[Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

From the earlier sections of the essay, it seems to be very evident that we are witnessing the emergence of a tipping point stemming from a consensus that the state needs to rein in Big Tech. I had discussed the various motivations for the state to regulate Big Tech players in the three major ecosystems of the US, the EU, and China. Irrespective of the nature of the political systems, regulation of technology companies seems to be inevitable. On some counts, the three major technology ecosystems are motivated by similar concerns like protecting individual privacy and checking cartelization of the tech industry. On some other grounds, they are found to have different compulsions to regulate Big Tech.

Let’s try to find the similarities related to tech regulation. Privacy protection and checking the monopolistic practices by Big Tech players to pre-empt competition are dominant concerns in the three regions. Notwithstanding these similarities, the unique ecosystems in each of the three areas have prioritized one or more than one area to regulate Big Tech and have motivated different degrees of regulation. For instance, there seems to be bipartisan support to regulate Big Tech to check its market abuses in the US. However, influential voices still contend that an overzealous regulatory ecosystem might handicap one of the greatest strengths in the form of a Silicon Valley, the hub of modern-day tech innovation. In the European region, apart from the EU, France, Germany, and Britain are keen to regulate Big Tech players from the US and China to encourage the growth of homegrown tech companies. The region wants to promote the competitive market as an end in itself and, under any circumstances, doesn’t want non-EU tech players to gobble up homegrown startups. As mentioned earlier, the historical experiences of Europe with Fascism and Nazism have led to very stringent privacy protection laws given the sentiments of the European society. In China, an authoritarian party-state finds it unacceptable that the local tech players are in any position to rival the state and therefore are keen to nip the potency of the influential tech players in the nascent stage itself.

Despite the popular narrative regarding globalization’s homogenizing tendencies, we still witness a complex world with various socio-economic, political, and cultural systems. These differences have complicated the job of the tech companies to cope with different approaches. In addition, the breakneck speed in which technology and innovation have advanced has left tech players very little time to brood over the dos and don’ts of their business.

Often, corporate greed has gotten the better of corporate needs due to an amorphous ecosystem that couldn't come up with timely legal mandates to regulate the tech industry. The absence of adequate legal regulations constraining the expansion of Big Tech has been compounded by the lack of any social sanction of Big Tech. It looks as if the freebies offered by the internet have hypnotized users who don’t mind compromising their privacy. Big Tech players have enjoyed the first movers’ advantage given the absence of any regulations and societal expectations.

Pro-tech regulators contend that the over-zealousness exhibited by American Big Tech players (Alphabet, Facebook, Amazon) and Chinese Big Tech players (Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu) to grow too fast too soon has compelled state regulation of this sector. On their part, the Big Tech players have been arguing that they are reaping the rewards of their hard-earned success. Since there has been no clarity in the legal guidelines, they are primarily unclear about their apparent wrongdoings. Moreover, sympathizers of Big Tech contend that an overzealous regulation will thwart the innovation of new products and services.

In recent times, there have been numerous commentaries on the domestic compulsions of the state to rein Big Tech. Still, not many have endeavoured to unravel the various geopolitical dimensions that have motivated China, the US, and the EU to regulate Big Tech. Before concluding the essay, where I try to look at implications of the State Vs Big Tech debate in the Indian context, I will highlight some of the geopolitical concerns that have motivated the tech regulation in the three different ecosystems.

The Geopolitics of Tech Regulation

The second decade of the twenty-first century has witnessed the emergence of a fresh wave of nationalism. Illusions about the internet making the world flat have given way to the reassertion of national interests. In 2017 Google opened an AI lab in Beijing, saying AI and its benefits have no borders, but in the Covid era, things have altered dramatically. Brexit, the America First or Make America Great Again (MAGA) campaigns in the US, and the China Dream in China, have coincided with what many experts call a Technomic war. This war has been inspired by the state’s determination to protect what is called ‘cyber sovereignty’ against the onslaught of tech players.

Why has the state felt compelled to do so? First, increasingly, commercial-origin technology has a bearing on national security considerations. For instance, Huawei’s 5G technology has widespread usage in the defense and other industries, causing alarms in the US administration. Second, technological advancements like AI and Big Data have increased the vulnerability of states due to fears of cyber-security breaches likely to be caused by adversaries in the form of state and non-state actors. Third, Big Tech players are increasingly spending vast amounts of money on R&D to maximize their commercial objectives. According to a Deloitte Centre for Government Insights Report, commercial companies were investing more than twice in R&D in 2016 compared to the government. This spending was in stark contrast to the 1960s when the government used to fund more than 50% of all research and development. Given that the private tech players are investing huge sums in R&D, they are more than likely to chase uncontrolled growth and seek more profits by reaching out to different markets across the globe. These geopolitical compulsions have motivated the state regulation of technology.

Big Tech became a significant source of the Technomic war between the US and China. These tensions have also led to the involvement of the EU. Each of these states had to contend with a particular set of new geopolitical realities. Not surprisingly, all the three states decided to take similar action, that is, assert greater control over the tech industry.

