other end of the spectrum, Ian Hathway, well-known entrepreneur, investor, and author of The Start-up Community Way, contends that “governments do have a role to play, just not the one politicians often want it to be.” People like Hathway believe that overexuberance on the part of regulatory authorities will stifle the innovation of tech companies.

Meanwhile, some studies point out that two trends are visible in the tech business in the European region. According to The Economist, the market share of tier two and tier three firms has risen from 18% to 21% in the last five years. Second, as their core products mature and Big Tech diversifies to explore new opportunities, regulation could stifle innovation in emerging areas by singling out Big Tech players unfairly. Given these challenges in legislating and enforcing Big Tech regulation, it will be fascinating to see how the State versus Big Tech debate unravels in the EU.

Editor’s Note

Part 3 of this series on State Vs Big Tech will be published on Wednesday, September 15. It covers the regulatory scenario in the US. You can read Part 1 on China here.

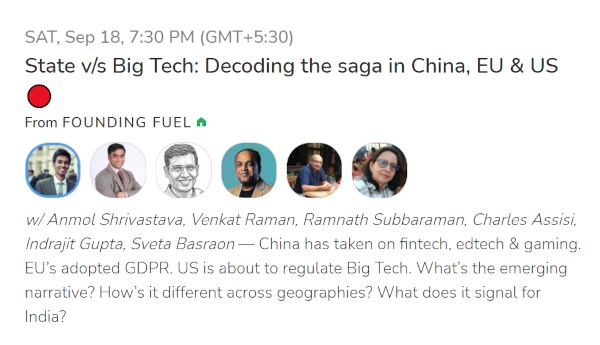

And join G Venkat Raman on Clubhouse for a chat on State Vs Big Tech: Decoding the saga in China, EU & US. Time: Saturday, September 18, 7.30 PM (IST)