Geopolitical Tensions Spurring Tech Nationalism

In the past few years, among many other factors, two significant geopolitical factors caused tech nationalism to get special mention: a) the Sino-US Technomic War and b) the emergence of two distinct tech worlds. For lack of space, I will briefly examine these two critical factors causing state regulation of Big Tech, especially in the US and China.

The Sino-US Technomic War

The emergence of China as a tech power has led to what many are called the beginning of a tech war. The challenge posed by the Chinese state in the form of ‘authoritarian capitalism’ has forced former and current US officials to revisit the US model. The former Attorney General, William Barr, advocates that, like China, the US also needs to mobilize the state, business, and academia and decide on ‘which horse we will ride in this race.’ The US President Joe Biden was quoted saying, “Decades of neglect and disinvestment have left us at a competitive disadvantage as countries across the globe, like China, have poured money and focus into new technologies and industries, leaving us at real risk of being left behind.”

China baiters argue that while the Chinese state can pump a lot of money and force its players like Huawei to invest in R&D on 5G and other advanced technology, the US and EU cannot arm-twist their tech players to build low-margin 5G networks. The Chinese leadership has unequivocally announced its ambitions to become the numero uno in the tech domain. In the fifth plenum held in October 2020, the Communist Party of China’s Central Committee declared that China should “make breakthroughs in crucial core technologies, entering the front-ranking of innovative countries.” The Made in China 2025 plan, the 14th five-year plan, and the master plan 2035 indicate ‘DeAmericanizing’ China’s tech ecosystem. Expressing its fierce determination, one Chinese leader said that “China doesn’t want to replace the US but displace the US.”

One World, Two Systems

The tech rivalries among the major powers have caused a split in the digital estate, giving rise to two distinct spheres of influence. Reconfiguring global tech value chains, Sino-US tech decoupling motivated by the geopolitics of Big Data, 5G technology, have all but made the possibility of splinternet inevitable. With data being the core of AI, the US has been wary that Big Data will help China prepare dossiers of personal information for blackmailing and conducting political and corporate espionage. This factor was one of the concerns which led the Trump administration to impose bans on ByteDance’s TikTok and Tencent’s WeChat. Given such concerns, we are likely to witness the emergence of two separate ecosystems in the tech domain.

The two different political systems and different tech regimes will likely witness a race to set standards. In the 19th century, German industrialist and innovator Werner von Siemens quipped “He who owns the standards owns the market.” China and the US fiercely compete to shape, develop, and implement the tech domain’s global standards. In the era of Cold War 2.0, industry standards are becoming a significant area of contestation. In the recent past, standards-setting was an exclusive privilege of a few advanced countries, but today China is increasingly challenging this Western monopoly. China is increasing its influence in bodies like the International Electrotechnical Commission, and International Telecommunication Union (ITU). As of March 2019, China proposed 11 standards for IoT within the ISO/IEC (International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission) framework; five have already been adopted, with another six under review.

What Does the State Vs Big Tech Debate Mean for India?

This essay will be incomplete if we don’t use this opportunity to make sense of the recent developments that have taken place in India in the context of the State Vs Big Tech debate. The new IT Rules framed in Feb 2021 and made effective from May 2021 have added further impetus to this debate. Information and Communication Technology social media (ICT SM) like Google, Facebook, and WhatsApp must fulfill a specific legal mandate to operate in the Indian market. While some have protested, like WhatsApp and Twitter, others have grudgingly accepted the new regulatory environment. Given that India is a vast and lucrative market for these players, protesting beyond a point is not going to do any good to these companies. Consider the following. WhatsApp has the most extensive subscriber base in the world, and is likely to soon reach 500 million users in India. Facebook has 340 million, YouTube 425 million, Instagram 180 million, and Twitter has 22 million users in India. Given this kind of access to social media, what sense can we make of the implications of state regulation of Big Tech for the three major stakeholders, namely, policymakers (government), tech players (business), and society?

To begin with, we need to keep in mind the unique attributes of the Indian ecosystem before we examine the impact of tech regulation on the key stakeholders, namely, policymakers, tech companies, and the larger society comprising individuals. It is equally pertinent to note that the unique features of our society necessitate a regulatory regime befitting our national requirements. Unlike others, our society is characterized by socio-cultural heterogeneities. Second, despite affordable prices for telecom services and cheaper versions of smartphones, there is an evident digital divide. Third, given that we are a thickly populated country, the state in India is overstretched to execute law and order functions. How do these three things affect the regulatory environment?

First, India's cultural pluralism, its strength, has proved to be an ideal market for Big Tech social media companies. Some informed scholars opine that the growth of social media companies has led to a gradual demise of centrist leanings. Social media platforms have become an ideal breeding ground for fake news, propaganda, and divisive forces that polarize societies. Given the cultural heterogeneities coupled with the digital, certain sections of the society may manipulate public opinion for their narrow political objectives. Lack of awareness about how social media algorithms unfold, growing intolerance, and tendencies to take meaningless WhatsApp forwards can have a menacing effect in the form of communal clashes, inciting mob violence, and destabilizing social media order. Further, given that the state’s law and order machinery is overstretched to perform ordinary law and order functions, mob violence and communal clashes caused by misinformation campaigns and fake news can lead to significant social repercussions.

Such a situation is ideal for social media companies whose business model thrives on data harvests and prospers by offering its platforms. Pursuing a ‘game of profit’, they offer their platforms, allowing the dissemination of information/misinformation cheaply within seconds. If unchecked, social media platforms in their ruthless pursuits can act as the wrestling mat between the state and civil society.

The digital divide in the country further complicates the Indian situation. First, a few influential sections can manipulate people via social media platforms to engage in anti-social and anti-national activities in areas with a digital divide. For instance, it has been reported how Twitter became a handy tool in the hands of radical outfits in societies like Yemen and Syria. Of course, in certain societies where the internet infrastructure has been robust, Twitter has become a potent tool of political mobilization during the Arab Spring. Still, in a democratic society like India, it is difficult to see the brighter side of an unregulated tech environment. Recently on January 26, 2021, Republic Day, when a group of people was vandalizing the premises of the Red Fort in the name of farmers’ protest, Twitter was asked to pull down some handles inciting violence. Still, it refused, citing that it’s going to curb freedom of speech and expression. Mind you, it was the same Twitter that banned Donald Trump for specific Tweets from his handle.

In short, the weaponization of social media platforms fueled by affordable smartphones necessitates the regulation of Big Tech in India. Technologically, India is at par with Europe in understanding the nuances of algorithms on the basis of which social media functions, but we are yet to come to grips with the impact of algorithms based on a particular line of coding on the complexities of our society.

As far as policymakers are concerned, they must increasingly contend with the challenge of upholding national security interests with appropriate degrees of tech regulation without stifling the appetite of tech companies for innovation. Given the relative infancy of our local tech ecosystem compared to the US and China and a world infested with tech nationalism, it will be a major challenge to provide a conducive ecosystem that encourages innovation, leading to unique solutions to our unique problems. Regulators in the democratic world need to consider that the answer to the challenges posed by Big Tech can’t be found in the Chinese model of ‘authoritarian capitalism’ and look for solutions more conducive to their respective ecosystems.

Big Tech players need to understand the uniqueness of the Indian social and political system. Blind pursuit of profits might become ill-conceived goals leading to overvaluing outcomes and, in the process inviting more regulations and ending up becoming less competitive. Mark Zuckerberg’s enticement for Free Basics a few years back to become a gatekeeper is a case in point. Big Tech’s defiance of societal expectations and propensity to encash legal ambiguities has violated their unspoken social contract with society. Last, the industry has always prided itself on its innovative capacities without state interventions. The big question is can it deliver innovative products and services, despite the state?

In today's age, society also needs to pull up its socks. No amount of tech regulation by the state can protect individual privacy. The onus of protecting personal privacy is as much on the individual. As the Irish politician John Curran once said, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” While accessing the benefits of the internet, it is pertinent for users to be conscious of their digital footprints and the likely abuses it can be subjected to without their knowledge.

Further, Big Tech’s offerings are highly addictive. Blake Masters, president of Thiel Foundation, a private foundation, writing for The Wall Street Journal, called for resisting the “domination of corporate technocracy,” which via algorithmic bombarding instigates the dopamine in each of us, causing us to be slaves to our electronic gadgets. Calls to rein the Big Tech on this account have become shriller even in democratic US, which vouches for the sanctity of individual liberty. In China, the state has come hard on offerings by tech players by terming them as “spiritual opium”. The Covid era has deepened our reliance on social media for connecting with friends and relatives, for online education plus entertainment, food/grocery delivery, and a host of other things. The onus is on us not to become slaves to gadgets and become more aware of our right to privacy and ensure that our personal information doesn’t get monetized or vulnerable sections like women and children don’t get victimized.

Finally, the biggest question from the societal perspective is, will the state be adding new armory with new forms of e-governance? Technology-aided tools will further enable the state to snoop on individuals. This threat has been present in authoritarian China and in the US, leading to one of the most widely discussed cases of whistleblowing, the Edward Snowden controversy. So, the bigger question is, who is going to bell the big cat called state?

Editor’s Note

Read Parts 1-3 of this series on State Vs Big Tech:

- Part 1 on the techlash in China

- Part 2 on the drivers for regulation in the EU

- And Part 3 on taming the American giants

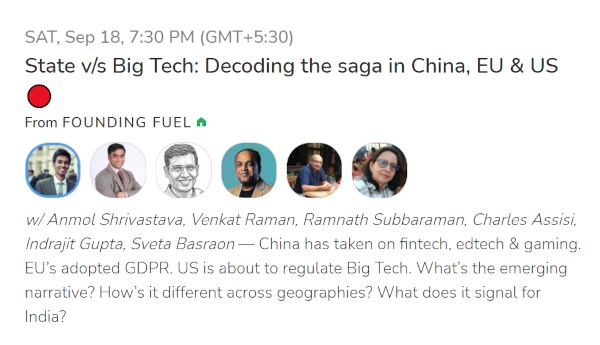

Join G Venkat Raman on Clubhouse for a chat on State Vs Big Tech: Decoding the saga in China, EU & US. Time: Saturday, September 18, 7.30 PM (IST)